Humanism and Protestantism in Early Modern English Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOHN W. O·Malley, SJ JESUIT SCHOOLS and the HUMANITIES

JESUIT SCHOOLS AND THE HUMANITIES YESTERDAY AND TODAY -2+1:2·0$//(<6- ashington, D.C. 20036-5727 635,1* Jesuit Conference, Inc. 1016 16th St. NW Suite 400 W SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION, EFFECTIVE JANUARY 2015 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY The Seminar is composed of a number of Jesuits appointed from their prov- U.S. JESUITS inces in the United States. An annual subscription is provided by the Jesuit Conference for U.S. Jesuits living in the United The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice States and U.S. Jesuits who are still members of a U.S. Province but living outside the United of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and gathers current scholarly stud- States. ies pertaining to the history and ministries of Jesuits throughout the world. ALL OTHER SUBSCRIBERS It then disseminates the results through this journal. All subscriptions will be handled by the Business Office U.S.: One year, $22; two years, $40. (Discount $2 for Website payment.) The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, other Canada and Mexico: One year, $30; two years, $52. (Discount $2 for Website payment.) priests, religious, and laity. Hence, the studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclusively for them. Others who may find them Other destinations: One year: $34; two years, $60. (Discount $2 for Website payment.) helpful are cordially welcome to read them at: [email protected]/jesuits . ORDERING AND PAYMENT Place orders at www.agrjesuits.com to receive Discount CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR If paying by check - Make checks payable to: Seminar on Jesuit Spirituality Payment required at time of ordering and must be made in U.S. -

Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France

KNOWLEDGE COMMUNITIES Lynch Education in Late Medieval France Elementary and Grammar Sarah B. Lynch Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France Lyon, 1285-1530 Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France Knowledge Communities This series focuses on innovative scholarship in the areas of intellectual history and the history of ideas, particularly as they relate to the communication of knowledge within and among diverse scholarly, literary, religious, and social communities across Western Europe. Interdisciplinary in nature, the series especially encourages new methodological outlooks that draw on the disciplines of philosophy, theology, musicology, anthropology, paleography, and codicology. Knowledge Communities addresses the myriad ways in which knowledge was expressed and inculcated, not only focusing upon scholarly texts from the period but also emphasizing the importance of emotions, ritual, performance, images, and gestures as modalities that communicate and acculturate ideas. The series publishes cutting-edge work that explores the nexus between ideas, communities and individuals in medieval and early modern Europe. Series Editor Clare Monagle, Macquarie University Editorial Board Mette Bruun, University of Copenhagen Babette Hellemans, University of Groningen Severin Kitanov, Salem State University Alex Novikoff, Fordham University Willemien Otten, University of Chicago Divinity School Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France Lyon, 1285-1530 Sarah B. Lynch Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Aristotle Teaching in Aristotle’s Politiques, Poitiers, 1480-90. Paris, BnF, ms fr 22500, f. 248 r. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 986 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 902 5 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789089649867 nur 684 © Sarah B. -

Dissenters' Schools, 1660-1820

Dissenters' Schools, 1660-1820. HE contributions of nonconformity to education have seldom been recognized. Even historians of dissent T have rarely done more than mention the academies, and speak of them as though they existed chiefly to train ministers, which was but a very; small part o:f their function, almost incidental. Tbis side of the work, the tecbnical, has again been emphasized lately by Dr. Shaw in the " Cambridge History of Modern Literature," and by Miss Parker in her " Dissenting Academies in England ": it needs tberefore no further mention. A 'brief study of the wider contribution of dissent, charity schools, clay schools, boarding schools, has been laid before the members of our Society. An imperfect skeleton, naming and dating some of the schoolmasters, may be pieced together here. It makes no 'P'r·et·ence to be exhaustive; but it deliberately: excludes tutors who were entirely engaged in the work of pre paring men for the ministry, so as to illustrate the great work clone in general education. It incorporates an analysis of the. I 66 5 returns to the Bishop of Exeter, of IVIurch's history of the Presbyterian and General Baptist Churches in the West, of Nightingale's history of Lancashire Nonconformity (marked N), of Wilson's history of dissenting churches in and near London. The counties of Devon, Lancaste.r, and Middlesex therefore are well represented, and probably an analysis of any county dissenting history would reveal as good work being done in every rplace. A single date marks the closing of the school. Details about many will be found in the Transactions of the Congregational Historical Society, to which references are given. -

