Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020

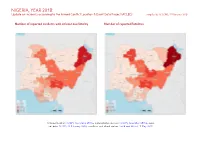

NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 22 February 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 705 566 2853 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 474 373 2470 Development of conflict incidents from 2009 to 2018 2 Protests 427 3 3 Riots 213 61 154 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 117 3 4 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 100 84 759 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 2036 1090 6243 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2009 to 2018 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). 2 NIGERIA, YEAR 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Integrated Geophysical Investigation of a Suspected Spring in Igbokoran, Ikare-Akoko, Southwestern Nigeria

IOSR Journal of Applied Geology and Geophysics (IOSR-JAGG) e-ISSN: 2321–0990, p-ISSN: 2321–0982.Volume 3, Issue 5 Ver. I (Sep. - Oct. 2015), PP 83-91 www.iosrjournals.org Integrated Geophysical Investigation of a Suspected Spring in Igbokoran, Ikare-Akoko, Southwestern Nigeria Onoja S.O1, Osifila A.J2, 1(Department of Physics, kogi State University Anyigba,Nigeria) 2(Department of Applied Geophysics, Federal University of Technology Akure, Nigeria) Abstract: An integrated geophysical investigation involving self potential (SP), very low frequency electromagnetic (VLF-EM) and electrical resistivity methods (VES) were conducted around a suspected spring in Igbokoran, Ikare Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria in other to understand the nature of the spring as well as evaluate the feasibility of ground water development in the area. Three geophysical traverses of length 240m each were established in the study area in approximately E-W direction. VLF-EM measurements with station spacing of 10m was used as reconnaissance to delineate conductive zones between 70-160m along traverse 1, 80-170 m along traverse 2 and 60-180m along traverse 3.This was then followed by a total of six (6) VES stations along traverses 2 and 3 using the Schlumberger array with electrode spacing (AB/2) ranging from 1 to 150m. Three geoelectric layers (Top layer, weathered layer, and fresh basement) were delineated along all traverses and a suspected fractured basement along traverse three .The Self Potential (SP) measurements were carried out at 5m electrode separation employing the total fixed base array. SP profiles were generated which show anomalies with short negative amplitudes some of which coincides with the spring zone. -

The Use of Nigerian Pidgin in Media Adverts

International Journal of English Linguistics; Vol. 4, No. 2; 2014 ISSN 1923-869X E-ISSN 1923-8703 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Use of Nigerian Pidgin in Media Adverts Joseph Babasola Osoba1 1 Department of English, University of Lagos, Akoka, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria Correspondence: Joseph Babasola Osoba, Department of English, University of Lagos, Akoka, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: November 27, 2013 Accepted: February 1, 2014 Online Published: March 26, 2014 doi:10.5539/ijel.v4n2p26 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v4n2p26 Abstract The use of Nigerian Pidgin seems to have gained a wider currency since Nigeria’s independence in 1960. Among the educated and barely educated, the pidgin is used profusely in many spheres of life, especially in informal situations. In the mass media (television, radio, magazines and newspapers), schools, higher institutions of learning, government offices, etc., pidgin discourse abounds. In fact, despite the fact that it is not yet an official lingua franca in the country, it is a daily phenomenon in every day affair of an average Nigerian. The nature of Nigerian Pidgin, its easy mode of acquisition as well as the multilingual background of Nigerians may have been responsible for its present status and functions. In the light of the above, I am interested in how meaning is assigned to a piece of pidgin discourse, especially an advert in Nigerian Pidgin. Thus the goal of this paper is to establish how pidgin adverts communicate the intended meaning of their advertisers and how the audiences perceive them through an application of “Presupposition” and “Implicature” as conceptual or theoretical tools. -

