Best Management Practices Restoring Perennial Plants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life History and Ecology of the Pinacate Beetle, Eleodes Armatus

The Coleopterists Bulletin, 38(2):150-159. 1984. THE LIFE HISTORY AND ECOLOGY OF THE PINACATE BEETLE, ELEODES ARMA TUS LECONTE (TENEBRIONIDAE) DONALD B. THOMAS U.S. Livestock Insects Laboratory, P.O. Box 232, Kerrville, TX 78028 ABSTRACT Eleodes armatus LeConte, the pinacate beetle, occurs throughout the warm deserts and intermontane valleys of the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. It is a scavenger, feeding mainly on plant and animal detritus, and it hides in rodent burrows during times of temperature extremes. Adult activity peaks in the fall but it may occur at any time of the year. Females produce several hundred eggs per season and adults may live for more than 1 year. Larvae are fossorial and require 9 months to develop. The broad ecological, geographical, temporal and dietary range of this beetle may be in part attributable to its defense mechanisms (repugnatorial secretions and allied be- havior) against vertebrate predators. On the black earth on which the ice plants bloomed, hundreds of black stink bugs crawled. And many of them stuck their tails up in the air. "Look at all them stink bugs," Hazel remarked, grateful to the bugs for being there. "They're interesting," said Doc. "Well, what they got their asses up in the air for?" Doc rolled up his wool socks and put them in the rubber boots and from his pocket he brought out dry socks and a pair of thin moccasins. "I don't know why," he said, "I looked them up recently-they're very common animals and one of the commonest things they do is put their tails up in the air. -

Research Paper a Review of Goji Berry (Lycium Barbarum) in Traditional Chinese Medicine As a Promising Organic Superfood And

Academia Journal of Medicinal Plants 6(12): 437-445, December 2018 DOI: 10.15413/ajmp.2018.0186 ISSN: 2315-7720 ©2018 Academia Publishing Research Paper A review of Goji berry (Lycium barbarum) in Traditional Chinese medicine as a promising organic superfood and superfruit in modern industry Accepted 3rd December, 2018 ABSTRACT Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has been used for thousands of years by different generations in China and other Asian countries as foods to promote good health and as drugs to treat disease. Goji berry (Lycium barbarum), as a Chinese traditional herb and food supplement, contains many nutrients and phytochemicals, such as polysaccharides, scopoletin, the glucosylated precursor, amino acids, flaconoids, carotenoids, vitamins and minerals. It has positive effects on anitcancer, antioxidant activities, retinal function preservation, anti-diabetes, immune function and anti-fatigue. Widely used in traditional Chinese medicine, Goji berries can be sold as a dietary supplement or classified as nutraceutical food due to their long and safe traditional use. Modern Goji pharmacological actions improve function and enhance the body ,s ability to adapt to a variety of noxious stimuli; it significantly inhibits the generation and spread of cancer cells and can improve eyesight and increase reserves of muscle and liver glycogens which may increase human energy and has anti-fatigue effect. Goji berries may improve brain function and enhance learning and memory. It may boost the body ,s adaptive defences, and significantly reduce the levels of serum cholesterol and triglyceride, it may help weight loss and obesity and treats chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. At Mohamad Hesam Shahrajabian1,2, Wenli present, they are considered functional food with many beneficial effects, which is Sun1,2 and Qi Cheng1,2* why they have become more popular recently, especially in Europe, North America and Australia, as they are considered as superfood with highly nutritive and 1 Biotechnology Research Institute, antioxidant properties. -

