Britain After Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Companion to Nineteenth- Century Britain

A COMPANION TO NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITAIN Edited by Chris Williams A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Britain A COMPANION TO NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITAIN Edited by Chris Williams © 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 108, Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, Melbourne, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Chris Williams to be identified as the Author of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A companion to nineteenth-century Britain / edited by Chris Williams. p. cm. – (Blackwell companions to British history) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-631-22579-X (alk. paper) 1. Great Britain – History – 19th century – Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Great Britain – Civilization – 19th century – Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Williams, Chris, 1963– II. Title. III. Series. DA530.C76 2004 941.081 – dc22 2003021511 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 10 on 12 pt Galliard by SNP Best-set Typesetter Ltd., Hong Kong Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO BRITISH HISTORY Published in association with The Historical Association This series provides sophisticated and authoritative overviews of the scholarship that has shaped our current understanding of British history. -

JG Ballard's Reappraisal of Space

Keyes: J.G. Ballard’s Reappraisal of Space 48 From a ‘metallized Elysium’ to the ‘wave of the future’: J.G. Ballard’s Reappraisal of Space Jarrad Keyes Independent Scholar _____________________________________ Abstract: This essay argues that the ‘concrete and steel’ trilogy marks a pivotal moment in Ballard’s intellectual development. From an earlier interest in cities, typically London, Crash ([1973] 1995b), Concrete Island (1974] 1995a) and High-Rise ([1975] 2005) represent a threshold in Ballard’s spatial representations, outlining a critique of London while pointing the way to a suburban reorientation characteristic of his later works. While this process becomes fully realised in later representations of Shepperton in The Unlimited Dream Company ([1979] 1981) and the concept of the ‘virtual city’ (Ballard 2001a), the trilogy makes a number of important preliminary observations. Crash illustrates the roles automobility and containerisation play in spatial change. Meanwhile, the topography of Concrete Island delineates a sense of economic and spatial transformation, illustrating the obsolescence of the age of mechanical reproduction and the urban form of the metropolis. Thereafter, the development project in High-Rise is linked to deindustrialisation and gentrification, while its neurological metaphors are key markers of spatial transformation. The essay concludes by considering how Concrete Island represents a pivotal text, as its location demonstrates. Built in the 1960s, the Westway links the suburban location of Crash to the West with the Central London setting of High-Rise. In other words, Concrete Island moves athwart the new economy associated with Central London and the suburban setting of Shepperton, the ‘wave of the future’ as envisaged in Ballard’s works. -

The Brexit Vote: a Divided Nation, a Divided Continent

Sara Hobolt The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Hobolt, Sara (2016) The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23 (9). pp. 1259-1277. ISSN 1466-4429 DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785 © 2016 Routledge This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/67546/ Available in LSE Research Online: November 2016 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. The Brexit Vote: A Divided Nation, a Divided Continent Sara B. Hobolt London School of Economics and Political Science, UK ABSTRACT The outcome of the British referendum on EU membership sent shockwaves through Europe. While Britain is an outlier when it comes to the strength of Euroscepticism, the anti- immigration and anti-establishment sentiments that produced the referendum outcome are gaining strength across Europe. -

