And Charles II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humanism and Calvinism for My Parents Humanism and Calvinism

Humanism and Calvinism For my parents Humanism and Calvinism Andrew Melville and the Universities of Scotland, 1560–1625 STEVEN J. REID University of Glasgow, UK First published 2011 by Ashgate Publishing Published 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © Steven J. Reid 2011 Steven J. Reid has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Reid, Steven J. Humanism and Calvinism : Andrew Melville and the universities of Scotland, 1560–1625. – (St Andrews studies in Reformation history) 1. Melville, Andrew, 1545–1622–Influence. 2. Universities and colleges – Scotland – History – 16th century. 3. Universities and colleges – Scotland – History – 17th century. 4. Church and college – Scotland – History – 16th century. 5. Church and college – Scotland – History – 17th century. 6. Reformation – Scotland. 7. Humanism – Scotland – History – 16th century. 8. Humanism – Scotland – History – 17th century. 9. University of St. Andrews – History. 10. Education, Higher – Europe – History. I. Title II. -

"For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh Mackay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2012 "For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland Andrew Phillip Frantz College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Frantz, Andrew Phillip, ""For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 480. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/480 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SO GOOD A CAUSE”: HUGH MACKAY, THE HIGHLAND WAR AND THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION IN SCOTLAND A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors is History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Andrew Phillip Frantz Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________ Nicholas Popper, Director _________________________________________ Paul Mapp _________________________________________ Simon Stow Williamsburg, Virginia April 30, 2012 Contents Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Chapter I The Origins of the Conflict 13 Chapter II Hugh MacKay and the Glorious Revolution 33 Conclusion 101 Bibliography 105 iii Figures 1. General Hugh MacKay, from The Life of Lieutenant-General Hugh MacKay (1836) 41 2. The Kingdom of Scotland 65 iv Acknowledgements William of Orange would not have been able to succeed in his efforts to claim the British crowns if it were not for thousands of people across all three kingdoms, and beyond, who rallied to his cause. -

Woodland Restoration in Scotland: Ecology, History, Culture, Economics, Politics and Change

Journal of Environmental Management 90 (2009) 2857–2865 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Environmental Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jenvman Woodland restoration in Scotland: Ecology, history, culture, economics, politics and change Richard Hobbs School of Environmental Science, Murdoch University, Murdoch, Western Australia 6150, Australia article info abstract Article history: In the latter half of the 20th century, native pine woodlands in Scotland were restricted to small remnant Received 15 January 2007 areas within which there was little regeneration. These woodlands are important from a conservation Received in revised form 26 October 2007 perspective and are habitat for numerous species of conservation concern. Recent developments have Accepted 30 October 2007 seen a large increase in interest in woodland restoration and a dramatic increase in regeneration and Available online 5 October 2008 woodland spread. The proximate factor enabling this regeneration is a reduction in grazing pressure from sheep and, particularly, deer. However, this has only been possible as a result of a complex interplay Keywords: between ecological, political and socio-economic factors. We are currently seeing the decline of land Scots Pine Pinus sylvestris management practices instituted 150–200 years ago, changes in land ownership patterns, cultural Woodland restoration revival, and changes in societal perceptions of the Scottish landscape. These all feed into the current Interdisciplinarity move to return large areas of the Scottish Highlands to tree cover. I emphasize the need to consider Grazing management restoration in a multidisciplinary framework which accounts not just for the ecology involved but also Land ownership the historical and cultural context. -

