Fear Reduction Jeanette E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparing the Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive

Special Issue INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND May 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Comparing the effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and treatment based on acceptance and commitment therapy on reducing anxiety and depression in women with post-traumatic stress disorder caused by the accident Najaf Abad city of Esfahan Esmaeil Mardani Zadeh MA in Clinical Psychology [email protected] Elham Yousefi MA in Clinical Psychology [email protected] Atousa Khosravi Farsani MA in Psychology Atousa [email protected] Abstract Aims Secondary trauma is a psychological consequence of direct and prolonged contact with a post-traumatic stress disorder person. The purpose of this study was to Compare the effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and treatment based on acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) on reducing anxiety and depression in women with post-traumatic stress disorder caused by the accident, with controlling the effect of depression, anxiety and stress. Methods: In this quasi-experimental research with pretest-posttest with control group design, 36 women of post-traumatic stress disorder caused by the accident referred to Modarress Psychiatric Hospital of Esfahan, Iran in 2015 were studied. The people who have attained high score on the secondary trauma test were randomly assigned to two experimental groups and one control group. The research instruments were a demographic questionnaire, questionnaire of secondary post-traumatic stress, and questionnaire of depression, anxiety and stress. The interventions (Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and acceptance commitment therapy) in the experimental group were 8 weeks and once a week, the control group did not receive any training. -

Features of the Application of Art-Therapeutic and Gaming Technology Based on Folk Music in Rehabilitation and Socialization of Children with Health Limitations

Scientific Foundation SPIROSKI, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020 Aug 15; 8(E):373-381. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2020.3588 eISSN: 1857-9655 Category: E - Public Health Section: Public Health Education and Training Features of the application of art-therapeutic and gaming technology based on folk music in rehabilitation and socialization of children with health limitations Natalia Ivanovna Anufrieva*, Aleksandr Vlavlenovich Kamenets, Marina Viktorovna Pereverzeva, Marina Gennadievna Kruglova Department of Sociology and Philosophy of Art, Russian State Social University, Wilhelm Pieck Street, 4/1, Moscow 129226, Russia Abstract Edited by: Ksenija Bogoeva-Kostovska AIM: The purpose of the work is to study the specifics and evaluate the effectiveness of the use of art-therapeutic Citation: Anufrieva NI, Kamenets AV, Pereverzeva MV, Kruglova MG. Features of the application of art- and gaming technologies based on musical folklore in the course of rehabilitation of children with health limitations. therapeutic and gaming technology based on folk music in rehabilitation and socialization of children with health MATERIALS AND METHODS: The socialization of such children depends largely on the characteristics of health, limitations. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2020 Aug 15; the principles of their training, and the effectiveness of the chosen methods. This justifies the need to analyze the 8(E):373-381. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2020.3588 *Correspondence: Natalia Ivanovna Anufrieva. practical experience and evaluate the results of efforts of specialists who deal with special children. Department of Sociology and Philosophy of Art, Russian State Social University, Wilhelm Pieck Street, 4/1, Moscow RESULTS: The results of the conducted psychological and pedagogical experiment on the use of art-therapeutic and 129226, Russia. -

Death - the Eternal Truth of Life

© 2018 JETIR March 2018, Volume 5, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) DEATH - THE ETERNAL TRUTH OF LIFE The „DEATH‟ that comes from the German word „DEAD‟ which means tot, while the word „kill‟ is toten, which literally means to make dead. Likewise in Dutch ,‟DEAD‟ is dood and “kill” is doden. In Swedish, “DEAD” is dod and „Kill‟ is doda. In English the same process resulted in the word “DEADEN”, where the suffix “EN” means “to cause to be”. We all know that the things which has life is going to be dead in future anytime any moment. So, the sentence we know popularly that “Man is mortal”. The sources of life comes into human body when he/she is in the womb of mother. The active meeting of sperm and eggs, it create a new life in the woman‟s overy, and the woman carried the foetus with 10 months and ten days to given birth of a new born baby . When the baby comes out from the pathway of the vagina of his/her mother, then his/her first cry is depicted that the new born baby is starting to adjustment of of the newly changing environment . For that very first day, the baby‟s survivation is rairtained by his/her primary environment. But the tendency of death is started also. In any time of any space the human baby have to accept death. Not only in the case of human being, but the animals, trees, species, reptailes has also the probability of death. The above mentioned live behind are also survival for the fittest. -

