Columbium and Tantalum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utopian Promise

Unit 3 UTOPIAN PROMISE Puritan and Quaker Utopian Visions 1620–1750 Authors and Works spiritual decline while at the same time reaffirming the community’s identity and promise? Featured in the Video: I How did the Puritans use typology to under- John Winthrop, “A Model of Christian Charity” (ser- stand and justify their experiences in the world? mon) and The Journal of John Winthrop (journal) I How did the image of America as a “vast and Mary Rowlandson, A Narrative of the Captivity and unpeopled country” shape European immigrants’ Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (captivity attitudes and ideals? How did they deal with the fact narrative) that millions of Native Americans already inhabited William Penn, “Letter to the Lenni Lenapi Chiefs” the land that they had come over to claim? (letter) I How did the Puritans’ sense that they were liv- ing in the “end time” impact their culture? Why is Discussed in This Unit: apocalyptic imagery so prevalent in Puritan iconog- William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation (history) raphy and literature? Thomas Morton, New English Canaan (satire) I What is plain style? What values and beliefs Anne Bradstreet, poems influenced the development of this mode of expres- Edward Taylor, poems sion? Sarah Kemble Knight, The Private Journal of a I Why has the jeremiad remained a central com- Journey from Boston to New York (travel narra- ponent of the rhetoric of American public life? tive) I How do Puritan and Quaker texts work to form John Woolman, The Journal of John Woolman (jour- enduring myths about America’s -

Determination of D003 by Capillary Gas Chromatography

Rev. CENIC Cienc. Quím.; vol. 51. (no.2): 325-368. Año. 2020. e-ISSN: 2221-2442. BIBLIOGRAPHIC REWIEW THE FAMOUS FINNISH CHEMIST JOHAN GADOLIN (1760-1852) IN THE LITERATURE BETWEEN THE 19TH AND 21TH CENTURIES El famoso químico finlandés Johan Gadolin (1760-1852) en la literatura entre los siglos XIX y XXI Aleksander Sztejnberga,* a,* Professor Emeritus, University of Opole, Oleska 48, 45-052 Opole, Poland [email protected] Recibido: 19 de octubre de 2020. Aceptado: 10 de diciembre de 2020. ABSTRACT Johan Gadolin (1760-1852), considered the father of Finnish chemistry, was one of the leading chemists of the second half of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century. His life and scientific achievements were described in the literature published between the 19th and 21st centuries. The purpose of this paper is to familiarize readers with the important events in the life of Gadolin and his research activities, in particular some of his research results, as well as his selected publications. In addition, the names of authors of biographical notes or biographies about Gadolin, published in 1839-2017 are presented. Keywords: J. Gadolin; Analytical chemistry; Yttrium; Chemical elements; Finnland & Sverige – XVIII-XIX centuries RESUMEN Johan Gadolin (1760-1852), considerado el padre de la química finlandesa, fue uno de los principales químicos de la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII y la primera mitad del XIX. Su vida y sus logros científicos fueron descritos en la literatura publicada entre los siglos XIX y XXI. El propósito de este artículo es familiarizar a los lectores con los acontecimientos importantes en la vida de Gadolin y sus actividades de investigación, en particular algunos de sus resultados de investigación, así como sus publicaciones seleccionadas. -

