Conference Abstracts Conference Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Willing Slaves: the Victorian Novel and the Afterlife of British Slavery

Willing Slaves: The Victorian Novel and the Afterlife of British Slavery Lucy Sheehan Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Lucy Sheehan All rights reserved ABSTRACT Willing Slaves: The Victorian Novel and the Afterlife of British Slavery Lucy Sheehan The commencement of the Victorian period in the 1830s coincided with the abolition of chattel slavery in the British colonies. Consequently, modern readers have tended to focus on how the Victorians identified themselves with slavery’s abolition and either denied their past involvement with slavery or imagined that slave past as insurmountably distant. “Willing Slaves: The Victorian Novel and the Afterlife of British Slavery” argues, however, that colonial slavery survived in the Victorian novel in a paradoxical form that I term “willing slavery.” A wide range of Victorian novelists grappled with memories of Britain’s slave past in ways difficult for modern readers to recognize because their fiction represented slaves as figures whose bondage might seem, counterintuitively, self-willed. Nineteenth-century Britons produced fictions of “willing slavery” to work through the contradictions inherent to nineteenth-century individualism. As a fictional subject imagined to take pleasure in her own subjection, the willing slave represented a paradoxical figure whose most willful act was to give up her individuality in order to maintain cherished emotional bonds. This figure should strike modern readers as a contradiction in terms, at odds with the violence and dehumanization of chattel slavery. But for many significant Victorian writers, willing slavery was a way of bypassing contradictions still familiar to us today: the Victorian individualist was meant to be atomistic yet sympathetic, possessive yet sheltered from market exchange, a monad most at home within the collective unit of the family. -

2017 Stevens Helen 1333274

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Paradise Closed Energy, inspiration and making art in Rome in the works of Harriet Hosmer, William Wetmore Story, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, Elizabeth Gaskell and Henry James, 1847-1903 Stevens, Helen Christine Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Paradise Closed: Energy, inspiration and making art in Rome in the works of Harriet Hosmer, William Wetmore Story, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, Elizabeth Gaskell and Henry James, 1847-1903 Helen Stevens 1 Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD King’s College London September, 2016 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... -

Christiana Herringham (8 December 1852–25 February 1929) Meaghan Clarke

Christiana Herringham (8 December 1852–25 February 1929) Meaghan Clarke Artist, writer, and suffragist, Christiana Herringham (Fig. 1) is primarily known as one of the founders of the National Art Collections Fund in 1903, along with the art writers Roger Fry, D. S. MacColl, and Claude Phillips, with the goal of acquiring works for the nation. Herringham had studied at the South Kensington School of Art and exhibited her early work at the Royal Academy. She married the physician Wilmot Herringham in 1880; Fig. 1: Christiana Herringham, c. 1906–11, photograph, Archives, Royal Holloway, University of London. 2 they had two sons. In 1899 she published the first English translation of Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte with notes on medieval artistic materials and methods. The latter derived largely from her own scientific experi- ments to replicate the techniques and recipes of early Renaissance tempera (egg yolk mixed with pigment). In 1901 she was one of a group of artists who exhibited ‘modern paintings’ in tempera at Leighton House, London, forming the Society of Painters in Tempera later that year. Society members exhibited again at the Carfax Gallery, London in 1905 and Herringham edited the Papers of the Society of Painters in Tempera, 1901–1907, which included her analysis of paintings in the collection of London’s National Gallery. TheBurlington Magazine was founded in 1903 and she served on its consultative committee. She published regularly with the journal over the next decade on a range of topics that encompassed the market for old masters, Albrecht Dürer, the proposed restoration of the basilica of San Marco, Venice, and Persian car- pets. -