IP Athos Renewable Energy Project, Plan of Development, Appendix D.2

APPENDIX D.2 Plant Survey Memorandum Athos Memo Report To: Aspen Environmental Group From: Lehong Chow, Ironwood Consulting, Inc. Date: April 3, 2019 Re: Athos Supplemental Spring 2019 Botanical Surveys This memo report presents the methods and results for supplemental botanical surveys conducted for the Athos Solar Energy Project in March 2019 and supplements the Biological Resources Technical Report (BRTR; Ironwood 2019) which reported on field surveys conducted in 2018. BACKGROUND Botanical surveys were previously conducted in the spring and fall of 2018 for the entirety of the project site for the Athos Solar Energy Project (Athos). However, due to insufficient rain, many plant species did not germinate for proper identification during 2018 spring surveys. Fall surveys in 2018 were conducted only on a reconnaissance-level due to low levels of rain. Regional winter rainfall from the two nearest weather stations showed rainfall averaging at 0.1 inches during botanical surveys conducted in 2018 (Ironwood, 2019). In addition, gen-tie alignments have changed slightly and alternatives, access roads and spur roads have been added. PURPOSE The purpose of this survey was to survey all new additions and re-survey areas of interest including public lands (limited to portions of the gen-tie segments), parcels supporting native vegetation and habitat, and windblown sandy areas where sensitive plant species may occur. The private land parcels in current or former agricultural use were not surveyed (parcel groups A, B, C, E, and part of G). METHODS Survey Areas: The area surveyed for biological resources included the entirety of gen-tie routes (including alternates), spur roads, access roads on public land, parcels supporting native vegetation (parcel groups D and F), and areas covered by windblown sand where sensitive species may occur (portion of parcel group G). -

Vegetative Habitat Analysis of Proposed Mine Sites in the Mojave Desert: the First Step Owart Ds Revegetation of Disturbed Desert Communities

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 1993 Vegetative habitat analysis of proposed mine sites in the Mojave Desert: The first step owart ds revegetation of disturbed desert communities Jim Van Brunt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Desert Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Van Brunt, Jim, "Vegetative habitat analysis of proposed mine sites in the Mojave Desert: The first step towards revegetation of disturbed desert communities" (1993). Theses Digitization Project. 663. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/663 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VEGETATIVE HABITAT ANALYSIS OF PROPOSED MINE SITES IN THE MOJAVE DESERT: THE FIRST STEP TOWARDS REVEGETATION OF DISTURBED DESERT COMMUNITIES A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Biology by Jim Van Brunt December 1993 VEGETATIVE HABITAT ANALYSIS OF PROPOSED MINE SITES IN THE MOJAVE DESERT; THE FIRST STEP TOWARDS REVEGETATION OF DISTURBED COMMUNITIES A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State Universityi San Bernardino by Jim Van Brunt December 1993 Approved by: Dr. David Polcyn, ChairVr.M Biologyn-J r Date Dr. Jam/ Ferrari, Dr. Richard Fehn, ABSTRACT Due to changes in the laws that govern mining, mine companies are now required to revegetate any public land they disturb during the mining process. -

Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve San Diego County Technical Appendices

Final Area Specific Management Directives for Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve San Diego County Technical Appendices June 2008 Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve Final Area Specific Management Directives Technical Appendices TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A - Botanical Resources Letter Report for Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve APPENDIX B - Draft Baseline Biological Resources Evaluation Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve APPENDIX C - Cultural Resources Phase I Survey and Inventory, Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve, San Diego County, California i June 2008 Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve Final Area Specific Management Directives Technical Appendices APPENDIX A Botanical Resources Letter Report for Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve June 2008 Botanical Resources Letter Report for Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve SUMMARY The Lakeside Linkage Open Space Preserve (Preserve) support natural habitat areas that have been acquired as part of the San Diego County’s Multiple Species Conservation Program (MSCP), administered by County of San Diego Department of Parks and Recreation (County). The Preserve totals 134.0 acres and consists of three properties referred to in this report as western, central, and eastern. The three properties of the Preserve were surveyed during the spring and summer of 2007 by County of San Diego Temporary Expert Professionals for botanical resources including vegetation mapping and the potential presence of any sensitive plant species. This report documents the findings of these surveys and provides recommendations for management of the Preserve. PROJECT DESCRIPTION, LOCATION, AND SETTING Project Location The Preserve is located within the unincorporated community of Lakeside surrounded by residential development. The western property is located west of Los Coches Road between Calle Lucia Terrace on the south and a private road south of Rock Crest Lane on the north in Lakeside, California. -

Biogenic Volatile Organic Compound Emissions from Desert Vegetation of the Southwestern US

