Changing the Narrative on Race and Racism: the Sewell Report and Culture Wars in the UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to the Government for BIA Members

A guide to the Government for BIA members Correct as of 26 June 2020 This is a briefing for BIA members on the Government led by Boris Johnson and key ministerial appointments for our sector after the December 2019 General Election and February 2020 Cabinet reshuffle. Following the Conservative Party’s compelling victory, the Government now holds a majority of 80 seats in the House of Commons. The life sciences sector is high on the Government’s agenda and Boris Johnson has pledged to make the UK “the leading global hub for life sciences after Brexit”. With its strong majority, the Government has the power to enact the policies supportive of the sector in the Conservatives 2019 Manifesto. All in all, this indicates a positive outlook for life sciences during this Government’s tenure. Contents: Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector .......................................................................................... 2 Ministers and policy maker profiles................................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector* *Please note that this guide only covers ministers and responsibilities relevant to the life sciences and will be updated as further roles and responsibilities are announced. Department Position Holder Relevant responsibility Holder in -

Art and the Crisis of the European Welfare State Addresses Contemporary Art in the Context of Changing European Welfare States

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO No Such Thing as Society: Art and the Crisis of the European Welfare State A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory and Criticism by Sarah Elsie Lookofsky Committee in charge: Professor Norman Bryson, Co-Chair Professor Lesley Stern, Co-Chair Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Grant Kester Professor Barbara Kruger 2009 Copyright Sarah Elsie Lookofsky, 2009 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Sarah Elsie Lookofsky is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii Dedication For my favorite boys: Daniel, David and Shannon iv Table of Contents Signature Page…….....................................................................................................iii Dedication.....................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents..........................................................................................................v Vita...............................................................................................................................vii Abstract……………………………………………………………………………..viii Chapter 1: “And, You Know, There Is No Such Thing as Society.” ....................... 1 1.1 People vs. Population ............................................................................... 2 1.2 Institutional -

Beyond Race & Multiculturalism

Beyond Race & Multiculturalism? Said Adrus Yunis Alam Chris Allen Claire Alexander Gargi Bhattacharyya Alastair Bonnett Jenny Bourne Nissa Finney David Gillborn Ian Law Alana Lentin Nasar Meer Shamim Miah Tariq Modood Karim Murji Lucinda Platt Said Adrus, ‘Fragile—Handle With Care’ 2008 (Mixed Media) Chris Vieler-Porter Robin Richardson Amir Saeed Gavan Titley D Tyrer Edited by AbdoolKarim Vakil Against Lazy Thinking as culturalist commonsense: Institutional racism is reduced to a phantom construct ‗where no one and Beyond Race and Multiculturalism? reproduces a everyone is guilty of racism‘; the Northern riots of 2001 series of critical comments and reflections contributed voided of social and historical depth and context; and to the MCB‘s ReDoc online Soundings platform. The relations of power are framed out of get-off-your-knees pieces were invited in response to the publication of repudiations of victimism and in appeals to embrace a Prospect Magazine‘s October 2010 feature dossier broader, universal, abstract and unmarked common ‗Rethinking Race‘. Compiled by Munira Mirza, the human identity. Mayor of London's advisor on arts and culture, the Prospect articles by Tony Sewell, Saran Singh, Sonia The responses collected here, issuing from and Dyer and Mirza herself span the areas of Education, informed by a range of disciplinary positions answer to Mental Health, the Arts, and social cohesion, no agenda other than to the call to critical engagement respectively. In conjunction, they make common front with the issues rather than the clichés. Mirza hopes on the argument that 'race is no longer the significant that the Prospect dossier will ‗embolden‘ the disadvantage it is often portrayed to be'; indeed, failure government to rethink the funding of anti-racist to accept the reality of our post-racial ‗human‘ times projects. -

