1987 by the Ecological Society of America DYNAMICS of MOJAVE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life History and Ecology of the Pinacate Beetle, Eleodes Armatus

The Coleopterists Bulletin, 38(2):150-159. 1984. THE LIFE HISTORY AND ECOLOGY OF THE PINACATE BEETLE, ELEODES ARMA TUS LECONTE (TENEBRIONIDAE) DONALD B. THOMAS U.S. Livestock Insects Laboratory, P.O. Box 232, Kerrville, TX 78028 ABSTRACT Eleodes armatus LeConte, the pinacate beetle, occurs throughout the warm deserts and intermontane valleys of the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. It is a scavenger, feeding mainly on plant and animal detritus, and it hides in rodent burrows during times of temperature extremes. Adult activity peaks in the fall but it may occur at any time of the year. Females produce several hundred eggs per season and adults may live for more than 1 year. Larvae are fossorial and require 9 months to develop. The broad ecological, geographical, temporal and dietary range of this beetle may be in part attributable to its defense mechanisms (repugnatorial secretions and allied be- havior) against vertebrate predators. On the black earth on which the ice plants bloomed, hundreds of black stink bugs crawled. And many of them stuck their tails up in the air. "Look at all them stink bugs," Hazel remarked, grateful to the bugs for being there. "They're interesting," said Doc. "Well, what they got their asses up in the air for?" Doc rolled up his wool socks and put them in the rubber boots and from his pocket he brought out dry socks and a pair of thin moccasins. "I don't know why," he said, "I looked them up recently-they're very common animals and one of the commonest things they do is put their tails up in the air. -

Research Paper a Review of Goji Berry (Lycium Barbarum) in Traditional Chinese Medicine As a Promising Organic Superfood And

Academia Journal of Medicinal Plants 6(12): 437-445, December 2018 DOI: 10.15413/ajmp.2018.0186 ISSN: 2315-7720 ©2018 Academia Publishing Research Paper A review of Goji berry (Lycium barbarum) in Traditional Chinese medicine as a promising organic superfood and superfruit in modern industry Accepted 3rd December, 2018 ABSTRACT Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has been used for thousands of years by different generations in China and other Asian countries as foods to promote good health and as drugs to treat disease. Goji berry (Lycium barbarum), as a Chinese traditional herb and food supplement, contains many nutrients and phytochemicals, such as polysaccharides, scopoletin, the glucosylated precursor, amino acids, flaconoids, carotenoids, vitamins and minerals. It has positive effects on anitcancer, antioxidant activities, retinal function preservation, anti-diabetes, immune function and anti-fatigue. Widely used in traditional Chinese medicine, Goji berries can be sold as a dietary supplement or classified as nutraceutical food due to their long and safe traditional use. Modern Goji pharmacological actions improve function and enhance the body ,s ability to adapt to a variety of noxious stimuli; it significantly inhibits the generation and spread of cancer cells and can improve eyesight and increase reserves of muscle and liver glycogens which may increase human energy and has anti-fatigue effect. Goji berries may improve brain function and enhance learning and memory. It may boost the body ,s adaptive defences, and significantly reduce the levels of serum cholesterol and triglyceride, it may help weight loss and obesity and treats chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. At Mohamad Hesam Shahrajabian1,2, Wenli present, they are considered functional food with many beneficial effects, which is Sun1,2 and Qi Cheng1,2* why they have become more popular recently, especially in Europe, North America and Australia, as they are considered as superfood with highly nutritive and 1 Biotechnology Research Institute, antioxidant properties. -

