South Sudan's Renewable Energy Potential

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNMISS “Protection of Civilians” (Poc) Sites

UNMISS “Protection of Civilians” (PoC) Sites As of 9 April, the estimated number of civilians seeking safety in six Protection of Civilians (PoC) sites located on UNMISS bases is 117,604 including 52,908 in Bentiu, 34,420 in Juba UN House, 26,596 in Malakal, 2,374 in Bor, 944 in Melut and 362 in Wau. Number of civilians seeking protection STATE LOCATION Central UN House PoC I, II and III 34,420 Equatoria Juba Jonglei Bor 2,374 Upper Nile Malakal 26,596 Melut 944 Unity Bentiu 52,908 Western Bahr Wau 362 El Ghazal TOTAL 117,604 Activities in Protection Sites Juba, UN House The refugee agency in collaboration with the South Sudanese Commission for Refugee Affairs will be looking into issuing Asylum seeker certificates to around 500 foreign nationals at UN House PoC Site from 9 to 15 April. ADDITIONAL LINKS CLICK THE LINKS WEBSITE UNMISS accommodating 4,500 new IDPS in Malakal http://bit.ly/1JD4C4E Children immunized against measles in Bentiu http://bit.ly/1O63Ain Education needs peace, UNICEF Ambassador says in Yambio http://bit.ly/1CH51wX Food coming through Sudan helping hundreds of thousands http://bit.ly/1FBHHmw PHOTO UN Photo http://www.unmultimedia.org/s/photo/detail/627/0627829.html http://www.unmultimedia.org/s/photo/detail/627/0627828.html http://www.unmultimedia.org/s/photo/detail/627/0627831.html UNMISS facebook albums: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.817801171628889.1073742395.160839527325060&type=3 https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.818162894926050.1073742396.160839527325060&type=3 UNMISS flickr album: -

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE to SOUTH SUDAN Last Updated 07/31/13

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO SOUTH SUDAN Last Updated 07/31/13 UPPER NILE SUDAN WARRAP ACTED Solidarités ACTED CRS World ABYEI AREA Renk Vision GOAL Food for SOUTH SUDAN CRS SC the Hungry ACTED MENTOR UNITY FAO UNDP GOAL DRC NRC CARE Global Communities/CHF UNFPA Medair IOM UNOPS Mercy Corps GOAL UNICEF MENTOR RI WCDO MENTOR Mercy Corps UNMAS RI World IOM Paloich OCHA WHO Vision SouthSouth Sudan-SudanSudan-Sudan boundaryboundary representsrepresents JanuaryJanuary 1,1, 19561956 alignment;alignment; finalfinal alignmentalignment pendingpending ABYEI AREA * UPPER NILE negotiationsnegotiations andand demarcation.demarcation. Abyei ETHIOPIA Malakal Abanima SOUTH SUDAN-WIDE Bentiu Nagdiar Warawar JONGLEI FAO Agok Yargot ACTED IOM WESTERN BAHR Malualkon NORTHERN UNITY EL GHAZAL Aweil Khorflus Nasir CRS Medair BAHR Pagak WARRAP Food for OCHA Raja EL GHAZAL the Hungry UNICEF Fathay Walgak BAHR EL GHAZAL IMC Akobo WFP Adeso MENTOR Wau WHO Tearfund PACT SOUTH SUDAN JONGLEI UNICEF UMCOR Pochalla World WFP Vision Welthungerhilfe Rumbek ICRC LAKES UNHCR CENTRAL Wulu Mapuordit AFRICAN Akot Bor Domoloto Minkamman REPUBLIC PROGRAM KEY Tambura Amadi USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP State/PRM Kaltok WESTERN EQUATORIA EASTERN EQUATORIA Agriculture and Food Security Livelihoods Juba Kapoeta Economic Recovery and Market Logistics and Relief Commodities Systems Yambio Multi-Sectoral Assistance CENTRAL Education EQUATORIA Torit Nagishot Nutrition EQUATORIA Gender-based Birisi ARC Violence Prevention Protection Ye i CHF Health Risk Management Policy and Practice KENYA -