Psichologijos Žodynas Dictionary of Psychology

ANGLŲ–LIETUVIŲ KALBŲ PSICHOLOGIJOS ŽODYNAS ENGLISH–LITHUANIAN DICTIONARY OF PSYCHOLOGY VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETAS Albinas Bagdonas Eglė Rimkutė ANGLŲ–LIETUVIŲ KALBŲ PSICHOLOGIJOS ŽODYNAS Apie 17 000 žodžių ENGLISH–LITHUANIAN DICTIONARY OF PSYCHOLOGY About 17 000 words VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETO LEIDYKLA VILNIUS 2013 UDK 159.9(038) Ba-119 Apsvarstė ir rekomendavo išleisti Vilniaus universiteto Filosofijos fakulteto taryba (2013 m. kovo 6 d.; protokolas Nr. 2) RECENZENTAI: prof. Audronė LINIAUSKAITĖ Klaipėdos universitetas doc. Dalia NASVYTIENĖ Lietuvos edukologijos universitetas TERMINOLOGIJOS KONSULTANTĖ dr. Palmira ZEMLEVIČIŪTĖ REDAKCINĖ KOMISIJA: Albinas BAGDONAS Vida JAKUTIENĖ Birutė POCIŪTĖ Gintautas VALICKAS Žodynas parengtas įgyvendinant Europos socialinio fondo remiamą projektą „Pripažįstamos kvalifikacijos neturinčių psichologų tikslinis perkvalifikavimas pagal Vilniaus universiteto bakalauro ir magistro studijų programas – VUPSIS“ (2011 m. rugsėjo 29 d. sutartis Nr. VP1-2.3.- ŠMM-04-V-02-001/Pars-13700-2068). Pirminis žodyno variantas (1999–2010 m.) rengtas Vilniaus universiteto Specialiosios psichologijos laboratorijos lėšomis. ISBN 978-609-459-226-3 © Albinas Bagdonas, 2013 © Eglė Rimkutė, 2013 © VU Specialiosios psichologijos laboratorija, 2013 © Vilniaus universitetas, 2013 PRATARMĖ Sparčiai plėtojantis globalizacijos proce- atvejus, kai jų vertimas į lietuvių kalbą gali sams, informacinėms technologijoms, ne- kelti sunkumų), tik tam tikroms socialinėms išvengiamai didėja ir anglų kalbos, kaip ir etninėms grupėms būdingų žodžių, slengo, -

List of Phobias: Beaten by a Rod Or Instrument of Punishment, Or of # Being Severely Criticized — Rhabdophobia

Beards — Pogonophobia. List of Phobias: Beaten by a rod or instrument of punishment, or of # being severely criticized — Rhabdophobia. Beautiful women — Caligynephobia. 13, number — Triskadekaphobia. Beds or going to bed — Clinophobia. 8, number — Octophobia. Bees — Apiphobia or Melissophobia. Bicycles — Cyclophobia. A Birds — Ornithophobia. Abuse, sexual — Contreltophobia. Black — Melanophobia. Accidents — Dystychiphobia. Blindness in a visual field — Scotomaphobia. Air — Anemophobia. Blood — Hemophobia, Hemaphobia or Air swallowing — Aerophobia. Hematophobia. Airborne noxious substances — Aerophobia. Blushing or the color red — Erythrophobia, Airsickness — Aeronausiphobia. Erytophobia or Ereuthophobia. Alcohol — Methyphobia or Potophobia. Body odors — Osmophobia or Osphresiophobia. Alone, being — Autophobia or Monophobia. Body, things to the left side of the body — Alone, being or solitude — Isolophobia. Levophobia. Amnesia — Amnesiphobia. Body, things to the right side of the body — Anger — Angrophobia or Cholerophobia. Dextrophobia. Angina — Anginophobia. Bogeyman or bogies — Bogyphobia. Animals — Zoophobia. Bolsheviks — Bolshephobia. Animals, skins of or fur — Doraphobia. Books — Bibliophobia. Animals, wild — Agrizoophobia. Bound or tied up — Merinthophobia. Ants — Myrmecophobia. Bowel movements, painful — Defecaloesiophobia. Anything new — Neophobia. Brain disease — Meningitophobia. Asymmetrical things — Asymmetriphobia Bridges or of crossing them — Gephyrophobia. Atomic Explosions — Atomosophobia. Buildings, being close to high -

