John Milton's “Of Education” and Lessons for the 21St Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

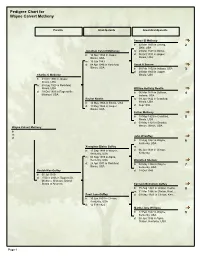

Pedigree Chart for Wayne Calvert Metheny

Pedigree Chart for Wayne Calvert Metheny Parents Grandparents Great-Grandparents Samuel B Matheny b: 22 Mar 1830 in Licking, 2 Ohio, USA Jonathan Calvert Metheney m: 29 Mar 1849 in Illinois b: 14 Nov 1860 in Jasper, d: 06 Oct 1891 in Jasper, Illinois, USA Illinois, USA m: 19 Jun 1883 d: 04 Apr 1943 in Rockford, Sarah A Sovern Illinois, USA b: 08 Feb 1832 in Indiana, USA 3 d: 29 Mar 1900 in Jasper, Charles C Metheny Illinois, USA b: 24 Oct 1906 in Jasper, Illinois, USA m: 08 Aug 1929 in Rockford, Illinois, USA William Holliday Newlin d: 19 Oct 1993 in Rogersville, b: 06 Mar 1818 in Sullivan, 4 Missouri, USA Indiana, USA Rachel Newlin m: 09 Jun 1842 in Crawford, b: 12 May 1866 in Illinois, USA Illinois, USA d: 11 May 1924 in Jasper, d: Sep 1892 Illinois, USA Esther Metheny b: 18 May 1823 in Crawford, 5 Illinois, USA d: 09 May 1928 in Decatur, Macon, Illinois, USA Wayne Calvert Metheny b: m: John W Guffey d: b: 18 Aug 1862 in Wayne, 6 Kentucky, USA Xenophon Blaine Guffey m: b: 17 Sep 1888 in Wayne, d: 06 Jun 1931 in Clinton, Kentucky, USA Kentucky m: 08 Sep 1909 in Alpha, Kentucky, USA Winnifred Shelton d: 24 Apr 1971 in Rockford, b: 02 May 1866 in Wayne, 7 Illinois, USA Kentucky, USA Beulah Mae Guffey d: 18 Oct 1946 b: 05 Jul 1910 d: 15 Dec 2006 in Rogersville, Webster, Missouri, United States of America Ephraim McCullom Guffey b: 15 Aug 1841 in Clinton, Kentu… 8 m: 31 Mar 1866 in Clinton, Kent… Pearl Jane Guffey d: 03 May 1923 in Clinton, Kent… b: 13 Jun 1891 in Clinton, Kentucky, USA d: 12 Feb 1923 Martha Jane Williams b: 12 Feb 1842 -

Saturn As the “Sun of Night” in Ancient Near Eastern Tradition ∗

Saturn as the “Sun of Night” in Ancient Near Eastern Tradition ∗ Marinus Anthony van der Sluijs – Seongnam (Korea) Peter James – London [This article tackles two issues in the “proto-astronomical” conception of the planet Saturn, first attested in Mesopotamia and followed by the Greeks and Hindus: the long-standing problem of Saturn’s baffling association with the Sun; and why Saturn was deemed to be “black”. After an extensive consideration of explanations offered from the 5th century to the 21st, as well as some new “thought experiments”, we suggest that Saturn’s connection with the Sun had its roots in the observations that Saturn’s course appears to be the steadiest one among the planets and that its synodic period – of all the planets – most closely resembles the length of the solar year. For the black colour attributed to Saturn we propose a solution which is partly lexical and partly observational (due to atmospheric effects). Finally, some thoughts are offered on the question why in Hellenistic times some considered the “mock sun” Phaethon of Greek myth to have been Saturn]. Keywords: Saturn, planets, Sun, planet colour. 1. INTRODUCTION Since the late 19th century scholars have been puzzled by a conspicuous peculiarity in the Babylonian nomenclature for the planet Saturn: a number of texts refer to Saturn as the “Sun” ( dutu/20 or Šamaš ), instead of its usual astronomical names Kayam ānu and mul UDU.IDIM. 1 This curious practice was in vogue during the period c. 750-612 BC 2 and is not known from earlier periods, with a single possible exception, discussed below. -

