UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studio International Magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’S Editorial Papers 1965-1975

Studio International magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’s editorial papers 1965-1975 Joanna Melvin 49015858 2013 Declaration of authorship I, Joanna Melvin certify that the worK presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this is indicated in the thesis. i Tales from Studio International Magazine: Peter Townsend’s editorial papers, 1965-1975 When Peter Townsend was appointed editor of Studio International in November 1965 it was the longest running British art magazine, founded 1893 as The Studio by Charles Holme with editor Gleeson White. Townsend’s predecessor, GS Whittet adopted the additional International in 1964, devised to stimulate advertising. The change facilitated Townsend’s reinvention of the radical policies of its founder as a magazine for artists with an international outlooK. His decision to appoint an International Advisory Committee as well as a London based Advisory Board show this commitment. Townsend’s editorial in January 1966 declares the magazine’s aim, ‘not to ape’ its ancestor, but ‘rediscover its liveliness.’ He emphasised magazine’s geographical position, poised between Europe and the US, susceptible to the influences of both and wholly committed to neither, it would be alert to what the artists themselves wanted. Townsend’s policy pioneered the magazine’s presentation of new experimental practices and art-for-the-page as well as the magazine as an alternative exhibition site and specially designed artist’s covers. The thesis gives centre stage to a British perspective on international and transatlantic dialogues from 1965-1975, presenting case studies to show the importance of the magazine’s influence achieved through Townsend’s policy of devolving responsibility to artists and Key assistant editors, Charles Harrison, John McEwen, and contributing editor Barbara Reise. -

A Guide to the Government for BIA Members

A guide to the Government for BIA members Correct as of 26 June 2020 This is a briefing for BIA members on the Government led by Boris Johnson and key ministerial appointments for our sector after the December 2019 General Election and February 2020 Cabinet reshuffle. Following the Conservative Party’s compelling victory, the Government now holds a majority of 80 seats in the House of Commons. The life sciences sector is high on the Government’s agenda and Boris Johnson has pledged to make the UK “the leading global hub for life sciences after Brexit”. With its strong majority, the Government has the power to enact the policies supportive of the sector in the Conservatives 2019 Manifesto. All in all, this indicates a positive outlook for life sciences during this Government’s tenure. Contents: Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector .......................................................................................... 2 Ministers and policy maker profiles................................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector* *Please note that this guide only covers ministers and responsibilities relevant to the life sciences and will be updated as further roles and responsibilities are announced. Department Position Holder Relevant responsibility Holder in -

Towards a Politics of (Relational) Aesthetics by Anthony Downey

This article was downloaded by: [Swets Content Distribution] On: 8 February 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 902276281] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Third Text Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713448411 Towards a Politics of (Relational) Aesthetics Anthony Downey Online Publication Date: 01 May 2007 To cite this Article Downey, Anthony(2007)'Towards a Politics of (Relational) Aesthetics',Third Text,21:3,267 — 275 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09528820701360534 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09528820701360534 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Third Text, Vol. 21, Issue 3, May, 2007, 267–275 Towards a Politics of (Relational) Aesthetics Anthony Downey 1 The subject of aesthetics The aesthetic criteria used to interpret art as a practice have changed and art criticism has been radically since the 1960s. -

Art and the Crisis of the European Welfare State Addresses Contemporary Art in the Context of Changing European Welfare States

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO No Such Thing as Society: Art and the Crisis of the European Welfare State A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory and Criticism by Sarah Elsie Lookofsky Committee in charge: Professor Norman Bryson, Co-Chair Professor Lesley Stern, Co-Chair Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Grant Kester Professor Barbara Kruger 2009 Copyright Sarah Elsie Lookofsky, 2009 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Sarah Elsie Lookofsky is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii Dedication For my favorite boys: Daniel, David and Shannon iv Table of Contents Signature Page…….....................................................................................................iii Dedication.....................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents..........................................................................................................v Vita...............................................................................................................................vii Abstract……………………………………………………………………………..viii Chapter 1: “And, You Know, There Is No Such Thing as Society.” ....................... 1 1.1 People vs. Population ............................................................................... 2 1.2 Institutional -

