Isaac Barrow: Builder of Foundations for a Modern Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Value of Books

The Value of Books: The York Minster Library as a social arena for commodity exchange. Master’s thesis, 60 credits, Spring 2018 Author: Luke Kelly Supervisor: Gudrun Andersson Seminar chair: Dag Lindström Date: 12/01/2018 HISTORISKA INSTITUTIONEN It would be the height of ignorance, and a great irony, if within a work focused on the donations of books, that the author fails to acknowledge and thank those who assisted in its production. Having been distant from both Uppsala and close friends whilst writing this thesis, (and missing dearly the chances to talk to others in person), it goes without saying that this work would not be possible if I had not had the support of many generous and wonderful people. Although to attempt to thank all those who assisted would, I am sure, fail to acknowledge everyone, a few names should be highlighted: Firstly, thank you to all of my fellow EMS students – the time spent in conversation over coffees shaped more of this thesis than you would ever realise. Secondly, to Steven Newman and all in the York Minster Library – without your direction and encouragement I would have failed to start, let alone finish, this thesis. Thirdly, to all members of History Node, especially Mikael Alm – the continued enthusiasm felt from you all reaches further than you know. Fourthly, to my family and closest – thank you for supporting (and proof reading, Maja Drakenberg) me throughout this process. Any success of the work can be attributed to your assistance. Finally, to Gudrun Andersson – thank you for offering guidance and support throughout this thesis’ production. -

Social and Cultural Functions of the Local Press in Preston, Lancashire, 1855-1900

Reading the local paper: Social and cultural functions of the local press in Preston, Lancashire, 1855-1900 by Andrew Hobbs A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire November 2010 ABSTRACT This thesis demonstrates that the most popular periodical genre of the second half of the nineteenth century was the provincial newspaper. Using evidence from news rooms, libraries, the trade press and oral history, it argues that the majority of readers (particularly working-class readers) preferred the local press, because of its faster delivery of news, and because of its local and localised content. Building on the work of Law and Potter, the thesis treats the provincial press as a national network and a national system, a structure which enabled it to offer a more effective news distribution service than metropolitan papers. Taking the town of Preston, Lancashire, as a case study, this thesis provides some background to the most popular local publications of the period, and uses the diaries of Preston journalist Anthony Hewitson as a case study of the career of a local reporter, editor and proprietor. Three examples of how the local press consciously promoted local identity are discussed: Hewitson’s remoulding of the Preston Chronicle, the same paper’s changing treatment of Lancashire dialect, and coverage of professional football. These case studies demonstrate some of the local press content that could not practically be provided by metropolitan publications. The ‘reading world’ of this provincial town is reconstructed, to reveal the historical circumstances in which newspapers and the local paper in particular were read. -

Hub Letter Info Jan 21

Dear Parents, Wednesday 6th January 2021 Re: Closure of Schools due to Coronavirus We would like to thank you all for your patience at this difficult time. As I am sure you heard yesterday the Chief Minister ordered the closure of most schools for most pupils on the Isle of Man from the end of school today. We know that parents/carers will seek to keep their children safe by keeping them at home and will follow the Government’s advice. We very much appreciate your support in this and know that, if we all work together, we have the best chance of reducing the spread of Covid-19. The Government has asked parents to keep their children at home wherever possible, and asked schools to remain open only for those children who are designated as ‘vulnerable’ or are the children of ‘key workers’. It is important to understand that: • If it is possible for children to stay at home then they should. • Parents/carers should also do all they can to ensure children are not mixing socially in a way that could spread the virus. They should observe the same social distancing principles as adults. • Many parents who are key workers may be able to ensure their child is kept at home. Every child who can be safely at home should be. • The fewer children making the journey to school and the fewer children in educational settings the lower the risk that the virus can spread and infect vulnerable individuals in wider society. • Parents can choose to keep children away from school without any concern of repercussion. -