EDUCATION in LANCASHIRE and CHESHIRE, 1640-1660 Read 18

EDUCATION IN LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE, 1640-1660 BY C. D. ROGERS, M.A., M.ED. Read 18 November 1971 HE extraordinary decades of the Civil War and Interregnum, Twhen many political, religious, and economic assumptions were questioned, have been seen until recently as probably the greatest period of educational innovation in English history. Most modern writers have accepted the traditional picture of puritan attitudes and ideas, disseminated in numerous published works, nurtured by a sympathetic government, developing into an embryonic state system of education, a picture given added colour with details of governmental and private grants to schools.1 In 1967, however, J. E. Stephens, in an article in the British Journal of Educational Studies, suggested that detailed investigations into the county of York for the period 1640 to 1660 produced a far less admirable view of the general health of educational institutions, and concluded that 'if the success of the state's policy towards education is measured in terms of extension and reform, it must be found wanting'.2 The purpose of this present paper is twofold: to examine the same source material used by Stephens, to see whether a similar picture emerges for Lancashire and Cheshire; and to consider additional evidence to modify or support his main conclusions. On one matter there is unanimity. The release of the puritan press in the 1640s made possible a flood of books and pamphlets not about education in vacuo, but about society in general, and the role of the teacher within it. The authors of the idealistic Nova Solyma and Oceana did not regard education as a separate entity, but as a fundamental part of their Utopian structures. -

Curriculum Vitae: John Patrick Considine June 2021

Curriculum Vitae: John Patrick Considine June 2021 Current personal details Current Position Professor, Department of English, University of Alberta E-mail [email protected] Previous positions held 2004–2010 Associate Professor, Department of English, University of Alberta 2000–2004 Assistant Professor, Department of English, University of Alberta. 1996–2000 Adjunct Professor and Lecturer, Department of English, University of Alberta. 1995–1996 Assistant Editor, Oxford English Dictionary. Degrees granted 1995 D.Phil. in English Language and Literature, Oxford University: ‘The Humanistic Antecedents of the Early Seventeenth-Century English Character-Books.’ 1993 M.A. in English Language and Literature, Oxford University. 1989 B. A. in English Language and Literature, Oxford University. Awards and honours 2017 J. Gordin Kaplan Award for Excellence in Research, University of Alberta 2015 Killam Annual Professorship, University of Alberta 2015– Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London 2012 Faculty of Arts Undergraduate Teaching Award, University of Alberta. 2000 Faculty of Arts Sessional Instructor Teaching Award, University of Alberta Other Academic Activities 2020– Editorial board, International Journal of Lexicography 2018–20 Associate Editor, International Journal of Lexicography 2015– Editorial board, Language and History 2013–20 Editorial board, Renaissance and Reformation 2011–14 Editorial board, Studies in the History of the Language Sciences (John Benjamins book series) 2010–14 Associate Editor, Historiographia Linguistica. 2005–2009 English-language book review editor (jointly with Sylvia Brown) of Renaissance and Reformation. 1996– Consultant in early modern English and Latin to the Oxford English Dictionary. Publications Monographs Sixteenth-century English dictionaries: vol. 1 of Dictionaries in the English-speaking world, 1500-1800. -