Seeking a Forgotten History

HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar About the Authors Sven Beckert is Laird Bell Professor of history Katherine Stevens is a graduate student in at Harvard University and author of the forth- the History of American Civilization Program coming The Empire of Cotton: A Global History. at Harvard studying the history of the spread of slavery and changes to the environment in the antebellum U.S. South. © 2011 Sven Beckert and Katherine Stevens Cover Image: “Memorial Hall” PHOTOGRAPH BY KARTHIK DONDETI, GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN, HARVARD UNIVERSITY 2 Harvard & Slavery introducTION n the fall of 2007, four Harvard undergradu- surprising: Harvard presidents who brought slaves ate students came together in a seminar room to live with them on campus, significant endow- Ito solve a local but nonetheless significant ments drawn from the exploitation of slave labor, historical mystery: to research the historical con- Harvard’s administration and most of its faculty nections between Harvard University and slavery. favoring the suppression of public debates on Inspired by Ruth Simmon’s path-breaking work slavery. A quest that began with fears of finding at Brown University, the seminar’s goal was nothing ended with a new question —how was it to gain a better understanding of the history of that the university had failed for so long to engage the institution in which we were learning and with this elephantine aspect of its history? teaching, and to bring closer to home one of the The following pages will summarize some of greatest issues of American history: slavery. -

BIRTH of BOSTON PURITANS CREATE “CITY UPON a HILL” by Our Newssheet Writer in Boston September 8, 1630

BIRTH OF BOSTON PURITANS CREATE “CITY UPON A HILL” By our newssheet writer in Boston September 8, 1630 URITAN elders declared yesterday that the Shawmut Peninsula will be called P“Boston” in the future. The seat of government of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which began two years ago, will also be in Boston. It follows a meeting between John Winthrop, the colony’s elected governor and clergyman William Blackstone, one of the first settlers to live in Trimount on the peninsula, so called because of its three “mountains.” Blackstone recommended its spring waters. Winthrop (pictured) left England earlier this year to lead ships across the Atlantic. Of the hundreds of passengers on board, many were Puritans seeking religious freedom, eager to start a new life in New England. They had prepared well, bringing many horses and cows with them. The new governor, a member of the English upper classes, brought the royal charter of the Massachusetts Bay Company with him. However, the company’s charter did not impose control from England—the colony would be effectively self-governing. Arriving in Cape Ann, the passengers went ashore and picked fresh strawberries—a welcome change from shipboard life! Colonists had previously settled in the area, but dwellings had been abandoned after many had died in drastically reduced by disease. But Winthrop the harsh winter or were starving. is taking few chances by spreading out One early colonist was Roger Conant, who settlements to make it difficult for potentially established Salem near the Native Naumkeag hostile groups to attack. people. But Winthrop and the other Puritan In time, Winthrop believes many more leaders chose not to settle there, but to continue Puritans will flock to his “City upon a Hill” to the search for their own Promised Land. -

Surviving the First Year of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, 1630-1631 Memoir of Roger Clap, Ca

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox American Beginnings: The European Presence in North America, 1492-1690 Marguerite Mullaney Nantasket Beach, Massachusetts, May “shift for ourselves in a forlorn place in this wilderness” Surviving the First Year of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, 1630-1631 Memoir of Roger Clap, ca. 1680s, excerpts * Roger Clap [Clapp] arrived in New England in May 1630 at age 21, having overcome his father's opposition to his emigration. In his seventies he began his memoir to tell his children of "God's remarkable providences . in bringing me to this land." A devout man, he interprets the lack of food for his body as part of God's providing food for the soul, in this case the souls of the Puritans as they created their religious haven. thought good, my dear children, to leave with you some account of God’s remarkable providences to me, in bringing me into this land and placing me here among his dear servants and in his house, who I am most unworthy of the least of his mercies. The Scripture requireth us to tell God’s wondrous works to our children, that they may tell them to their children, that God may have glory throughout all ages. Amen. I was born in England, in Sallcom, in Devonshire, in the year of our Lord 1609. My father was a man fearing God, and in good esteem among God’s faithful servants. His outward estate was not great, I think not above £80 per annum.1 We were five brethren (of which I was the youngest) and two sisters. -