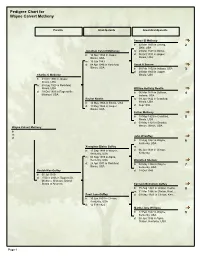

Pedigree Chart for Wayne Calvert Metheny

Pedigree Chart for Wayne Calvert Metheny Parents Grandparents Great-Grandparents Samuel B Matheny b: 22 Mar 1830 in Licking, 2 Ohio, USA Jonathan Calvert Metheney m: 29 Mar 1849 in Illinois b: 14 Nov 1860 in Jasper, d: 06 Oct 1891 in Jasper, Illinois, USA Illinois, USA m: 19 Jun 1883 d: 04 Apr 1943 in Rockford, Sarah A Sovern Illinois, USA b: 08 Feb 1832 in Indiana, USA 3 d: 29 Mar 1900 in Jasper, Charles C Metheny Illinois, USA b: 24 Oct 1906 in Jasper, Illinois, USA m: 08 Aug 1929 in Rockford, Illinois, USA William Holliday Newlin d: 19 Oct 1993 in Rogersville, b: 06 Mar 1818 in Sullivan, 4 Missouri, USA Indiana, USA Rachel Newlin m: 09 Jun 1842 in Crawford, b: 12 May 1866 in Illinois, USA Illinois, USA d: 11 May 1924 in Jasper, d: Sep 1892 Illinois, USA Esther Metheny b: 18 May 1823 in Crawford, 5 Illinois, USA d: 09 May 1928 in Decatur, Macon, Illinois, USA Wayne Calvert Metheny b: m: John W Guffey d: b: 18 Aug 1862 in Wayne, 6 Kentucky, USA Xenophon Blaine Guffey m: b: 17 Sep 1888 in Wayne, d: 06 Jun 1931 in Clinton, Kentucky, USA Kentucky m: 08 Sep 1909 in Alpha, Kentucky, USA Winnifred Shelton d: 24 Apr 1971 in Rockford, b: 02 May 1866 in Wayne, 7 Illinois, USA Kentucky, USA Beulah Mae Guffey d: 18 Oct 1946 b: 05 Jul 1910 d: 15 Dec 2006 in Rogersville, Webster, Missouri, United States of America Ephraim McCullom Guffey b: 15 Aug 1841 in Clinton, Kentu… 8 m: 31 Mar 1866 in Clinton, Kent… Pearl Jane Guffey d: 03 May 1923 in Clinton, Kent… b: 13 Jun 1891 in Clinton, Kentucky, USA d: 12 Feb 1923 Martha Jane Williams b: 12 Feb 1842 -

EDUCATION in LANCASHIRE and CHESHIRE, 1640-1660 Read 18

EDUCATION IN LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE, 1640-1660 BY C. D. ROGERS, M.A., M.ED. Read 18 November 1971 HE extraordinary decades of the Civil War and Interregnum, Twhen many political, religious, and economic assumptions were questioned, have been seen until recently as probably the greatest period of educational innovation in English history. Most modern writers have accepted the traditional picture of puritan attitudes and ideas, disseminated in numerous published works, nurtured by a sympathetic government, developing into an embryonic state system of education, a picture given added colour with details of governmental and private grants to schools.1 In 1967, however, J. E. Stephens, in an article in the British Journal of Educational Studies, suggested that detailed investigations into the county of York for the period 1640 to 1660 produced a far less admirable view of the general health of educational institutions, and concluded that 'if the success of the state's policy towards education is measured in terms of extension and reform, it must be found wanting'.2 The purpose of this present paper is twofold: to examine the same source material used by Stephens, to see whether a similar picture emerges for Lancashire and Cheshire; and to consider additional evidence to modify or support his main conclusions. On one matter there is unanimity. The release of the puritan press in the 1640s made possible a flood of books and pamphlets not about education in vacuo, but about society in general, and the role of the teacher within it. The authors of the idealistic Nova Solyma and Oceana did not regard education as a separate entity, but as a fundamental part of their Utopian structures. -

Hoofdstuk 7 Tweezijdige Puriteinse Vroomheid

VU Research Portal In God verbonden van Valen, L.J. 2019 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) van Valen, L. J. (2019). In God verbonden: De gereformeerde vroomheidsbetrekkingen tussen Schotland en de Nederlanden in de zeventiende eeuw, met name in de periode na de Restauratie (1660-1700). Labarum Academic. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Hoofdstuk 7 Tweezijdige puriteinse vroomheid Karakter van het Schots Puritanisme en parallellen tussen de Schotse Tweede Reformatie en de Nadere Reformatie Met de publicatie van ‘Christus de Weg, de Waarheid en het Leven’ komt ook naar voren dat deze heldere denker op het gebied van de kerkregering, deze bekwame en voorzichtige theoloog, deze ernstige en heftige polemist, een prediker en devotionele schrijver kon zijn met zulk een kracht en diepe spiritu- aliteit.1 I.B. -

