Livelihoods Zone Map and Descriptions for South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Western Equatoria Infographic V6 Final

Joint report by United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) and Ofce of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Report on violations and abuses against civilians in Gbudue April–August and Tambura States, Western Equatoria 2018 INTRODUCTION This report is jointly published by the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) and the Ofce of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), pursuant to United Nations Security Council resolution 2406 (2018). The report presents the ndings of an investigation conducted by the UNMISS Human Rights Division (UNMISS HRD) into violations and abuses of international human rights law and violations of international humanitarian law reportedly committed by the pro-Machar Sudan People’s Liberation Army in Opposition (SPLA-IO (RM)) and the Government’s Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) against civilians in the states of Gbudue and Tambura, in Western Equatoria, between April and August 2018. The report documents the plight of civilians in the Western Equatoria region of South Sudan, where increased violence and attacks between April and August 2018 saw nearly 900 people abducted, including 505 women, and forced into sexual slavery or combat, and over 24,000 displaced from their homes. The report identies three SPLA-IO commanders who may bear the greatest responsibility for the violence committed against the civilian population in Western Equatoria during the period under consideration. HRD employed the standard of proof of reasonable grounds to believe in making factual determinations about the violations and abuses incidents, and patterns of conduct of the perpetrators. Unless specically stated, all information in the report has been veried using several independent, credible and reliable sources, in accordance with OHCHR’s human rights monitoring and investigation methodology. -

Republic of South Sudan "Establishment Order

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN "ESTABLISHMENT ORDER NUMBER 36/2015 FOR THE CREATION OF 28 STATES" IN THE DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Order 1 Preliminary Citation, commencement and interpretation 1. This order shall be cited as "the Establishment Order number 36/2015 AD" for the creation of new South Sudan states. 2. The Establishment Order shall come into force in thirty (30) working days from the date of signature by the President of the Republic. 3. Interpretation as per this Order: 3.1. "Establishment Order", means this Republican Order number 36/2015 AD under which the states of South Sudan are created. 3.2. "President" means the President of the Republic of South Sudan 3.3. "States" means the 28 states in the decentralized South Sudan as per the attached Map herewith which are established by this Order. 3.4. "Governor" means a governor of a state, for the time being, who shall be appointed by the President of the Republic until the permanent constitution is promulgated and elections are conducted. 3.5. "State constitution", means constitution of each state promulgated by an appointed state legislative assembly which shall conform to the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan 2011, amended 2015 until the permanent Constitution is promulgated under which the state constitutions shall conform to. 3.6. "State Legislative Assembly", means a legislative body, which for the time being, shall be appointed by the President and the same shall constitute itself into transitional state legislative assembly in the first sitting presided over by the most eldest person amongst the members and elect its speaker and deputy speaker among its members. -