73 Custer, Wash., 9(1)

Custer: The Life of General George Armstrong the Last Decades of the Eighteenth Daily Life on the Nineteenth-Century Custer, by Jay Monaghan, review, Century, 66(1):36-37; rev. of Voyages American Frontier, by Mary Ellen 52(2):73 and Adventures of La Pérouse, 62(1):35 Jones, review, 91(1):48-49 Custer, Wash., 9(1):62 Cutter, Kirtland Kelsey, 86(4):169, 174-75 Daily News (Tacoma). See Tacoma Daily News Custer County (Idaho), 31(2):203-204, Cutting, George, 68(4):180-82 Daily Olympian (Wash. Terr.). See Olympia 47(3):80 Cutts, William, 64(1):15-17 Daily Olympian Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian A Cycle of the West, by John G. Neihardt, Daily Pacific Tribune (Olympia). See Olympia Manifesto, by Vine Deloria, Jr., essay review, 40(4):342 Daily Pacific Tribune review, 61(3):162-64 Cyrus Walker (tugboat), 5(1):28, 42(4):304- dairy industry, 49(2):77-81, 87(3):130, 133, Custer Lives! by James Patrick Dowd, review, 306, 312-13 135-36 74(2):93 Daisy, Tyrone J., 103(2):61-63 The Custer Semi-Centennial Ceremonies, Daisy, Wash., 22(3):181 1876-1926, by A. B. Ostrander et al., Dakota (ship), 64(1):8-9, 11 18(2):149 D Dakota Territory, 44(2):81, 56(3):114-24, Custer’s Gold: The United States Cavalry 60(3):145-53 Expedition of 1874, by Donald Jackson, D. B. Cooper: The Real McCoy, by Bernie Dakota Territory, 1861-1889: A Study of review, 57(4):191 Rhodes, with Russell P. -

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007 Yesterday an extraordinary work of political-conceptual-appropriation-installation art went on view at Tate Britain. There’ll be those who say it isn’t art – and this time they may even have a point. It’s a punch in the face, and a bunch of questions. I’m not sure if I, or the Tate, or the artist, know entirely what the work is up to. But a chronology will help. June 2001: Brian Haw, a former merchant seaman and cabinet-maker, begins his pavement vigil in Parliament Square. Initially in opposition to sanctions on Iraq, the focus of his protest shifts to the “war on terror” and then the Iraq war. Its emphasis is on the killing of children. Over the next five years, his line of placards – with many additions from the public - becomes an installation 40 metres long. April 2005: Parliament passes the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act. Section 132 removes the right to unauthorised demonstration within one kilometre of Parliament Square. This embraces Whitehall, Westminster Abbey, the Home Office, New Scotland Yard and the London Eye (though Trafalgar Square is exempted). As it happens, the perimeter of the exclusion zone passes cleanly through both Buckingham Palace and Tate Britain. May 2006: The Metropolitan Police serve notice on Brian Haw to remove his display. The artist Mark Wallinger, best known for Ecce Homo (a statue of Jesus placed on the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square), is invited by Tate Britain to propose an exhibition for its long central gallery. -

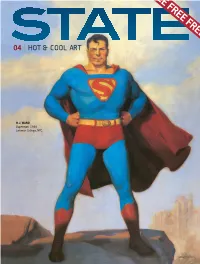

State 04 Layout 1

EE FREE FREE 04 | HOT & COOL ART H.J. WARD Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. Pulpit in Empty Chapel Oil on canvas Bed under Window Oil on canvas ‘How potent are these as ‘This new work is terrific in images of enclosed the emptiness of psychic secrecies!’ space in today's society, and MEL GOODING of the fragility of the sacred. Special works.’ DONALD KUSPIT stephen newton Represented in Northern England Represented in Southern England Abbey Walk Gallery Baker-Mamonova Galleries 8 Abbey Walk 45-53 Norman Road Grimsby St. Leonards-on-Sea www.newton-art.com Lincolnshire DN311NB East Sussex TN38 2QE >> IN THIS ISSUE COVER .%'/&)00+%00)6= IMAGE ,%713:)( H.J. Ward Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. ;IPSSOJSV[EVHXSWIIMRK]SYEXSYVRI[ 3 The first ever painting of Superman is the work of Hugh TVIQMWIW1EWSRW=EVH0SRHSR7; Joseph Ward (1909-1945) who died tragically young at 35 from cancer. He spent a lot of his time creating the sensational covers for pulp crime magazines, usually young 'YVVIRXP]WLS[MRK0IW*ERXSQIW[MXL women suggestively half-dressed, as well as early comic CONJURING THE ELEMENTS STREET STYLE REDUX [SVOF]%FSYHME%JIH^M,YKLIW0ISRGI book heroes like The Lone Ranger and Green Hornet. His main Public Art Triumphs Pin-point Paul Jones employer was Trojan Publications, but around 1940, Ward 08| 10 | 6ETLEIP%KFSHNIPSY&ERHSQE4EE.SI was commissioned to paint the first ever full length portrait of Superman to coincide with a radio show. He was paid ,EQEHSY1EMKE $100. The painting hung in the chief’s office at DC comics until mysteriously disappearing in 1957 (see editorial). -