Scotland and the Early Modern Naval Revolution, 1488-1603

Scotland and the Early Modern Naval Revolution, 1488-1603 by Sean K. Grant A Thesis Presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Sean K. Grant, October 2014 ABSTRACT SCOTLAND AND THE EARLY MODERN NAVAL REVOLUTION, 1488-1603 Sean Kevin Grant Advisor: University of Guelph, 2014 Professor E. Ewan By re-examining the circumstances surrounding the establishment and disestablishment of the Scots Navy, this thesis challenges existing scholarship which suggests that Scotland was neither an active participant in, or greatly impacted by, the early modern naval revolution. The Scots Navy did not disappear in the middle of the sixteenth century because Scotland no longer had need for a means of conducting maritime warfare, nor was a lack of fiscal capacity on the part of the Scottish state to blame, as has been suggested. In fact, the kingdom faced a constant series of maritime threats throughout the period, and these had compelled the Scots to accept the value of seapower and to embrace the technological innovations of the naval revolution. And as had occurred in other states impacted by the revolution, the Scottish fiscal system went through a structural transition that gave the Crown the capacity to acquire and maintain a permanent fleet. However, by mid-century the need for such a fleet had dissipated due to a shift in strategic focus which merged Crown and mercantile interests. This merger solved the principal-agent problem of military contracting – the dilemma that had led James IV to found the Navy in the first place – and this meant that Scottish maritime warfare could be conducted by privateers alone thereafter. -

The Politics of Gossip in Early Virginia

"SEVERAL UNHANDSOME WORDS": THE POLITICS OF GOSSIP IN EARLY VIRGINIA Christine Eisel A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2012 Committee: Ruth Wallis Herndon, Advisor Timothy Messer-Kruse Graduate Faculty Representative Stephen Ortiz Terri Snyder Tiffany Trimmer © 2012 Christine Eisel All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ruth Wallis Herndon, Advisor This dissertation demonstrates how women’s gossip in influenced colonial Virginia’s legal and political culture. The scandalous stories reported in women’s gossip form the foundation of this study that examines who gossiped, the content of their gossip, and how their gossip helped shape the colonial legal system. Focusing on the individuals involved and recreating their lives as completely as possible has enabled me to compare distinct county cultures. Reactionary in nature, Virginia lawmakers were influenced by both English cultural values and actual events within their immediate communities. The local county courts responded to women’s gossip in discretionary ways. The more intimate relations and immediate concerns within local communities could trump colonial-level interests. This examination of Accomack and York county court records from the 1630s through 1680, supported through an analysis of various colonial records, family histories, and popular culture, shows that gender and law intersected in the following ways. 1. Status was a central organizing force in the lives of early Virginians. Englishmen punished women who gossiped according to the status of their husbands and to the status of the objects of their gossip. 2. English women used their gossip as a substitute for a formal political voice. -

1The Question of Authority

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-62664-4 - Authority and Disorder in Tudor Times, 1485-1603 Paul Thomas Excerpt More information 1 The question of authority When Henry VII won the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, there was no outstanding evidence that this victory was more than the latest turn in fortune in the series of skirmishes and slaughters that had characterised the Wars of the Roses and had, indeed, affected politics for the best part of a century. The crown had repeatedly changed hands and it might well do so again. There were plenty of candidates to dispute Henry’s tenuous hold upon it. Where monarchy, the greatest authority in the land, had faltered and might well falter again, the absence of the ‘king’s peace’ had thrown both local authority and private, informal authority into turmoil. However, as the Tudor monarchs sought to establish themselves and regain royal authority, so the scope for government to impose its peace locally in the shires and also to interfere in private family relationships, in sex and in religion might also become extended. These opening chapters will first look at the state of formal authority in England in the late-fifteenth century, and then examine the local and personal inter- relationships that characterised respect, order and hierarchy at ground level. Ultimately, authority in a formal sense in late-medieval England derived from king, church and nobility. There was, by 1485, a distinct loosening of the bonds of Christendom with the pope’s formal authority at its head, as kings and countries sought to redefine their relationship with the papacy and define and extend their regional privileges. -