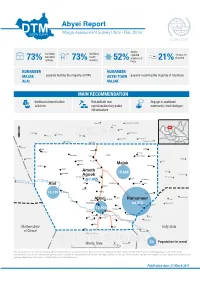

20170331 Abyei

Abyei Report Village Assessment Survey | Nov - Dec 2016 IOM OIM bomas functional functional reported villages are 73% education 73% health 52% presence of 21% deserted facilities facilities UXOs. RUMAMEER RUMAMEER MAJAK payams hosting the majority of IDPs ABYEI TOWN payams receiving the majority of returnees ALAL MAJAK MAIN SURVEY RECOMMENDATIONS MAIN RECOMMENDATION livelihood diversication Rehabilitate and Engage in sustained activities operationalize key public community-level dialogue infrastructure Ed Dibeikir Ramthil Raqabat Rumaylah Nyam Roba Nabek Umm Biura El Amma Mekeines Zerafat SUDABeida N Ed Dabkir Shagawah Duhul Kawak Al Agad Al Aza Meiram Tajiel Dabib Farouk Debab Pariang Um Khaer Langar Di@ra Raqaba Kokai Es Saart El Halluf Pagol Bioknom Pandal Ajaj Kajjam Majak Ghabush En Nimr Shigei Di@ra Ameth Nyak Kolading 15,685 Gumriak 2 Aguok Goli Ed Dahlob En Neggu Fagai 1,055 Dumboloya Nugar As Sumayh Alal Alal Um Khariet Bedheni Baar Todach Saheib Et Timsah Noong 13,130 Ed Derangis Tejalei Feid El Kok Dungoup Padit DokurAbyeia Rumameer Todyop Madingthon 68,372 Abu Qurun Thurpader Hamir Leu 12,900 Awoluum Agany Toak Banton Athony Marial Achak Galadu Arik Athony Grinঞ Agach Awal Aweragor Madul Northern Bahr Agok Unity State Lort Dal el Ghazal Abiemnom Baralil Marsh XX Population in need SOUTH SUDANMolbang Warrap State Ajakuao 0 25 50 km The boundaries on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the Government of the Republic of South Sudan or IOM. This map is for planning purposes only. IOM cannot guarantee this map is error free and therefore accepts no liability for consequential and indirect damages arising from its use. -

The Criminalization of South Sudan's Gold Sector

The Criminalization of South Sudan’s Gold Sector Kleptocratic Networks and the Gold Trade in Kapoeta By the Enough Project April 2020* A Precious Resource in an Arid Land Within the area historically known as the state of Eastern Equatoria, Kapoeta is a semi-arid rangeland of clay soil dotted with short, thorny shrubs and other vegetation.1 Precious resources lie below this desolate landscape. Eastern Equatoria, along with the region historically known as Central Equatoria, contains some of the most important and best-known sites for artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASM). Some estimates put the number of miners at 60,000 working at 80 different locations in the area, including Nanaknak, Lauro (Didinga Hills), Napotpot, and Namurnyang. Locals primarily use traditional mining techniques, panning for gold from seasonal streams in various villages. The work provides miners’ families resources to support their basic needs.2 Kapoeta’s increasingly coveted gold resources are being smuggled across the border into Kenya with the active complicity of local and national governments. This smuggling network, which involves international mining interests, has contributed to increased militarization.3 Armed actors and corrupt networks are fueling low-intensity conflicts over land, particularly over the ownership of mining sites, and causing the militarization of gold mining in the area. Poor oversight and conflicts over the control of resources between the Kapoeta government and the national government in Juba enrich opportunistic actors both inside and outside South Sudan. Inefficient regulation and poor gold outflows have helped make ASM an ideal target for capture by those who seek to finance armed groups, perpetrate violence, exploit mining communities, and exacerbate divisions. -

WAR and PROTECTED AREAS AREAS and PROTECTED WAR Vol 14 No 1 Vol 14 Protected Areas Programme Areas Protected

Protected Areas Programme Protected Areas Programme Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 Parks Protected Areas Programme © 2004 IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 ISSN: 0960-233X Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS CONTENTS Editorial JEFFREY A. MCNEELY 1 Parks in the crossfire: strategies for effective conservation in areas of armed conflict JUDY OGLETHORPE, JAMES SHAMBAUGH AND REBECCA KORMOS 2 Supporting protected areas in a time of political turmoil: the case of World Heritage 2004 Sites in the Democratic Republic of Congo GUY DEBONNET AND KES HILLMAN-SMITH 9 Status of the Comoé National Park, Côte d’Ivoire and the effects of war FRAUKE FISCHER 17 Recovering from conflict: the case of Dinder and other national parks in Sudan WOUTER VAN HOVEN AND MUTASIM BASHIR NIMIR 26 Threats to Nepal’s protected areas PRALAD YONZON 35 Tayrona National Park, Colombia: international support for conflict resolution through tourism JENS BRÜGGEMANN AND EDGAR EMILIO RODRÍGUEZ 40 Establishing a transboundary peace park in the demilitarized zone on the Kuwaiti/Iraqi borders FOZIA ALSDIRAWI AND MUNA FARAJ 48 Résumés/Resumenes 56 Subscription/advertising details inside back cover Protected Areas Programme Vol 14 No 1 WAR AND PROTECTED AREAS 2004 ■ Each issue of Parks addresses a particular theme, in 2004 these are: Vol 14 No 1: War and protected areas Vol 14 No 2: Durban World Parks Congress Vol 14 No 3: Global change and protected areas ■ Parks is the leading global forum for information on issues relating to protected area establishment and management ■ Parks puts protected areas at the forefront of contemporary environmental issues, such as biodiversity conservation and ecologically The international journal for protected area managers sustainable development ISSN: 0960-233X Published three times a year by the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) of IUCN – Subscribing to Parks The World Conservation Union. -