N.Paradoxa Online Issue 4, Aug 1997

n.paradoxa online, issue 4 August 1997 Editor: Katy Deepwell n.paradoxa online issue no.4 August 1997 ISSN: 1462-0426 1 Published in English as an online edition by KT press, www.ktpress.co.uk, as issue 4, n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal http://www.ktpress.co.uk/pdf/nparadoxaissue4.pdf August 1997, republished in this form: January 2010 ISSN: 1462-0426 All articles are copyright to the author All reproduction & distribution rights reserved to n.paradoxa and KT press. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying and recording, information storage or retrieval, without permission in writing from the editor of n.paradoxa. Views expressed in the online journal are those of the contributors and not necessarily those of the editor or publishers. Editor: [email protected] International Editorial Board: Hilary Robinson, Renee Baert, Janis Jefferies, Joanna Frueh, Hagiwara Hiroko, Olabisi Silva. www.ktpress.co.uk The following article was republished in Volume 1, n.paradoxa (print version) January 1998: N.Paradoxa Interview with Gisela Breitling, Berlin artist and art historian n.paradoxa online issue no.4 August 1997 ISSN: 1462-0426 2 List of Contents Editorial 4 VNS Matrix Bitch Mutant Manifesto 6 Katy Deepwell Documenta X : A Critique 9 Janis Jefferies Autobiographical Patterns 14 Ann Newdigate From Plants to Politics : The Particular History of A Saskatchewan Tapestry 22 Katy Deepwell Reading in Detail: Ndidi Dike Nnadiekwe (Nigeria) 27 N.Paradoxa Interview with Gisela Breitling, Berlin artist and art historian 35 Diary of an Ageing Art Slut 44 n.paradoxa online issue no.4 August 1997 ISSN: 1462-0426 3 Editorial, August 1997 The more things change, the more they stay the same or Plus ca change.. -

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007 Yesterday an extraordinary work of political-conceptual-appropriation-installation art went on view at Tate Britain. There’ll be those who say it isn’t art – and this time they may even have a point. It’s a punch in the face, and a bunch of questions. I’m not sure if I, or the Tate, or the artist, know entirely what the work is up to. But a chronology will help. June 2001: Brian Haw, a former merchant seaman and cabinet-maker, begins his pavement vigil in Parliament Square. Initially in opposition to sanctions on Iraq, the focus of his protest shifts to the “war on terror” and then the Iraq war. Its emphasis is on the killing of children. Over the next five years, his line of placards – with many additions from the public - becomes an installation 40 metres long. April 2005: Parliament passes the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act. Section 132 removes the right to unauthorised demonstration within one kilometre of Parliament Square. This embraces Whitehall, Westminster Abbey, the Home Office, New Scotland Yard and the London Eye (though Trafalgar Square is exempted). As it happens, the perimeter of the exclusion zone passes cleanly through both Buckingham Palace and Tate Britain. May 2006: The Metropolitan Police serve notice on Brian Haw to remove his display. The artist Mark Wallinger, best known for Ecce Homo (a statue of Jesus placed on the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square), is invited by Tate Britain to propose an exhibition for its long central gallery. -

PHILIPPE PARRENO Lives and Works in Paris, France Education

PHILIPPE PARRENO Lives and works in Paris, France Education 1983 – 1988 École des Beaux-Arts, Grenoble, France 1988 – 1989 Institut des Hautes Etudes en arts plastiques, Palais de Tokyo, Paris Selected Solo Exhibitions 2019 “Philippe Parreno: A Manifestation of Objects,” Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo “Echo,” Museum of Modern Art, New York “Displacing Realities,” LVMH Venice, Venice, Italy “Philippe Parreno,” Gladstone Gallery, New York 2018 “My Room is Another Fish Bowl,” Tensta Konsthall, Stockholm, Sweden “Philippe Parreno,” Pilar Corrias Gallery, London “Philippe Parreno,” Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin “Philippe Parreno: Two Automatons for One Duet (My Room Is Another Fish Bowl, 1996–2016, and With a Rhythmic Instinction to Be Able to Travel beyond Existing Forces of Life, 2014),” Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago 2017 “La Levadura y el Anfitrión,” Museo Jumex, Mexico City “Philippe Parreno: Synchronicity,” Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai, China “Philippe Parreno,” Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Serralves, Porto, Portugal 2016 “Philippe Parreno: Thenabouts,” Australian Center for the Moving Image, Melbourne, Australia “Anywhen,” Hyundai Commission 2016, Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London “My Room is Another Fish Bowl, The Brooklyn Museum, New York “IF THIS THEN ELSE,” Gladstone Gallery, New York 2015 “H{N)YPN(Y}OSIS,” Park Avenue Armory, New York “Hypothesis,” HangarBicocca, Milan, Italy 2014 “Quasi Objects,” Esther Schipper, Berlin “With a Rhythmic Instinction to be Able to Travel Beyond Existing Forces of Life,” Pilar Corrias, -