Journal of African Studies and Sustainable Development

Journal of African Studies and Sustainable Development. ISSN: 2630-7065 (Print) 2630-7073 (e). Vol. 3 No. 3. 2020 Association for the Promotion of African Studies ENGLISH LANGUAGE: AN IMPERATIVE TOOL FOR ETHNO- LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL UNITY IN NIGERIA Ogunnaike Jimi, Ph.D. Department of English Studies Tai Solarin University of Education Ijagun, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria [email protected] DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.12616.55046 & Adenuga, F. T. Ph.D Department of English Studies Tai Solarin University of Education Ijagun, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria [email protected] DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.12616.55046 Abstract With her more than one hundred and fifty million people, Nigeria is not only densely populated but equally ethnolinguistically and multiculturally diverse in nature. Before the arrival of the British colonialists, Nigeria used to be an homogeneous entity with various indigenous or local languages. The unification of these various entities in 1914 by the British government brought Nigeria together as an homogeneous entity with the name called "Nigeria" having two broad divisions, tagged the Northern and Southern protectorates. The two protectorates were also dominated by three major indigenous languages -Hausa in the North while Igbo and Yoruba were in the Eastern and Western parts of the Southern protectorate respectively. These three major indigenous languages notwithstanding, there are at the moment, more than two hundred and fifty local or indigenous languages spoken all over the nation with their different cultures. Nigeria is being united through the adoption and use of the English language which the European colonialists imposed on her and her people. -

The Sahel and West Africa Club

2011 – 2012 WORK PRIORITIES GOVERNANCE THE CLUB AT A GLANCE SAHEL AND WEST AFRICA Club he Strategy and Policy Group (SPG) brings together Club Members twice a year Secretariat 1973. Extreme drought in the Sahel; creation of the “Permanent Inter-State Committee for Drought Food security: West African Futures Tto defi ne the Club’s work priorities and approve the programme of work and Control in the Sahel” (CILSS). The Club’s work focuses on settlement trends and market dynamics, analysing how budget as well as activity and fi nancial reports. Members also ensure the Club’s these two factors impact agricultural activities and food security conditions in smooth functioning through their fi nancial contributions (minimum contribution 1976. Creation of the “Club du Sahel” at the initiative of CILSS and some OECD member countries aiming West Africa. Building on a literature review and analyses of existing information, agreed upon by consensus) and designate the Club President. The position is at mobilising the international community in support of the Sahel. it questions the coherence of data currently used for policy and strategy design. It currently held by Mr. François-Xavier de Donnea, Belgian Minister of State. Under Secrétariat du also highlights the diffi culty of cross-country comparisons, which explains why the management structure of the OECD Secretariat for Global Relations, the SWAC THE SAHEL 1984. Another devastating drought; creation of the “Food Crisis Prevention Network” (RPCA) at the DU SAHEL ET DE it is almost impossible to construct a precise description of regional food security Secretariat is in charge of implementing the work programme. -

A History of Domestic Animals in Northeastern Nigeria

A history of domestic animals in Northeastern Nigeria Roger M. BLENCH * PREFATORY NOTES Acronyms, toponyms, etc. Throughout this work, “Borna” and “Adamawa” are taken ta refer to geographical regions rather than cunent administrative units within Nigeria. “Central Africa” here refers to the area presently encompas- sed by Chad, Cameroun and Central African Republic. Orthography Since this work is not wrîtten for specialised linguists 1 have adopted some conventions to make the pronunciation of words in Nigerian lan- guages more comprehensible to non-specialists. Spellings are in no way “simplified”, however. Spellings car-rbe phonemic (where the langua- ge has been analysed in depth), phonetic (where the form given is the surface form recorded in fieldwork) or orthographie (taken from ear- lier sources with inexplicit rules of transcription). The following table gives the forms used here and their PA equivalents: This Work Other Orthographie IPA 11989) j ch tî 4 d3 zl 13 hl, SI Q Words extracted from French sources have been normalised to make comparison easier. * Anthropologue, African Studies Cenfer, Universify of Cambridge 15, Willis Road, Cambridge CB7 ZAQ, Unifed Kingdom. Cah. Sci. hum. 37 (1) 1995 : 787-237 182 Roger BLENCH Tone marks The exact significance of tone-marks varies from one language to ano- ther and 1 have used the conventions of the authors in the case of publi- shed Ianguages. The usual conventions are: High ’ Mid Unmarked Low \ Rising ” Falling A In Afroasiatic languages with vowel length distinctions, only the first vowel of a long vowel if tone-marked. Some 19th Century sources, such as Heinrich Barth, use diacritics to mark stress or length. -

