1The Question of Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

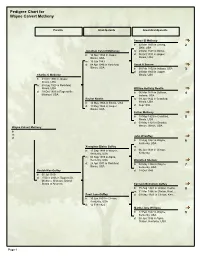

Pedigree Chart for Wayne Calvert Metheny

Pedigree Chart for Wayne Calvert Metheny Parents Grandparents Great-Grandparents Samuel B Matheny b: 22 Mar 1830 in Licking, 2 Ohio, USA Jonathan Calvert Metheney m: 29 Mar 1849 in Illinois b: 14 Nov 1860 in Jasper, d: 06 Oct 1891 in Jasper, Illinois, USA Illinois, USA m: 19 Jun 1883 d: 04 Apr 1943 in Rockford, Sarah A Sovern Illinois, USA b: 08 Feb 1832 in Indiana, USA 3 d: 29 Mar 1900 in Jasper, Charles C Metheny Illinois, USA b: 24 Oct 1906 in Jasper, Illinois, USA m: 08 Aug 1929 in Rockford, Illinois, USA William Holliday Newlin d: 19 Oct 1993 in Rogersville, b: 06 Mar 1818 in Sullivan, 4 Missouri, USA Indiana, USA Rachel Newlin m: 09 Jun 1842 in Crawford, b: 12 May 1866 in Illinois, USA Illinois, USA d: 11 May 1924 in Jasper, d: Sep 1892 Illinois, USA Esther Metheny b: 18 May 1823 in Crawford, 5 Illinois, USA d: 09 May 1928 in Decatur, Macon, Illinois, USA Wayne Calvert Metheny b: m: John W Guffey d: b: 18 Aug 1862 in Wayne, 6 Kentucky, USA Xenophon Blaine Guffey m: b: 17 Sep 1888 in Wayne, d: 06 Jun 1931 in Clinton, Kentucky, USA Kentucky m: 08 Sep 1909 in Alpha, Kentucky, USA Winnifred Shelton d: 24 Apr 1971 in Rockford, b: 02 May 1866 in Wayne, 7 Illinois, USA Kentucky, USA Beulah Mae Guffey d: 18 Oct 1946 b: 05 Jul 1910 d: 15 Dec 2006 in Rogersville, Webster, Missouri, United States of America Ephraim McCullom Guffey b: 15 Aug 1841 in Clinton, Kentu… 8 m: 31 Mar 1866 in Clinton, Kent… Pearl Jane Guffey d: 03 May 1923 in Clinton, Kent… b: 13 Jun 1891 in Clinton, Kentucky, USA d: 12 Feb 1923 Martha Jane Williams b: 12 Feb 1842 -

EDUCATION in LANCASHIRE and CHESHIRE, 1640-1660 Read 18

EDUCATION IN LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE, 1640-1660 BY C. D. ROGERS, M.A., M.ED. Read 18 November 1971 HE extraordinary decades of the Civil War and Interregnum, Twhen many political, religious, and economic assumptions were questioned, have been seen until recently as probably the greatest period of educational innovation in English history. Most modern writers have accepted the traditional picture of puritan attitudes and ideas, disseminated in numerous published works, nurtured by a sympathetic government, developing into an embryonic state system of education, a picture given added colour with details of governmental and private grants to schools.1 In 1967, however, J. E. Stephens, in an article in the British Journal of Educational Studies, suggested that detailed investigations into the county of York for the period 1640 to 1660 produced a far less admirable view of the general health of educational institutions, and concluded that 'if the success of the state's policy towards education is measured in terms of extension and reform, it must be found wanting'.2 The purpose of this present paper is twofold: to examine the same source material used by Stephens, to see whether a similar picture emerges for Lancashire and Cheshire; and to consider additional evidence to modify or support his main conclusions. On one matter there is unanimity. The release of the puritan press in the 1640s made possible a flood of books and pamphlets not about education in vacuo, but about society in general, and the role of the teacher within it. The authors of the idealistic Nova Solyma and Oceana did not regard education as a separate entity, but as a fundamental part of their Utopian structures. -