Bostonians and Their Neighbors As Pack Rats

Bostonians and Their Neighbors as Pack Rats Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/24/2/141/2744123/aarc_24_2_t041107403161g77.pdf by guest on 27 September 2021 By L. H. BUTTERFIELD* Massachusetts Historical Society HE two-legged pack rat has been a common species in Boston and its neighborhood since the seventeenth century. Thanks Tto his activity the archival and manuscript resources concen- trated in the Boston area, if we extend it slightly north to include Salem and slightly west to include Worcester, are so rich and diverse as to be almost beyond the dreams of avarice. Not quite, of course, because Boston institutions and the super—pack rats who direct them are still eager to add to their resources of this kind, and constantly do. The admirable and long-awaited Guide to Archives and Manu- scripts in the United States, compiled by the National Historical Publications Commission and now in press, contains entries for be- tween 50 and 60 institutions holding archival and manuscript ma- terials in the Greater Boston area, with the immense complex of the Harvard University libraries in Cambridge counting only as one.1 The merest skimming of these entries indicates that all the activities of man may be studied from abundant accumulations of written records held by these institutions, some of them vast, some small, some general in their scope, others highly specialized. Among the fields in which there are distinguished holdings—one may say that specialists will neglect them only at their peril—are, first of all, American history and American literature, most of the sciences and the history of science, law and medicine, theology and church his- tory, the fine arts, finance and industry, maritime life, education, and reform. -

Cavendish the Experimental Life

Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Gerd Graßhoff, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Klaus Thoden, Dirk Wintergrün. The Edition Open Access (EOA) platform was founded to bring together publi- cation initiatives seeking to disseminate the results of scholarly work in a format that combines traditional publications with the digital medium. It currently hosts the open-access publications of the “Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge” (MPRL) and “Edition Open Sources” (EOS). EOA is open to host other open access initiatives similar in conception and spirit, in accordance with the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the sciences and humanities, which was launched by the Max Planck Society in 2003. By combining the advantages of traditional publications and the digital medium, the platform offers a new way of publishing research and of studying historical topics or current issues in relation to primary materials that are otherwise not easily available. The volumes are available both as printed books and as online open access publications. They are directed at scholars and students of various disciplines, and at a broader public interested in how science shapes our world. Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach Studies 7 Studies 7 Communicated by Jed Z. Buchwald Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Bendix Düker, Caroline Frank, Beatrice Hermann, Beatrice Hilke Image Processing: Digitization Group of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover Image: Chemical Laboratory. -

Back Matter (PDF)

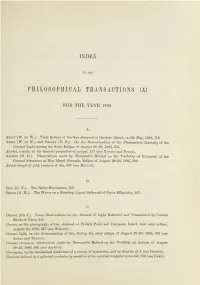

INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS (A) FOR THE YEAR 1894. A. Arc spectrum of electrolytic ,iron on the photographic, 983 (see Lockyer). B. Bakerian L ecture.—On the Relations between the Viscosity (Internal 1 riction) of Liquids and then Chemical Nature, 397 (see T iiorpe and R odger). Bessemer process, the spectroscopic phenomena and thermo-chemistry of the, 1041 IIarimo). C. Capstick (J. W.). On the Ratio of the Specific Heats of the Paraffins, and their Monohalogei.. Derivatives, 1. Carbon dioxide, on the specific heat of, at constant volume, 943 (sec ). Carbon dioxide, the specific heat of, as a function of temperatuie, ddl (mo I j . , , Crystals, an instrument of precision for producing monochromatic light of any desire. ua\e- eng », * its use in the investigation of the optical properties of, did (see it MDCCCXCIV.— A. ^ <'rystals of artificial preparations, an instrument for grinding section-plates and prisms of, 887 (see Tutton). Cubic surface, on a special form of the general equation of a, and on a diagram representing the twenty- seven lines on the surface, 37 (see Taylor). •Cables, on plane, 247 (see Scott). D. D unkeelky (S.). On the Whirling and Vibration of Shafts, 279. Dynamical theory of the electric and luminifei’ous medium, a, 719 (see Larmor). E. Eclipse of the sun, April 16, 1893, preliminary report on the results obtained with the prismatic cameras during the total, 711 (see Lockyer). Electric and luminiferous medium, a dynamical theory of the, 719 (see Larmor). Electrolytic iron, on the photographic arc spectrum of, 983 (see Lockyer). Equation of the general cubic surface, 37 (see Taylor). -

