British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 19 67-2009 for Full Functionality Please Open Using Acrobat 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tate Report 08-09

Tate Report 08–09 Report Tate Tate Report 08–09 It is the Itexceptional is the exceptional generosity generosity and and If you wouldIf you like would to find like toout find more out about more about PublishedPublished 2009 by 2009 by vision ofvision individuals, of individuals, corporations, corporations, how youhow can youbecome can becomeinvolved involved and help and help order of orderthe Tate of the Trustees Tate Trustees by Tate by Tate numerousnumerous private foundationsprivate foundations support supportTate, please Tate, contact please contactus at: us at: Publishing,Publishing, a division a divisionof Tate Enterprisesof Tate Enterprises and public-sectorand public-sector bodies that bodies has that has Ltd, Millbank,Ltd, Millbank, London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG helped Tatehelped to becomeTate to becomewhat it iswhat it is DevelopmentDevelopment Office Office www.tate.org.uk/publishingwww.tate.org.uk/publishing today andtoday enabled and enabled us to: us to: Tate Tate MillbankMillbank © Tate 2009© Tate 2009 Offer innovative,Offer innovative, landmark landmark exhibitions exhibitions London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG ISBN 978ISBN 1 85437 978 1916 85437 0 916 0 and Collectionand Collection displays displays Tel 020 7887Tel 020 4900 7887 4900 A catalogue record for this book is Fax 020 Fax7887 020 8738 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. DevelopDevelop imaginative imaginative education education and and available from the British Library. interpretationinterpretation programmes programmes AmericanAmerican Patrons Patronsof Tate of Tate Every effortEvery has effort been has made been to made locate to the locate the 520 West520 27 West Street 27 Unit Street 404 Unit 404 copyrightcopyright owners ownersof images of includedimages included in in StrengthenStrengthen and extend and theextend range the of range our of our New York,New NY York, 10001 NY 10001 this reportthis and report to meet and totheir meet requirements. -

CVAN Open Letter to the Secretary of State for Education

Press Release: Wednesday 12 May 2021 Leading UK contemporary visual arts institutions and art schools unite against proposed government cuts to arts education ● Directors of BALTIC, Hayward Gallery, MiMA, Serpentine, Tate, The Slade, Central St. Martin’s and Goldsmiths among over 300 signatories of open letter to Education Secretary Gavin Williamson opposing 50% cuts in subsidy support to arts subjects in higher education ● The letter is part of the nationwide #ArtIsEssential campaign to demonstrate the essential value of the visual arts This morning, the UK’s Contemporary Visual Arts Network (CVAN) have brought together leaders from across the visual arts sector including arts institutions, art schools, galleries and universities across the country, to issue an open letter to Gavin Williamson, the Secretary of State for Education asking him to revoke his proposed 50% cuts in subsidy support to arts subjects across higher education. Following the closure of the consultation on this proposed move on Thursday 6th May, the Government has until mid-June to come to a decision on the future of funding for the arts in higher education – and the sector aims to remind them not only of the critical value of the arts to the UK’s economy, but the essential role they play in the long term cultural infrastructure, creative ambition and wellbeing of the nation. Working in partnership with the UK’s Visual Arts Alliance (VAA) and London Art School Alliance (LASA) to galvanise the sector in their united response, the CVAN’s open letter emphasises that art is essential to the growth of the country. -