The Politics of Gossip in Early Virginia

"SEVERAL UNHANDSOME WORDS": THE POLITICS OF GOSSIP IN EARLY VIRGINIA Christine Eisel A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2012 Committee: Ruth Wallis Herndon, Advisor Timothy Messer-Kruse Graduate Faculty Representative Stephen Ortiz Terri Snyder Tiffany Trimmer © 2012 Christine Eisel All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ruth Wallis Herndon, Advisor This dissertation demonstrates how women’s gossip in influenced colonial Virginia’s legal and political culture. The scandalous stories reported in women’s gossip form the foundation of this study that examines who gossiped, the content of their gossip, and how their gossip helped shape the colonial legal system. Focusing on the individuals involved and recreating their lives as completely as possible has enabled me to compare distinct county cultures. Reactionary in nature, Virginia lawmakers were influenced by both English cultural values and actual events within their immediate communities. The local county courts responded to women’s gossip in discretionary ways. The more intimate relations and immediate concerns within local communities could trump colonial-level interests. This examination of Accomack and York county court records from the 1630s through 1680, supported through an analysis of various colonial records, family histories, and popular culture, shows that gender and law intersected in the following ways. 1. Status was a central organizing force in the lives of early Virginians. Englishmen punished women who gossiped according to the status of their husbands and to the status of the objects of their gossip. 2. English women used their gossip as a substitute for a formal political voice. -

The Short History of Science

PHYSICS FOUNDATIONS SOCIETY THE FINNISH SOCIETY FOR NATURAL PHILOSOPHY PHYSICS FOUNDATIONS SOCIETY THE FINNISH SOCIETY FOR www.physicsfoundations.org NATURAL PHILOSOPHY www.lfs.fi Dr. Suntola’s “The Short History of Science” shows fascinating competence in its constructively critical in-depth exploration of the long path that the pioneers of metaphysics and empirical science have followed in building up our present understanding of physical reality. The book is made unique by the author’s perspective. He reflects the historical path to his Dynamic Universe theory that opens an unparalleled perspective to a deeper understanding of the harmony in nature – to click the pieces of the puzzle into their places. The book opens a unique possibility for the reader to make his own evaluation of the postulates behind our present understanding of reality. – Tarja Kallio-Tamminen, PhD, theoretical philosophy, MSc, high energy physics The book gives an exceptionally interesting perspective on the history of science and the development paths that have led to our scientific picture of physical reality. As a philosophical question, the reader may conclude how much the development has been directed by coincidences, and whether the picture of reality would have been different if another path had been chosen. – Heikki Sipilä, PhD, nuclear physics Would other routes have been chosen, if all modern experiments had been available to the early scientists? This is an excellent book for a guided scientific tour challenging the reader to an in-depth consideration of the choices made. – Ari Lehto, PhD, physics Tuomo Suntola, PhD in Electron Physics at Helsinki University of Technology (1971). -

Seiichiro Ito (Ohtsuki City College, Japan)

Neighbour country, Holland: an ideal model to follow, or just an enemy? Seiichiro Ito (Ohtsuki City College, Japan) Abstract In the seventeenth century, particularly in its first half, the English pamphleteers often argued that the English should learn the manner of herring fishing from the Dutch and it is essential for the success of the English trade. While they tended to focus on the technical aspects of fishing business, around mid-century some pamphleteers showed their interest in the Dutch society as a whole. They shared the list of their merits to learn from the Dutch model, such as the management of trade, low customs, low interest rates, and banking. Over the Navigation Act of 1651, some were supportive and some were against, but both sides shared the same images of Holland. From around 1670 the styles of the discourses of the pamphleteers who discuss trade also changed. They got more analytical and systematic. Roger Coke was an example. Introduction In 1651 where England was stepping into the way to the war with the Dutch, Thomas Hobbes was also one of those who had a complex feeling against them. Hobbes expresses it as follows: ‘I doubt not, but many men, have been contented to see the late troubles in England, out of an imitation of the Low Countries; supposing there needed no more to grow rich, than to change, as they had done, the forme of their Government.’ (Hobbes, Leviathan, 1991, p. 225.) Hobbes here shows one of reasons why the Common-wealth would lead to its dissolution. The example of the government of a neighbour country ‘disposeth men to alteration of the forme already setled’, just as false doctrines do. -