Chetham Miscellanies

942.7201 M. L. C42r V.19 1390748 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 00728 8746 REMAINS HISTORICAL k LITERARY NOTICE. The Council of the Chetham Society have deemed it advisable to issue as a separate Volume this portion of Bishop Gastrell's Notitia Cestriensis. The Editor's notice of the Bishop will be added in the concluding part of the work, now in the Press. M.DCCC.XLIX. REMAINS HISTORICAL & LITERARY CONNECTED WITH THE PALATINE COUNTIES OF LANCASTER AND CHESTER PUBLISHED BY THE CHETHAM SOCIETY. VOL. XIX. PRINTED FOR THE CHETHAM SOCIETY. M.DCCC.XLIX. JAMES CROSSLEY, Esq., President. REV. RICHARD PARKINSON, B.D., F.S.A., Canon of Manchester and Principal of St. Bees College, Vice-President. WILLIAM BEAMONT. THE VERY REV. GEORGE HULL BOWERS, D.D., Dean of Manchester. REV. THOMAS CORSER, M.A. JAMES DEARDEN, F.S.A. EDWARD HAWKINS, F.R.S., F.S.A., F.L.S. THOMAS HEYWOOD, F.S.A. W. A. HULTON. REV. J. PICCOPE, M.A. REV. F. R. RAINES, M.A., F.S.A. THE VEN. JOHN RUSHTON, D.D., Archdeacon of Manchester. WILLIAM LANGTON, Treasurer. WILLIAM FLEMING, M.D., Hon. SECRETARY. ^ ^otttia €mtvitmis, HISTORICAL NOTICES OF THE DIOCESE OF CHESTER, RIGHT REV. FRANCIS GASTRELL, D.D. LORD BISHOP OF CHESTER. NOW FIRST PEINTEB FROM THE OEIGINAl MANITSCEIPT, WITH ILLrSTBATIVE AND EXPLANATOEY NOTES, THE REV. F. R. RAINES, M.A. F.S.A. BUBAL DEAN OF ROCHDALE, AND INCUMBENT OF MILNEOW. VOL. II. — PART I. ^1 PRINTED FOR THE GHETHAM SOCIETY. M.DCCC.XLIX. 1380748 CONTENTS. VOL. II. — PART I i¥lamf)e£{ter IBeanerp* page. -

Manx Traditional Dance Revival 1929 to 1960

‘…while the others did some capers’: the Manx Traditional Dance revival 1929 to 1960 By kind permission of Manx National Heritage Cinzia Curtis 2006 This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Master of Arts in Manx Studies, Centre for Manx Studies, University of Liverpool. September 2006. The following would not have been possible without the help and support of all of the staff at the Centre for Manx Studies. Special thanks must be extended to the staff at the Manx National Library and Archive for their patience and help with accessing the relevant resources and particularly for permission to use many of the images included in this dissertation. Thanks also go to Claire Corkill, Sue Jaques and David Collister for tolerating my constant verbalised thought processes! ‘…while the others did some capers’: The Manx Traditional Dance Revival 1929 to 1960 Preliminary Information 0.1 List of Abbreviations 0.2 A Note on referencing 0.3 Names of dances 0.4 List of Illustrations Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 Methodology 1 1.2 Dancing on the Isle of Man in the 19th Century 5 Chapter 2: The Collection 2.1 Mona Douglas 11 2.2 Philip Leighton Stowell 15 2.3 The Collection of Manx Dances 17 Chapter 3: The Demonstration 3.1 1929 EFDS Vacation School 26 3.2 Five Manx Folk Dances 29 3.3 Consolidating the Canon 34 Chapter 4: The Development 4.1 Douglas and Stowell 37 4.2 Seven Manx Folk Dances 41 4.3 The Manx Folk Dance Society 42 Chapter 5: The Final Figure 5.1 The Manx Revival of the 1970s 50 5.2 Manx Dance Today 56 5.3 Conclusions -

Letter to Church Members (February 2021)

ST JAMES’ CHURCH RHOSDDU ST JOHN’S CHURCH, RHOSNESNI From the Revd Sarah Errington The Vicarage Priest-in-Charge 160 Borras Road Telephone: 01978 266018 WREXHAM e-mail: [email protected] LL13 9ER 10 February 2021 Hallo Everyone! Ash Wednesday and Lent I hope you are finding the weekly mailings helpful in your spiritual reflections and activities. Last week’s package included a sheet with a suggested service/activity for Ash Wednesday, which is next week, and marks the beginning of Lent and our preparations for Easter. I have considered doing a streamed service for Ash Wednesday, but in the end decided that I don’t have the capacity. The Mission Area leaflet attached gives details of online Ash Wednesday services in the Mission Area; or you might like to watch the service from St Asaph Cathedral at 7.00 pm on Wednesday, on the Cathedral Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/StAsaphCathedral/live/, or the Cathedral website: https://stasaphcathedral.wales/. Next week I will be sending out two resources which you might like to use through the weeks of Lent. The first is called A Journey Through Mark’s Gospel, and provides a number of readings and reflections for each week of Lent. The second is called Baking Through Lent, and focusses on the Sunday gospel reading for each week; it provides a recipe which is linked to the reading, which you might like to bake. If you do that, and you have the opportunity before your food is scoffed (!), it would be fantastic to share some photos of what you’ve baked! You can either post them on our Facebook page/group, or send them to me by email, and I’ll post them for you. -

