Chapter 16: Psychological Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S15 Structural Pest Control, Category 7E, Pesticide Application Training

PESTICIDE APPLICATION TRAINING Category 7E Structural Pest Control Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service 2 Table of Contents Integrated Pest Management in Structures 4 Pests Usually Reproducing Indoors 6 Cockroaches 6 Cockroach control 8 Silverfish and firebrats 10 Pests of stored food 12 Fabric pests 15 Occasional Invaders 19 Pests Annoying or Attacking People and Pets 29 Common flies in buildings 29 Spiders 31 Scorpions 34 Fleas 35 Ticks 36 Bed bug, bat bug and bird bugs 39 Wasps, bees and ants 40 Entomophobia 49 Fumigation 52 Types of fumigants 55 Preparation for fumigation 59 Application and post application 61 Safe use of fumigants 62 Vertebrate Pests 65 Birds 65 Rats and mice 70 Bats 77 Skunks 78 Tree squirrels 79 Raccoons 80 Directions for using this manual This is a self-teaching manual. At the end of each major section is a list of study questions to check your understanding of the subject matter. By each question in parenthesis is the page number on which the answer to that question can be found. This will help you in checking your answers. These study questions are representative of the type that are on the cer- tification examination. By reading this manual and answering the study questions, you should be able to gain sufficient knowledge to pass the Kansas Commercial Pesticide Applicators Certification examination. 3 Integrated Pest The prescription should include not Management in only what can be done for the cus- Insect pest management in struc- tomer, but also what the customer can Structures tures involves five basic steps: do in the way of habitat removal and 1. -

Delusions of Parasitosis; an Irrational Fear of Insects Explained

FACT SHEET DELUSORY PARASITOSIS. THE BELIEF OF BEING LIVED ON BY ARTHROPODS OR OTHER ORGANISMS. Guide for Health Departments, Medical Communities, and Pest Management Professionals Dr. Gale E. Ridge Department of Entomology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Introduction Delusory parasitosis, an unshakable belief or syndrome (Hopkinson 1970) of being attacked by insects, is a very difficult and under-diagnosed condition. It often starts with an actual event or medical condition (the trigger) that may progress over time into mental illness. For those who have had the problem over long time periods, the condition can sometimes consume a person’s life. Although patients may repeatedly seek help from experts, they may refuse to abandon their ideas for test results which contradict their invested beliefs (Sneddon 1983). Sufferers can become antagonistic and relentless in their need to find someone who will confirm their self-diagnoses (Murray and Ash 2004). Those with the obsession, often search the internet, finding web-sites that support their fears. Often under the falsehood of medical authority, some of these sites provide misguided advice and inaccurate information. Poorly informed misdiagnoses by medical professionals may also contribute to the problem. This is a very complex and difficult condition to manage, requiring dedication and time by trained professionals or an interdisciplinary team of experts. Naming the syndrome Because delusory parasitosis (DP) is medically amorphous, several medical specialists have been involved, e.g., psychiatrists, physicians, dermatologists, and medical entomologists. All have tried to define the condition. The term delusions of parasitosis was coined by Wilson and Miller (1946) dispelling earlier use of the words acarophobia (Thibierge 1894), entomophobia, and parasitophobia. -

Comparing the Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive

Special Issue INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND May 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Comparing the effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and treatment based on acceptance and commitment therapy on reducing anxiety and depression in women with post-traumatic stress disorder caused by the accident Najaf Abad city of Esfahan Esmaeil Mardani Zadeh MA in Clinical Psychology [email protected] Elham Yousefi MA in Clinical Psychology [email protected] Atousa Khosravi Farsani MA in Psychology Atousa [email protected] Abstract Aims Secondary trauma is a psychological consequence of direct and prolonged contact with a post-traumatic stress disorder person. The purpose of this study was to Compare the effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and treatment based on acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) on reducing anxiety and depression in women with post-traumatic stress disorder caused by the accident, with controlling the effect of depression, anxiety and stress. Methods: In this quasi-experimental research with pretest-posttest with control group design, 36 women of post-traumatic stress disorder caused by the accident referred to Modarress Psychiatric Hospital of Esfahan, Iran in 2015 were studied. The people who have attained high score on the secondary trauma test were randomly assigned to two experimental groups and one control group. The research instruments were a demographic questionnaire, questionnaire of secondary post-traumatic stress, and questionnaire of depression, anxiety and stress. The interventions (Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and acceptance commitment therapy) in the experimental group were 8 weeks and once a week, the control group did not receive any training. -