Bloomberg New Contemporaries 2010 26 November 2010 23 January 2011

Bloomberg 26 November 2010� New Contemporaries 23 January 2011 2010 Bloomberg New Contemporaries / 26 November 2010—23 January 2011 www.ica.org.uk/learning ICA possible that we may consider someone note that we’re really working with people Bloomberg involved with an institution in another in the show at every level, especially New Contemporaries country but for me I really feel that it is around the public programme, providing more distinguished if you retain that different platforms and situations for 2010 prominence of just having artists. We have encounter and discussion. Interview had ‘advice’ from someone suggesting that we have a collector and a dealer on MATT � It is very much the On Friday 29 October 2010, ICA the panel, or someone from the internationalism of art schools and their Learning Coordinator Vicky Carmichael sponsorship board, but then it becomes reputation. met with Director of New something else and introduces agendas I interviewed Hannah Rickards who Contemporaries, Rebecca Heald and that aren’t about the work. was in New Contemporaries in 2003, and ICA Curator, Matt Williams to discuss For me I love looking at art with other asked her if she felt she had developed a the upcoming exhibition. artists, I think you really get a different core group. I don’t think she had an perspective. Just look at the short texts in opportunity to for that to happen so much. this year’s catalogue. We held a social event last night at the VICKY � The ICA’s Learning team ICA and I felt it was really successful in encourage students to visit the ICA and MATT � If you did get a dealer or collector bringing people together. -

Royal Society of P Ortrait P Ainters 2 0 15

Royal Society of Portrait Painters 2015 2015 therp.co.uk RP Annual Exhibition 2015 Royal Society of Portrait Painters 17 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1Y 5BD Tel: 020 7930 6844 www.therp.co.uk Cover painting ‘Fabio’ by Brendan Kelly RP Designed and produced by Chris Drake Design Printed by Duncan Print Group Published by the Royal Society of Portrait Painters © 2015 Royal Society of Portrait Painters The Royal Society of Portrait Painters is a Registered Charity No. 327460 Royal Society of Portrait Painters Patron: Her Majesty The Queen Advisory Board Council Hanging Committee Anne Beckwith-Smith LVO Paul Brason Paul Brason Keith Benham Tom Coates Simon Davis Dame Elizabeth Esteve-Coll DBE Saied Dai Sam Dalby Lord Fellowes GCB GCVO QSO Sam Dalby Toby Wiggins Foreman Anupam Ganguli Sheldon Hutchinson Gallery Manager Damon de Laszlo Antony Williams John Deston The Hon. Sandra de Laszlo Selection Committee Philip Mould Exhibitions Officer Jane Bond Sir Christopher Ondaatje CBE OC Alistair Redgrift Sam Dalby Mark Stephens CBE Simon Davis Press and Publicity Daphne Todd OBE PPRP NEAC Hon. SWA Robin-Lee Hall Richard Fitzwilliams President Sheldon Hutchinson Liberty Rowley Robin-Lee Hall Melissa Scott-Miller Head of Commissions Toby Wiggins Vice President Annabel Elton Antony Williams Simon Davis ‘Conversations’ Prize Honorary Secretary Selection Committee Melissa Scott-Miller Anthony Eyton RA Honorary Treasurer Martin Gayford Jason Walker Philip Mould OBE Justin Urquhart Stewart Honorary Archivist Toby Wiggins 3 Deceased Honorary Members Past Presidents 2001 – 2002 Andrew Festing MBE 2002 – 2008 Susan Ryder NEAC Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema OM RA RWS 1891 – 1904 A. -

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007 Yesterday an extraordinary work of political-conceptual-appropriation-installation art went on view at Tate Britain. There’ll be those who say it isn’t art – and this time they may even have a point. It’s a punch in the face, and a bunch of questions. I’m not sure if I, or the Tate, or the artist, know entirely what the work is up to. But a chronology will help. June 2001: Brian Haw, a former merchant seaman and cabinet-maker, begins his pavement vigil in Parliament Square. Initially in opposition to sanctions on Iraq, the focus of his protest shifts to the “war on terror” and then the Iraq war. Its emphasis is on the killing of children. Over the next five years, his line of placards – with many additions from the public - becomes an installation 40 metres long. April 2005: Parliament passes the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act. Section 132 removes the right to unauthorised demonstration within one kilometre of Parliament Square. This embraces Whitehall, Westminster Abbey, the Home Office, New Scotland Yard and the London Eye (though Trafalgar Square is exempted). As it happens, the perimeter of the exclusion zone passes cleanly through both Buckingham Palace and Tate Britain. May 2006: The Metropolitan Police serve notice on Brian Haw to remove his display. The artist Mark Wallinger, best known for Ecce Homo (a statue of Jesus placed on the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square), is invited by Tate Britain to propose an exhibition for its long central gallery. -