Reconstructing Benue-Congo Person Marking II

Kirill Babaev Russian State University for the Humanities Reconstructing Benue-Congo person marking II This paper is the second and last part of a comparative analysis of person marking systems in Benue-Congo (BC) languages, started in (Babaev 2008, available online for reference). The first part of the paper containing sections 1–2 gave an overview of the linguistic studies on the issue to date and presented a tentative reconstruction of person marking in the Proto- Bantoid language. In the second part of the paper, this work is continued by collecting data from all the other branches of BC and making the first step towards a reconstruction of the Proto-BC system of person marking. Keywords: Niger-Congo, Benue-Congo, personal pronouns, comparative research, recon- struction, person marking. The comparative outlook of person marking systems in the language families lying to the west of the Bantoid-speaking area is a challenge. These language stocks (the East BC families of Cross River, Plateau, Kainji and Jukunoid, and the West BC including Edoid, Nupoid, Defoid, Idomoid, Igboid and a few genetically isolated languages of Nigeria) are still far from being sufficiently studied or even described, and the amount of linguistic data for many of them re- mains quite scarce. In comparison with the Bantu family which has enjoyed much attention from comparative linguists within the last decades, there are very few papers researching the other subfamilies of BC from a comparative standpoint. This is especially true for studies in morphology, including person marking. The aim here is therefore to make the very first step towards the comparative analysis and reconstruction of person markers in BC. -

African Language Offerings

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA AFRICA CENTER African Language Offerings Stimulate your brain with unique African sounds and cultures by learning any of the following languages • Amharic (Ethiopia) • Chichewa (Malawi) • Igbo (Southeastern Nigeria) • Malagasy (Madagascar) • Setswana (Botswana and South Africa) • Sudanese Arabic (Sudan) • Swahili (Tanzania, Kenya, Comoro islands, Rwanda, and Somalia) • Tigrinya (Eritrea and Ethiopia) • Twi (Ghana and Ivory Coast) • Wolof (Senegal, Gambia, and Mauritania) • Yoruba (Southwestern Nigeria, Togo, Benin, and Sierra Leone) • Zulu (South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Swaziland and Malawi Fulfill your language requirement Fulfill your minor or major in African Studies Enhance your cultural aptitude with Study Abroad programs in Ghana, Senegal, Tanzania, Kenya, and South Africa For more information contact the African Language Program Director, Dr. Audrey N. Mbeje: Tel. (215) 898-4299 or email [email protected] Website: http://www.africa.upenn.edu/afl Foreign Language and Area Studies (FLAS) Fellowship! http://www.africa.upenn.edu/afl/FLAS.htm Africa Center University of Pennsylvania 647 Williams Hall Philadelphia, PA 19104-2615 Phone:(215)898-6971 Language Descriptions: Speakers and Places Amharic —Is the national language of Ethiopia and is spoken by around 12 million people as their mother- tongue and by many more as a second language. Though only one of seventy or so languages spoken in Ethi- opia, Amharic has been the language of the court and the dominant population group in Highland Ethiopia. Amharic belongs to the Semitic family of languages and as such is related to Arabic and Hebrew. Whilst many of the grammatical forms is reminiscent of the latter languages, the sentence structure (syntax) is very different and has more in common with the non-Semitic languages of Ethiopia. -

Hydro-Geochemical Evaluation of Groundwater Quality in Akoko North West Local Government Area of Ondo State, Nigeria

ISSN = 1980-993X – doi:10.4136/1980-993X www.ambi-agua.net E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (12) 3625-4212 Hydro-geochemical evaluation of groundwater quality in Akoko North West local government area of Ondo State, Nigeria (http://dx.doi.org/10.4136/ambi-agua.851) Temitope D. T. Oyedotun1; Opeyemi Obatoyinbo2 1Department of Geography and Planning Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences, Adekunle Ajasin University, P. M. B. 001, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria. e-mail: [email protected]; 2Department of Geology, Faculty of Science, Adekunle Ajasin University, P. M. B. 001, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria. e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT A sudden geometric increase in population of Akoko North West Local Government Area of Ondo State has led to an increase in demand for water and harnessing of subsurface water reserve. A total of twenty six water samples obtained from both boreholes and hand-dug wells were analyzed for their physico-chemical characteristics with the aim of assessing their quality, usability and also to determine the level of their contamination in the local government which is dominated by granite gneisses, charnockites, and augen gneisses as the main rock types. The following physico-chemical properties were analyzed for in the samples collected: electrical conductivity (EC), pH, total alkalinity (TA), total dissolved solids (TDS), total suspended solids (TSS), acid neutralizing capacity (ANC) with major cations (Na+, 2+ 2+ 3- - 3- 2+ 2+ + + Mg , Ca ), anions (PO4 , HCO3 , SO4 ) and several heavy metals -