Features of the Application of Art-Therapeutic and Gaming Technology Based on Folk Music in Rehabilitation and Socialization of Children with Health Limitations

Scientific Foundation SPIROSKI, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020 Aug 15; 8(E):373-381. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2020.3588 eISSN: 1857-9655 Category: E - Public Health Section: Public Health Education and Training Features of the application of art-therapeutic and gaming technology based on folk music in rehabilitation and socialization of children with health limitations Natalia Ivanovna Anufrieva*, Aleksandr Vlavlenovich Kamenets, Marina Viktorovna Pereverzeva, Marina Gennadievna Kruglova Department of Sociology and Philosophy of Art, Russian State Social University, Wilhelm Pieck Street, 4/1, Moscow 129226, Russia Abstract Edited by: Ksenija Bogoeva-Kostovska AIM: The purpose of the work is to study the specifics and evaluate the effectiveness of the use of art-therapeutic Citation: Anufrieva NI, Kamenets AV, Pereverzeva MV, Kruglova MG. Features of the application of art- and gaming technologies based on musical folklore in the course of rehabilitation of children with health limitations. therapeutic and gaming technology based on folk music in rehabilitation and socialization of children with health MATERIALS AND METHODS: The socialization of such children depends largely on the characteristics of health, limitations. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2020 Aug 15; the principles of their training, and the effectiveness of the chosen methods. This justifies the need to analyze the 8(E):373-381. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2020.3588 *Correspondence: Natalia Ivanovna Anufrieva. practical experience and evaluate the results of efforts of specialists who deal with special children. Department of Sociology and Philosophy of Art, Russian State Social University, Wilhelm Pieck Street, 4/1, Moscow RESULTS: The results of the conducted psychological and pedagogical experiment on the use of art-therapeutic and 129226, Russia. -

Psichologijos Žodynas Dictionary of Psychology

ANGLŲ–LIETUVIŲ KALBŲ PSICHOLOGIJOS ŽODYNAS ENGLISH–LITHUANIAN DICTIONARY OF PSYCHOLOGY VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETAS Albinas Bagdonas Eglė Rimkutė ANGLŲ–LIETUVIŲ KALBŲ PSICHOLOGIJOS ŽODYNAS Apie 17 000 žodžių ENGLISH–LITHUANIAN DICTIONARY OF PSYCHOLOGY About 17 000 words VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETO LEIDYKLA VILNIUS 2013 UDK 159.9(038) Ba-119 Apsvarstė ir rekomendavo išleisti Vilniaus universiteto Filosofijos fakulteto taryba (2013 m. kovo 6 d.; protokolas Nr. 2) RECENZENTAI: prof. Audronė LINIAUSKAITĖ Klaipėdos universitetas doc. Dalia NASVYTIENĖ Lietuvos edukologijos universitetas TERMINOLOGIJOS KONSULTANTĖ dr. Palmira ZEMLEVIČIŪTĖ REDAKCINĖ KOMISIJA: Albinas BAGDONAS Vida JAKUTIENĖ Birutė POCIŪTĖ Gintautas VALICKAS Žodynas parengtas įgyvendinant Europos socialinio fondo remiamą projektą „Pripažįstamos kvalifikacijos neturinčių psichologų tikslinis perkvalifikavimas pagal Vilniaus universiteto bakalauro ir magistro studijų programas – VUPSIS“ (2011 m. rugsėjo 29 d. sutartis Nr. VP1-2.3.- ŠMM-04-V-02-001/Pars-13700-2068). Pirminis žodyno variantas (1999–2010 m.) rengtas Vilniaus universiteto Specialiosios psichologijos laboratorijos lėšomis. ISBN 978-609-459-226-3 © Albinas Bagdonas, 2013 © Eglė Rimkutė, 2013 © VU Specialiosios psichologijos laboratorija, 2013 © Vilniaus universitetas, 2013 PRATARMĖ Sparčiai plėtojantis globalizacijos proce- atvejus, kai jų vertimas į lietuvių kalbą gali sams, informacinėms technologijoms, ne- kelti sunkumų), tik tam tikroms socialinėms išvengiamai didėja ir anglų kalbos, kaip ir etninėms grupėms būdingų žodžių, slengo, -