Figure 1. Southern Sudan's Protected Areas

United Nations Development Programme Country: Sudan PROJECT DOCUMENT Launching Protected Area Network Management and Building Capacity in Post-conflict Project Title: Southern Sudan By end of 2012, poverty especially among vulnerable groups is reduced and equitable UNDAF economic growth is increased through improvements in livelihoods, food security, decent Outcome(s): employment opportunities, sustainable natural resource management and self reliance; UNDP Strategic Plan Environment and Sustainable Development Primary Outcome: Catalyzing access to environmental finance UNDP Strategic Plan Secondary Outcome: Mainstreaming environment and energy Expected CP Outcome(s): Strengthened capacity of national, sub-national, state and local institutions and communities to manage the environment and natural disasters to reduce conflict over natural resources Expected CPAP Output(s) 1. National and sub-national, state and local institutions and communities capacities for effective environmental governance, natural resources management, conflict and disaster risk reduction enhanced. 2. Comprehensive strategic frameworks developed at national and sub-national levels regarding environment and natural resource management Executing Entity/Implementing Partner: NGO Execution Modality – WCS in cooperation with the Ministry of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism of the Government of Southern Sudan (MWCT-GoSS) Implementing Entity/Responsible Partners: United Nations Development Programme Brief Description The current situation Despite the 1983 to 2005 civil war, many areas of Southern Sudan still contain areas of globally significant habitats and wildlife populations. For example, Southern Sudan contains one of the largest untouched savannah and woodland ecosystems remaining in Africa as well as the Sudd, the largest wetland in Africa, of inestimable value to the flow of the River Nile, the protection of endemic species and support of local livelihoods. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

The Role of Indigenous Languages in Southern Sudan: Educational Language Policy and Planning

The Role of Indigenous Languages in Southern Sudan: Educational Language Policy and Planning H. Wani Rondyang A thesis submitted to the Institute of Education, University of London, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2007 Abstract This thesis aims to questions the language policy of Sudan's central government since independence in 1956. An investigation of the root causes of educational problems, which are seemingly linked to the current language policy, is examined throughout the thesis from Chapter 1 through 9. In specific terms, Chapter 1 foregrounds the discussion of the methods and methodology for this research purposely because the study is based, among other things, on the analysis of historical documents pertaining to events and processes of sociolinguistic significance for this study. The factors and sociolinguistic conditions behind the central government's Arabicisation policy which discourages multilingual development, relate the historical analysis in Chapter 3 to the actual language situation in the country described in Chapter 4. However, both chapters are viewed in the context of theoretical understanding of language situation within multilingualism in Chapter 2. The thesis argues that an accommodating language policy would accord a role for the indigenous Sudanese languages. By extension, it would encourage the development and promotion of those languages and cultures in an essentially linguistically and culturally diverse and multilingual country. Recommendations for such an alternative educational language policy are based on the historical and sociolinguistic findings in chapters 3 and 4 as well as in the subsequent discussions on language policy and planning proper in Chapters 5, where theoretical frameworks for examining such issues are explained, and Chapters 6 through 8, where Sudan's post-independence language policy is discussed. -

Country Profile – Ethiopia

Country profile – Ethiopia Version 2016 Recommended citation: FAO. 2016. AQUASTAT Country Profile – Ethiopia. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licencerequest or addressed to [email protected]. FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/ publications) and can be purchased through [email protected]. -