Claudius Salmasius and the Deadness of Neo-Latin

CLAUDIUS SALMASIUS AND THE DEADNESS OF NEO-LATIN John Considine 1. “Eratosthenes seculi nostri”: Salmasius’ reputation Claudius Salmasius (1588–1653) is one of those neo-Latin authors whom hardly anybody seems to read: in the two volumes of IJsewijn and Sacré’s Companion to Neo-Latin Studies, he is mentioned only once, in passing.1 No full-scale biography of him has ever been published.2 This is strange when one considers how highly he was praised in his own century. To Hugo Grotius, he was “Vir infinitae lectionis”; to Johannes Fredericus Gronovius, “Varro et Eratosthenes seculi nostri.”3 Salmasius’ reputation has declined: the afterlife of Gronovius’ comparison makes the point. “He certainly deserved his reputation for learning as the Eratosthenes of his time,” remarks Rudolf Pfeiffer, directing the reader in a footnote to the final page of his own earlier account of Eratosthenes.4 There, Eratosthenes is called “one of the greatest scholars of all times,” but his nicknames “beta” (implying “second-best at everything”) and “the pentathlete” (implying “jack of all trades”) are also quoted.5 The paradox by which scholars of exceptionally broad learning are less celebrated than their more limited contemporaries has affected the repu- tations of other philologists. Modern studies of Salmasius concentrate on one aspect or another of his intellectual life, such as his work on language or on classical philology.6 But there are other factors at work in the case of 1 Jozef IJsewijn, Companion to Neo-Latin Studies ed. 2 (second volume with Dirk Sacré) (Leuven, 1990–1998), 2: 286. 2 The fullest biographical treatment in English appears to be Kathryn A. -

The Politics of Gossip in Early Virginia

"SEVERAL UNHANDSOME WORDS": THE POLITICS OF GOSSIP IN EARLY VIRGINIA Christine Eisel A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2012 Committee: Ruth Wallis Herndon, Advisor Timothy Messer-Kruse Graduate Faculty Representative Stephen Ortiz Terri Snyder Tiffany Trimmer © 2012 Christine Eisel All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ruth Wallis Herndon, Advisor This dissertation demonstrates how women’s gossip in influenced colonial Virginia’s legal and political culture. The scandalous stories reported in women’s gossip form the foundation of this study that examines who gossiped, the content of their gossip, and how their gossip helped shape the colonial legal system. Focusing on the individuals involved and recreating their lives as completely as possible has enabled me to compare distinct county cultures. Reactionary in nature, Virginia lawmakers were influenced by both English cultural values and actual events within their immediate communities. The local county courts responded to women’s gossip in discretionary ways. The more intimate relations and immediate concerns within local communities could trump colonial-level interests. This examination of Accomack and York county court records from the 1630s through 1680, supported through an analysis of various colonial records, family histories, and popular culture, shows that gender and law intersected in the following ways. 1. Status was a central organizing force in the lives of early Virginians. Englishmen punished women who gossiped according to the status of their husbands and to the status of the objects of their gossip. 2. English women used their gossip as a substitute for a formal political voice. -

1The Question of Authority

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-62664-4 - Authority and Disorder in Tudor Times, 1485-1603 Paul Thomas Excerpt More information 1 The question of authority When Henry VII won the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, there was no outstanding evidence that this victory was more than the latest turn in fortune in the series of skirmishes and slaughters that had characterised the Wars of the Roses and had, indeed, affected politics for the best part of a century. The crown had repeatedly changed hands and it might well do so again. There were plenty of candidates to dispute Henry’s tenuous hold upon it. Where monarchy, the greatest authority in the land, had faltered and might well falter again, the absence of the ‘king’s peace’ had thrown both local authority and private, informal authority into turmoil. However, as the Tudor monarchs sought to establish themselves and regain royal authority, so the scope for government to impose its peace locally in the shires and also to interfere in private family relationships, in sex and in religion might also become extended. These opening chapters will first look at the state of formal authority in England in the late-fifteenth century, and then examine the local and personal inter- relationships that characterised respect, order and hierarchy at ground level. Ultimately, authority in a formal sense in late-medieval England derived from king, church and nobility. There was, by 1485, a distinct loosening of the bonds of Christendom with the pope’s formal authority at its head, as kings and countries sought to redefine their relationship with the papacy and define and extend their regional privileges. -