EOI Mission Template

United Nations Nations Unies United Nation Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) South Sudan REQUEST FOR EXPRESSION OF INTEREST (EOI) This notice is placed on behalf of UNMISS. United Nations Procurement Division (UNPD) cannot provide any warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of contents of furnished information; and is unable to answer any enquiries regarding this EOI. You are therefore requested to direct all your queries to United Nation Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) using the fax number or e-mail address provided below. Title of the EOI: Provision of Refrigerant Gases to UNMISS in Juba, Bor, Bentiu, Malakal, Wau, Kuajok, Rumbek, Aweil, Torit and Yambio, Republic of South Sudan Date of this EOI: 10 January 2020 Closing Date for Receipt of EOI: 11 February 2020 EOI Number: EOIUNMISS17098 Chief Procurement Officer Unmiss Hq, Tomping Site Near Juba Address EOI response by fax or e-mail to the Attention of: International Airport, Room No 3c/02 Juba, Republic Of South Sudan Fax Number: N/A E-mail Address: [email protected], [email protected] UNSPSC Code: 24131513 DESCRIPTION OF REQUIREMENTS PD/EOI/MISSION v2018-01 1. The United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS) has a requirement for the provision of Refrigerant Gases in Juba, Bor, Bentiu, Malakal, Wau, Kuajok, Rumbek, Aweil, Torit and Yambio, Republic of South Sudan and hereby solicits Expression of Interest (EOI) from qualified and interested vendors. SPECIFIC REQUIREMENTS / INFORMATION (IF ANY) Conditions: 2. Interested service providers/companies are invited to submit their EOIs for consideration by email (preferred), courier or by hand delivery as indicated below. -

Promoting Peace and Resilience in Unity State, South Sudan

BRIEF / FEBRUARY 2021 Promoting peace and resilience in Unity state, South Sudan The town of Bentiu, located in Rubkona County, is the comprising 11,529 households.1 Although people capital of the oil-rich Unity state and is predominately living in the PoC site are provided with protection and inhabited by the Nuer people. A series of waterways and humanitarian assistance, they still face challenges swamps cover large parts of the state and these provide including economic hardship, being targeted by armed pasture in the dry season for animals belonging to Nuer groups, violent crime, revenge killings inside the PoC and Dinka pastoralists, as well as other pastoralist site, and outbreaks of disease as a result of the crowded groups from neighbouring Sudan who migrate with conditions in which they live. In July 2020, UNMISS their animals into South Sudan during dry seasons in initiated consultations about its intention to re-designate search of grazing land and water. Unity state also sits the PoC sites in the country to IDP camps and hand over on some of the largest oil deposits in South Sudan and a responsibility of these camps to the government of South considerable amount of petroleum-related activity takes Sudan. People living in the Bentiu PoC site expressed place in and around Bentiu. The production of oil has concern at this plan – while conditions inside the contributed to fuelling conflicts in the state, resulting in camp are very poor, IDPs fear the threat of violence and displacement and environmental degradation. insecurity outside the PoCs if responsibility is transferred. -

Taming the Intractable Inter-Ethnic Conflict in the Ilemi Triangle

International Journal of Innovative Research and Knowledge Volume-3 Issue-7, July-2018 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE ISSN-2213-1356 www.ijirk.com TAMING THE INTRACTABLE INTER-ETHNIC CONFLICT IN THE ILEMI TRIANGLE PETERLINUS OUMA ODOTE, PHD Abstract This article provides an overview of the historical trends of conflict in the Ilemi triangle, exploring the issues, the nature, context and dynamics of these conflicts. The author endeavours to deepen the understanding of the trends of conflict. A consideration on the discourse on the historical development is given attention. The article’s core is conflict between the five ethnic communities that straddle this disputed triangle namely: the Didinga and Toposa from South Sudan; the Nyangatom, who move around South Sudan and Ethiopia; the Dassenach, who have settled East of the Triangle in Ethiopia; and the Turkana in Kenya. The article delineates different factors that promote conflict in this triangle and how these have impacted on pastoralism as a way of livelihood for the five communities. Lastly, the article discusses the possible ways to deal with the intractable conflict in the Ilemi Triangle. Introduction Ilemi triangle is an arid hilly terrain bordering Kenya, South Sudan and Ethiopia, that has hit the headlines and catapulted onto the international centre stage for the wrong reasons in the recent past. Retrospectively, the three countries have been harshly criticized for failure to contain conflict among ethnic communities that straddle this contested area. Perhaps there is no better place that depicts the opinion that the strong do what they will and the weak suffer what they must than the Ilemi does. -

Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014

IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Initial Rapid Needs Assessment: Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014 This IRNA Report is a product of Inter-Agency Assessment mission conducted and information compiled based on the inputs provided by partners on the ground including; government authorities, affected communities/IDPs and agencies. 0 IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Situation Overview: An ad-hoc IDP camp has been established by the Melut County Commissioner at Dethoma in order to accommodate Dinka IDPs who have fled from Baliet county. Reports of up to 45,000 based in Paloich were initially received by OCHA from RRC and UNMISS staff based in Melut but then subsequent information was received that they had moved to Dethoma. An IRNA mission from Malakal was conducted on 31 January 2014. Due to delays in the deployment by helicopter, the RRC Coordinator was unable to meet the team but we were able to speak to the Deputy Paramount Chief, Chief and a ROSS NGO at the site. The local NGO (Woman Empowerment for Cooperation and Development) had said they had conducted a preliminary registration that showed the presence of 3,075 households. The community leaders said that the camp contained approximately 26,000 individuals. The IRNA team could only visually estimate 5 – 6000 potentially displaced however some may have been absent at the river. The camp is situated on an open field provided and cleared by the Melut County Commissioner, with a river approximately 300metres to the south. There is no cover and as most IDPs had walked to this location, they had carried very minimal NFIs or food. -