Author Study Tips a Chapter 22: Psychiatry the Combining Form Psych/O, Meaning Mind, Is a Useful Word Part. One Finds This Combi

Author Study Tips A Chapter 22: Psychiatry The combining form psych/o, meaning mind, is a useful word part. One finds this combining form in many interesting terms. In Greek mythology, Psyche was a young woman who loved and was loved by Eros (god of love and the son of Aphrodite). She was united with him after Aphrodite's jealousy was overcome. Psyche became the personification of the soul (the vital principle in humans related to thought, action, and emotion). The term psychedelic means characterized by hallucinations, altered perceptions, and awareness. A psychedelic is a drug, such as LSD or mescaline, which produces such effects (Greek deloun means to make visible). Here are other terms using the combining form psych/o. Psychic trauma is an emotional shock or injury that produces a lasting impression, especially on the subconscious mind. Causes of psychic trauma may be abuse or neglect in childhood. Psychotherapeutic sessions can help alleviate such psychic trauma. Psychoactive substances are drugs or other agents that affect mood, behavior, or thinking processes. Cannabis, commonly known as marijuana, is a psychoactive substance. Examples of other psychoactive substances are stimulants, such as amphetamines or speed, and sedatives, such as phenobarbital and Valium. Psychotropic medications are prescribed to treat a variety of mental illnesses (troph/o means to turn). Examples of psychotropic drugs are antianxiety and antipanic agents, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, hypnotics, and powerful antipsychotic or neuroleptic medications. Neuroleptic drugs such as phenothiazines treat symptoms of psychoses. The delusions and hallucinations of a patient with schizophrenia are treated with neuroleptic drugs such as Thorazine or Haldol. -

AVAILABLE from ABSTRACT DOCUMENT RESUME Mental

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 431 981 CG 029 333 TITLE Mental Health in Schools: New Roles for School Nurses. Addressing Barriers to Student Learning. INSTITUTION California Univ., Los Angeles. Center for Mental Health in Schools. SPONS AGENCY Health Resources and Services Administration (DHHS/PHS), Washington, DC. Maternal and Child Health Bureau. PUB DATE 1997-04-00 NOTE 298p. AVAILABLE FROM School Mental Health Project, Center for Mental Health in Schools, Dept. of Psychology, UCLA, 405 Hilgard Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90095-1563; Tel: 310-825-3634; Fax: 310-206-8716; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://smhp.psych.ucla.edu (minimal fee to cover copying, postage and handling). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Confidentiality; Due Process; Elementary Secondary Education; *Mental Health; Prevention; *Professional Development; *School Nurses; *Staff Role; Student Development IDENTIFIERS Consent; Screening Programs ABSTRACT This set of three continuing education units is designed to be used as a professional development tool for school nurses. Each unit consists of several sections designed to stand alone. Thus, the total set can be used and taught in a straightforward sequence, or one or more units and sections can be combined into a personalized course. Each section begins with specific objectives and focusing questions to guide reading and review. Interspersed throughout each section is boxed information designed to help the learner think in greater depth about the material. Test questions are provided at the end of each section as an additional study aid. Unit 1, "Placing Mental Health into the Context of Schools and the 21st Century," provides an overview and discusses enhancing health development; addressing barriers to learning; moving toward a comprehensive approach; and responding to students' problems. -