Violence and Dystopia

Violence and Dystopia Violence and Dystopia: Mimesis and Sacrifice in Contemporary Western Dystopian Narratives By Daniel Cojocaru Violence and Dystopia: Mimesis and Sacrifice in Contemporary Western Dystopian Narratives By Daniel Cojocaru This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Daniel Cojocaru All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7613-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7613-1 For my daughter, and in loving memory of my father (1949 – 1991) TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction 1.1 Modern Dystopia ............................................................................. 1 1.2 René Girard’s Mimetic Theory ...................................................... 10 1.2.1 Imitative Desire ..................................................................... 10 1.2.2 Violence and the Sacred ........................................................ 16 1.2.3 Girard and the Bible ............................................................. -

Body and Space in J. G. Ballard's Concrete Island and High-Rise

Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Faculdade de Letras Pedro Henrique dos Santos Groppo Body and Space in J. G. Ballard’s Concrete Island and High-Rise Minas Gerais – Brasil Abril – 2009 Groppo 2 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Prof. Julio Jeha for the encouragement and support. He was always open and willing to make sense of my fragmentary and often chaotic ideas. Also, thanks to CNPq for the financial support. And big thanks to the J. G. Ballard online community, whose creativity and enthusiasm towards all things related to Ballard were captivating. Groppo 3 Abstract The fiction of J. G. Ballard is unusually concerned with spaces, both internal and exterior. Influenced by Surrealism and Freudian psychoanalysis, Ballard’s texts explore the thin divide between mind and body. Two of his novels of the 1970s, namely Concrete Island (1974) and High-Rise (1975) depict with detail his preoccupation with how the modern, urban world pushes man to the point where an escape to inner world is the solution to the tacit and oppressive forces of the external world. This escape is characterized by a suspension of conventional morality, with characters expressing atavistic tendencies, an effective return of the repressed. The present thesis poses a reading of these two novels, aided by analyses of some of Ballard’s short stories, with a focus on the relation between bodies and spaces and how they project and introject into one another. Such a reading is grounded on theories of the uncanny as described by Freud and highlights Ballard’s kinship to Gothic fiction. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title No such thing as society : : art and the crisis of the European welfare state Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4mz626hs Author Lookofsky, Sarah Elsie Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO No Such Thing as Society: Art and the Crisis of the European Welfare State A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory and Criticism by Sarah Elsie Lookofsky Committee in charge: Professor Norman Bryson, Co-Chair Professor Lesley Stern, Co-Chair Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Grant Kester Professor Barbara Kruger 2009 Copyright Sarah Elsie Lookofsky, 2009 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Sarah Elsie Lookofsky is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii Dedication For my favorite boys: Daniel, David and Shannon iv Table of Contents Signature Page…….....................................................................................................iii Dedication.....................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents..........................................................................................................v Vita...............................................................................................................................vii -

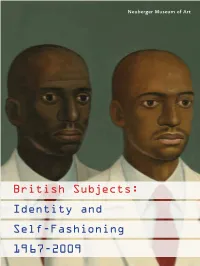

British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 19 67-2009 for Full Functionality Please Open Using Acrobat 8