Fine Arts 2008-2009

fine arts 2008-2009 SARA BARKER JOSEPH BEDFORD GABRIELLA BISETTO PENELOPE CAIN DRAGICA JANKETIC CARLIN LUKE CAULFIELD KATIE CUDDON GRAHAM DURWARD PIERRE GENDRON CELIA HEMPTON CATH KEAY REBECCA MADGIN AMANDA MARBURG RUTH MURRAY EDDIE PEAKE LIZ RIDEAL JAMES ROBERTSON DAVID SPERO AMIKAM TOREN fine arts 2008-2009 Sara Barker Joseph Bedford Gabriella Bisetto Penelope Cain Dragica Janketic Carlin Luke Caulfield Katie Cuddon Graham Durward Pierre Gendron Celia Hempton Cath Keay Rebecca Madgin Amanda Marburg Ruth Murray Eddie Peake Liz Rideal James Robertson David Spero Amikam Toren THE BRITISH SCHOOL AT ROME 1 The projects realised by GABRIELLA BISETTO, PENELOPE CAIN, AMANDA MARBURG have been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its Arts funding and advisory body. The Arts Council England Helen Chadwick Fellowship is organised and administered by The Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, University of Oxford and The British School at Rome with the support of Arts Council England and St Peter’s College, Oxford. Acknowledgements Edited by Jacopo Benci David Chandler, Photoworks, London Graphic design Silvia Stucky Prof. Mihai Barbulescu, Romanian Academy, Rome Photography courtesy of the artists and architects, except Martin Brody, American Academy in Rome Claudio Abate (pp. 16-17, 47), Serafino Amato (pp. 30-31), Joachim Blüher, Pia Gottschaller, German Academy Villa Luke Caulfield (pp. 13, 46), Fernando Maquieira (pp. 24-25), Massimo, Rome Jacopo Benci (cover image; pp. 6-11, 51, 64) Marianna Di Giansante, Francesca Monari, Timothy Mitchell, Translations Jacopo Benci Æmilia Hotel, Bologna Gianmatteo Nunziante, Nunziante Magrone Studio Legale Associato, Rome Published by THE BRITISH SCHOOL AT ROME Casa dell’Architettura, Ordine degli Architetti P.P.C. -

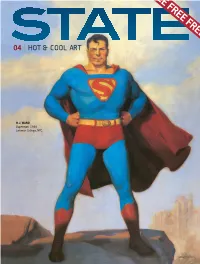

State 04 Layout 1

EE FREE FREE 04 | HOT & COOL ART H.J. WARD Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. Pulpit in Empty Chapel Oil on canvas Bed under Window Oil on canvas ‘How potent are these as ‘This new work is terrific in images of enclosed the emptiness of psychic secrecies!’ space in today's society, and MEL GOODING of the fragility of the sacred. Special works.’ DONALD KUSPIT stephen newton Represented in Northern England Represented in Southern England Abbey Walk Gallery Baker-Mamonova Galleries 8 Abbey Walk 45-53 Norman Road Grimsby St. Leonards-on-Sea www.newton-art.com Lincolnshire DN311NB East Sussex TN38 2QE >> IN THIS ISSUE COVER .%'/&)00+%00)6= IMAGE ,%713:)( H.J. Ward Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. ;IPSSOJSV[EVHXSWIIMRK]SYEXSYVRI[ 3 The first ever painting of Superman is the work of Hugh TVIQMWIW1EWSRW=EVH0SRHSR7; Joseph Ward (1909-1945) who died tragically young at 35 from cancer. He spent a lot of his time creating the sensational covers for pulp crime magazines, usually young 'YVVIRXP]WLS[MRK0IW*ERXSQIW[MXL women suggestively half-dressed, as well as early comic CONJURING THE ELEMENTS STREET STYLE REDUX [SVOF]%FSYHME%JIH^M,YKLIW0ISRGI book heroes like The Lone Ranger and Green Hornet. His main Public Art Triumphs Pin-point Paul Jones employer was Trojan Publications, but around 1940, Ward 08| 10 | 6ETLEIP%KFSHNIPSY&ERHSQE4EE.SI was commissioned to paint the first ever full length portrait of Superman to coincide with a radio show. He was paid ,EQEHSY1EMKE $100. The painting hung in the chief’s office at DC comics until mysteriously disappearing in 1957 (see editorial). -