Sudan a Country Study.Pdf

A Country Study: Sudan An Nilain Mosque, at the site of the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Helen Chapin Metz Research Completed June 1991 Table of Contents Foreword Acknowledgements Preface Country Profile Country Geography Society Economy Transportation Government and Politics National Security Introduction Chapter 1 - Historical Setting (Thomas Ofcansky) Early History Cush Meroe Christian Nubia The Coming of Islam The Arabs The Decline of Christian Nubia The Rule of the Kashif The Funj The Fur The Turkiyah, 1821-85 The Mahdiyah, 1884-98 The Khalifa Reconquest of Sudan The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1899-1955 Britain's Southern Policy Rise of Sudanese Nationalism The Road to Independence The South and the Unity of Sudan Independent Sudan The Politics of Independence The Abbud Military Government, 1958-64 Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69 The Nimeiri Era, 1969-85 Revolutionary Command Council The Southern Problem Political Developments National Reconciliation The Transitional Military Council Sadiq Al Mahdi and Coalition Governments Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment (Robert O. Collins) Physical Setting Geographical Regions Soils Hydrology Climate Population Ethnicity Language Ethnic Groups The Muslim Peoples Non-Muslim Peoples Migration Regionalism and Ethnicity The Social Order Northern Arabized Communities Southern Communities Urban and National Elites Women and the Family Religious -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM Via Free Access “They Are Now Community Police” 411

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 410-434 brill.com/ijgr “They Are Now Community Police”: Negotiating the Boundaries and Nature of the Government in South Sudan through the Identity of Militarised Cattle-keepers Naomi Pendle PhD Candidate, London School of Economics, London, UK [email protected] Abstract Armed, cattle-herding men in Africa are often assumed to be at a relational and spatial distance from the ‘legitimate’ armed forces of the government. The vision constructed of the South Sudanese government in 2005 by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement removed legitimacy from non-government armed groups including localised, armed, defence forces that protected communities and cattle. Yet, militarised cattle-herding men of South Sudan have had various relationships with the governing Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement/Army over the last thirty years, blurring the government – non government boundary. With tens of thousands killed since December 2013 in South Sudan, questions are being asked about options for justice especially for governing elites. A contextual understanding of the armed forces and their relationship to gov- ernment over time is needed to understand the genesis and apparent legitimacy of this violence. Keywords South Sudan – policing – vigilantism – transitional justice – war crimes – security © NAOMI PENDLE, 2015 | doi 10.1163/15718115-02203006 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 (CC-BY-NC 4.0) License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM via free access “they Are Now Community Police” 411 1 Introduction1 On 15 December 2013, violence erupted in Juba, South Sudan among Nuer sol- diers of the Presidential Guard. -

Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the Market of Mayen Rual South Sudan Customary Authorities Project

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT WARTIME TRADE AND THE RESHAPING OF POWER IN SOUTH SUDAN LEARNING FROM THE MARKET OF MAYEN RUAL SOUTH SUDAN customary authorities pROjECT Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the market of Mayen Rual NAOMI PENDLE AND CHirrilo MADUT ANEI Published in 2018 by the Rift Valley Institute PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya 107 Belgravia Workshops, 159/163 Marlborough Road, London N19 4NF, United Kingdom THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. THE AUTHORS Naomi Pendle is a Research Fellow in the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa, London School of Economics. Chirrilo Madut Anei is a graduate of the University of Bahr el Ghazal and is an emerging South Sudanese researcher. SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT RVI’s South Sudan Customary Authorities Project seeks to deepen the understand- ing of the changing role of chiefs and traditional authorities in South Sudan. The SSCA Project is supported by the Swiss Government. CREDITS RVI EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mark Bradbury RVI ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATIONS: Cedric Barnes RVI SOUTH SUDAN PROGRAMME MANAGER: Anna Rowett RVI SENIOR PUBLICATIONS AND PROGRAMME MANAGER: Magnus Taylor EDITOR: Kate McGuinness DESIGN: Lindsay Nash MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-56-2 COVER: Chief Morris Ngor RIGHTS Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2018 Cover image © Silvano Yokwe Alison Text and maps published under Creative Commons License Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available for free download from www.riftvalley.net Printed copies are available from Amazon and other online retailers. -