GOOSEBERRYLEAF GLOBEMALLOW Sphaeralcea Grossulariifolia (Hook

GOOSEBERRYLEAF GLOBEMALLOW Sphaeralcea grossulariifolia (Hook. & Arn.) Rydb. Malvaceae – Mallow family Corey L. Gucker & Nancy L. Shaw | 2018 ORGANIZATION NOMENCLATURE Sphaeralcea grossulariifolia (Hook. & Arn.) Names, subtaxa, chromosome number(s), hybridization. Rydb., hereafter referred to as gooseberryleaf globemallow, belongs to the Malveae tribe of the Malvaceae or mallow family (Kearney 1935; La Duke 2016). Range, habitat, plant associations, elevation, soils. NRCS Plant Code. SPGR2 (USDA NRCS 2017). Subtaxa. The Flora of North America (La Duke 2016) does not recognize any varieties or Life form, morphology, distinguishing characteristics, reproduction. subspecies. Synonyms. Malvastrum coccineum (Nuttall) A. Gray var. grossulariifolium (Hooker & Arnott) Growth rate, successional status, disturbance ecology, importance to animals/people. Torrey, M. grossulariifolium (Hooker & Arnott) A. Gray, Sida grossulariifolia Hooker & Arnott, Sphaeralcea grossulariifolia subsp. pedata Current or potential uses in restoration. (Torrey ex A. Gray) Kearney, S. grossulariifolia var. pedata (Torrey ex A. Gray) Kearney, S. pedata Torrey ex A. Gray (La Duke 2016). Seed sourcing, wildland seed collection, seed cleaning, storage, Common Names. Gooseberryleaf globemallow, testing and marketing standards. current-leaf globemallow (La Duke 2016). Chromosome Number. Chromosome number is stable, 2n = 20, and plants are diploid (La Duke Recommendations/guidelines for producing seed. 2016). Hybridization. Hybridization occurs within the Sphaeralcea genus. -

![Germination and Seedling Establishment of Spiny Hopsage (Grayia Spinosa [Hook.] Moq.)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8079/germination-and-seedling-establishment-of-spiny-hopsage-grayia-spinosa-hook-moq-328079.webp)

Germination and Seedling Establishment of Spiny Hopsage (Grayia Spinosa [Hook.] Moq.)

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Nancy L. Shaw for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Crop and Soil Sciences presented on March 19, 1992 Title: Germination and Seedling Establishment of Spiny Hopsage (Grayia Spinosa [Hook.] Moq.) Abstract approved:_Redactedfor Privacy von r. ULdUe Reestablishment of spiny hopsage(Grayia spinosa [Hook.] Moq.) where depleted or lost on shrub steppe sites can improve forage, plant cover, and soil stabilization. The objectives of this study were to: 1) determine direct-seeding requirements; 2) develop optimum germination pretreatments; and 3) examine dormancy mechanisms in spiny hopsage fruits and seeds. The effects of seed source, planting date,and site preparation method onseed germination and seedling establishment (SE) were examined at Birds of Prey and Reynolds Creek in southwestern Idaho. Three seed sources were planted on rough or compact seedbeds on 4 dates in 1986-87 and 3 dates in 1987-88. Exposure to cool-moist environments improved spring SE from early fall (EF) and late fall (LF) plantings. Few seedlings emerged from early (ESp) or late spring (LSp) plantings. SE was low at: 1 site in 1986-87 and atboth sites in 1987-88, probably due to lack of precipitation. For the successful 1986-87 planting, seedling density was greater on rough compared to compact seedbeds in April andMay, possiblydue to improved microclimate conditions. Growth rate varied among seed sources, but seedlings developed a deep taproot (mean length 266 mm) with few lateral roots the first season. Seeds were planted on 3 dates in 1986-87 and 1987-88, andnylon bags containing seeds were planted on 4 dates each year to study microenvironment effects on germination (G), germination rate (GR), and SE. -