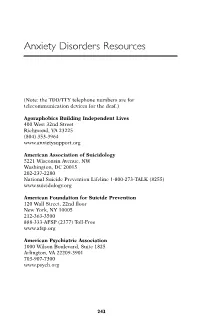

Anxiety Disorders Resources

Anxiety Disorders Resources (Note: the TDD/TTY telephone numbers are for telecommunication devices for the deaf.) Agoraphobics Building Independent Lives 400 West 32nd Street Richmond, VA 23225 (804) 353-3964 www.anxietysupport.org American Association of Suicidology 5221 Wisconsin Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20015 202-237-2280 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-TALK (8255) www.suicidology.org American Foundation for Suicide Prevention 120 Wall Street, 22nd floor New York, NY 10005 212-363-3500 888-333-AFSP (2377) Toll-Free www.afsp.org American Psychiatric Association 1000 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 1825 Arlington, VA 22209-3901 703-907-7300 www.psych.org 243 244 ANXIETY DISORDERS RESOURCES American Psychological Association 750 First Street, N.E. Washington, DC 20002-4242 800-374-2721 202-336-5500 TDD/TTY: 202-336-6213 www.apa.org Anxiety Disorders Association of America 8730 Georgia Avenue, Suite 600 Silver Spring, MD 20910 240-485-1001 www.adaa.org Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies 305 Seventh Avenue, 16th floor New York, NY 10001 (212) 647-1890 www.aabt.org Doctors Guide www.docguide.com Freedom from Fear 308 Seaview Avenue Staten Island, NY 10305 718-351-1717 www.freedomfromfear.org International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 60 Revere Drive, Suite 500 Northbrook IL 60062 847-480-9028 www.istss.org MedlinePlus: Health Information www.medlineplus.gov Mental Health America (formerly National Mental Health Association) 2000 N. Beauregard St., 6t floor Alexandria, VA 22311 800-969-6MHA (6642) 703-684-7722 TTY: 800-433-5959 www.mentalhealthamerica.net ANXIETY DISORDERS RESOURCES 245 National Alliance for the Mentally Ill Colonial Place Three 2107 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22201-3042 800-950-NAMI (6264) 703-524-7600 TDD: 703-516-7227 www.nami.org National Anxiety Foundation 3135 Custer Drive Lexington, KY 40517-4001 606-272-7166 National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder U.S. -

Comparative Evolutionary Thanatology of Grief, with Special Reference to Nonhuman Primates

Comparative Evolutionary Thanatology of Grief, with Special Reference to Nonhuman Primates James R. Anderson Kyoto University Abstract: The impact of the dead on the living is considered from an evolutionary comparative perspective. After a brief review of young children’s developing understanding of the concept of death, the interest of looking at how other species respond to dying and dead individuals is introduced. Solutions to managing dead individuals in social insect communities are described, highlighting evolutionarily ancient, effective behavioral mechanisms that most likely function with no emotional component. I then review examples of responses to dying and dead individuals in nonhuman primates, with particular reference to continued transport and caretaking of dead infants, responses to traumatic deaths in wild populations of monkeys and apes, and a detailed case report of the peaceful death of an old female chimpanzee surrounded by members of her group. The emotional correlates of primates’ reactions to bereavement are discussed, and some suggested evolutionarily shared responses to the dead are proposed. Key words: thanatology, death, dying, emotions, social insects, nonhuman primates, chimpanzees Thanatology can be broadly defined as the study of death and dying, and researchers from a wide range of disciplines are thanatologists. Among others, studies in medicine, biology, psychology, anthropology, palaeontology, sociology and philosophy all contribute new knowledge about the antecedents, causes, and consequences of death (e.g. Exley 2004; Haldane 2007; Klarsfeld et al. 2003; Kübler-Ross 1969; Pettitt 2011; Powner et al. 1996). Concerning people’s understanding of death, psychologists generally agree that the typical human adult’s concept of death comprises at least four sub-concepts or “components” (Speece 1995). -