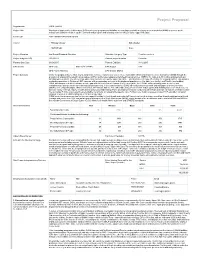

Project Proposal

Project Proposal Organization GOAL (GOAL) Project Title Provision of treatment to children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women diagnosed with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) or severe acute malnutrition (SAM) for children aged 659 month and pregnant and lactating women in Melut County, Upper Nile State Fund Code SSD15/HSS10/SA2/N/INGO/526 Cluster Primary cluster Sub cluster NUTRITION None Project Allocation 2nd Round Standard Allocation Allocation Category Type Frontline services Project budget in US$ 150,000.01 Planned project duration 5 months Planned Start Date 01/08/2015 Planned End Date 31/12/2015 OPS Details OPS Code SSD15/H/73049/R OPS Budget 0.00 OPS Project Ranking OPS Gender Marker Project Summary Under the proposed intervention, GOAL will provide curative responses to severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) through the provision of outpatient therapeutic programmes (OTPs) and targeted supplementary feeding programmes (TSFPs) for children 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW). The intervention will be targeted to Melut County, Upper Nile State – which has been heavily affected by the ongoing conflict. This includes continuing operations in Dethoma II IDP camp as well as expanding services to the displaced populations in Kor Adar (one facility) and Paloich (two facilities). GOAL also proposes to fill the nutrition service gap in Melut Protection of Civilians (PoC) camp. In the PoC, GOAL will be providing static services, with complementary primary health care and nutrition programming. In the same locations, GOAL will conduct mass outreach and mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening campaigns within communities, IDP camps, and the PoC with children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW) in order to increase facility referrals. -

Figure 1. Southern Sudan's Protected Areas

United Nations Development Programme Country: Sudan PROJECT DOCUMENT Launching Protected Area Network Management and Building Capacity in Post-conflict Project Title: Southern Sudan By end of 2012, poverty especially among vulnerable groups is reduced and equitable UNDAF economic growth is increased through improvements in livelihoods, food security, decent Outcome(s): employment opportunities, sustainable natural resource management and self reliance; UNDP Strategic Plan Environment and Sustainable Development Primary Outcome: Catalyzing access to environmental finance UNDP Strategic Plan Secondary Outcome: Mainstreaming environment and energy Expected CP Outcome(s): Strengthened capacity of national, sub-national, state and local institutions and communities to manage the environment and natural disasters to reduce conflict over natural resources Expected CPAP Output(s) 1. National and sub-national, state and local institutions and communities capacities for effective environmental governance, natural resources management, conflict and disaster risk reduction enhanced. 2. Comprehensive strategic frameworks developed at national and sub-national levels regarding environment and natural resource management Executing Entity/Implementing Partner: NGO Execution Modality – WCS in cooperation with the Ministry of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism of the Government of Southern Sudan (MWCT-GoSS) Implementing Entity/Responsible Partners: United Nations Development Programme Brief Description The current situation Despite the 1983 to 2005 civil war, many areas of Southern Sudan still contain areas of globally significant habitats and wildlife populations. For example, Southern Sudan contains one of the largest untouched savannah and woodland ecosystems remaining in Africa as well as the Sudd, the largest wetland in Africa, of inestimable value to the flow of the River Nile, the protection of endemic species and support of local livelihoods. -

2.2 South Sudan Aviation

2.2 South Sudan Aviation Key airport information may also be found at World Aero Data. Civil aviation falls under the authority of the Ministry of Transport and South Sudan which has been a member of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) since 10 November 2011. In 2013, the South Sudan Civil Aviation Authority was established and the aim of this statutory authority is to formally oversee and regulate the countries aviation industry, airline companies, and operations. South Sudan’s Juba International Airport (JIA) is currently the only airport receiving flights from international commercial airline carriers. The other major airports include Wau, Malakal and Rumbek. The aviation industry in general is characterized by decades of underdevelopment, little investment in infrastructure, low capacity and a poor safety record and adherence to international standards. The country is however readily accessible by air as there are hundreds of fixed wing and helicopter landing sites spread out across the country, of which more than 50 airstrips are serviceable by fixed wing aircraft. The vast majority of these strips are gravel however and only accessible by light aircraft. Only Juba, Paloich, Malakal and Wau airports currently have asphalted runways capable of handling large aircraft. The availability of fuel, aircraft maintenance facilities and handling services remains an issue, especially in remote areas. A small number of private sector operators are able to supply fuel at the various major airports, however fuel is imported from neighboring countries increasing cost and risking fuel shortages, especially during the rainy season. Basic repairs and maintenance can be conducted in South Sudan; however, major repairs have to be conducted in neighboring countries or in some cases Europe.