West End Commission Final Report April 2013

West End Commission Final Report April 2013 WEST END COMMISSION Contents Foreword from the Chair 03 Summary of recommendations 04 About the Commission 09 About the West End 15 Governance and Leadership 26 Growth 35 • Transport 36 • Non-transport infrastructure 43 • Business 46 Place 51 • Crime, safety, night-time economy and licensing 52 • Environment 56 • Heritage and culture 59 • Marketing and promotion 61 People 63 • Housing 64 • Employment and skills 68 Annex 1: Primary data sources 71 Annex 2: Acknowledgements 71 Foreword from the Chair I have been a passionate promoter of cities as engines of national growth throughout my career. When I was invited to chair the independent West End Commission, I saw it as an opportunity to learn more myself about what makes successful places tick, but also to create a platform for serious debate to support the long-term success of a key national asset. This report is the culmination of many months of hard work by a number of people who have given up their time freely to listen, learn and discuss how the West End can respond to the challenges it faces, so that the area remains an attractive place to live and work and in addition, achieves world class excellence in corporate, visitor and enterprise activities. Fiscal restraint is a challenge for many places and not just the West End. So is the co-ordination of public services. What is different in the West End is not just the scale of the challenges, but also the need to tackle effectively the externalities which are associated with success. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title No such thing as society : : art and the crisis of the European welfare state Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4mz626hs Author Lookofsky, Sarah Elsie Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO No Such Thing as Society: Art and the Crisis of the European Welfare State A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory and Criticism by Sarah Elsie Lookofsky Committee in charge: Professor Norman Bryson, Co-Chair Professor Lesley Stern, Co-Chair Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Grant Kester Professor Barbara Kruger 2009 Copyright Sarah Elsie Lookofsky, 2009 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Sarah Elsie Lookofsky is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii Dedication For my favorite boys: Daniel, David and Shannon iv Table of Contents Signature Page…….....................................................................................................iii Dedication.....................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents..........................................................................................................v Vita...............................................................................................................................vii -

Hay-Festival-Programme-2016

HayCover16_Layout 1 13/04/2016 13:18 Page 1 HAY 16 DOC_Layout 1 21/04/2016 12:03 Page 3 01497 822 629 hayfestival.org Haymakers These are the writers and thinkers and Dyma’r awduron, y meddylwyr a’r diddanwyr a fydd entertainers who thrill us this year. These are yn ein gwefreiddio ni eleni. Y rhain yw’r merched a’r the women and men who inform the debate dynion sydd yn llywio’r drafodaeth am Ewrop, sydd about Europe, who are adventuring in new yn anturio mewn technolegau newydd ac sydd yn technologies, and who are broadening our ehangu ein meddyliau; y rhain yw’r ieithgwn sydd yn minds; and here are the lovers of language dathlu William Shakespeare, yr awdur mwyaf erioed – who cheer the celebrations of William a’r dramodydd a ddeallodd fwyaf am y galon ddynol. Shakespeare, the greatest writer who ever lived – Rydym yn dod at ein gilydd yn y dref hudolus hon, the playwright who understood most about the yn y mynyddoedd ysblennydd a hardd hyn, i ddathlu human heart. syniadau newydd a straeon ysbrydoledig; i siarad ac We are coming together in this magical town, in i gerdded, i rannu cacennau a chwrw, breuddwydion these spectacular and beautiful mountains, to a gobeithion; i gwrdd â hen ffrindiau ac i wneud celebrate new ideas and inspiring stories; to talk ffrindiau newydd. Croeso i’r Gelli Gandryll, croeso and walk, to share cakes and ale and dreams and i’r Wˆyl. Diolch i chi am ymuno â ni. hopes; to meet old friends and to make new ones. -

Arts Council England Annual Review 2009 HC

Annual review 2009 Great art for everyone – the Arts Council plan Building on artistic foundations Insight into arts audiences National Lottery etc Act 1993 (as amended by the National Lottery Act 1998) Presented pursuant to section c39, section 35 (5) of the National Lottery etc Act 1993 (as amended by the National Lottery Act 1998) for the year ending 31 March 2009, together with the Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General thereon. Arts Council England grant-in-aid and Lottery annual report and accounts 2008/09 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 16 July 2009 HC 854 London: The Stationery Office £26.60 Arts Council England annual review Arts Council England works to get great art to everyone by championing, developing and investing in artistic experiences that enrich people’s lives. As the national development agency for the arts, we support a range of artistic activities from theatre to music, literature to dance, photography to digital art, carnival to crafts. Great art inspires us, brings us together and teaches us about ourselves and the world around WELCOMEus. In short, it makes life better. Between 2008 and 2011 we’ll invest in excess of £1.6 billion of public money from the government and the National Lottery to create these experiences for as many people as possible across the country. © Crown Copyright 2009 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. -