Records of Bristol Cathedral

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY’S PUBLICATIONS General Editors: MADGE DRESSER PETER FLEMING ROGER LEECH VOL. 59 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL EDITED BY JOSEPH BETTEY Published by BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 2007 1 ISBN 978 0 901538 29 1 2 © Copyright Joseph Bettey 3 4 No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, 5 electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information 6 storage or retrieval system. 7 8 The Bristol Record Society acknowledges with thanks the continued support of Bristol 9 City Council, the University of the West of England, the University of Bristol, the Bristol 10 Record Office, the Bristol and West Building Society and the Society of Merchant 11 Venturers. 12 13 BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 14 President: The Lord Mayor of Bristol 15 General Editors: Madge Dresser, M.Sc., P.G.Dip RFT, FRHS 16 Peter Fleming, Ph.D. 17 Roger Leech, M.A., Ph.D., FSA, MIFA 18 Secretaries: Madge Dresser and Peter Fleming 19 Treasurer: Mr William Evans 20 21 The Society exists to encourage the preservation, study and publication of documents 22 relating to the history of Bristol, and since its foundation in 1929 has published fifty-nine 23 major volumes of historic documents concerning the city. -

EDITORIAL UR April Number Last Year Recorded the Death of Dr

EDITORIAL UR April number last year recorded the death of Dr. _ Nightingale, our President, and M:r. H. A. Muddiman, O our Treasurer. This year we have the sorrowful duty of chronicling the death of the Rev. William Pierce, M.A., for many years ·Secretary of the Society and Dr. Nightingale's successor as President. The Congregational Historical Society has had no more devoted member and officer than M:r. Pierce, and it is difficult to imagine a meeting of the Society without him. He spent his life in the service of the Congregational churches and filled some noted pastorates, including those at New Court, Tollington Park, and Doddridge, Northampton, but he contrived to get through an immense amount of historical research-for many years he had a special table in the North Library of the British Museum. He has left three large volumes as evidence of his industry and his en thusiasm-An Historical Introduction to the Marprektte Tracts, The Marprel,ate Tracts, and John Penry. They are all valuable works, perhaps the reprint of the Tracts especially so, for it not only makes easy of access comparatively rare pamphlets, but it enables us to rebut at once and for always the extraordinary statements made time and again-by writers who obviously have never read the Tracts-to the effect that they are scurri lous, indecent, &c., &c. In this volume Pierce had not much opportunity to show his prejudices, and therefore the volume is his nearest approach to scientific history. The faculty which made him so delightful a companion-the vigour with which he held his views and denounced those who disagreed with him-sometimes led him from the impartiality which should mark the ideal historian : ~ he could damn a bishop he was perfectly happy! But his bias Is always obvious : it never misleads, and it will not prevent his work from living on and proving of service to all students .of Elizabethan religious history. -

The Church Militant: the American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92

The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Peter Walker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker This dissertation is a study of the loyalist Church of England clergy in the American Revolution. By reconstructing the experience and identity of this largely-misunderstood group, it sheds light on the relationship between church and empire, the role of religious pluralism and toleration in the American Revolution, the dynamics of loyalist politics, and the religious impact of the American Revolution on Britain. It is based primarily on the loyalist clergy’s own correspondence and writings, the records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, and the archives of the SPG (the Church of England’s missionary arm). The study focuses on the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies, where Anglicans formed a religious minority and where their clergy were overwhelmingly loyalist. It begins with the founding of the SPG in 1701 and its first forays into America. It then examines the state of religious pluralism and toleration in New England, the polarising contest over the proposed creation of an American bishop after the Seven Years’ War, and the role of the loyalist clergy in the Revolutionary War itself, focusing particularly on conflicts occasioned by the Anglican liturgy and Book of Common Prayer. -