ARTICLE IN PRESS Atmospheric Environment 40 (2006) 1645–1660 www.elsevier.com/locate/atmosenv Biogenic volatile organic compound emissions from desert vegetation of the southwestern US Chris Gerona,Ã, Alex Guentherb, Jim Greenbergb, Thomas Karlb, Rei Rasmussenc aUnited States Environmental Protection Agency, National Risk Management Research Laboratory, Research Triangle Park, NC 27711, USA bNational Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO 80303, USA cOregon Graduate Institute, Portland, OR 97291, USA Received 27 July 2005; received in revised form 25 October 2005; accepted 25 October 2005 Abstract Thirteen common plant species in the Mojave and Sonoran Desert regions of the western US were tested for emissions of biogenic non-methane volatile organic compounds (BVOCs). Only two of the species examined emitted isoprene at rates of 10 mgCgÀ1 hÀ1or greater. These species accounted for o10% of the estimated vegetative biomass in these arid regions of low biomass density, indicating that these ecosystems are not likely a strong source of isoprene. However, isoprene emissions from these species continued to increase at much higher leaf temperatures than is observed from species in other ecosystems. Five species, including members of the Ambrosia genus, emitted monoterpenes at rates exceeding 2 mgCgÀ1 hÀ1. Emissions of oxygenated compounds, such as methanol, ethanol, acetone/propanal, and hexanol, from cut branches of several species exceeded 10 mgCgÀ1 hÀ1, warranting further investigation in these ecosystems. Model extrapolation of isoprene emission measurements verifies recently published observations that desert vegetation is a small source of isoprene relative to forests. Annual and daily total model isoprene emission estimates from an eastern US mixed forest landscape were 10–30 times greater than isoprene emissions estimated from the Mojave site. -

Approved Plant Species (By Watershed) for Use in Riparian Mitigation Areas, Pima County, Arizona

APPROVED PLANT SPECIES (BY WATERSHED) FOR USE IN RIPARIAN MITIGATION AREAS, PIMA COUNTY, ARIZONA Western Pima County Botanical Name Common Name Life Form Water Requirements HYDRORIPARIAN TREES Celtis laevigata (Celtis reticulata) Netleaf/Canyon hackberry Perennial Tree Moderate Populus fremontii ssp. fremontii Fremont cottonwood Perennial Tree High Salix gooddingii Goodding’s willow Perennial Tree High SHRUBS Celtis ehrenbergiana (Celtis pallida) Desert hackberry, spiny hackberry Perennial Shrub Low GRASSES Plains bristlegrass, large-spike Setaria macrostachya Perennial Bunchgrass Moderate bristlegrass Sporobolus airoides Alkali sacaton Perennial Bunchgrass Moderate MESORIPARIAN TREES Acacia constricta Whitethorn Acacia Perennial shrub/small tree Low-moderate Acacia greggii Catclaw Acacia Perennial Tree Low Celtis laevigata (Celtis reticulata) Netleaf/Canyon hackberry Perennial Tree Moderate Chilopsis linearis Desert Willow Perennial Tree Moderate Parkinsonia florida Blue Palo Verde Perennial Tree Low- Moderate Populus fremontii ssp. fremontii Fremont cottonwood Perennial Tree High Prosopis pubescens Screwbean mesquite Perennial Tree Moderate Prosopis velutina Velvet mesquite Perennial Tree Low Salix gooddingii Goodding’s willow Perennial Tree High SHRUBS Anisacanthus thurberi (Drejera thurberi) Desert honeysuckle Perennial Shrub Moderate Celtis ehrenbergiana (Celtis pallida) Desert hackberry, spiny hackberry Perennial Shrub Low Lycium andersonii var. andersonii Anderson Wolfberry, water jacket Perennial Shrub Low Fremont Wolfberry, Fremont's -