Seventeenth-Century News NEO-LATIN NEWS

180 seventeenth-century news NEO-LATIN NEWS Vol. 60, Nos. 3 & 4. Jointly with SCN. NLN is the offi cial publica- tion of the American Association for Neo-Latin Studies. Edited by Craig Kallendorf, Texas A&M University; Western European Editor: Gilbert Tournoy, Leuven; Eastern European Editors: Jerzy Axer, Barbara Milewska-Wazbinska, and Katarzyna Tomaszuk, Centre for Studies in the Classical Tradition in Poland and East- Central Europe, University of Warsaw. Founding Editors: James R. Naiden, Southern Oregon University, and J. Max Patrick, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and Graduate School, New York University. ♦ Bessarion Scholasticus: A Study of Cardinal Bessarion’s Latin Library. By John Monfasani. Byzantios: Studies in Byzantine His- tory and Civilization, 3. Turnhout: Brepols, 2011. XIV + 306 pp. 65 euros. Bessarion fi rst made a name for himself as a spokesman for the Greek side at the Council of Ferrara-Florence in 1438-39. He became a cardinal in the western church and was a serious candidate for the papacy more than once. Bessarion amassed an enormous library that was especially famous for its collection of Greek manuscripts, then left it to the Republic of Venice with the intention of making it the core of what is now the Biblioteca Marciana. He patronized humanist scholars and writers and was himself Italy’s leading Platonist before Marsilio Ficino, with his In calumniatores Platonis being an important text in the Renaissance Plato-Aristotle controversy. He died in 1472, well known and well respected. Th is is the Bessarion we all think we know, but the Bessarion who emerges from the pages of Bessarion Scholasticus stubbornly refuses to be constrained within these limits. -

The Short History of Science

PHYSICS FOUNDATIONS SOCIETY THE FINNISH SOCIETY FOR NATURAL PHILOSOPHY PHYSICS FOUNDATIONS SOCIETY THE FINNISH SOCIETY FOR www.physicsfoundations.org NATURAL PHILOSOPHY www.lfs.fi Dr. Suntola’s “The Short History of Science” shows fascinating competence in its constructively critical in-depth exploration of the long path that the pioneers of metaphysics and empirical science have followed in building up our present understanding of physical reality. The book is made unique by the author’s perspective. He reflects the historical path to his Dynamic Universe theory that opens an unparalleled perspective to a deeper understanding of the harmony in nature – to click the pieces of the puzzle into their places. The book opens a unique possibility for the reader to make his own evaluation of the postulates behind our present understanding of reality. – Tarja Kallio-Tamminen, PhD, theoretical philosophy, MSc, high energy physics The book gives an exceptionally interesting perspective on the history of science and the development paths that have led to our scientific picture of physical reality. As a philosophical question, the reader may conclude how much the development has been directed by coincidences, and whether the picture of reality would have been different if another path had been chosen. – Heikki Sipilä, PhD, nuclear physics Would other routes have been chosen, if all modern experiments had been available to the early scientists? This is an excellent book for a guided scientific tour challenging the reader to an in-depth consideration of the choices made. – Ari Lehto, PhD, physics Tuomo Suntola, PhD in Electron Physics at Helsinki University of Technology (1971). -