List of Phobias: Beaten by a Rod Or Instrument of Punishment, Or of # Being Severely Criticized — Rhabdophobia

Beards — Pogonophobia. List of Phobias: Beaten by a rod or instrument of punishment, or of # being severely criticized — Rhabdophobia. Beautiful women — Caligynephobia. 13, number — Triskadekaphobia. Beds or going to bed — Clinophobia. 8, number — Octophobia. Bees — Apiphobia or Melissophobia. Bicycles — Cyclophobia. A Birds — Ornithophobia. Abuse, sexual — Contreltophobia. Black — Melanophobia. Accidents — Dystychiphobia. Blindness in a visual field — Scotomaphobia. Air — Anemophobia. Blood — Hemophobia, Hemaphobia or Air swallowing — Aerophobia. Hematophobia. Airborne noxious substances — Aerophobia. Blushing or the color red — Erythrophobia, Airsickness — Aeronausiphobia. Erytophobia or Ereuthophobia. Alcohol — Methyphobia or Potophobia. Body odors — Osmophobia or Osphresiophobia. Alone, being — Autophobia or Monophobia. Body, things to the left side of the body — Alone, being or solitude — Isolophobia. Levophobia. Amnesia — Amnesiphobia. Body, things to the right side of the body — Anger — Angrophobia or Cholerophobia. Dextrophobia. Angina — Anginophobia. Bogeyman or bogies — Bogyphobia. Animals — Zoophobia. Bolsheviks — Bolshephobia. Animals, skins of or fur — Doraphobia. Books — Bibliophobia. Animals, wild — Agrizoophobia. Bound or tied up — Merinthophobia. Ants — Myrmecophobia. Bowel movements, painful — Defecaloesiophobia. Anything new — Neophobia. Brain disease — Meningitophobia. Asymmetrical things — Asymmetriphobia Bridges or of crossing them — Gephyrophobia. Atomic Explosions — Atomosophobia. Buildings, being close to high -

AVAILABLE from ABSTRACT DOCUMENT RESUME Mental

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 431 981 CG 029 333 TITLE Mental Health in Schools: New Roles for School Nurses. Addressing Barriers to Student Learning. INSTITUTION California Univ., Los Angeles. Center for Mental Health in Schools. SPONS AGENCY Health Resources and Services Administration (DHHS/PHS), Washington, DC. Maternal and Child Health Bureau. PUB DATE 1997-04-00 NOTE 298p. AVAILABLE FROM School Mental Health Project, Center for Mental Health in Schools, Dept. of Psychology, UCLA, 405 Hilgard Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90095-1563; Tel: 310-825-3634; Fax: 310-206-8716; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://smhp.psych.ucla.edu (minimal fee to cover copying, postage and handling). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Confidentiality; Due Process; Elementary Secondary Education; *Mental Health; Prevention; *Professional Development; *School Nurses; *Staff Role; Student Development IDENTIFIERS Consent; Screening Programs ABSTRACT This set of three continuing education units is designed to be used as a professional development tool for school nurses. Each unit consists of several sections designed to stand alone. Thus, the total set can be used and taught in a straightforward sequence, or one or more units and sections can be combined into a personalized course. Each section begins with specific objectives and focusing questions to guide reading and review. Interspersed throughout each section is boxed information designed to help the learner think in greater depth about the material. Test questions are provided at the end of each section as an additional study aid. Unit 1, "Placing Mental Health into the Context of Schools and the 21st Century," provides an overview and discusses enhancing health development; addressing barriers to learning; moving toward a comprehensive approach; and responding to students' problems. -