Cultural Geographies

Cultural Geographies http://cgj.sagepub.com/ Ecological anxiety disorder: diagnosing the politics of the Anthropocene Paul Robbins and Sarah A. Moore Cultural Geographies 2013 20: 3 DOI: 10.1177/1474474012469887 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cgj.sagepub.com/content/20/1/3 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Cultural Geographies can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cgj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cgj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Jan 7, 2013 What is This? Downloaded from cgj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN on January 14, 2013 CGJ20110.1177/1474474012469887Cultural geographiesRobbins and Moore 4698872012 Article cultural geographies 20(1) 3 –19 Ecological anxiety disorder: © The Author(s) 2012 Reprints and permission: sagepub. co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav diagnosing the politics of the DOI: 10.1177/1474474012469887 Anthropocene cgj.sagepub.com Paul Robbins University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA Sarah A. Moore University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA Abstract The quickly changing character of the global environment has predicated a number of crises in the sciences of biology and ecology. Specifically, the rapid rate of ecological change has led to the proliferation of novel ecologies. These unprecedented ecosystems and assemblages challenge the scientific, as well as cultural, core of many disciplines. This has led to divisive debates over what constitutes a ‘natural’ system state, and over what kinds of interventions, if any, should be advocated by scientists. In this paper, we review the nature of the recent discomfort, conflict, and ambivalence experienced in some sciences. -

Catherine A. Wright

In the Darkness Grows the Green: The Promise of a New Cosmological Horizon of Meaning Within a Critical Inquiry of Human Suffering and the Cross by Catherine A. Wright A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Regis College and the Theology Department of the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael's College © Copyright by Catherine A. Wright 2015 In The Darkness Grows the Green: The Promise of a New Cosmological Horizon of Meaning Within a Critical Inquiry of Human Suffering and the Cross Catherine A. Wright Doctor of Philosophy in Theology Regis College and the University of St. Michael’s College 2015 Abstract Humans have been called “mud of the earth,”i organic stardust animated by the Ruah of our Creator,ii and microcosms of the macrocosm.iii Since we now understand in captivating detail how humanity has emerged from the cosmos, then we must awaken to how humanity is “of the earth” in all the magnificence and brokenness that this entails. This thesis will demonstrate that there are no easy answers nor complete theological systems to derive satisfying answers to the mystery of human suffering. Rather, this thesis will uncover aspects of sacred revelation offered in and through creation that could mould distinct biospiritual human imaginations and cultivate the Earth literacy required to construct an ecological theological anthropology (ETA). It is this ecocentric interpretive framework that could serve as vital sustenance and a vision of hope for transformation when suffering befalls us. -

List of Phobias and Simple Cures.Pdf

Phobia This article is about the clinical psychology. For other uses, see Phobia (disambiguation). A phobia (from the Greek: φόβος, Phóbos, meaning "fear" or "morbid fear") is, when used in the context of clinical psychology, a type of anxiety disorder, usually defined as a persistent fear of an object or situation in which the sufferer commits to great lengths in avoiding, typically disproportional to the actual danger posed, often being recognized as irrational. In the event the phobia cannot be avoided entirely the sufferer will endure the situation or object with marked distress and significant interference in social or occupational activities.[1] The terms distress and impairment as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR) should also take into account the context of the sufferer's environment if attempting a diagnosis. The DSM-IV-TR states that if a phobic stimulus, whether it be an object or a social situation, is absent entirely in an environment - a diagnosis cannot be made. An example of this situation would be an individual who has a fear of mice (Suriphobia) but lives in an area devoid of mice. Even though the concept of mice causes marked distress and impairment within the individual, because the individual does not encounter mice in the environment no actual distress or impairment is ever experienced. Proximity and the degree to which escape from the phobic stimulus should also be considered. As the sufferer approaches a phobic stimulus, anxiety levels increase (e.g. as one gets closer to a snake, fear increases in ophidiophobia), and the degree to which escape of the phobic stimulus is limited and has the effect of varying the intensity of fear in instances such as riding an elevator (e.g.