The Inner Workings of British Political Parties the Interaction of Organisational Structures and Their Impact on Political Behaviours

REPORT The Inner Workings of British Political Parties The Interaction of Organisational Structures and their Impact on Political Behaviours Ben Westerman About the Author Ben Westerman is a Research Fellow at the Constitution Society specialising in the internal anthropology of political parties. He also works as an adviser on the implications of Brexit for a number of large organisations and policy makers across sectors. He has previously worked for the Labour Party, on the Remain campaign and in Parliament. He holds degrees from Bristol University and King’s College, London. The Inner Workings of British Political Parties: The Interaction of Organisational Structures and their Impact on Political Behaviours Introduction Since June 2016, British politics has entered isn’t working’,3 ‘Bollocks to Brexit’,4 or ‘New Labour into an unprecedented period of volatility and New Danger’5 to get a sense of the tribalism this fragmentation as the decision to leave the European system has engendered. Moreover, for almost Union has ushered in a fundamental realignment a century, this antiquated system has enforced of the UK’s major political groupings. With the the domination of the Conservative and Labour nation bracing itself for its fourth major electoral Parties. Ninety-five years since Ramsay MacDonald event in five years, it remains to be seen how and to became the first Labour Prime Minister, no other what degree this realignment will take place under party has successfully formed a government the highly specific conditions of a majoritarian (national governments notwithstanding), and every electoral system. The general election of winter government since Attlee’s 1945 administration has 2019 may well come to be seen as a definitive point been formed by either the Conservative or Labour in British political history. -

New Government and Prime Minister – August 2019

August 2019 New government and Prime Minister – August 2019 This briefing sets out an overview of the government appointments made by the new Prime Minister, Boris Johnson. Full profiles of the new ministerial team for health and social care are set out below, along with those for other key Cabinet appointments. This briefing also covers the election of the new Leader of the Liberal Democrats, Jo Swinson. Introduction In May 2019, Theresa May announced her intention to resign as Prime Minister and leader of the Conservative Party. Boris Johnson and Jeremy Hunt were the two leadership candidates chosen by Conservative MPs to be put to a ballot of their party membership. Boris Johnson received the largest number of nominations from Conservative MPs and 66% of the vote of party members. Theresa May officially resigned on Wednesday 24 July, with Boris Johnson becoming Prime Minister shortly afterwards. Boris Johnson made significant changes to the government, with less than half of Theresa May’s Cabinet remaining in post. Johnson did not maintain May’s approach of balancing those who voted leave and those who voted remain, instead promoting leading Brexit supporting figures to senior cabinet positions. A full list of Cabinet appointments is contained in Appendix 1. Matt Hancock remains in post as the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, with Caroline Dinenage and Baroness Blackwood also continuing in his ministerial team. They are joined by Chris Skidmore, Jo Churchill and Nadine Dorries. The Liberal Democrats also announced a new leader, Jo Swinson, on 22 July 2019. Swinson, previously the party’s deputy leader who held ministerial roles in the business and education departments under the Coalition government, takes over from former Business Secretary, Sir Vince Cable, who led the party for two years. -