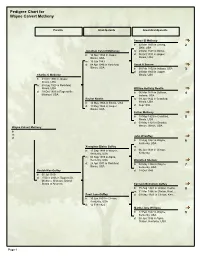

Pedigree Chart for Wayne Calvert Metheny

Pedigree Chart for Wayne Calvert Metheny Parents Grandparents Great-Grandparents Samuel B Matheny b: 22 Mar 1830 in Licking, 2 Ohio, USA Jonathan Calvert Metheney m: 29 Mar 1849 in Illinois b: 14 Nov 1860 in Jasper, d: 06 Oct 1891 in Jasper, Illinois, USA Illinois, USA m: 19 Jun 1883 d: 04 Apr 1943 in Rockford, Sarah A Sovern Illinois, USA b: 08 Feb 1832 in Indiana, USA 3 d: 29 Mar 1900 in Jasper, Charles C Metheny Illinois, USA b: 24 Oct 1906 in Jasper, Illinois, USA m: 08 Aug 1929 in Rockford, Illinois, USA William Holliday Newlin d: 19 Oct 1993 in Rogersville, b: 06 Mar 1818 in Sullivan, 4 Missouri, USA Indiana, USA Rachel Newlin m: 09 Jun 1842 in Crawford, b: 12 May 1866 in Illinois, USA Illinois, USA d: 11 May 1924 in Jasper, d: Sep 1892 Illinois, USA Esther Metheny b: 18 May 1823 in Crawford, 5 Illinois, USA d: 09 May 1928 in Decatur, Macon, Illinois, USA Wayne Calvert Metheny b: m: John W Guffey d: b: 18 Aug 1862 in Wayne, 6 Kentucky, USA Xenophon Blaine Guffey m: b: 17 Sep 1888 in Wayne, d: 06 Jun 1931 in Clinton, Kentucky, USA Kentucky m: 08 Sep 1909 in Alpha, Kentucky, USA Winnifred Shelton d: 24 Apr 1971 in Rockford, b: 02 May 1866 in Wayne, 7 Illinois, USA Kentucky, USA Beulah Mae Guffey d: 18 Oct 1946 b: 05 Jul 1910 d: 15 Dec 2006 in Rogersville, Webster, Missouri, United States of America Ephraim McCullom Guffey b: 15 Aug 1841 in Clinton, Kentu… 8 m: 31 Mar 1866 in Clinton, Kent… Pearl Jane Guffey d: 03 May 1923 in Clinton, Kent… b: 13 Jun 1891 in Clinton, Kentucky, USA d: 12 Feb 1923 Martha Jane Williams b: 12 Feb 1842 -

EDUCATION in LANCASHIRE and CHESHIRE, 1640-1660 Read 18

EDUCATION IN LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE, 1640-1660 BY C. D. ROGERS, M.A., M.ED. Read 18 November 1971 HE extraordinary decades of the Civil War and Interregnum, Twhen many political, religious, and economic assumptions were questioned, have been seen until recently as probably the greatest period of educational innovation in English history. Most modern writers have accepted the traditional picture of puritan attitudes and ideas, disseminated in numerous published works, nurtured by a sympathetic government, developing into an embryonic state system of education, a picture given added colour with details of governmental and private grants to schools.1 In 1967, however, J. E. Stephens, in an article in the British Journal of Educational Studies, suggested that detailed investigations into the county of York for the period 1640 to 1660 produced a far less admirable view of the general health of educational institutions, and concluded that 'if the success of the state's policy towards education is measured in terms of extension and reform, it must be found wanting'.2 The purpose of this present paper is twofold: to examine the same source material used by Stephens, to see whether a similar picture emerges for Lancashire and Cheshire; and to consider additional evidence to modify or support his main conclusions. On one matter there is unanimity. The release of the puritan press in the 1640s made possible a flood of books and pamphlets not about education in vacuo, but about society in general, and the role of the teacher within it. The authors of the idealistic Nova Solyma and Oceana did not regard education as a separate entity, but as a fundamental part of their Utopian structures. -

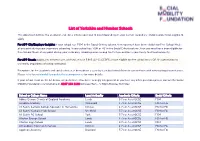

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Airedale Academy Wakefield 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints Catholic College Specialist in Humanities Kirklees 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints' Catholic High -