Controversy, Competition, and Insult in the Republic of Letters

REVIEW ESSAY Controversy, Competition, and Insult in the Republic of Letters Kai Bremer and Carlos Spoerhase, eds., “Theologisch-polemisch-poetische Sachen”: Gelehrte Polemik im 18. Jahrhundert. Zeitsprünge: Forschungen zur Frühen Neuzeit 19. Frankfurt: Klostermann, 2015. Pp. viii1364. €49.00 (paper). Kai Bremer and Carlos Spoerhase, eds., Gelehrte Polemik: Intellektuelle Konfliktvers- chärfungen um 1700. Zeitsprünge: Forschungen zur Frühen Neuzeit 15. Frankfurt: Klostermann, 2011. Pp. iv1440. €40.00 (paper). Sari Kivisto, The Vices of Learning: Morality and Knowledge at Early Modern Universities. Leiden: Brill, 2014. Pp. 304. US$163.00 (paper). t might seem straightforward to suggest that quarrels have pervaded the European Ihistory of humanities. From the Christian world chronologies of Africanus and Eu- sebius through the medieval nominalist and realist philosophers to the battle of the classical philologists in nineteenth-century Germany, humanists’ passion to advance sweeping views has often accompanied authentic innovation in their disciplines. Ac- tually, in the books under review, polemic and hostility come as a major change in our received picture of the Republic of Letters, the prolific international community of scholars that flourished across Europe from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. We have been far more accustomed to hear of these humanists as sociable and polite citizens of an invisible and somewhat utopian state. In these new histories of conflict, and in the vigorous rise of similar scholarship in recent years, we can repeat John Milton’s discovery in Paradise Lost: Satan is a more interesting hero than Adam. For the last three decades, a highly stable discussion centered in France has shown how the Republic of Letters worked.1 The question arises because humanists often operated outside formal institutions, and their relationships often crossed national and religious boundaries. -

The Modern in a Classical Perspective

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy The Modern in a Classical Perspective An Analytic Study of the Relation Between Character and Rhetorical Development in the Speeches of Milton’s Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained in Comparison to Virgil’s Aeneid Paper submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of "Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels-Latijn" Matthias Devreese Academic year 2015-2016 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Wim Verbaal Likewise Rhetoric captures the minds of men and so pleasantly draws them after her in chains those who are enticed, that at one time she is able to move to pity, at another to transport into hatred, again to kindle to warlike ardor, and then to exalt to contempt of death. - John Milton, transl. by Bromley Smith ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis in written in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of "Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels-Latijn". However, before diving deeper into the research part of it, I would like to extend my sincere thanks and appreciation to a number of people for their support and motivation while writing this thesis. Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Prof. Dr. Wim Verbaal, for providing background knowledge and general guidance throughout this year. His supervision was most helpful in adjusting the content of this paper where adjustment was needed. His feedback and overall advice have given me the opportunity to enhance both my writing and research skills, and to improve this thesis to its current state. Secondly, I would like to express gratitude to my friends and fellow students, Joram Van Acker and Steffie Van Neste, for rereading this paper and improving its comprehensibility. -

Seiichiro Ito (Ohtsuki City College, Japan)

Neighbour country, Holland: an ideal model to follow, or just an enemy? Seiichiro Ito (Ohtsuki City College, Japan) Abstract In the seventeenth century, particularly in its first half, the English pamphleteers often argued that the English should learn the manner of herring fishing from the Dutch and it is essential for the success of the English trade. While they tended to focus on the technical aspects of fishing business, around mid-century some pamphleteers showed their interest in the Dutch society as a whole. They shared the list of their merits to learn from the Dutch model, such as the management of trade, low customs, low interest rates, and banking. Over the Navigation Act of 1651, some were supportive and some were against, but both sides shared the same images of Holland. From around 1670 the styles of the discourses of the pamphleteers who discuss trade also changed. They got more analytical and systematic. Roger Coke was an example. Introduction In 1651 where England was stepping into the way to the war with the Dutch, Thomas Hobbes was also one of those who had a complex feeling against them. Hobbes expresses it as follows: ‘I doubt not, but many men, have been contented to see the late troubles in England, out of an imitation of the Low Countries; supposing there needed no more to grow rich, than to change, as they had done, the forme of their Government.’ (Hobbes, Leviathan, 1991, p. 225.) Hobbes here shows one of reasons why the Common-wealth would lead to its dissolution. The example of the government of a neighbour country ‘disposeth men to alteration of the forme already setled’, just as false doctrines do.