Nama-2017-88.2

VOL 88, No.2 To preserve “Whatever is left to us of our ancient heritage.” T.E. Brown Summer 2017 ish passport that you will need to get an Electronic Travel Application (ETA) visa in order to travel to Canada. They are available online at http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/visit/eta.asp) COME ONE, COME ALL I have flown to Seattle and then taken the Victoria Clipper, TO THE 2018 NAMA CONVENTION which takes approximately 3 hours. The advantage to this JUNE 21-25, 2018 IN VICTORIA, method is that the landing port is less than a mile/kilometer from the hotel. Very walkable. BRITISH COLUMBIA! There is a car/people ferry from MESSAGE FROM KATY PRENDERGAST Port Angeles, WA, to Victoria, the company is Black Ball Ferry Line. There are ferries approximately We have so many fun things planned for next year’s Conven- 4 times a day. This is also very tion in Canada, the third country of the North American Manx walkable and the port for this is 100 Association. We are thrilled we will be there during its 150th feet in front of the Victoria Clipper. Anniversary! We have some amazing things planned: including whale watching or a Hop-on Hop-off bus tour; Afternoon Tea There is a car/people ferry from Tsawwassen to Vancouver at the Fairmount Empress; a trip to Butchart Gardens; Manx Island, and you are approximately 20mi/32km outside of Break-out sessions and plenty of opportunities to catch up downtown Victoria. with old friends. I have taken a float plane, which has some advantages in that First though – Have you you fly from Seattle to Victoria Inner Harbor in approximate- asked yourself how to ly 45 minutes. -

The Cathedral Church of Saint Asaph; a Description of the Building

SAINT ASAPH THE CATHEDRAL AND SEE WITH PLAN AND ILLUSTRATIONS BELL'S CATHEDRAL SERIES College m of Arskiitecture Liorary Coraell U»iversity fyxmll Utttomitg JilratJg BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hettrg HI. Sage 1S91 A,'i..c.^.'^...vs> Vfe\p^.\.\:gr... 1357 NA 5460.53™"""'™""'"-"'"'^ The cathedral church of Saint Asaph; a de 3 1924 015 382 983 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924015382983 BELL'S CATHEDRAL SERIES SAINT ASAPH 7^^n{M3' 7 ^H THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH OF SAINT ASAPH A DESCRIPTION OF THE BUILD- ING AND A SHORT HISTORY OF THE SEE BY PEARCE B. IRONSIDE BAX WITH XXX ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON GEORGE BELL & SONS 1904 A/A , " S4-fcO CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO. TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON. ' PREFACE The author published a monograph on " St. Asaph Cathedral in 1896, which has formed the basis of the present handbook. The historical documents are few, and the surviving evidence of the past with regard to our smallest cathedral is scanty at the best. The chief books of reference have been Browne Willis's valuable "Survey of St. Asaph,'' published in 1720, also Edwards' edition of the same published at Wrexham in 1801, and the learned work by the Ven. Archdeacon Thomas, M.A., F.S.A., on " The Diocese of St. Asaph." " Storer's Cathedrals," pub- lished in i8ig, together with similar works, have also been consulted. -

A Report on the Developments in Women's Ministry in 2018

A Report on the Developments in Women’s Ministry in 2018 WATCH Women and the Church A Report on the Developments in Women’s Ministry 2018 In 2019 it will be: • 50 years since women were first licensed as Lay Readers • 25 years since women in the Church of England were first ordained priests • 5 years since legislation was passed to enable women to be appointed bishops In 2018 • The Rt Rev Sarah Mullaly was translated from the See of Crediton to become Bishop of London (May 12) and the Very Rev Viv Faull was consecrated on July 3rd, and installed as Bishop of Bristol on Oct 20th. Now 4 diocesan bishops (out of a total of 44) are women. In December 2018 it was announced that Rt Rev Libby Lane has been appointed the (diocesan) Bishop of Derby. • Women were appointed to four more suffragan sees during 2018, so at the end of 2018 12 suffragan sees were filled by women (from a total of 69 sees). • The appointment of two more women to suffragan sees in 2019 has been announced. Ordained ministry is not the only way that anyone, male or female, serves the church. Most of those who offer ministries of many kinds are not counted in any way. However, WATCH considers that it is valuable to get an overview of those who have particular responsibilities in diocese and the national church, and this year we would like to draw attention to The Church Commissioners. This group is rarely noticed publicly, but the skills and decisions of its members are vital to the funding of nearly all that the Church of England is able to do. -