Chinyere Ohiri-Aniche. Reconstructing the Igbo Cluster

Reconstructing the Igbo Cluster Author: Chinyere Ohiri - Aniche (Retired Professor of Language Education, University of Lagos, Nigeria). 1.0 General Information on the family 1.1 Geography, Population, Neighbour The Igbo language is spoken homogenously in five south-eastern states of Nigeria, namely: Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu and Imo. Igbo speakers are also found in parts of Rivers and Delta States in the south-south zone of Nigeria. Neighbours of the Igbo include the Igala, Tiv and Idoma to the north; the Anaang, Ibibio, Efik, to the south-east; the Urhobo, Isoko, Edo to the south-west and the Ijaw and Ogoni to the south-south delta areas. Wikipedia (2012) gives 27 million as the number of Igbo speakers. 1.2 (Pre) historic migrations and language contacts Many Igbos believe that they are of Hebrew origin, being one of the lost tribes of Israel. Afigbo (2000:12) however says that the Igbo are a negro people, originating in Africa, somewhere south of the latitude of Arselam and Khartoum. They later spread along the Niger-Benue confluence area with other groups. 1.3 History of scholarship Following her discovery that speech varieties hitherto referred to as Igbo were more diverse than had formally been realized, Williamson (1973) embarked upon a first reconstruction of these speech varieties into what she termed Proto-Lower Niger. In 1984 Prof. Kay Williamson invited her Ph.D student, Chinyere Ohiri-Aniche to join in the reconstruction of what came to be known as Comparative Igboid. Unfortunately, the Comparative Igboid work could not quite be finished and published before the demise of Prof. -

10 Nigeria: Ethno-Linguistic Competition in the Giant of Africa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SOAS Research Online 10-Simpson-c10 OUP172-Simpson (Typeset by spi publisher services, Delhi) 172 of 198 August 31, 2007 15:49 10 Nigeria: Ethno-linguistic Competition in the Giant of Africa Andrew Simpson and B. Akíntúndé Oyètádé 10.1 Introduction Nigeria is a country with an immense population of over 140 million, the largest in Africa, and several hundred languages and ethnic groups (over 400 in some estimates, 510 according to Ethnologue 2005), though with no single group being a majority, and the three largest ethnic groups together constituting only approximately half of the country’s total population. Having been formed as a united territory by British colonial forces in 1914, with artificially created borders arbitrarily including certain ethnic groups while dividing others with neighbouring states, Nigeria and its complex ethno- linguistic situation in many ways is a prime representation of the classic set of problems faced by many newly developing states in Africa when decisions of national language policy and planning have to be made, and the potential role of language in nation- building has to be determined. When independence came to Nigeria in 1960, it was agreed that English would be the country’s single official language, and there was little serious support for the possible attempted promotion of any of Nigeria’s indigenous languages into the role of national official language. This chapter considers the socio- political and historical background to the establishment of English as Nigeria’s official language, and the development of the country over the subsequent post-independence era, and asks the following question. -

The Status of the Languages Central Nigeria

THE STATUS OF THE LANGUAGES OF CENTRAL NIGERIA Paper presented at the Round Table on Language Death in Africa WOCAL, Leipzig, July 29th, 1997 and now published as; R.M. Blench 1998. The status of the languages of Central Nigeria. In: Brenzinger, M. ed. Endangered languages in Africa. 187-206. Köln: Köppe Verlag. Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone/Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 E-mail [email protected] http://homepage.ntlworld.com/roger_blench/RBOP.htm Cambridge, 14 September, 2003 1. Introduction 1.1 The Linguistic Geography of the Nigerian Middle Belt Nigeria is the most complex country in Africa, linguistically, and one of the most complex in the world. Crozier & Blench (1992) and the accompanying map has improved our knowledge of the geography of its languages but also reveals that much remains to be done. Confusion about status and nomenclature remains rife and the inaccessibility of many minority languages is an obstacle to research. The first attempts to place the languages of Nigeria into related groups took place in the nineteenth century. Of these, the most important was Koelle (1854), whose extensive wordlists permitted him to recognise the unity of the language groups today called Nupoid, Jukunoid and Edoid among others. Blench (1987) gives a brief history of the development of language classification in relation to Nigeria. Within Nigeria, the area of greatest diversity is the 'Middle Belt', the band of territory stretching across the country between the large language blocs of the semi-arid north and the humid forest along the coast.