List of Approved Plants

APPENDIX "X" – PLANT LISTS Appendix "X" Contains Three (3) Plant Lists: X.1. List of Approved Indigenous Plants Allowed in any Landscape Zone. X.2. List of Approved Non-Indigenous Plants Allowed ONLY in the Private Zone or Semi-Private Zone. X.3. List of Prohibited Plants Prohibited for any location on a residential Lot. X.1. LIST OF APPROVED INDIGENOUS PLANTS. Approved Indigenous Plants may be used in any of the Landscape Zones on a residential lot. ONLY approved indigenous plants may be used in the Native Zone and the Revegetation Zone for those landscape areas located beyond the perimeter footprint of the home and site walls. The density, ratios, and mix of any added indigenous plant material should approximate those found in the general area of the native undisturbed desert. Refer to Section 8.4 and 8.5 of the Design Guidelines for an explanation and illustration of the Native Zone and the Revegetation Zone. For clarity, Approved Indigenous Plants are considered those plant species that are specifically indigenous and native to Desert Mountain. While there may be several other plants that are native to the upper Sonoran Desert, this list is specific to indigenous and native plants within Desert Mountain. X.1.1. Indigenous Trees: COMMON NAME BOTANICAL NAME Blue Palo Verde Parkinsonia florida Crucifixion Thorn Canotia holacantha Desert Hackberry Celtis pallida Desert Willow / Desert Catalpa Chilopsis linearis Foothills Palo Verde Parkinsonia microphylla Net Leaf Hackberry Celtis reticulata One-Seed Juniper Juniperus monosperma Velvet Mesquite / Native Mesquite Prosopis velutina (juliflora) X.1.2. Indigenous Shrubs: COMMON NAME BOTANICAL NAME Anderson Thornbush Lycium andersonii Barberry Berberis haematocarpa Bear Grass Nolina microcarpa Brittle Bush Encelia farinosa Page X - 1 Approved - February 24, 2020 Appendix X Landscape Guidelines Bursage + Ambrosia deltoidea + Canyon Ragweed Ambrosia ambrosioides Catclaw Acacia / Wait-a-Minute Bush Acacia greggii / Senegalia greggii Catclaw Mimosa Mimosa aculeaticarpa var. -

Phoenix Active Management Area Low-Water-Use/Drought-Tolerant Plant List

Arizona Department of Water Resources Phoenix Active Management Area Low-Water-Use/Drought-Tolerant Plant List Official Regulatory List for the Phoenix Active Management Area Fourth Management Plan Arizona Department of Water Resources 1110 West Washington St. Ste. 310 Phoenix, AZ 85007 www.azwater.gov 602-771-8585 Phoenix Active Management Area Low-Water-Use/Drought-Tolerant Plant List Acknowledgements The Phoenix AMA list was prepared in 2004 by the Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR) in cooperation with the Landscape Technical Advisory Committee of the Arizona Municipal Water Users Association, comprised of experts from the Desert Botanical Garden, the Arizona Department of Transporation and various municipal, nursery and landscape specialists. ADWR extends its gratitude to the following members of the Plant List Advisory Committee for their generous contribution of time and expertise: Rita Jo Anthony, Wild Seed Judy Mielke, Logan Simpson Design John Augustine, Desert Tree Farm Terry Mikel, U of A Cooperative Extension Robyn Baker, City of Scottsdale Jo Miller, City of Glendale Louisa Ballard, ASU Arboritum Ron Moody, Dixileta Gardens Mike Barry, City of Chandler Ed Mulrean, Arid Zone Trees Richard Bond, City of Tempe Kent Newland, City of Phoenix Donna Difrancesco, City of Mesa Steve Priebe, City of Phornix Joe Ewan, Arizona State University Janet Rademacher, Mountain States Nursery Judy Gausman, AZ Landscape Contractors Assn. Rick Templeton, City of Phoenix Glenn Fahringer, Earth Care Cathy Rymer, Town of Gilbert Cheryl Goar, Arizona Nurssery Assn. Jeff Sargent, City of Peoria Mary Irish, Garden writer Mark Schalliol, ADOT Matt Johnson, U of A Desert Legum Christy Ten Eyck, Ten Eyck Landscape Architects Jeff Lee, City of Mesa Gordon Wahl, ADWR Kirti Mathura, Desert Botanical Garden Karen Young, Town of Gilbert Cover Photo: Blooming Teddy bear cholla (Cylindropuntia bigelovii) at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monutment. -