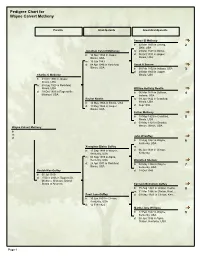

Pedigree Chart for Wayne Calvert Metheny

Pedigree Chart for Wayne Calvert Metheny Parents Grandparents Great-Grandparents Samuel B Matheny b: 22 Mar 1830 in Licking, 2 Ohio, USA Jonathan Calvert Metheney m: 29 Mar 1849 in Illinois b: 14 Nov 1860 in Jasper, d: 06 Oct 1891 in Jasper, Illinois, USA Illinois, USA m: 19 Jun 1883 d: 04 Apr 1943 in Rockford, Sarah A Sovern Illinois, USA b: 08 Feb 1832 in Indiana, USA 3 d: 29 Mar 1900 in Jasper, Charles C Metheny Illinois, USA b: 24 Oct 1906 in Jasper, Illinois, USA m: 08 Aug 1929 in Rockford, Illinois, USA William Holliday Newlin d: 19 Oct 1993 in Rogersville, b: 06 Mar 1818 in Sullivan, 4 Missouri, USA Indiana, USA Rachel Newlin m: 09 Jun 1842 in Crawford, b: 12 May 1866 in Illinois, USA Illinois, USA d: 11 May 1924 in Jasper, d: Sep 1892 Illinois, USA Esther Metheny b: 18 May 1823 in Crawford, 5 Illinois, USA d: 09 May 1928 in Decatur, Macon, Illinois, USA Wayne Calvert Metheny b: m: John W Guffey d: b: 18 Aug 1862 in Wayne, 6 Kentucky, USA Xenophon Blaine Guffey m: b: 17 Sep 1888 in Wayne, d: 06 Jun 1931 in Clinton, Kentucky, USA Kentucky m: 08 Sep 1909 in Alpha, Kentucky, USA Winnifred Shelton d: 24 Apr 1971 in Rockford, b: 02 May 1866 in Wayne, 7 Illinois, USA Kentucky, USA Beulah Mae Guffey d: 18 Oct 1946 b: 05 Jul 1910 d: 15 Dec 2006 in Rogersville, Webster, Missouri, United States of America Ephraim McCullom Guffey b: 15 Aug 1841 in Clinton, Kentu… 8 m: 31 Mar 1866 in Clinton, Kent… Pearl Jane Guffey d: 03 May 1923 in Clinton, Kent… b: 13 Jun 1891 in Clinton, Kentucky, USA d: 12 Feb 1923 Martha Jane Williams b: 12 Feb 1842 -

GENERAL SYNOD GENERAL SYNOD ELECTIONS 2015 Report by the Business Committee

GS 1975 GENERAL SYNOD GENERAL SYNOD ELECTIONS 2015 Report by the Business Committee Summary The Synod is invited to approve the allocation of places for the directly elected diocesan representatives to the Lower Houses of the Convocations and to the House of Laity for the quinquennium 2015-2020. The calculations have been made in accordance with the provisions of Canon H 2 and Rule 36 of the Church Representation Rules. A summary of the proposed allocation for clergy places and any change from the allocation in 2010 is set out at Appendix A and for lay places at Appendix B. Appendix C sets out the overall position. The allocations of eighteen dioceses will be different under the proposed allocation from the allocation in the current quinquennium, eleven in the Province of Canterbury and seven in the Province of York. Background 1. The Business Committee seeks the approval of the General Synod for the customary resolutions to allocate places for directly elected diocesan representatives to the Lower Houses of the Convocations and to the House of Laity for the quinquennium 2015-2020. 2. The legal requirements on which these resolutions are based are contained in Canon H 2 and Rule 36 of the Church Representation Rules. 3. While the principal reason for this report to the Synod is to provide the necessary background information to the resolutions before the Synod, we are also taking the opportunity to remind the Synod of the constitutional provisions affecting the timetable and to give notice of future plans for advising dioceses on the procedures to be followed. -

October 2007 Kiaull Manninagh Jiu

Manx Music Today October 2007 Kiaull Manninagh Jiu Bree 2007 a manx feis for 11 to 16 year olds On Saturday 27th and Sunday 28th of October, another technique and performance skills. They will then opt to take Bree weekend will take place at Douglas Youth Centre on sessions in either accompanying & rhythm instruments Kensington Road. Inspired by the Feiséan nan Gael (e.g. guitar, piano, bodhran etc.); song-writing and movement in Scotland, Bree is a Manx Gaelic youth arts arranging or Manx dancing. All of the students will take movement for 11 to 16 year olds consisting of workshops in Manx Gaelic and learn to work in musical groups. music, language and dance. The first Bree [Manx for ‘vitality’] took place in October last year and proved to be The Bree workshops are led by local Manx musicians, not only educational, but fantastic fun for both students and dancers and language experts. They will take place tutors and a great place to make new friends, form new between 10am and 3.30pm on both days but will finish with bands and be really creative with Manx culture [see page 3 a concert for family and friends at the end of the second for a new song composed by a Bree member last year]. day from 3.30pm. Bree is organised and funded by the Since the last weekend festival of workshops, a monthly Manx Heritage Foundation and the Youth Service. youth music session has taken place at various venues around the Island. An application form is included at the end of this newsletter.