IP Athos Renewable Energy Project, Plan of Development, Appendix D.2

APPENDIX D.2 Plant Survey Memorandum Athos Memo Report To: Aspen Environmental Group From: Lehong Chow, Ironwood Consulting, Inc. Date: April 3, 2019 Re: Athos Supplemental Spring 2019 Botanical Surveys This memo report presents the methods and results for supplemental botanical surveys conducted for the Athos Solar Energy Project in March 2019 and supplements the Biological Resources Technical Report (BRTR; Ironwood 2019) which reported on field surveys conducted in 2018. BACKGROUND Botanical surveys were previously conducted in the spring and fall of 2018 for the entirety of the project site for the Athos Solar Energy Project (Athos). However, due to insufficient rain, many plant species did not germinate for proper identification during 2018 spring surveys. Fall surveys in 2018 were conducted only on a reconnaissance-level due to low levels of rain. Regional winter rainfall from the two nearest weather stations showed rainfall averaging at 0.1 inches during botanical surveys conducted in 2018 (Ironwood, 2019). In addition, gen-tie alignments have changed slightly and alternatives, access roads and spur roads have been added. PURPOSE The purpose of this survey was to survey all new additions and re-survey areas of interest including public lands (limited to portions of the gen-tie segments), parcels supporting native vegetation and habitat, and windblown sandy areas where sensitive plant species may occur. The private land parcels in current or former agricultural use were not surveyed (parcel groups A, B, C, E, and part of G). METHODS Survey Areas: The area surveyed for biological resources included the entirety of gen-tie routes (including alternates), spur roads, access roads on public land, parcels supporting native vegetation (parcel groups D and F), and areas covered by windblown sand where sensitive species may occur (portion of parcel group G). -

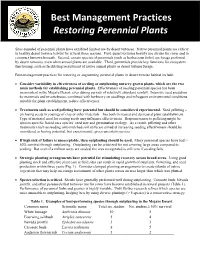

Best Management Practices Restoring Perennial Plants

Best Management Practices Restoring Perennial Plants Sites denuded of perennial plants have exhibited limited use by desert tortoises. Native perennial plants are critical to healthy desert tortoise habitat for at least three reasons. First, desert tortoises heavily use shrubs for cover and to construct burrows beneath. Second, certain species of perennials (such as herbaceous forbs) are forage preferred by desert tortoises, even when annual plants are available. Third, perennials provide key functions for ecosystem functioning, such as facilitating recruitment of native annual plants as desert tortoise forage. Best-management practices for restoring or augmenting perennial plants in desert tortoise habitat include: • Consider variability in effectiveness of seeding or outplanting nursery-grown plants, which are the two main methods for establishing perennial plants. Effectiveness of seeding perennial species has been inconsistent in the Mojave Desert, even during periods of relatively abundant rainfall. Intensive seed predation by mammals and invertebrates, combined with herbivory on seedlings and infrequent environmental conditions suitable for plant establishment, reduce effectiveness. • Treatments such as seed pelleting have potential but should be considered experimental. Seed pelleting – enclosing seeds in coatings of clay or other materials – has both increased and decreased plant establishment. Type of material used for coating seeds may influence effectiveness. Responsiveness to pelleting might be species-specific, based on a species’ seed size and germination ecology. As a result, pelleting and other treatments (such as seeding onto mulched soil surfaces) aimed at increasing seeding effectiveness should be considered as having potential, but experimental, given uncertain success. • If high risk of failure is unacceptable, then outplanting should be used. -

Vegetative Habitat Analysis of Proposed Mine Sites in the Mojave Desert: the First Step Owart Ds Revegetation of Disturbed Desert Communities

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 1993 Vegetative habitat analysis of proposed mine sites in the Mojave Desert: The first step owart ds revegetation of disturbed desert communities Jim Van Brunt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Desert Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Van Brunt, Jim, "Vegetative habitat analysis of proposed mine sites in the Mojave Desert: The first step towards revegetation of disturbed desert communities" (1993). Theses Digitization Project. 663. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/663 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VEGETATIVE HABITAT ANALYSIS OF PROPOSED MINE SITES IN THE MOJAVE DESERT: THE FIRST STEP TOWARDS REVEGETATION OF DISTURBED DESERT COMMUNITIES A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Biology by Jim Van Brunt December 1993 VEGETATIVE HABITAT ANALYSIS OF PROPOSED MINE SITES IN THE MOJAVE DESERT; THE FIRST STEP TOWARDS REVEGETATION OF DISTURBED COMMUNITIES A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State Universityi San Bernardino by Jim Van Brunt December 1993 Approved by: Dr. David Polcyn, ChairVr.M Biologyn-J r Date Dr. Jam/ Ferrari, Dr. Richard Fehn, ABSTRACT Due to changes in the laws that govern mining, mine companies are now required to revegetate any public land they disturb during the mining process. -