The Gentleman's Library Sale

Montpelier Street, London I 12-13 February 2020 Montpelier Street, The Gentleman’s Library Sale Library The Gentleman’s The Gentleman’s Library Sale I Montpelier Street, London I 12-13 February 2020 25762 The Gentleman’s Library Sale Montpelier Street, London | Wednesday 12 - Thursday 13 February 2020 Wednesday 12 February, 10am Thursday 13 February, 10am Silver: Lots 1 to 287 Furniture, Carpets, Works of Art, Clocks: Lots 455 to 736 Wednesday 12 February, 2pm Books: Lots 288 to 297 Pictures: Lots 298 to 376 Collectors: 377 to 454 BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PRESS ENQUIRIES IMPORTANT INFORMATION Montpelier Street Senior Sale Coordinator [email protected] In February 2014 the United Knightsbridge Astrid Goettsch States Government announced London SW7 1HH +44 (0)20 7393 3975 CUSTOMER SERVICES the intention to ban the import www.bonhams.com [email protected] Monday to Friday of any ivory into the USA. Lots 8.30am – 6pm containing ivory are indicated by VIEWING Carpets +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 the symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 7 February, Helena Gumley-Mason Lot number in this catalogue. 9am to 4.30pm +44 (0) 20 8963 2845 SALE NUMBER REGISTRATION Sunday 9 February, [email protected] 25762 11am to 3pm IMPORTANT NOTICE Monday 10 February Furniture Please note that all customers, CATALOGUE 9am to 4.30pm Thomas Moore irrespective of any previous activity £15 Tuesday 11 February +44 (0) 20 8963 2816 with Bonhams, are required to 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] complete the Bidder Registration Please see page 2 for bidder Form in advance of the sale. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title No such thing as society : : art and the crisis of the European welfare state Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4mz626hs Author Lookofsky, Sarah Elsie Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO No Such Thing as Society: Art and the Crisis of the European Welfare State A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory and Criticism by Sarah Elsie Lookofsky Committee in charge: Professor Norman Bryson, Co-Chair Professor Lesley Stern, Co-Chair Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Grant Kester Professor Barbara Kruger 2009 Copyright Sarah Elsie Lookofsky, 2009 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Sarah Elsie Lookofsky is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii Dedication For my favorite boys: Daniel, David and Shannon iv Table of Contents Signature Page…….....................................................................................................iii Dedication.....................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents..........................................................................................................v Vita...............................................................................................................................vii -

Britain After Empire

Britain After Empire Constructing a Post-War Political-Cultural Project P. W. Preston Britain After Empire This page intentionally left blank Britain After Empire Constructing a Post-War Political-Cultural Project P. W. Preston Professor of Political Sociology, University of Birmingham, UK © P. W. Preston 2014 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2014 978-1-137-02382-7 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2014 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. -