Ästhetische Grundbegriffe (ÄGB) Bd

Termin 07.12.20 Von der »Bengal School« zur »Progressive Artists ʼ Group«: »Modernism« in Indien zwischen kolonialem Widerstand und staatlicher Unabhängigkeit Ankauf durch das Museum of Modern Art 1939 Ankauf durch das Museum durch Modern Art 1945 Die Entstehung von Museen für Moderne Kunst 1929 Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York 1947 Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris 1948 Museu de Arte Moderna (MAM), São Paulo; Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (MAMRio) 1951 Museum für moderne Kunst der Präfektur Kanagawa (Kanagawa Kenritsu Kindai Bijutsukan), Kamakura, Japan [1952 Aufbau der Sammlung moderner Kunst durch Rudolf Bornschein, Direktor der Saarlandmuseums; Grundstock der Modernen Galerie] 1954 National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), Neu-Dehli Museum of Modern Art, New York, im ersten "eigenen" Gebäude, 11 West 53rd Street, entworfen von Philipp L. Goodwin und Edward D. Stone, eröffnet Oktober 1939 Begriffsklärungen Modern / Moderne / Modernismus nach Cornelia Klinger, in: Ästhetische Grundbegriffe (ÄGB) Bd. 4, 2002 Cornelia Klinger: Modern/Moderne/Modernismus, in: Ästhetische Grundbegriffe. Historisches Wörterbuch in sieben Bänden, hg. v. Karlheinz Barck, Martin Fontius, Dieter Schlenstedt, Bd. 4, 2002/2010, S. 121-167. Begriffsklärungen Modern / Moderne / Modernismus nach Cornelia Klinger, in: Ästhetische Grundbegriffe (ÄGB) Bd. 4, 2002 "Modern" als Adjektiv Wortgeschichte reicht bis in die Antike zurück; abgeleitet von "modernus" im Lateinischen: relationales Zeitwort, das Heute von Gestern, Gegenwart von Vergangenheit, Neues -

Trollope Family Papers, 1825-1915

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3489n84w No online items Finding Aid for the Trollope Family Papers, 1825-1915 Processed by Esther Vécsey; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Trollope 712 1 Family Papers, 1825-1915 Finding Aid for the Trollope Family Papers, 1825-1915 Collection number: 712 UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Contact Information Manuscripts Division UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Telephone: 310/825-4988 (10:00 a.m. - 4:45 p.m., Pacific Time) Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ Processed by: Esther Vécsey, 28 April 1961 Encoded by: Caroline Cubé Text converted and initial container list EAD tagging by: Apex Data Services Online finding aid edited by: Josh Fiala, April 2002 © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Trollope Family Papers, Date (inclusive): 1825-1915 Collection number: 712 Creator: Trollope family Extent: 1 box (0.5 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Abstract: Frances Milton Trollope (1780-1863) was born in Stapleton, near Bristol, England. -

Ignorance and Marital Bliss: Women's Education in the English Novel, 1796-1895 Mary Tobin

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2006 Ignorance and Marital Bliss: Women's Education in the English Novel, 1796-1895 Mary Tobin Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Tobin, M. (2006). Ignorance and Marital Bliss: Women's Education in the English Novel, 1796-1895 (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1287 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ignorance and Marital Bliss: Women’s Education in the English Novel, 1796-1895 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Mary Ann Tobin November 16, 2006 Copyright © 2006 Mary Ann Tobin Preface The germ of this study lies in my master’s thesis, “Naive Altruist to Jaded Cosmopolitan: Class-Consciousness in David Copperfield, Bleak House, Great Expectations, and Our Mutual Friend,” with which I concluded my studies at Indiana State University. In it, I traced the evolution of Dickens’s ideal gentle Christian man, arguing that Dickens wanted his audience to reject a human valuation system based on birth and wealth and to set the standard for one’s social value upon the strength of one’s moral character. During my doctoral studies, I grew more interested in Dickens’s women characters and became intrigued by his contributions to what would become known as the Woman Question, and, more importantly, by what Dickens thought about women’s proper social functions and roles. -