Color Plant 2.P65

AG 510 USDA-ARS-Forage and Range Research Lab, Logan, Utah, in conjunction with Utah State University Extension PLANTING GUIDE 105 Writers and Compilers Kevin Jensen, Howard Horton, Ron Reed, Ralph Whitesides, and USDA-ARS-FRRL Utah State University, Logan Utah. 435-797-3066, E-mail: [email protected] Contributors Extension Specialist – Robert Newhall, Plants, Soils, Biometeorology Dept. Utah State University, 435-797-2183, E-mail: [email protected] Fertilization – Dr. Richard Koenig, Plants, Soils, and Biometeorology Dept. Utah State University, 435-797-2278, E-mail: [email protected] Irrigation – Dr. Robert Hill, Biology and Irrigation Engineering Dept. Utah State University, 435-797-1248, E-mail: [email protected] Weed Control – Dr. Steven Dewey, Plants, Soils, and Biometeorology Dept. Utah State University, 435-797-2256, E-mail: [email protected] Seed Quality – Dr. Stanford Young, Plants, Soils, and Biometeorology Dept. Utah State University, 435-797-2082, E-mail: [email protected] Riparian/Wetland Systems – Chris Hoag, Wettland Plant Ecologist, Interagency Riparian/Wetland Project, Plant Materials Center, USDA-NRCS, Aberdeen, Idaho Plant Materials Specialist and Riparian/Wetland Systems – Dan Ogle, USDA-NRCS, Boise, Idaho, 208-378-5730 Major References Consulted Cool-Season Forage Grass Monograph. 1996. Editors L.E. Moser, D.R. Buxton, and M.D. Casler. American Society of Agronomy Number 34. Alberta Forage Manual. 1992. Print Media Branch, Alberta Agriculture, 7000-113 Street, Edmonton, Alberta, T6H 5T6. Forages Volume 1: An Introduction to Grassland Agriculture. 1995. Editors R.F. Barnes, D.A. Miller, and C.J. Miller. Iowa State University Press. USDA, NRCS 1999. -

Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve San Diego County Technical Appendices

Final Area Specific Management Directives for Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve San Diego County Technical Appendices June 2008 Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve Final Area Specific Management Directives Technical Appendices TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A - Botanical Resources Letter Report for Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve APPENDIX B - Draft Baseline Biological Resources Evaluation Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve APPENDIX C - Cultural Resources Phase I Survey and Inventory, Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve, San Diego County, California i June 2008 Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve Final Area Specific Management Directives Technical Appendices APPENDIX A Botanical Resources Letter Report for Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve June 2008 Botanical Resources Letter Report for Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve SUMMARY The Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve (Preserve) support natural habitat areas that have been acquired as part of the San Diego County’s Multiple Species Conservation Program (MSCP), administered by County of San Diego Department of Parks and Recreation (County). The Preserve totals 134.0 acres and consists of three properties referred to in this report as western, central, and eastern. The three properties of the Preserve were surveyed during the spring and summer of 2007 by County of San Diego Temporary Expert Professionals for botanical resources including vegetation mapping and the potential presence of any sensitive plant species. This report documents the findings of these surveys and provides recommendations for management of the Preserve. PROJECT DESCRIPTION, LOCATION, AND SETTING Project Location The Preserve is located within the unincorporated community of Lakeside surrounded by residential development. The western property is located west of Los Coches Road between Calle Lucia Terrace on the south and a private road south of Rock Crest Lane on the north in Lakeside, California. -