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town Cl740-Cl820

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town cl740-cl820 Neville Flavell PhD The Division of Adult Continuing Education University of Sheffield February 1996 Volume One THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF SHEFFIELD AND THE GROWTH OF THE TOWN cl740-c 1820 Neville Flavell February 1996 SUMMARY In the early eighteenth century Sheffield was a modest industrial town with an established reputation for cutlery and hardware. It was, however, far inland, off the main highway network and twenty miles from the nearest navigation. One might say that with those disadvantages its future looked distinctly unpromising. A century later, Sheffield was a maker of plated goods and silverware of international repute, was en route to world supremacy in steel, and had already become the world's greatest producer of cutlery and edge tools. How did it happen? Internal economies of scale vastly outweighed deficiencies. Skills, innovations and discoveries, entrepreneurs, investment, key local resources (water power, coal, wood and iron), and a rapidly growing labour force swelled largely by immigrants from the region were paramount. Each of these, together with external credit, improved transport and ever-widening markets, played a significant part in the town's metamorphosis. Economic and population growth were accompanied by a series of urban developments which first pushed outward the existing boundaries. Considerable infill of gardens and orchards followed, with further peripheral expansion overspilling into adjacent townships. New industrial, commercial and civic building, most of it within the central area, reinforced this second phase. A period of retrenchment coincided with the French and Napoleonic wars, before a renewed surge of construction restored the impetus. -

Philosophical Transactions (A)

INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS (A) FOR THE YEAR 1889. A. A bney (W. de W.). Total Eclipse of the San observed at Caroline Island, on 6th May, 1883, 119. A bney (W. de W.) and T horpe (T. E.). On the Determination of the Photometric Intensity of the Coronal Light during the Solar Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 363. Alcohol, a study of the thermal properties of propyl, 137 (see R amsay and Y oung). Archer (R. H.). Observations made by Newcomb’s Method on the Visibility of Extension of the Coronal Streamers at Hog Island, Grenada, Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 382. Atomic weight of gold, revision of the, 395 (see Mallet). B. B oys (C. V.). The Radio-Micrometer, 159. B ryan (G. H.). The Waves on a Rotating Liquid Spheroid of Finite Ellipticity, 187. C. Conroy (Sir J.). Some Observations on the Amount of Light Reflected and Transmitted by Certain 'Kinds of Glass, 245. Corona, on the photographs of the, obtained at Prickly Point and Carriacou Island, total solar eclipse, August 29, 1886, 347 (see W esley). Coronal light, on the determination of the, during the solar eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 363 (see Abney and Thorpe). Coronal streamers, observations made by Newcomb’s Method on the Visibility of, Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 382 (see A rcher). Cosmogony, on the mechanical conditions of a swarm of meteorites, and on theories of, 1 (see Darwin). Currents induced in a spherical conductor by variation of an external magnetic potential, 513 (see Lamb). 520 INDEX. -

![Kemivandring ‐ Uppsala]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0090/kemivandring-uppsala-1460090.webp)

Kemivandring ‐ Uppsala]