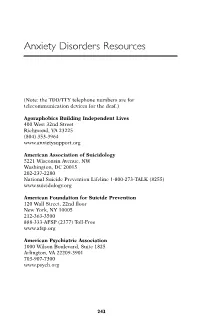

Anxiety Disorders Resources

Anxiety Disorders Resources (Note: the TDD/TTY telephone numbers are for telecommunication devices for the deaf.) Agoraphobics Building Independent Lives 400 West 32nd Street Richmond, VA 23225 (804) 353-3964 www.anxietysupport.org American Association of Suicidology 5221 Wisconsin Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20015 202-237-2280 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-TALK (8255) www.suicidology.org American Foundation for Suicide Prevention 120 Wall Street, 22nd floor New York, NY 10005 212-363-3500 888-333-AFSP (2377) Toll-Free www.afsp.org American Psychiatric Association 1000 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 1825 Arlington, VA 22209-3901 703-907-7300 www.psych.org 243 244 ANXIETY DISORDERS RESOURCES American Psychological Association 750 First Street, N.E. Washington, DC 20002-4242 800-374-2721 202-336-5500 TDD/TTY: 202-336-6213 www.apa.org Anxiety Disorders Association of America 8730 Georgia Avenue, Suite 600 Silver Spring, MD 20910 240-485-1001 www.adaa.org Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies 305 Seventh Avenue, 16th floor New York, NY 10001 (212) 647-1890 www.aabt.org Doctors Guide www.docguide.com Freedom from Fear 308 Seaview Avenue Staten Island, NY 10305 718-351-1717 www.freedomfromfear.org International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 60 Revere Drive, Suite 500 Northbrook IL 60062 847-480-9028 www.istss.org MedlinePlus: Health Information www.medlineplus.gov Mental Health America (formerly National Mental Health Association) 2000 N. Beauregard St., 6t floor Alexandria, VA 22311 800-969-6MHA (6642) 703-684-7722 TTY: 800-433-5959 www.mentalhealthamerica.net ANXIETY DISORDERS RESOURCES 245 National Alliance for the Mentally Ill Colonial Place Three 2107 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22201-3042 800-950-NAMI (6264) 703-524-7600 TDD: 703-516-7227 www.nami.org National Anxiety Foundation 3135 Custer Drive Lexington, KY 40517-4001 606-272-7166 National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder U.S. -

Delusion of Parasitosis: Case Report and Current Concept of Management

Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2011;19(2):110-116 CASE REPORT Delusion of Parasitosis: Case Report and Current Concept of Management Mirna Šitum1, Iva Dediol1, Marija Buljan1, Maja Vurnek Živković1, Danijel Buljan2 1Department of Dermatology and Venereology; 2Department of Psychiatry, Sestre milosrdnice University Hospital Center, Zagreb, Croatia Corresponding author: SUmmARY Delusions of parasitosis (DP) is a primary psychiatric dis- Professor Mirna Šitum, MD, PhD order, a type of monosymptomatic hypochondriac psychosis in which patients believe that ‘bugs’ or ‘parasites’ have infested their skin or that Department of Dermatology and Venereology they have even spread into their visceral organs. Patients with DP usu- Sestre milosrdnice University Hospital Center ally approach different medical specialists, mostly dermatologists and Vinogradska c. 29 primary care physicians because of symptoms presenting as crawling under their skin. Therefore, the exact prevalence of DP is unknown. It HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia is believed that it is a rare disorder but different studies indicate that [email protected] the prevalence is greater than presented. The etiology of this disorder is still unclear. Patients with DP come to a physician with a stereotypic history. Usually the patient has previously addressed many other dif- Received: September 2, 2010 ferent specialists and symptoms are usually present for several months Accepted: April 1, 2011 to years. The main cutaneous symptom is crawling, biting and pruritus due to ‘burrowing of parasites, insects or bugs’ under the skin. Patients with DP are rare but can be very challenging for making the correct diagnosis and for the treatment as well. It is essential to distinguish primary from secondary disorder since the approach to these patients is different. -