Lake Havasu City Recommended Landscaping Plant List

Lake Havasu City Recommended Landscaping Plant List Lake Havasu City Recommended Landscaping Plant List Disclaimer Lake Havasu City has revised the recommended landscaping plant list. This new list consists of plants that can be adapted to desert environments in the Southwestern United States. This list only contains water conscious species classified as having very low, low, and low-medium water use requirements. Species that are classified as having medium or higher water use requirements were not permitted on this list. Such water use classification is determined by the type of plant, its average size, and its water requirements compared to other plants. For example, a large tree may be classified as having low water use requirements if it requires a low amount of water compared to most other large trees. This list is not intended to restrict what plants residents choose to plant in their yards, and this list may include plant species that may not survive or prosper in certain desert microclimates such as those with lower elevations or higher temperatures. In addition, this list is not intended to be a list of the only plants allowed in the region, nor is it intended to be an exhaustive list of all desert-appropriate plants capable of surviving in the region. This list was created with the intention to help residents, businesses, and landscapers make informed decisions on which plants to landscape that are water conscious and appropriate for specific environmental conditions. Lake Havasu City does not require the use of any or all plants found on this list. List Characteristics This list is divided between trees, shrubs, groundcovers, vines, succulents and perennials. -

Biogenic Volatile Organic Compound Emissions from Desert Vegetation of the Southwestern US

ARTICLE IN PRESS Atmospheric Environment 40 (2006) 1645–1660 www.elsevier.com/locate/atmosenv Biogenic volatile organic compound emissions from desert vegetation of the southwestern US Chris Gerona,Ã, Alex Guentherb, Jim Greenbergb, Thomas Karlb, Rei Rasmussenc aUnited States Environmental Protection Agency, National Risk Management Research Laboratory, Research Triangle Park, NC 27711, USA bNational Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO 80303, USA cOregon Graduate Institute, Portland, OR 97291, USA Received 27 July 2005; received in revised form 25 October 2005; accepted 25 October 2005 Abstract Thirteen common plant species in the Mojave and Sonoran Desert regions of the western US were tested for emissions of biogenic non-methane volatile organic compounds (BVOCs). Only two of the species examined emitted isoprene at rates of 10 mgCgÀ1 hÀ1or greater. These species accounted for o10% of the estimated vegetative biomass in these arid regions of low biomass density, indicating that these ecosystems are not likely a strong source of isoprene. However, isoprene emissions from these species continued to increase at much higher leaf temperatures than is observed from species in other ecosystems. Five species, including members of the Ambrosia genus, emitted monoterpenes at rates exceeding 2 mgCgÀ1 hÀ1. Emissions of oxygenated compounds, such as methanol, ethanol, acetone/propanal, and hexanol, from cut branches of several species exceeded 10 mgCgÀ1 hÀ1, warranting further investigation in these ecosystems. Model extrapolation of isoprene emission measurements verifies recently published observations that desert vegetation is a small source of isoprene relative to forests. Annual and daily total model isoprene emission estimates from an eastern US mixed forest landscape were 10–30 times greater than isoprene emissions estimated from the Mojave site. -

Literature Cited

Literature Cited Robert W. Kiger, Editor This is a consolidated list of all works cited in volume 9, whether as selected references, in text, or in nomenclatural contexts. In citations of articles, both here and in the taxonomic treatments, and also in nomenclatural citations, the titles of serials are rendered in the forms recommended in G. D. R. Bridson and E. R. Smith (1991), Bridson (2004), and Bridson and D. W. Brown (http://fmhibd.library.cmu.edu/fmi/iwp/cgi?-db=BPH_Online&-loadframes). When those forms are abbreviated, as most are, cross references to the corresponding full serial titles are interpolated here alphabetically by abbreviated form. In nomenclatural citations (only), book titles are rendered in the abbreviated forms recommended in F. A. Stafleu and R. S. Cowan (1976–1988) and Stafleu et al. (1992–2009). Here, those abbreviated forms are indicated parenthetically following the full citations of the corresponding works, and cross references to the full citations are interpolated in the list alphabetically by abbreviated form. Two or more works published in the same year by the same author or group of coauthors will be distinguished uniquely and consistently throughout all volumes of Flora of North America by lower-case letters (b, c, d, ...) suffixed to the date for the second and subsequent works in the set. The suffixes are assigned in order of editorial encounter and do not reflect chronological sequence of publication. The first work by any particular author or group from any given year carries the implicit date suffix “a”; thus, the sequence of explicit suffixes begins with “b”.