Comparing the Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Features of the Application of Art-Therapeutic and Gaming Technology Based on Folk Music in Rehabilitation and Socialization of Children with Health Limitations

Scientific Foundation SPIROSKI, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020 Aug 15; 8(E):373-381. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2020.3588 eISSN: 1857-9655 Category: E - Public Health Section: Public Health Education and Training Features of the application of art-therapeutic and gaming technology based on folk music in rehabilitation and socialization of children with health limitations Natalia Ivanovna Anufrieva*, Aleksandr Vlavlenovich Kamenets, Marina Viktorovna Pereverzeva, Marina Gennadievna Kruglova Department of Sociology and Philosophy of Art, Russian State Social University, Wilhelm Pieck Street, 4/1, Moscow 129226, Russia Abstract Edited by: Ksenija Bogoeva-Kostovska AIM: The purpose of the work is to study the specifics and evaluate the effectiveness of the use of art-therapeutic Citation: Anufrieva NI, Kamenets AV, Pereverzeva MV, Kruglova MG. Features of the application of art- and gaming technologies based on musical folklore in the course of rehabilitation of children with health limitations. therapeutic and gaming technology based on folk music in rehabilitation and socialization of children with health MATERIALS AND METHODS: The socialization of such children depends largely on the characteristics of health, limitations. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2020 Aug 15; the principles of their training, and the effectiveness of the chosen methods. This justifies the need to analyze the 8(E):373-381. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2020.3588 *Correspondence: Natalia Ivanovna Anufrieva. practical experience and evaluate the results of efforts of specialists who deal with special children. Department of Sociology and Philosophy of Art, Russian State Social University, Wilhelm Pieck Street, 4/1, Moscow RESULTS: The results of the conducted psychological and pedagogical experiment on the use of art-therapeutic and 129226, Russia. -

Psichologijos Žodynas Dictionary of Psychology

ANGLŲ–LIETUVIŲ KALBŲ PSICHOLOGIJOS ŽODYNAS ENGLISH–LITHUANIAN DICTIONARY OF PSYCHOLOGY VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETAS Albinas Bagdonas Eglė Rimkutė ANGLŲ–LIETUVIŲ KALBŲ PSICHOLOGIJOS ŽODYNAS Apie 17 000 žodžių ENGLISH–LITHUANIAN DICTIONARY OF PSYCHOLOGY About 17 000 words VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETO LEIDYKLA VILNIUS 2013 UDK 159.9(038) Ba-119 Apsvarstė ir rekomendavo išleisti Vilniaus universiteto Filosofijos fakulteto taryba (2013 m. kovo 6 d.; protokolas Nr. 2) RECENZENTAI: prof. Audronė LINIAUSKAITĖ Klaipėdos universitetas doc. Dalia NASVYTIENĖ Lietuvos edukologijos universitetas TERMINOLOGIJOS KONSULTANTĖ dr. Palmira ZEMLEVIČIŪTĖ REDAKCINĖ KOMISIJA: Albinas BAGDONAS Vida JAKUTIENĖ Birutė POCIŪTĖ Gintautas VALICKAS Žodynas parengtas įgyvendinant Europos socialinio fondo remiamą projektą „Pripažįstamos kvalifikacijos neturinčių psichologų tikslinis perkvalifikavimas pagal Vilniaus universiteto bakalauro ir magistro studijų programas – VUPSIS“ (2011 m. rugsėjo 29 d. sutartis Nr. VP1-2.3.- ŠMM-04-V-02-001/Pars-13700-2068). Pirminis žodyno variantas (1999–2010 m.) rengtas Vilniaus universiteto Specialiosios psichologijos laboratorijos lėšomis. ISBN 978-609-459-226-3 © Albinas Bagdonas, 2013 © Eglė Rimkutė, 2013 © VU Specialiosios psichologijos laboratorija, 2013 © Vilniaus universitetas, 2013 PRATARMĖ Sparčiai plėtojantis globalizacijos proce- atvejus, kai jų vertimas į lietuvių kalbą gali sams, informacinėms technologijoms, ne- kelti sunkumų), tik tam tikroms socialinėms išvengiamai didėja ir anglų kalbos, kaip ir etninėms grupėms būdingų žodžių, slengo, -