Neuberger Museum of Art British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 19 67-2009 For full functionality please open using Acrobat 8. 4 Curator’s Foreword To view the complete caption for an illustration please roll your mouse over the figure or plate number. 5 Director’s Preface Louise Yelin 6 Visualizing British Subjects Mary Kelly 29 An Interview with Amelia Jones Susan Bright 37 The British Self: Photography and Self-Representation 49 List of Plates 80 Exhibition Checklist Copyright Neuberger Museum of Art 2009 Neuberger Museum of Art All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing from the publishers. Director’s Foreword Curator’s Preface British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 1967–2009 is the result of a novel collaboration British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 1967–2009 began several years ago as a study of across traditional disciplinary and institutional boundaries at Purchase College. The exhibition contemporary British autobiography. As a scholar of British and postcolonial literature, curator, Louise Yelin, is Interim Dean of the School of Humanities and Professor of Literature. I intended to explore the ways that the life writing of Britons—construing “Briton” and Her recent work addresses the ways that life writing and self-portraiture register subjective “British” very broadly—has registered changes in Britain since the Second World War. responses to changes in Britain since the Second World War. She brought extraordinary critical Influenced by recent work that expands the boundaries of what is considered under the insight and boundless energy to this project, and I thank her on behalf of a staff and audience rubric of autobiography and by interdisciplinary exchanges made possible by my institutional that have been enlightened and inspired. -

The 1974-75 UK Renegotiation of EEC Membership and Referendum

BRIEFING PAPER Number 7253, 13 July 2015 The 1974-75 UK Renegotiation of EEC By Vaughne Miller Membership and Referendum Inside: 1. Background 2. Labour referendum pledges 3. UK-EEC negotiations 4. The referendum 5. Further reading www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 7253, 13 July 2015 2 Contents Summary 4 1. Background 5 2. Labour referendum pledges 6 2.1 Labour’s 1974 manifestos 6 2.2 The Government informs the EEC Council 7 3. UK-EEC negotiations 11 3.1 Method and process 11 3.2 Results of the renegotiation 11 Parliamentary approval 18 Views in Europe 19 Public opinion 19 4. The referendum 20 4.1 White Paper on the EU referendum 20 4.2 The Referendum Bill 21 4.3 Referendum campaign and literature 21 5. Further reading 26 Cover page image copyright: EU flags by Gannon. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image cropped 3 The 1974-75 UK Renegotiation of EEC Membership and Referendum Number 7253, 13 July 2015 4 Summary The Labour general election manifestos in February and October 1974 promised a renegotiation of the UK’s terms of membership of the European Economic Community (EEC or Common Market), followed by a referendum on the UK’s continued membership. Having won the elections first without a majority and then with a narrow majority, in 1974 and 1975 Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson and his government negotiated concessions for the UK from other European governments. The main areas of UK concern were: - the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), - the UK contribution to the EEC Budget, - the goal of Economic and Monetary Union, - the harmonisation of VAT - Parliamentary sovereignty in pursuing regional, industrial and fiscal policies. -

4. Contemporary Art in London

저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게 l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다. l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer 미술경영학석사학위논문 Practice of Commissioning Contemporary Art by Tate and Artangel in London 런던의 테이트와 아트앤젤을 통한 현대미술 커미셔닝 활동에 대한 연구 2014 년 2 월 서울대학교 대학원 미술경영 학과 박 희 진 Abstract The practice of commissioning contemporary art has become much more diverse and complex than traditional patronage system. In the past, the major commissioners were the Church, State, and wealthy individuals. Today, a variety of entities act as commissioners, including art museums, private or public art organizations, foundations, corporations, commercial galleries, and private individuals. These groups have increasingly formed partnerships with each other, collaborating on raising funds for realizing a diverse range of new works. The term, commissioning, also includes this transformation of the nature of the commissioning models, encompassing the process of commissioning within the term. Among many commissioning models, this research focuses on examining the commissioning practiced by Tate and Artangel in London, in an aim to discover the reason behind London's reputation today as one of the major cities of contemporary art throughout the world.