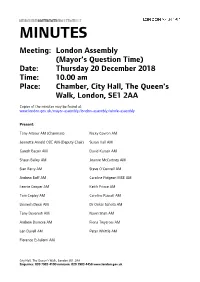

(Public Pack)Minutes Document for London Assembly (Mayor's

MINUTES Meeting: London Assembly (Mayor's Question Time) Date: Thursday 20 December 2018 Time: 10.00 am Place: Chamber, City Hall, The Queen's Walk, London, SE1 2AA Copies of the minutes may be found at: www.london.gov.uk/mayor-assembly/london-assembly/whole-assembly Present: Tony Arbour AM (Chairman) Nicky Gavron AM Jennette Arnold OBE AM (Deputy Chair) Susan Hall AM Gareth Bacon AM David Kurten AM Shaun Bailey AM Joanne McCartney AM Sian Berry AM Steve O'Connell AM Andrew Boff AM Caroline Pidgeon MBE AM Leonie Cooper AM Keith Prince AM Tom Copley AM Caroline Russell AM Unmesh Desai AM Dr Onkar Sahota AM Tony Devenish AM Navin Shah AM Andrew Dismore AM Fiona Twycross AM Len Duvall AM Peter Whittle AM Florence Eshalomi AM City Hall, The Queen’s Walk, London SE1 2AA Enquiries: 020 7983 4100 minicom: 020 7983 4458 www.london.gov.uk Greater London Authority London Assembly (Mayor's Question Time) Thursday 20 December 2018 1 Apologies for Absence and Chairman's Announcements (Item 1) 1.1 There were no apologies for absence. 1.2 The Chairman provided an update on recent Assembly working, including the Health Committee’s report ‘Supporting Londoner’s ambulance service’ and the #backtheplaque campaign. 1.3 During the course of the meeting, the Chairman welcomed to the public gallery pupils from South Park Primary School, Ilford. 2 Declarations of Interests (Item 2) 2.1 Resolved: That the list of offices held by Assembly Members, as set out in the table at Agenda Item 2, be noted as disclosable pecuniary interests. -

Annual Report on Special Advisers 2020

Annual Report on Special Advisers 2020 15 December 2020 Annual report on Special Advisers 2020 Present to Parliament pursuant to paragraphs 1 and 4 of section 16 of the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 © Crown copyright 2020 Produced by Cabinet Office You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Alternative versions of this report are available on request from [email protected] Annual Report on Special Advisers 2020 Contents Special Advisers 3 Number of Special Advisers 3 Cost of Special Advisers 3 Short Money 4 Special Adviser pay bands 4 List of Special Advisers 5 1 Annual Report on Special Advisers 2020 2 Annual Report on Special Advisers 2020 Special Advisers Special advisers are temporary civil servants appointed to add a political dimension to the advice and assistance available to Ministers. In doing so they reinforce the political impartiality of the permanent Civil Service by distinguishing the source of political advice and support. In accordance with section 16 of the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010, the Cabinet Office publishes an annual report containing the number and costs of special advisers. This information is presented below. The Cabinet Office also routinely publishes the names of all special advisers along with information on salaries. -

Dominic Cummings Much Was Written Around the Time of Mr Cummings

Dominic Cummings Much was written around the time of Mr Cummings’ resignation. Here is a sample: First: Robert Hutton Dominic Cummings’s 2020 vision Why didn’t Dom do data? The departure of Dominic Cummings from Boris Johnson’s administration will, we’re told, provide an opportunity for a “reset”. Certainly there’s likely to be a change of tone, if only because it would be hard to find anyone else who is as determined to have a fight with absolutely everyone. Or at least tell us that, or have their friends tell us that. But the government’s deepest problem will remain. Indeed, it predated both Johnson and Cummings’ arrival in Downing Street, though they are its parents. Brexit was marketed by Johnson and Cummings as a policy with no short-term economic harms It’s a problem exposed whenever we ask the prime minister’s office for an estimate of the economic impact of the government’s proposed Brexit model. Trust me on this: economic modelling matters to governments. Because even if you choose not to add the numbers up, they don’t go away. Margaret Thatcher would have known this. She’d have employed homely, personal-to-national metaphors involving pocketbooks. Alfred Sherman would have found the requisite bit of Dickens – ‘Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty-pound ought and six, result misery’. These are traditional Tory themes. Their underlying truths are really still there whenever a minister pops up talking about an “Australia-style” Brexit deal, for example. The problem is not that the government isn’t telling us the truth.