AVAILABLE from ABSTRACT DOCUMENT RESUME Mental

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 431 981 CG 029 333 TITLE Mental Health in Schools: New Roles for School Nurses. Addressing Barriers to Student Learning. INSTITUTION California Univ., Los Angeles. Center for Mental Health in Schools. SPONS AGENCY Health Resources and Services Administration (DHHS/PHS), Washington, DC. Maternal and Child Health Bureau. PUB DATE 1997-04-00 NOTE 298p. AVAILABLE FROM School Mental Health Project, Center for Mental Health in Schools, Dept. of Psychology, UCLA, 405 Hilgard Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90095-1563; Tel: 310-825-3634; Fax: 310-206-8716; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://smhp.psych.ucla.edu (minimal fee to cover copying, postage and handling). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Confidentiality; Due Process; Elementary Secondary Education; *Mental Health; Prevention; *Professional Development; *School Nurses; *Staff Role; Student Development IDENTIFIERS Consent; Screening Programs ABSTRACT This set of three continuing education units is designed to be used as a professional development tool for school nurses. Each unit consists of several sections designed to stand alone. Thus, the total set can be used and taught in a straightforward sequence, or one or more units and sections can be combined into a personalized course. Each section begins with specific objectives and focusing questions to guide reading and review. Interspersed throughout each section is boxed information designed to help the learner think in greater depth about the material. Test questions are provided at the end of each section as an additional study aid. Unit 1, "Placing Mental Health into the Context of Schools and the 21st Century," provides an overview and discusses enhancing health development; addressing barriers to learning; moving toward a comprehensive approach; and responding to students' problems. -

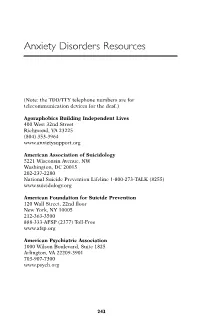

Anxiety Disorders Resources

Anxiety Disorders Resources (Note: the TDD/TTY telephone numbers are for telecommunication devices for the deaf.) Agoraphobics Building Independent Lives 400 West 32nd Street Richmond, VA 23225 (804) 353-3964 www.anxietysupport.org American Association of Suicidology 5221 Wisconsin Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20015 202-237-2280 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-TALK (8255) www.suicidology.org American Foundation for Suicide Prevention 120 Wall Street, 22nd floor New York, NY 10005 212-363-3500 888-333-AFSP (2377) Toll-Free www.afsp.org American Psychiatric Association 1000 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 1825 Arlington, VA 22209-3901 703-907-7300 www.psych.org 243 244 ANXIETY DISORDERS RESOURCES American Psychological Association 750 First Street, N.E. Washington, DC 20002-4242 800-374-2721 202-336-5500 TDD/TTY: 202-336-6213 www.apa.org Anxiety Disorders Association of America 8730 Georgia Avenue, Suite 600 Silver Spring, MD 20910 240-485-1001 www.adaa.org Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies 305 Seventh Avenue, 16th floor New York, NY 10001 (212) 647-1890 www.aabt.org Doctors Guide www.docguide.com Freedom from Fear 308 Seaview Avenue Staten Island, NY 10305 718-351-1717 www.freedomfromfear.org International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 60 Revere Drive, Suite 500 Northbrook IL 60062 847-480-9028 www.istss.org MedlinePlus: Health Information www.medlineplus.gov Mental Health America (formerly National Mental Health Association) 2000 N. Beauregard St., 6t floor Alexandria, VA 22311 800-969-6MHA (6642) 703-684-7722 TTY: 800-433-5959 www.mentalhealthamerica.net ANXIETY DISORDERS RESOURCES 245 National Alliance for the Mentally Ill Colonial Place Three 2107 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22201-3042 800-950-NAMI (6264) 703-524-7600 TDD: 703-516-7227 www.nami.org National Anxiety Foundation 3135 Custer Drive Lexington, KY 40517-4001 606-272-7166 National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder U.S. -