Ajo Peak to Tinajas Altas: a Flora of Southwestern Arizona. Part 20

Felger, R.S. and S. Rutman. 2016. Ajo Peak to Tinajas Altas: A Flora of Southwestern Arizona. Part 20. Eudicots: Solanaceae to Zygophyllaceae. Phytoneuron 2016-52: 1–66. Published 4 August 2016. ISSN 2153 733X AJO PEAK TO TINAJAS ALTAS: A FLORA OF SOUTHWESTERN ARIZONA PART 20. EUDICOTS: SOLANACEAE TO ZYGOPHYLLACEAE RICHARD STEPHEN FELGER Herbarium, University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 & International Sonoran Desert Alliance PO Box 687 Ajo, Arizona 85321 *Author for correspondence: [email protected] SUSAN RUTMAN 90 West 10th Street Ajo, Arizona 85321 [email protected] ABSTRACT A floristic account is provided for Solanaceae, Talinaceae, Tamaricaceae, Urticaceae, Verbenaceae, and Zygophyllaceae as part of the vascular plant flora of the contiguous protected areas of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, and the Tinajas Altas Region in southwestern Arizona—the heart of the Sonoran Desert. This account includes 40 taxa, of which about 10 taxa are represented by fossil specimens from packrat middens. This is the twentieth contribution for this flora, published in Phytoneuron and also posted open access on the website of the University of Arizona Herbarium: <http//cals.arizona.edu/herbarium/content/flora-sw-arizona>. Six eudicot families are included in this contribution (Table 1): Solanaceae (9 genera, 21 species), Talinaceae (1 species), Tamaricaceae (1 genus, 2 species), Urticaceae (2 genera, 2 species), Verbenaceae (4 genera, 7 species), and Zygophyllaceae (4 genera, 7 species). The flora area covers 5141 km 2 (1985 mi 2) of contiguous protected areas in the heart of the Sonoran Desert (Figure 1). The first article in this series includes maps and brief descriptions of the physical, biological, ecological, floristic, and deep history of the flora area (Felger et al. -

Potato Psyllid in the Pacific Northwest: a Worrisome Marriage?

Potato Progress Research & Extension for the Potato Industry of Idaho, Oregon, & Washington Andrew Jensen, Editor. [email protected]; 509-760-4859 www.nwpotatoresearch.com Volume XVI, Number 14 October 6, 2016 Matrimony vine and potato psyllid in the Pacific Northwest: a worrisome marriage? David R. Horton, Jenita Thinakaran, W. Rodney Cooper, Joseph E. Munyaneza USDA-ARS Carrie H. Wohleb, Timothy D. Waters, William E. Snyder, Zhen “Daisy” Fu, David W. Crowder Washington State University Andrew S. Jensen Northwest Potato Research Consortium Until the 2011 growing season, potato psyllid was considered to be primarily or strictly a problem in regions outside of Washington, Idaho, and Oregon. This bit of complacency is fairly understandable. Despite a history of psyllid outbreaks in North America known from at least the late 1800s, no wide-scale damage had been seen in regions of the Pacific Northwest, outside of some hotspots in southeast Idaho (Fig. 1). Indeed, the accepted wisdom in the 1900s was that potato psyllid was unable to overwinter in northern latitudes, and that outbreaks extending into Montana and similar latitudes were due to dispersal by psyllids northwards from winter and spring habitats in the southern U.S. and northern Mexico (Fig. 1). The perception that potato psyllid was not a concern in the Pacific Northwest was shattered in 2011, when an outbreak of zebra chip disease caused substantial economic damage in all three states. Five years later, we still do not know what conditions led to that outbreak. The most important question was and continues to be: what are the sources of potato psyllids that colonize potato fields in late May and early June? Not Figure 1. -

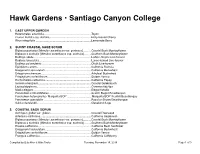

SCC Native Garden List by Community.Pages

Hawk Gardens • Santiago Canyon College 1. EAST UPPER GARDEN Heteromeles arbutifolia............................................................. Toyon Prunus ilicifolia ssp. ilicifolia...................................................... Holly-leaved Cherry Rhus integrifolia........................................................................ Lemonade Berry 2. SUNNY COASTAL SAGE SCRUB Diplacus puniceus [Mimulus aurantiacus var. puniceus]........... Coastal Bush Monkeyflower Diplacus x australis [Mimulus aurantiacus ssp. australis]......... Southern Bush Monkeyflower Dudleya edulis........................................................................... Ladies’-fingers Live-forever Dudleya lanceolata.................................................................... Lance-leaved Live-forever Dudleya pulverulenta................................................................ Chalk Live-forever Epilobium canum....................................................................... California Fuchsia Eriogonum fasciculatum............................................................ California Buckwheat Eriogonum cinereum................................................................. Ashyleaf Buckwheat Eriophyllum confertiflorum......................................................... Golden Yarrow Eschscholzia californica............................................................ California Poppy lsocoma menziesli..................................................................... Coastal Goldenbush Layia platyglossa......................................................................