Past Life Regression

Past Life Regression Past life regression is a technique that uses hypnosis to recover the memories of past lives or incarnations. Past-life regression is typically undertaken either in pursuit of a spiritual experience, or in a psychotherapeutic setting. Most advocates loosely adhere to beliefs about reincarnation, though religious traditions that incorporate reincarnation generally do not include the idea of repressed memories of past lives. The technique used during past-life regression involves the subject answering a series of questions while hypnotized to reveal identity and events of their past lives. The use of hypnosis and suggestive questions can tend to help the subject to recall his past memories. The source of the memories is more likely that of combine experiences, knowledge, imagination and suggestion or guidance from the hypnotist or regression therapist. Once created, those memories are indistinguishable from memories based on events that occurred during the subject's life. Experiments with subjects undergoing past-life regression indicate that a belief in reincarnation and suggestions by the hypnotist are the two most important factors regarding the contents of memories reported. In the 2nd century BC, Sage Patanjali, in his Yoga Sutras, discussed the idea of the soul becoming burdened with an accumulation of impressions as part of the karma from previous lives. Patanjali called the process of past-life regression “prati- prasav”or "reverse birthing" and saw it as addressing current problems through memories of past lives. Past life regression can be found in Jainism. The seven truths of Jainism deal with the soul and its attachment to karma and Moksha. -

Cultural Geographies

Cultural Geographies http://cgj.sagepub.com/ Ecological anxiety disorder: diagnosing the politics of the Anthropocene Paul Robbins and Sarah A. Moore Cultural Geographies 2013 20: 3 DOI: 10.1177/1474474012469887 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cgj.sagepub.com/content/20/1/3 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Cultural Geographies can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cgj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cgj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Jan 7, 2013 What is This? Downloaded from cgj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN on January 14, 2013 CGJ20110.1177/1474474012469887Cultural geographiesRobbins and Moore 4698872012 Article cultural geographies 20(1) 3 –19 Ecological anxiety disorder: © The Author(s) 2012 Reprints and permission: sagepub. co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav diagnosing the politics of the DOI: 10.1177/1474474012469887 Anthropocene cgj.sagepub.com Paul Robbins University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA Sarah A. Moore University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA Abstract The quickly changing character of the global environment has predicated a number of crises in the sciences of biology and ecology. Specifically, the rapid rate of ecological change has led to the proliferation of novel ecologies. These unprecedented ecosystems and assemblages challenge the scientific, as well as cultural, core of many disciplines. This has led to divisive debates over what constitutes a ‘natural’ system state, and over what kinds of interventions, if any, should be advocated by scientists. In this paper, we review the nature of the recent discomfort, conflict, and ambivalence experienced in some sciences. -

List of Phobias and Simple Cures.Pdf

Phobia This article is about the clinical psychology. For other uses, see Phobia (disambiguation). A phobia (from the Greek: φόβος, Phóbos, meaning "fear" or "morbid fear") is, when used in the context of clinical psychology, a type of anxiety disorder, usually defined as a persistent fear of an object or situation in which the sufferer commits to great lengths in avoiding, typically disproportional to the actual danger posed, often being recognized as irrational. In the event the phobia cannot be avoided entirely the sufferer will endure the situation or object with marked distress and significant interference in social or occupational activities.[1] The terms distress and impairment as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR) should also take into account the context of the sufferer's environment if attempting a diagnosis. The DSM-IV-TR states that if a phobic stimulus, whether it be an object or a social situation, is absent entirely in an environment - a diagnosis cannot be made. An example of this situation would be an individual who has a fear of mice (Suriphobia) but lives in an area devoid of mice. Even though the concept of mice causes marked distress and impairment within the individual, because the individual does not encounter mice in the environment no actual distress or impairment is ever experienced. Proximity and the degree to which escape from the phobic stimulus should also be considered. As the sufferer approaches a phobic stimulus, anxiety levels increase (e.g. as one gets closer to a snake, fear increases in ophidiophobia), and the degree to which escape of the phobic stimulus is limited and has the effect of varying the intensity of fear in instances such as riding an elevator (e.g.