Cultural Geographies

Cultural Geographies http://cgj.sagepub.com/ Ecological anxiety disorder: diagnosing the politics of the Anthropocene Paul Robbins and Sarah A. Moore Cultural Geographies 2013 20: 3 DOI: 10.1177/1474474012469887 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cgj.sagepub.com/content/20/1/3 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Cultural Geographies can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cgj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cgj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Jan 7, 2013 What is This? Downloaded from cgj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN on January 14, 2013 CGJ20110.1177/1474474012469887Cultural geographiesRobbins and Moore 4698872012 Article cultural geographies 20(1) 3 –19 Ecological anxiety disorder: © The Author(s) 2012 Reprints and permission: sagepub. co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav diagnosing the politics of the DOI: 10.1177/1474474012469887 Anthropocene cgj.sagepub.com Paul Robbins University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA Sarah A. Moore University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA Abstract The quickly changing character of the global environment has predicated a number of crises in the sciences of biology and ecology. Specifically, the rapid rate of ecological change has led to the proliferation of novel ecologies. These unprecedented ecosystems and assemblages challenge the scientific, as well as cultural, core of many disciplines. This has led to divisive debates over what constitutes a ‘natural’ system state, and over what kinds of interventions, if any, should be advocated by scientists. In this paper, we review the nature of the recent discomfort, conflict, and ambivalence experienced in some sciences. -

Paranoid – Suspicious; Argumentative; Paranoid; Continually on the Lookout for Trickery and Abuse; Jealous; Tendency to Blame Others; Cold and Humorless

Personality Disturbance Gathering, nr.49 (key to possible disturbances) Every person may be used only once, except “by proxy” will overlap another person/condition, and there is one condition which will not be assigned to characters. 1. Agoraphobia – Fear of being out in the open or in public places; nervous; anxious 2. Autophobia/Monophobia – Extreme dislike or anger of oneself, or of an ethnic group from which one descends. 3. Anti-Social Personality Disorder – Failure to conform to societal norms; lack of remorse or indifferent; impulsivity or failure to plan ahead; consistent irresponsibility; deceitfulness. 4. Avoidant Personality Disorder – Socially awkward; fear of criticism, disapproval or rejection; views self as socially inept; reluctant to take personal risks or to engage in new activities because they may prove embarrassing. 5. Body Dysmorphic Disorder – A perceived defect of oneself. 6. Borderline – Very unstable relationships; erratic emotions; self-damaging behavior; impulsive; unpredictable aggressive and sexual behavior; sometimes similar to Autophobia/Monophobia; easily angered. 7. Brief Psychotic Disorder – Delusions, hallucination, disorganized speech or catatonic behavior which last between one and four weeks. 8. “…by Proxy” – Any condition where someone uses another (adult, children) to achieve their needs. 9. Cognitive Dissonance – the wrestling with opposing viewpoints in our mind, and determine which decision to make; our effort to fundamentally strive for harmony in our thinking. 10. Compulsive – Perfectionists, preoccupied with details, rules and schedules; more concerned about work than pleasure; serious and formal; cannot express tender feelings. 11. Compulsive Hoarding – Excessive acquisition of possessions, and failure to use or discard them, even if the items are worthless, hazardous or unsanitary. -

Frankenstein Or Prometheus: an Investigation in Essentialism of Medical Technology Mehdi Moinzadeh, Sepideh Motamedi

International Journal of ody, Mind & Culture Cross-Cultural, Interdisciplinary Health Studies Information for Authors AIM AND SCOPE managers and therapists to make more Modern medicine is thought to be in a integrative decisions. paradigmatic crisis in terms of the accelerative STUDY DESIGN demographic, epidemiologic, social, and We advise authors to design studies based on the discursive aspects. The ontological, appropriate guidelines. In randomized epistemological, and methodological gaps in controlled trials, the CONSORT guideline biomedicine lead to a chaotic condition in (www.consort-statement.org/consort-statement ), health beliefs and behaviors. The International in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, the Journal of Body, Mind and Culture (IJBMC) is an PRISMA (formally QUOROM) guideline international, peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary (www.prisma-statement.org ), in studies of medical journal and a fully “online first” diagnostic accuracy, the STARD guideline publication focused on interdisciplinary, cross- (www.stard-statement.org ), in observational cultural, and conceptual research. The studies in epidemiology, the STROBE researches should focus on paradigmatic shift guideline ( www.strobe-statement.org ), and in and/or humanizing medical practice. meta-analyses of observational studies in All interdisciplinary researches, such as epidemiology, the MOOSE guideline social sciences (e.g., sociology, anthropology, (www.consort-statement.org/index.aspx?o=1347 ) and psychology), humanities (e.g., literature, should be used. religion, history, and philosophy), and arts (e.g., music and cinema), which have an impact HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS on medical education and practice, are Researches involving human beings or animals acceptable. must adhere to the principles of the The IJBMC team is based mainly in Germany Declaration of Helsinki and Iran, although we also have editors (www.wma.net/e/ethicsunit/helsinki.htm ). -