The Gentleman's Library Sale

Montpelier Street, London I 12-13 February 2020 Montpelier Street, The Gentleman’s Library Sale Library The Gentleman’s The Gentleman’s Library Sale I Montpelier Street, London I 12-13 February 2020 25762 The Gentleman’s Library Sale Montpelier Street, London | Wednesday 12 - Thursday 13 February 2020 Wednesday 12 February, 10am Thursday 13 February, 10am Silver: Lots 1 to 287 Furniture, Carpets, Works of Art, Clocks: Lots 455 to 736 Wednesday 12 February, 2pm Books: Lots 288 to 297 Pictures: Lots 298 to 376 Collectors: 377 to 454 BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PRESS ENQUIRIES IMPORTANT INFORMATION Montpelier Street Senior Sale Coordinator [email protected] In February 2014 the United Knightsbridge Astrid Goettsch States Government announced London SW7 1HH +44 (0)20 7393 3975 CUSTOMER SERVICES the intention to ban the import www.bonhams.com [email protected] Monday to Friday of any ivory into the USA. Lots 8.30am – 6pm containing ivory are indicated by VIEWING Carpets +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 the symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 7 February, Helena Gumley-Mason Lot number in this catalogue. 9am to 4.30pm +44 (0) 20 8963 2845 SALE NUMBER REGISTRATION Sunday 9 February, [email protected] 25762 11am to 3pm IMPORTANT NOTICE Monday 10 February Furniture Please note that all customers, CATALOGUE 9am to 4.30pm Thomas Moore irrespective of any previous activity £15 Tuesday 11 February +44 (0) 20 8963 2816 with Bonhams, are required to 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] complete the Bidder Registration Please see page 2 for bidder Form in advance of the sale. -

The Greatest Living Critic”: Christiana Herringham and the Practise of Connoisseurship

The Greatest Living Critic”: Christiana Herringham and the practise of connoisseurship Meaghan Clarke Christina Herringham(1851–1929) was a founder and benefactor of the National Art- Collections Fund in 1903. 1 Her career as an artist and art writer is less well known. Herringham undertook early experimentation with tempera painting alongside her translation of Cennino Cennini’s (c.1370-c.1440) treatise on painting techniques. Herringham’s meticulous approach to understanding “medieval art methods” was a catalyst for the foundation of the Society of Painters in Tempera. Her writing for the art press, most notably for the Burlington Magazine where she was on the Consultative Committee, reveals her expertise on the technical aspects of connoisseurship. This paper traces the development of Herringham’s “scientific” method and highlights her pivotal role in a series of interconnecting networks. Knowledge and understanding of techniques and materials gave her a particular authority, just at the point that art history as a discipline was developing. Herringham’s interventions point to the need for a re-evaluation of male-centred narratives about the formation of art history. Key words: Connoisseurship; Christiana Herringham; (1851–1929); Cennino Cennini (DATES),; Sandro Botticelli (ca. 1445–1510); Burlington Magazine; Society of Painters in Tempera; Gender I have recently argued that women’s involvement in connoisseurship has been relatively unexplored, although figures such as Bernard Berenson and Fry have both been given considerable scholarly -

Names and Addresses of Living Bachelors and Masters of Arts, And

id 3/3? A3 ^^m •% HARVARD UNIVERSITY. A LIST OF THE NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF LIVING ALUMNI HAKVAKD COLLEGE. 1890, Prepared by the Secretary of the University from material furnished by the class secretaries, the Editor of the Quinquennial Catalogue, the Librarian of the Law School, and numerous individual graduates. (SKCOND YEAR.) Cambridge, Mass., March 15. 1890. V& ALUMNI OF HARVARD COLLEGE. \f *** Where no StateStat is named, the residence is in Mass. Class Secretaries are indicated by a 1817. Hon. George Bancroft, Washington, D. C. ISIS. Rev. F. A. Farley, 130 Pacific, Brooklyn, N. Y. 1819. George Salmon Bourne. Thomas L. Caldwell. George Henry Snelling, 42 Court, Boston. 18SO, Rev. William H. Furness, 1426 Pine, Philadelphia, Pa. 1831. Hon. Edward G. Loring, 1512 K, Washington, D. C. Rev. William Withington, 1331 11th, Washington, D. C. 18SS. Samuel Ward Chandler, 1511 Girard Ave., Philadelphia, Pa. 1823. George Peabody, Salem. William G. Prince, Dedham. 18S4. Rev. Artemas Bowers Muzzey, Cambridge. George Wheatland, Salem. 18S5. Francis O. Dorr, 21 Watkyn's Block, Troy, N. Y. Rev. F. H. Hedge, North Ave., Cambridge. 18S6. Julian Abbott, 87 Central, Lowell. Dr. Henry Dyer, 37 Fifth Ave., New York, N. Y. Rev. A. P. Peabody, Cambridge. Dr. W. L. Russell, Barre. 18S7. lyEpes S. Dixwell, 58 Garden, Cambridge. William P. Perkins, Wa}dand. George H. Whitman, Billerica. Rev. Horatio Wood, 124 Liberty, Lowell. 1828] 1838. Rev. Charles Babbidge, Pepperell. Arthur H. H. Bernard. Fredericksburg, Va. §3PDr. Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, 113 Boylston, Boston. Rev. Joseph W. Cross, West Boylston. Patrick Grant, 3D Court, Boston. Oliver Prescott, New Bedford. -