Changing the Narrative on Race and Racism: the Sewell Report and Culture Wars in the UK

Advances in Applied Sociology, 2021, 11, 384-403 https://www.scirp.org/journal/aasoci ISSN Online: 2165-4336 ISSN Print: 2165-4328 Changing the Narrative on Race and Racism: The Sewell Report and Culture Wars in the UK Andrew Pilkington University of Northampton, Northamptonshire, UK How to cite this paper: Pilkington, A. Abstract (2021). Changing the Narrative on Race and Racism: The Sewell Report and Culture The murder of George Floyd by police officers in the US in 2020 reignited the Wars in the UK. Advances in Applied Soci- Black Lives Matter movement and reverberated across the world. In the UK, ology, 11, 384-403. many young people demonstrated their determination to resist structural https://doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2021.118035 racism and some organisations subsequently acknowledged the need to take Received: July 30, 2021 action to promote race equality and reflect upon their historical role in colo- Accepted: August 21, 2021 nialism and slavery. At the same time, resistance to these challenges mounted, Published: August 24, 2021 with right-wing news media and the UK government initiating culture wars Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and to disparage attempts to combat structural racism and decolonise the curri- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. culum. This article argues that the campaign to discredit anti-racism culmi- This work is licensed under the Creative nated in 2021 in the production of the first major report on race for over 20 Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). years, a report chaired by Tony Sewell and commissioned by the government. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Drawing on critical discourse analysis, the author deconstructs this report. -

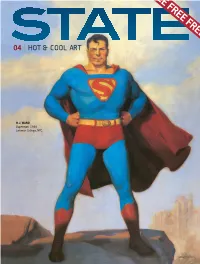

State 04 Layout 1

EE FREE FREE 04 | HOT & COOL ART H.J. WARD Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. Pulpit in Empty Chapel Oil on canvas Bed under Window Oil on canvas ‘How potent are these as ‘This new work is terrific in images of enclosed the emptiness of psychic secrecies!’ space in today's society, and MEL GOODING of the fragility of the sacred. Special works.’ DONALD KUSPIT stephen newton Represented in Northern England Represented in Southern England Abbey Walk Gallery Baker-Mamonova Galleries 8 Abbey Walk 45-53 Norman Road Grimsby St. Leonards-on-Sea www.newton-art.com Lincolnshire DN311NB East Sussex TN38 2QE >> IN THIS ISSUE COVER .%'/&)00+%00)6= IMAGE ,%713:)( H.J. Ward Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. ;IPSSOJSV[EVHXSWIIMRK]SYEXSYVRI[ 3 The first ever painting of Superman is the work of Hugh TVIQMWIW1EWSRW=EVH0SRHSR7; Joseph Ward (1909-1945) who died tragically young at 35 from cancer. He spent a lot of his time creating the sensational covers for pulp crime magazines, usually young 'YVVIRXP]WLS[MRK0IW*ERXSQIW[MXL women suggestively half-dressed, as well as early comic CONJURING THE ELEMENTS STREET STYLE REDUX [SVOF]%FSYHME%JIH^M,YKLIW0ISRGI book heroes like The Lone Ranger and Green Hornet. His main Public Art Triumphs Pin-point Paul Jones employer was Trojan Publications, but around 1940, Ward 08| 10 | 6ETLEIP%KFSHNIPSY&ERHSQE4EE.SI was commissioned to paint the first ever full length portrait of Superman to coincide with a radio show. He was paid ,EQEHSY1EMKE $100. The painting hung in the chief’s office at DC comics until mysteriously disappearing in 1957 (see editorial). -