Uppsala Universitet [KEMIVANDRING ‐ UPPSALA] En idéhistorisk vandring med nedslag i kemins Uppsala och historiska omvärld i urval. Karta: 1. Academia Carolina, Riddartorget 2. Gustavianum 3. Skytteanum 4. Fängelset vid domtrappan 5. Kungliga vetenskaps‐societeten 6. St. Eriks källa, akademikvarnen 7. Starten för branden 1702 8. Celsiushuset 9. Scheeles apotek (revs 1960) 10. Gamla kemikum, Wallerius/Bergman 11. Carolina Rediviva 12. Nya Kemikum/Engelska parken 13. The Svedberg laboratoriet 14. BMC, Uppsala Biomedicinska centrum 15. Ångströmlaboratoriet Uppsala Universitet [KEMIVANDRING ‐ UPPSALA] Uppsala universitet: kort historik[Karta: 1‐4] Uppsala universitet grundades 1477 av katolska kyrkan som utbildningsinstitution för präster och teologer. Det är nordens äldsta universitet och var vid tidpunkten världens nordligaste universitet. Domkyrkorna utbildade präster men för högre utbildningar var svenskar från 1200‐ talet och framåt tvungna att studera vid utländska universitet i till exempel Paris eller Rostock. Den starkast drivande kraften för bildandet av Uppsala universitet var Jakob Ulvsson som var Sveriges ärkebiskop mellan år 1469‐1515 och därmed den som innehaft ämbetet längst (46 år). Vid domkyrkan mot riddartorget finns en staty av Jakob Ulvsson av konstnären och skulptören Christian Eriksson. Statyns porträttlikhet med Ulvsson är förstås tvivelaktig eftersom man inte vet hur Jakob Ulvsson såg ut. Konstnären studerade i Paris tillsammans med Nathan Söderblom och det sägs att Eriksson hade honom som förebild för Ulvsson statyn och som därmed fick mycket lika ansiktsdrag som Söderblom. (Nathan Söderblom var ärkebiskop i Uppsala 1914‐ 1931, grundade den Ekumeniska rörelsen och fick Nobels fredspris 1930). Till en början bestod undervisningen vid Uppsala universitet främst av filosofi, juridik och teologi. Någon teknisk eller naturvetenskap utbildning fanns inte vid denna tidpunkt. -

Newsletter O U R S E L E C T I O N a T T H E L O N D O N International Antiquarian B O O K F a I R O L Y M P I a 24–26 M a Y 2012

11 20 BOHMAN RICE AT BE 11 20 BOHMAN RICE AT BE 11 20 BOHMAN RICE AT BE 11 20 BOHMAN RICE AT BE 11 20 BOHMAN RICE AT BE 11 20 BOHMAN RICE AT BE 11 20 BOHMAN RICE AT BE 11 20 BOHMAN RICE AT BE 11 20 BOHMAN RICE AT BE 11 20 BOHMAN RICE AT BE 11 20 BOHMAN RICE AT BE 11 20 BOHMAN RICE AT BE SWEDEN SVERIGE LA SUÈDE SAINT BRIDGET 1303–1373 LINNAEUS 1707–1778 STRINDBERG 1849–1912 Newsletter OUR SELECTION AT THE LONDON INTERNATIONAL ANTIQUARIAN BOOK FAIR OLYMPIA 24–26 MAY 2012 jakobsgatan 27b / p.o box 16394 / se-103 27 stockholm, sweden MATS REHNSTRÖM Rare books tel. +46 8 411 92 24 / fax: +46 8 411 94 61 / e-mail: [email protected] 4. Science, Medicine & The books offered below are subject to prior sale. 1. AGARDH, C. A. Icones algarum europae- arum. Représentation d’algues européennes Technology suivie de celle d’espèces exotiques les plus re- marquables recemment découvertes. Avec 40 planches coloriées. Leipzig, L. Voss, 1828-35. 8:o. (90) pp. & 40 handcoloured litographed plates. + AGARDH, JACOB A. Algæ maris Mediterranei et Adriatici, observationes in di- agnosin specierumet dispositionem generum. Paris, A. Saintin, 1842. 8:o (2),X,164 pp. Slightly worn contemporary full calf with broad raised 25. bands, gilt and blind tooled spine and green mo- rocco spine labels (bound by Taylor & Walton). Marbled edges. Boards with narrow gilt and blind tooled borders and extremities. Slightly faded on upper part of the boards. Spine in part slightly miscoloured.