Psychopathology-Madjirova.Pdf

NADEJDA PETROVA MADJIROVA PSYCHOPATHOLOGY psychophysiological and clinical aspects PLOVDIV 2005 I devote this book to all my patients that shared with me their intimate problems. © Nadejda Petrova Madjirova, 2015 PSYCHOPATHOLOGY: PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGICAL AND CLINICAL ASPECTS Prof. Dr. Nadejda Petrova Madjirova, MD, PhD, DMSs Reviewer: Prof. Rumen Ivandv Stamatov, PhD, DPS Prof. Drozdstoj Stoyanov Stoyanov, PhD, MD Design: Nadejda P. Madjirova, MD, PhD, DMSc. Prepress: Galya Gerasimova Printed by ISBN I. COMMON ASPECTS IN PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGY “A wise man ought to realize that health is his most valuable possession” Hippocrates C O N T E N T S I. Common aspects in psychophysiology. ..................................................1 1. Some aspects on brain structure. ....................................................5 2. Lateralisation of the brain hemispheres. ..........................................7 II. Experimental Psychology. ..................................................................... 11 1. Ivan Petrovich Pavlov. .................................................................... 11 2. John Watson’s experiments with little Albert. .................................15 III. Psychic spheres. ...................................................................................20 1. Perception – disturbances..............................................................21 2. Disturbances of Will .......................................................................40 3. Emotions ........................................................................................49 -

Name, a Novel

NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubu editions 2004 Name, A Novel Toadex Hobogrammathon Cover Ilustration: “Psycles”, Excerpts from The Bikeriders, Danny Lyon' book about the Chicago Outlaws motorcycle club. Printed in Aspen 4: The McLuhan Issue. Thefull text can be accessed in UbuWeb’s Aspen archive: ubu.com/aspen. /ubueditions ubu.com Series Editor: Brian Kim Stefans ©2004 /ubueditions NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubueditions 2004 name, a novel toadex hobogrammathon ade Foreskin stepped off the plank. The smell of turbid waters struck him, as though fro afar, and he thought of Spain, medallions, and cork. How long had it been, sussing reader, since J he had been in Spain with all those corkoid Spanish medallions, granted him by Generalissimo Hieronimo Susstro? Thirty, thirty-three years? Or maybe eighty-seven? Anyhow, as he slipped a whip clap down, he thought he might greet REVERSE BLOOD NUT 1, if only he could clear a wasp. And the plank was homely. After greeting a flock of fried antlers at the shevroad tuesday plied canticle massacre with a flash of blessed venom, he had been inter- viewed, but briefly, by the skinny wench of a woman. But now he was in Rio, fresh of a plank and trying to catch some asscheeks before heading on to Remorse. I first came in the twilight of the Soviet. Swigging some muck, and lampreys, like a bad dram in a Soviet plezhvadya dish, licking an anagram off my hands so the ——— woundn’t foust a stiff trinket up me. So that the Soviets would find out. -

Fear Reduction Jeanette E

Cardinal Stritch University Stritch Shares Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects 1-1-1979 Fear reduction Jeanette E. Coleman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.stritch.edu/etd Part of the Special Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Coleman, Jeanette E., "Fear reduction" (1979). Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects. 553. https://digitalcommons.stritch.edu/etd/553 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by Stritch Shares. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Stritch Shares. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FEAR REDUCTION by Jeanette E. Coleman A RESEARCH PAPER Submitted in PARTIAL FULFILLMENT of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Education (Education of Learning Disabled Children) at the Cardinal Stritch College Milwaukee, Wisconsin 1979 Fear Reduction This research paper has been approved for the Graduate Committee of the Cardinal Stritch College by Fear Reduction i i Table of Contents Acknowledgments i i i Chapter I Introduction A. Definitions 2 B. Scope and limitations 3 C. Summary 4 Chapter II Review of Research 4 A. I nt rod uc t ion 4 B. Anxiety 5 c. Basic elements of systematic 6 desensitization D. Hierarchies 9 E. Implementation 10 F. Examples 11 G. School phobia 14 H. Modifications 18 Chapter Ill Summary 20 References 22 Appendixes A. Relaxation technique 26 B. list of phobias 29 Fear Reduction i i i Acknowledgments My gratitude goes to: Sister Johanna Flanagan who touched my 1 ife in a very special way. -