Linkages-Success-Stories-South-Sudan

JULY 2016 SUCCESS STORY Success on Several Levels in South Sudan In South Sudan, obtaining HIV care and treatment is difficult for people living with HIV. Only 10 percent of those eligible are currently enrolled on antiretroviral therapy (ART). But for one key population — female sex workers (FSWs) — the barriers to comprehensive HIV care and treatment are particularly daunting. Many sex workers cannot afford to lose income while waiting for services at overburdened hospitals. And those who do seek care often find providers are reluctant to serve them because of the stigma associated with sex work. Recruiting and retaining FSWs and other key populations (KPs) into the HIV cascade of services is a complex issue that demands a response at many levels. In South Sudan, LINKAGES is helping to generate a demand for services, improve access to KP-friendly services, and create a policy environment that is more conducive to the health rights of key populations. GENERATING DEMAND FOR SERVICES The justified mistrust that FSWs have for the health care system keeps many from seeking the services they need. Peer education and outreach is a critical component of engaging KPs in the HIV cascade. LINKAGES South Sudan conducted a mapping exercise to identify hotspots (or key locations) where sex work takes place. From these locations, 65 FSWs were identified and trained as peer educators to lead participatory education sessions among their peers. The sessions are designed to motivate FSWs to adopt healthy behaviors and develop the skills to do so. The sessions cover topics like condom use, regular screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), periodic testing for HIV, and enrollment into care and treatment services for those living with HIV. -

Magwi County

Resettlement, Resource Conflicts, Livelihood Revival and Reintegration in South Sudan A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County by N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Department of International Environment and Development No. Report Noragric Studies 5 8 RESETTLEMENT, RESOURCE CONFLICTS, LIVELIHOOD REVIVAL AND REINTEGRATION IN SOUTH SUDAN A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County By N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Report No. 58 December 2010 Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences, UMB Noragric is the Department of International Environment and Development Studies at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB). Noragric’s activities include research, education and assignments, focusing particularly, but not exclusively, on developing countries and countries with economies in transition. Noragric Reports present findings from various studies and assignments, including programme appraisals and evaluations. This Noragric Report was commissioned by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) under the framework agreement with UMB which is administrated by Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the employer of the assignment (Norad) and with the consultant team leader (Noragric). The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this publication are entirely those of the authors and cannot be attributed directly to the Department of International Environment and Development Studies (UMB/Noragric). Shanmugaratnam, N. Resettlement, resource conflicts, livelihood revival and reintegration in South Sudan: A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County. Noragric Report No. 58 (December 2010) Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB) P.O. -

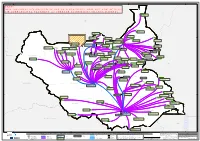

Note: This Information Should Be Use As a Reference and Not for Actual Air Operational Planning As Surface Conditions Change

24°0'E 28°0'E 32°0'E 36°0'E N O T E : e l i N e t i h T H I S I N F O R M A T I O N S H O U L D B E U S E A S A R E F E R E N C E A N D N O T F O R A C T U A L W A I R O P E R A T I O N A L P L A N N I N G A S S U R F A C E C O N D I T I O N S C H A N G E R A P I D L Y . Renk RWY Heading: 01/19 RWY Dimension: 15 x 1,500 Surface: Murram O v e r f l o w C h a n Sudan n e l R . B i bb an e il N e it h R W . S a n g e i r R . el- Sam aa R . W e h f Paloich e t RWY Heading: 01/19 RWY Dimension: 30 x 3,000 Surface: Tarmack RWY Heading: 13/31 R . R A RWY Dimension: 50 x 900 . h Y m a a Surface: Compacted murram le r Yida RWY Heading: 06/24 R . T om RWY Dimension: 34 x 800 b Ajuong Thok ak Maban 10°0'N Surface: Black cotton 10°0'N ) RWY Heading: 15/33 b a Pariang r RWY Heading: 14/32 A RWY Dimension: 25 x 1,300 l- Oriny e r RWY Dimension: 50 x 900 h Surface: Hard ground a Upper Nile (B Surface: Murram RWY Heading: 06/24 R ir .