Women, Art, and Feeling at the Fin De Siècle

On tempera and temperament: women, art, and feeling at the fin de siècle Article (Published Version) Clarke, Meaghan (2016) On tempera and temperament: women, art, and feeling at the fin de siècle. 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century (23). ISSN 1755-1560 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/67309/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk On Tempera and Temperament: Women, Art, and Feeling at the Fin -

Trollopiana 100 Free Sample

THE JOURNAL OF THE Number 100 ~ Winter 2014/15 Bicentenary Edition EDITORIAL ~ 1 Contents Editorial Number 100 ~ Winter 2014-5 his 100th issue of Trollopiana marks the beginning of our FEATURES celebrations of Trollope’s birth 200 years ago on 24th April 1815 2 A History of the Trollope Society Tat 16 Keppel Street, London, the fourth surviving child of Thomas Michael Helm, Treasurer of the Trollope Society, gives an account of the Anthony Trollope and Frances Milton Trollope. history of the Society from its foundation by John Letts in 1988 to the As Trollope’s life has unfolded in these pages over the years present day. through members’ and scholars’ researches, it seems appropriate to begin with the first of a three-part series on the contemporary criticism 6 Not Only Ayala Dreams of an Angel of Light! If you have ever thought of becoming a theatre angel, now is your his novels created, together with a short history of the formation of our opportunity to support a production of Craig Baxter’s play Lady Anna at Society. Sea. During this year we hope to reach a much wider audience through the media and publications. Two new books will be published 7 What They Said About Trollope At The Time Dr Nigel Starck presents the first in a three-part review of contemporary by members: Dispossessed, the graphic novel based on John Caldigate by critical response to Trollope’s novels. He begins with Part One, the early Dr Simon Grennan and Professor David Skilton, and a new full version years of 1847-1858. -

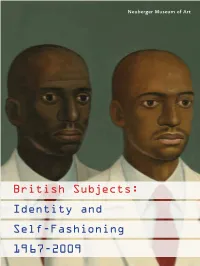

British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 19 67-2009 for Full Functionality Please Open Using Acrobat 8

Neuberger Museum of Art British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 19 67-2009 For full functionality please open using Acrobat 8. 4 Curator’s Foreword To view the complete caption for an illustration please roll your mouse over the figure or plate number. 5 Director’s Preface Louise Yelin 6 Visualizing British Subjects Mary Kelly 29 An Interview with Amelia Jones Susan Bright 37 The British Self: Photography and Self-Representation 49 List of Plates 80 Exhibition Checklist Copyright Neuberger Museum of Art 2009 Neuberger Museum of Art All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing from the publishers. Director’s Foreword Curator’s Preface British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 1967–2009 is the result of a novel collaboration British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 1967–2009 began several years ago as a study of across traditional disciplinary and institutional boundaries at Purchase College. The exhibition contemporary British autobiography. As a scholar of British and postcolonial literature, curator, Louise Yelin, is Interim Dean of the School of Humanities and Professor of Literature. I intended to explore the ways that the life writing of Britons—construing “Briton” and Her recent work addresses the ways that life writing and self-portraiture register subjective “British” very broadly—has registered changes in Britain since the Second World War. responses to changes in Britain since the Second World War. She brought extraordinary critical Influenced by recent work that expands the boundaries of what is considered under the insight and boundless energy to this project, and I thank her on behalf of a staff and audience rubric of autobiography and by interdisciplinary exchanges made possible by my institutional that have been enlightened and inspired.