Chapter 2 – Late Middle Ages to Renaissance

INTERNATIONAL POLITICS AND WARFARE IN THE LATE MIDDLE AGES AND EARLY MODERN EUROPE A Bibliography of Diplomatic and Military Studies William Young Chapter 2 Late Middle Ages to Renaissance Italy (1337-1494) Europe (1337-1494) Allmand, Christopher Thomas, editor. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 7: c.1415-c.1500. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Aston, Margaret. The Fifteenth Century: The Prospect of Europe. Library of European Civilization series. London: Thames and Hudson, 1968. Cheyney, Edward P. The Dawn of a New Era, 1250-1453. The Rise of Modern Europe series. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1936. Fernández-Armesto, Felipe. Before Columbus: Exploration and Colonization from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, 1229-1492. The Middle Ages series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1987. Fowler, Kenneth. The Age of Plantagenet and Valois. London: Elek Press, 1967; New York: Exeter Books, 1980. Gilmore, Myron P. The World of Humanism, 1453-1517. The Rise of Modern Europe series. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1952. Hay, Denys. Europe in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. General History of Europe series. Second edition. London: Longman, 1989. Holmes, George. Europe: Hierarchy and Revolt, 1320-1450. Blackwell Classic Histories of Europe series. Second edition. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000. 1 Jones, Michael C.E., editor. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 6: c.1300-c.1415. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Mulgan, Catherine. The Renaissance Monarchies, 1469-1558. Cambridge Perspectives in History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Nicholas, David. The Transformation of Europe, 1300-1600. The Arnold History of Europe series. London: Arnold, 1999. Previté-Orton, Charles William and Zachary Nugent Brooke, editors. -

Guide to the PCE (Fifth Draft)

[FIFTH DRAFT TO THE] GUIDE TO THE Pure Cäm´-brìdîe Edition OF THE KING JAMES BIBLE. Matthew Verschuur ' Bible Protector Published by Bible Protector http://www.bibleprotector.com Copyright © Matthew William Verschuur 2010 Fifth Draft 2010 Published in Australia Typeface: Junius Family (freeware) The whole scripture is dited by God’s Spirit, thereby (as by his lively word) to instruct and rule the whole Church militant, till the end of the world. (KING JAMES I, Basilikon Doron, 1599.) we shall be traduced by Popish Persons at home or abroad, who therefore will malign us, because we are poor instruments to make God’s holy Truth to be yet more and more known unto the people (T. BILSON, The Epistle Dedicatory, 1611.) The true Succession is through the Spirit given in its measure. The Spirit is given for that use, ‘To make proper Speakers-forth of God’s eternal Truth;’ and that’s right Succession. (O. CROMWELL, Speech the First, 1653.) Dread sovereign, how much are we bound to heaven In daily thanks, that gave us such a prince; Not only good and wise, but most religious: One that, in all obedience, makes the church The chief aim of his honour; and, to strengthen That holy duty, out of dear respect, His royal self in judgment comes to hear The cause betwixt her and this great offender. Wherever the bright sun of heaven shall shine, His honour and the greatness of his name Shall be, and make new nations: he shall flourish, And, like a mountain cedar, reach his branches To all the plains about him: our children’s children Shall see this, and bless heaven. -

The Politics of Gossip in Early Virginia

"SEVERAL UNHANDSOME WORDS": THE POLITICS OF GOSSIP IN EARLY VIRGINIA Christine Eisel A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2012 Committee: Ruth Wallis Herndon, Advisor Timothy Messer-Kruse Graduate Faculty Representative Stephen Ortiz Terri Snyder Tiffany Trimmer © 2012 Christine Eisel All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ruth Wallis Herndon, Advisor This dissertation demonstrates how women’s gossip in influenced colonial Virginia’s legal and political culture. The scandalous stories reported in women’s gossip form the foundation of this study that examines who gossiped, the content of their gossip, and how their gossip helped shape the colonial legal system. Focusing on the individuals involved and recreating their lives as completely as possible has enabled me to compare distinct county cultures. Reactionary in nature, Virginia lawmakers were influenced by both English cultural values and actual events within their immediate communities. The local county courts responded to women’s gossip in discretionary ways. The more intimate relations and immediate concerns within local communities could trump colonial-level interests. This examination of Accomack and York county court records from the 1630s through 1680, supported through an analysis of various colonial records, family histories, and popular culture, shows that gender and law intersected in the following ways. 1. Status was a central organizing force in the lives of early Virginians. Englishmen punished women who gossiped according to the status of their husbands and to the status of the objects of their gossip. 2. English women used their gossip as a substitute for a formal political voice.