And Charles II

Gellera: James Dundas (c.1620−1679) and Charles II Title Page James Dundas (c.1620−1679) and Charles II: Religious Tolerance, Freedom of Conscience, and the Limits of the Sovereign Giovanni Gellera ORCID IDENTIFIER 0000-0002-8403-3170 Section de philosophie, Université de Lausanne [email protected] The Version of Scholarly Record of this article (in French) is published in: “James Dundas (c. 1620-1679) et Charles II. Tolérance religieuse, liberté de conscience et limites de la souveraineté”, dans Yves Krumenacker, Noémie Recous (dir.), Le Protestant et l'Hétérodoxe. Entre Eglises et Etats (XVIe- XVIIIe siècles), Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2019, pp. 39−58. 1 Gellera: James Dundas (c.1620−1679) and Charles II JAMES DUNDAS (C.1620−1679) AND CHARLES II: RELIGIOUS TOLERANCE, FREEDOM OF CONSCIENCE, AND THE LIMITS OF THE SOVEREIGN1 INTRODUCTION “Mitchel knew that [his prison wardens] thought him embittered, even deranged. But he saw through their weakness: he had only carried the principles that they all upheld − the right of God’s people to resist unholy rule, the duty of God’s Scotland to defend the Covenant against prelatic blasphemy − to their logical conclusion. What they shied away from was their own fear: they were afraid to strike the righteous blow, to be the sword of the Lord and of Gideon.”2 These words refer to the fictional character James Mitchel in the historical novel The Fanatic by the contemporary Scottish author James Robertson. The novel narrates the incarceration of the “justified sinner” Mitchel after he attempted to assassinate one of the great enemies of the Covenanters, archbishop James Sharp, in 1668. -

I. Living Our Faith 1. a Brief History

I. Living Our Faith 1. A Brief History Quakerism emerged in 17th century England, a period of religious and political upheaval in which the inherent authority of royalty, feudal lords, and the church were all actively questioned. The years had ended in which those who would translate the Bible into English were persecuted. The King James Bible of 1611 made the Scriptures available to more English-speaking people than ever before. Now people could read the Word of God for themselves, one by oneindividually or together, in their native tongue. Many beliefs that became part of Quaker faith and practice were not original with Quakers, who felt and knew the powerful currents of change in their time. A sect called the Levellers stressed human equality. The Puritans sought simpler forms of worship and believed that individuals, reading the Bible, could hear and understand the voice of God. The Seekers, disillusionedDisillusioned with churches altogether, waited for God to be revealed,the Seekers waited, sometimes in silence, for God to be revealed. The Ranters knew that God was indwelling in each soul, though their ways of expressing what they thought was the Spirit included overindulgence in tobacco and alcohol. The phrase “the Inner Light” was not original with Quakers; nor was the belief that there was something of God in each person. Yet Quakers survived when other sects did not, absorbing some members from those other groups. Why? Many answers have been suggested, and there is truth in each one: Quakers had gifted leaders who were committed to ministry and supported each other as “Publishers of Truth.” Committed Quakers, unlike many in other sects, did not recant when called before the authorities. -

History As Points and Lines

HISTORY AS POINTS AND LINES by Yuri Tarnopolsky and Ulf Grenander Manuscript 1998-2003 Yuri Tarnopolsky and Ulf Grenander, 2006 1 2 Foreword (2006) Most of this manuscript was finished by 1998. In 2001 the world entered a turbulent transition state toward an unknown future. In 2003 we added Chapter 28, A sunny day in September . Facing global uncertainty from many directions—climate change, energy constraints, new forms of warfare, borderless world, incompetence of governments—we need to look for a scientific consensus on complexity, as opposed to the divisive political, moral, and religious approaches. Testing the ideas of this book against the dramatic beginning of the twenty-first century, we feel confident that the pattern view of the world can be an effective way to understand the developing systems of unprecedented complexity. The intent of this manuscript is to attract attention to Pattern Theory as the science of complex systems. Complexity as subject presumes a complex audience. The style reflects our desire to educate, stimulate, and entertain, while introducing the reader to new and little known or forgotten ideas. The manuscript does not reflect the recent developments in non-numerical Pattern Theory, among which Patterns of Thought by Ulf Grenander should be mentioned in the first place. Patterns and Repertoire in History by Bertrand M. Roehner and Tony Syme ( Harvard University Press, 2002) was an important step toward the legitimization of the search for new ways in scientific study of history. Jared Diamond's Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (Viking, 2004) approaches the subject from a different angle but remarkably close to the spirit of Pattern Theory. -