SCOTLAND and the BRITISH ARMY C.1700-C.1750

SCOTLAND AND THE BRITISH ARMY c.1700-c.1750 By VICTORIA HENSHAW A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The historiography of Scotland and the British army in the eighteenth century largely concerns the suppression of the Jacobite risings – especially that of 1745-6 – and the growing assimilation of Highland soldiers into its ranks during and after the Seven Years War. However, this excludes the other roles and purposes of the British army, the contribution of Lowlanders to the British army and the military involvement of Scots of all origin in the British army prior to the dramatic increase in Scottish recruitment in the 1750s. This thesis redresses this imbalance towards Jacobite suppression by examining the place of Scotland and the role of Highland and Lowland Scots in the British army during the first half of the eighteenth century, at a time of change fuelled by the Union of 1707 and the Jacobite rebellions of the period. -

The Highland Soldier in Georgia and Florida: a Case Study of Scottish Highlanders in British Military Service, 1739-1748

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2010 The Highland Soldier In Georgia And Florida: A Case Study Of Scottish Highlanders In British Military Service, 1739-1748 Scott Hilderbrandt University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Hilderbrandt, Scott, "The Highland Soldier In Georgia And Florida: A Case Study Of Scottish Highlanders In British Military Service, 1739-1748" (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4375. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4375 THE HIGHLAND SOLDIER IN GEORGIA AND FLORIDA: A CASE STUDY OF SCOTTISH HIGHLANDERS IN BRITISH MILITARY SERVICE, 1739-1748 by SCOTT ANDREW HILDERBRANDT B.A. University of Central Florida, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2010 ABSTRACT This study examined Scottish Highlanders who defended the southern border of British territory in the North American theater of the War of the Austrian Succession (1739-1748). A framework was established to show how Highlanders were deployed by the English between 1745 and 1815 as a way of eradicating radical Jacobite elements from the Scottish Highlands and utilizing their supposed natural superiority in combat. -

The Presbyterian Interpretation of Scottish History 1800-1914.Pdf

Graeme Neil Forsyth THE PRESBYTERIAN INTERPRETATION OF SCOTTISH HISTORY, 1800- 1914 Ph. D thesis University of Stirling 2003 ABSTRACT The nineteenth century saw the revival and widespread propagation in Scotland of a view of Scottish history that put Presbyterianism at the heart of the nation's identity, and told the story of Scotland's history largely in terms of the church's struggle for religious and constitutional liberty. Key to. this development was the Anti-Burgher minister Thomas M'Crie, who, spurred by attacks on Presbyterianism found in eighteenth-century and contemporary historical literature, between the years 1811 and 1819 wrote biographies of John Knox and Andrew Melville and a vindication of the Covenanters. M'Crie generally followed the very hard line found in the Whig- Presbyterian polemical literature that emerged from the struggles of the sixteenth and seventeenth century; he was particularly emphatic in support of the independence of the church from the state within its own sphere. His defence of his subjects embodied a Scottish Whig interpretation of British history, in which British constitutional liberties were prefigured in Scotland and in a considerable part won for the British people by the struggles of Presbyterian Scots during the seventeenth century. M'Crie's work won a huge following among the Scottish reading public, and spawned a revival in Presbyterian historiography which lasted through the century. His influence was considerably enhanced through the affinity felt for his work by the Anti- Intrusionists in the Church of Scotland and their successorsin the Free Church (1843- 1900), who were particularly attracted by his uncompromising defence of the spiritual independence of the church.