Conference Abstracts Conference Abstracts

Conference Abstracts VictoriansVictorians Unbound:Unbound: ConnectionsConnections andand IntersectionsIntersections BishopBishop GrossetesteGrosseteste University,University, LincolnLincoln 2222ndnd –– 2424thth AugustAugust 20172017 0 Cover Image is The Prodigal Daughter, oil on canvas (1903) by John Maler Collier (1850 – 1934), a painting you can admire at The Collection and Usher Gallery, in Danes Terrace, Lincoln, LN2 1LP: www.thecollectionmuseum.com We are grateful to The Collection: Art and Archaeology in Lincolnshire (Usher Gallery, Lincoln) for giving us the permission to use this image. We thank Dawn Heywood, Collections Development Officer, for her generous help. 1 Contents BAVS 2017 Conference Organisers p. 3 BAVS 2017 Keynote Speakers p. 4 BAVS 2017 Opening Round Table Speakers p. 7 BAVS 2017 Delegates’ Abstracts Day One p. 9 BAVS 2017 Delegates’ Abstracts Day Two p. 27 BAVS 2017 Delegates’ Abstracts Day Three p. 70 BAVS 2017 President Panel p. 88 BAVS Annual Conference 2017 Online p. 89 BAVS Annual Conference 2017 WI-FI Access p. 89 BAVS 2017 Conference Helpers p. 90 Please note, Delegates’ email addresses are available together with their abstracts. 2 BAVS Annual Conference 2017 Victorians Unbound: Connections and Intersections Bishop Grosseteste University, Lincoln Organising Committee Dr Claudia Capancioni (chair), Bishop Grosseteste University Dr Alice Crossley (chair), University of Lincoln Dr Cassie Ulph, Bishop Grosseteste University Rosy Ward (administrator), Bishop Grosseteste University Organising Committee Assistants -

Damien Hirst Herausgegeben Von Ann Gallagher Mit Beiträgen Von Ann Gallagher Thomas Crow Michael Craig-Martin Nicholas Serota M

Damien Hirst Herausgegeben von Ann Gallagher Mit Beiträgen von Ann Gallagher Thomas Crow Michael Craig-Martin Nicholas Serota Michael Bracewell Brian Dillon Andrew Wilson PRESTEL München ˙ London ˙ New York TATE009_P0001EDhirstGerman.indd 1 09/02/2012 10:41 TATE009_P0001EDhirstGerman.indd 2 09/02/2012 10:41 TATE009_P0001EDhirstGerman.indd 3 09/02/2012 10:41 TATE009_P0001EDhirstGerman.indd 4 09/02/2012 10:41 Inhalt 6 Vorwort des Sponsors 7 Vorwort des Direktors 8 Dank 11 Einleitung Ann Gallagher 21 Hässliche Gefühle Brian Dillon 30 Tafeln I 38 Damien Hirst: Die frühen Jahre Michael Craig-Martin 40 Tafeln II 91 Nicholas Serota im Gespräch mit Damien Hirst, 14. Juli 2011 100 Tafeln III 180 Beautiful Inside My Head Forever Michael Bracewell 191 In der Glasmenagerie: Damien Hirst und Francis Bacon Thomas Crow 203 Der Glaubende Andrew Wilson 218 Chronologie 230 Literatur 232 Ausgestellte Werke 235 Bildnachweis 236 Register 244 Impressum TATE009_P0001EDhirstGerman.indd 5 09/02/2012 10:41 Vorwort des Sponsors Wenn die Welt später in diesem Jahr in London zu den Olympischen Spielen und den Paralympics zusammenkommt, werden wir daran erinnert werden, wie wichtig der Aufbau von Beziehun- gen mithilfe sportlicher und kultureller Veranstaltungen ist. Wie der Sport verbindet die bilden- de Kunst die Kulturen. Als universelle Sprache, die von allen gesprochen und verstanden wird, ist sie ein einzigartiges Medium, in dem sich die unterschiedlichen Stimmen Gehör verschaffen können. Die Arbeit der Qatar Museums Authority wird von der Überzeugung getragen, dass Kunst – auch kontroverse Kunst – Missverständnisse beseitigen und den Austausch zwischen den verschiedenen Nationen, Menschen und Traditionen anregen kann. Wir waren daher sehr erfreut, als Damien Hirst uns um die Unterstützung seiner Ausstellung in der Tate Modern bat.