Beyond Race & Multiculturalism

Beyond Race & Multiculturalism? Said Adrus Yunis Alam Chris Allen Claire Alexander Gargi Bhattacharyya Alastair Bonnett Jenny Bourne Nissa Finney David Gillborn Ian Law Alana Lentin Nasar Meer Shamim Miah Tariq Modood Karim Murji Lucinda Platt Said Adrus, ‘Fragile—Handle With Care’ 2008 (Mixed Media) Chris Vieler-Porter Robin Richardson Amir Saeed Gavan Titley D Tyrer Edited by AbdoolKarim Vakil Against Lazy Thinking as culturalist commonsense: Institutional racism is reduced to a phantom construct ‗where no one and Beyond Race and Multiculturalism? reproduces a everyone is guilty of racism‘; the Northern riots of 2001 series of critical comments and reflections contributed voided of social and historical depth and context; and to the MCB‘s ReDoc online Soundings platform. The relations of power are framed out of get-off-your-knees pieces were invited in response to the publication of repudiations of victimism and in appeals to embrace a Prospect Magazine‘s October 2010 feature dossier broader, universal, abstract and unmarked common ‗Rethinking Race‘. Compiled by Munira Mirza, the human identity. Mayor of London's advisor on arts and culture, the Prospect articles by Tony Sewell, Saran Singh, Sonia The responses collected here, issuing from and Dyer and Mirza herself span the areas of Education, informed by a range of disciplinary positions answer to Mental Health, the Arts, and social cohesion, no agenda other than to the call to critical engagement respectively. In conjunction, they make common front with the issues rather than the clichés. Mirza hopes on the argument that 'race is no longer the significant that the Prospect dossier will ‗embolden‘ the disadvantage it is often portrayed to be'; indeed, failure government to rethink the funding of anti-racist to accept the reality of our post-racial ‗human‘ times projects. -

West End Commission Final Report April 2013

West End Commission Final Report April 2013 WEST END COMMISSION Contents Foreword from the Chair 03 Summary of recommendations 04 About the Commission 09 About the West End 15 Governance and Leadership 26 Growth 35 • Transport 36 • Non-transport infrastructure 43 • Business 46 Place 51 • Crime, safety, night-time economy and licensing 52 • Environment 56 • Heritage and culture 59 • Marketing and promotion 61 People 63 • Housing 64 • Employment and skills 68 Annex 1: Primary data sources 71 Annex 2: Acknowledgements 71 Foreword from the Chair I have been a passionate promoter of cities as engines of national growth throughout my career. When I was invited to chair the independent West End Commission, I saw it as an opportunity to learn more myself about what makes successful places tick, but also to create a platform for serious debate to support the long-term success of a key national asset. This report is the culmination of many months of hard work by a number of people who have given up their time freely to listen, learn and discuss how the West End can respond to the challenges it faces, so that the area remains an attractive place to live and work and in addition, achieves world class excellence in corporate, visitor and enterprise activities. Fiscal restraint is a challenge for many places and not just the West End. So is the co-ordination of public services. What is different in the West End is not just the scale of the challenges, but also the need to tackle effectively the externalities which are associated with success. -

Artist Philippe Parreno Orchestrates Monumental Multi-Sensory Installation at Park Avenue Armory This June

Artist Philippe Parreno Orchestrates Monumental Multi-Sensory Installation At Park Avenue Armory this June Featuring new and reconfigured work as well as live performances by pianist Mikhail Rudy, exhibition marks the French artist’s first major New York show and largest project in the U.S. to date New York, NY—March 5, 2015—For his largest exhibition in the U.S. to date, Philippe Parreno constructs a multi- sensory journey within the monumental interior of Park Avenue Armory’s Wade Thompson Drill Hall—guiding and manipulating the audience’s experience through the spectral presence of sound and light. H {N)Y P N(Y} OSIS transforms the traditional exhibition experience into a scripted series of rotating events, incorporating new and re- mastered films and objects with live performances by pianist Mikhail Rudy and recorded sound that respond to the Armory’s expansive 55,000-square-foot space. Choreographed together, these works form an all encompassing and perpetually evolving artistic composition of operatic proportions. On view at the Armory from June 9 through August 2, 2015, H {N)Y P N(Y} OSIS (pronounced hypnosis) is commissioned by Park Avenue Armory and co-curated by Hans-Ulrich Obrist and Alex Poots, with consulting curator Tom Eccles. In addition to live music, the exhibition features recorded sound by Nicholas Becker and set design by Randall Peacock. “The Armory enables contemporary artists across genres to achieve their most ambitious visions, unconstrained by traditional settings. Philippe’s work in particular demands and thrives on this sort of creative freedom. His work radically redefines the exhibition ritual, transforming it from a series of individual works and experiences into a single unified event that interacts with and responds to our soaring drill hall,” said Rebecca Robertson, President and Executive Producer of Park Avenue Armory.