Descendants of Hugh 3Rd Earl of Norfolk Macanluain Bigod MCS

Descendants of Hugh 3rd Earl of Norfolk MacAnluain Bigod MCS Generation 1 1. HUGH 3RD EARL OF NORFOLK MACANLUAIN BIGOD1 MCS was born about 1186 in Thetford, Norfolk, England. He died on 18 Feb 1225 in England. He married Maud OR Mahelt OR Matilda Countess Marshal of England, daughter of William 1st Earl of Pembroke Marshall and Isabel 4th Countess of Pembroke Fitzgilbert De Clare, before 1207 in Pembroke, Pembrokeshire, Wales. She was born in 1194 in Pembroke, Pembrokeshire, Wales. She died on 27 Mar 1248 in Tintern Abbey, Chapel Hill, Monmouthshire, England. Hugh 3rd Earl of Norfolk MacAnluain Bigod MCS and Maud OR Mahelt OR Matilda Countess Marshal of England had the following children: 2. i. ISABEL2 BIGOD was born about 1210 in Norfolk, Norfolk, England. She died in 1239 in Weobley, Herefordshire, England. She married (1) GILBERT DE LACY, son of Walter De Lacy and Margaret De Braose, about 1225 in Norfolk, Norfolk, England. He was born about 1206 in Dublin, Ireland. He died in 1234. She married (2) JOHN FITZGEOFFREY, son of Geoffrey Fitzpiers and Eveline DeClare, in 1230 in Shere, Surrey, England. He was born in 1215 in Shere, Surrey, England. He died on 23 Nov 1258 in Essex, England. ii. ROGER 4TH EARL OF NORFOLK BIGOD MCS was born in 1212 in Thetford, Norfolk, England. He died in Mar 1270 in Thetford, Norfolk, England. He married Isabella Princess of Scotland, daughter of William I 'The Lion' Earl of Huntingdon King of Scotland and Ermengarde De Beaumont Queen of Scotland, in 1225 in Alnwick, Northumberland, England. -

(Dr.) Anjum Ashrafi HOD Department of History BS College, Danapur

Prof. (Dr.) Anjum Ashrafi HOD Department of History B. S. College, Danapur, Patna B.A. Part I RESTORATION 0F 1660 IN ENGLAND The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars, came to be known as the Interregnum (1649–1660). The term Restoration is also used to describe the period of several years after, in which a new political settlement was established. It is very often used to cover the whole reign of Charles II (1660–1685) and often the brief reign of his younger brother James II (1685–1688). In certain contexts it may be used to cover the whole period of the later Stuart monarchs as far as the death of Queen Anne and the accession of the Hanoverian George I in 1714. For example, Restoration comedy typically encompasses works written as late as 1710. After the Lord Protector from 1658-9 Richard Cromwell ceded power to the Rump Parliament, Charles Fleetwood and John Lambert (general) John Lambert then dominated government for a year. On 20 October 1659 George Monck, the governor of Scotland under the Cromwells, marched south with his army from Scotland to oppose Fleetwood and Lambert. Lambert's army began to desert him, and he returned to London almost alone whilst Monck marched to London unopposed. The Presbyterian members, excluded in Pride's Purge of 1648, were recalled, and on 24 December the army restored the Long Parliament. -

Humanism and Protestantism in Early Modern English Education

Humanism and Protestantism in Early Modern English Education Humanism and Protestantism in Early Modern English Education IAN GREEN University of Edinburgh, UK © Ian Green 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Ian Green has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington Surrey, GU9 7PT VT 05401–4405 England USA www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Green, Ian M. Humanism and Protestantism in early modern English education. – (St Andrews studies in Reformation history) 1. Education – England – History – 16th century 2. Education – England – History – 17th century 3. Humanism – England – History – 16th century 4. Humanism – England – History – 17th century 5. Protestantism – England – History – 16th century 6. Protestantism – England – History – 17th century 7. Reformation – England I. Title 370.9’42’0903 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Green, Ian M. Humanism and Protestantism in early modern English education / Ian M. Green. p. cm. – (St Andrews studies in Reformation history) Includes index. ISBN 978–0–7546–6368–3 (alk. paper) – ISBN 978–0–7546–9468–7 (ebook) 1. Education -

Roots of Social Enterprise : Entrepreneurial Philanthropy, England 1600-1908

This is a repository copy of Roots of Social Enterprise : Entrepreneurial Philanthropy, England 1600-1908. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/125978/ Version: Accepted Version Article: MacDonald, Matthew and Howorth, Carole orcid.org/0000-0002-5547-687X (2018) Roots of Social Enterprise : Entrepreneurial Philanthropy, England 1600-1908. Social Enterprise Journal. pp. 4-21. ISSN 1750-8614 https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-03-2017-0020 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Social Enterprise Journal Roots of Social Enterprise: Entrepreneurial Philanthropy, Social EnterpriseEngland 1600-1908 Journal Journal: Social Enterprise Journal Manuscript ID SEJ-03-2017-0020.R1 Manuscript Type: Research aper social enterprise, history, review, welfare provision, poverty relief, Keywords: entrepreneurship http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/sejnl Page 1 of 34 Social Enterprise Journal 1 2 3 Roots of Social Enterprise: Entrepreneurial Philanthropy, England 1600-1908 4 5 6 A stract 7 8 Purpose: Insights into the roots of social enterprise from before the term was adopted are 9 10 provided by examining histories of charitable service and comparing current 11 12 understandings of social enterprise.