Multi-Discipline Review

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 209500Orig1s000 MULTI-DISCIPLINE REVIEW Summary Review Office Director Cross Discipline Team Leader Review Clinical Review Non-Clinical Review Statistical Review Clinical Pharmacology Review NDA 209500 Multi-disciplinary Review and Evaluation Caplyta (lumateperone) NDA/BLA Multi-Disciplinary Review and Evaluation Application Type NDA Application Number(s) 209500 Priority or Standard Standard Submit Date(s) September 27, 2018 Received Date(s) September 27, 2018 PDUFA Goal Date December 27, 2019 Division/Office Division of Psychiatry / Office of Drug Evaluation-I Review Completion Date December 20, 2019 Established/Proper Name Lumateperone (Proposed) Trade Name Caplyta Pharmacologic Class Atypical Antipsychotic Code name ITI-007 Applicant Intra-Cellular Therapies, Inc. Dosage form 42 mg Capsules Applicant proposed Dosing 42 mg by mouth once daily Regimen Applicant Proposed Schizophrenia/Adults Indication(s)/Population(s) Applicant Proposed 58214004 | Schizophrenia (disorder) SNOMED CT Indication Disease Term for each Proposed Indication Recommendation on Approval Regulatory Action Recommended Schizophrenia/Adults Indication(s)/Population(s) (if applicable) Recommended SNOMED 58214004 | Schizophrenia (disorder) CT Indication Disease Term for each Indication (if applicable) Recommended Dosing 42 mg by mouth once daily Regimen 1 Version date: October 12, 2018 Reference ID: 4537404 NDA 209500 Multi-disciplinary Review and Evaluation Caplyta (lumateperone) Table of Contents Table of -

International Journal of Molecular Sciences

MOL2NET, 2020, 6, ISSN: 2624-5078 1 http://sciforum.net/conference/mol2net-06 MOL2NET, International Conference Series on Multidisciplinary Sciences MDPI BIOMEDIT-01; BioMedical & Information Technologies Worldwide Workshop, Chengdu, China, 2020 Research On The Signal Mining Of Adverse Events Of Montelukast Sodium Based On FAERS CHEN Lia,b,c, Javier Meana c, Bairong Shen d a Deparment of pharmacy/evidence-based pharmacy center, West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, 610041, Chengdu, Sichuan, China b Key Laboratory of Birth Defects and Related Diseases of Women and Children, Sichuan University, Ministry of Education, 610041, Chengdu, Sichuan, China c University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU, 48940, Leioa, Biscay, Basque Country, Spain d Institutes for Systems Genetics, Frontiers Science Center for Disease-related Molecular Network, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, 610041, Sichuan, China Graphical Abstract Abstract. Objective To conduct data-mining of montelukast-related adverse events after marketing to provide a reference for safe clinical medication. Methods We use reporting odds ratio (ROR) and proportional reporting ratio (PRR) methods to mine the adverse reaction signals of montelukast on the adverse reaction report data of 22 quarters from 2015Q1 to 2020Q2, extracted from the FAERS database. Results Totally 467 signals were detected with ROR and PRR, and the most relevant 50 preferred terms are conducted based on the signal strength and signal frequency, 55.32% of signals were not reported in the proved label. Adverse reaction signals of montelukast involve 27 systems and organs, in addition to psychiatric diseases, majority of adverse events included respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders and examination. Conclusion Clinical use of montelukast should pay attention to the patient's neuropsychiatric symptoms, especially those not reported in the proved label, such as MOL2NET, 2020, 6, ISSN: 2624-5078 2 http://sciforum.net/conference/mol2net-06 Separation anxiety disorder, Sleep terror and PANDAS.