4. Contemporary Art in London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tate Report 2010-11: List of Tate Archive Accessions

Tate Report 10–11 Tate Tate Report 10 –11 It is the exceptional generosity and vision If you would like to find out more about Published 2011 by of individuals, corporations and numerous how you can become involved and help order of the Tate Trustees by Tate private foundations and public-sector bodies support Tate, please contact us at: Publishing, a division of Tate Enterprises that has helped Tate to become what it is Ltd, Millbank, London SW1P 4RG today and enabled us to: Development Office www.tate.org.uk/publishing Tate Offer innovative, landmark exhibitions Millbank © Tate 2011 and Collection displays London SW1P 4RG ISBN 978-1-84976-044-7 Tel +44 (0)20 7887 4900 Develop imaginative learning programmes Fax +44 (0)20 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Strengthen and extend the range of our American Patrons of Tate Collection, and conserve and care for it Every effort has been made to locate the 520 West 27 Street Unit 404 copyright owners of images included in New York, NY 10001 Advance innovative scholarship and research this report and to meet their requirements. USA The publishers apologise for any Tel +1 212 643 2818 Ensure that our galleries are accessible and omissions, which they will be pleased Fax +1 212 643 1001 continue to meet the needs of our visitors. to rectify at the earliest opportunity. Or visit us at Produced, written and edited by www.tate.org.uk/support Helen Beeckmans, Oliver Bennett, Lee Cheshire, Ruth Findlay, Masina Frost, Tate Directors serving in 2010-11 Celeste -

Play and No Work? a 'Ludistory' of the Curatorial As Transitional Object at the Early

All Play and No Work? A ‘Ludistory’ of the Curatorial as Transitional Object at the Early ICA Ben Cranfield Tate Papers no.22 Using the idea of play to animate fragments from the archive of the Institute of Contemporary Arts, this paper draws upon notions of ‘ludistory’ and the ‘transitional object’ to argue that play is not just the opposite of adult work, but may instead be understood as a radical act of contemporary and contingent searching. It is impossible to examine changes in culture and its meaning in the post-war period without encountering the idea of play as an ideal mode and level of experience. From the publication in English of historian Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens in 1949 to the appearance of writer Richard Neville’s Play Power in 1970, play was used to signify an enduring and repressed part of human life that had the power to unite and oppose, nurture and destroy in equal measure.1 Play, as related by Huizinga to freedom, non- instrumentality and irrationality, resonated with the surrealist roots of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London and its attendant interest in the pre-conscious and unconscious.2 Although Huizinga and Neville did not believe play to be the exclusive preserve of childhood, a concern for child development and for the role of play in childhood grew in the post-war period. As historian Roy Kozlovsky has argued, the idea of play as an intrinsic and vital part of child development and as something that could be enhanced through policy making was enshrined within the 1959 Declaration of the -

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007 Yesterday an extraordinary work of political-conceptual-appropriation-installation art went on view at Tate Britain. There’ll be those who say it isn’t art – and this time they may even have a point. It’s a punch in the face, and a bunch of questions. I’m not sure if I, or the Tate, or the artist, know entirely what the work is up to. But a chronology will help. June 2001: Brian Haw, a former merchant seaman and cabinet-maker, begins his pavement vigil in Parliament Square. Initially in opposition to sanctions on Iraq, the focus of his protest shifts to the “war on terror” and then the Iraq war. Its emphasis is on the killing of children. Over the next five years, his line of placards – with many additions from the public - becomes an installation 40 metres long. April 2005: Parliament passes the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act. Section 132 removes the right to unauthorised demonstration within one kilometre of Parliament Square. This embraces Whitehall, Westminster Abbey, the Home Office, New Scotland Yard and the London Eye (though Trafalgar Square is exempted). As it happens, the perimeter of the exclusion zone passes cleanly through both Buckingham Palace and Tate Britain. May 2006: The Metropolitan Police serve notice on Brian Haw to remove his display. The artist Mark Wallinger, best known for Ecce Homo (a statue of Jesus placed on the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square), is invited by Tate Britain to propose an exhibition for its long central gallery. -

Yorkshire Sculpture Park EVA ROTHSCHILD Resource File

Yorkshire Sculpture Park EVA ROTHSCHILD Resource file Eva Rothschild (born 1972) is an Irish artist based in London. Rothschild was born in Dublin, Ireland. Her work references the art movements of the 1960s and 1970s, such as Minimalism. She has used materials such as Plexiglas, leather and paper in her sculptural pieces and she also makes wall-based works and videos. In 2003 she selected EASTinternational with Toby Webster. She is represented by Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London. Education 1997 – 1999 MA Fine Art, Goldsmith’s College, London 1990 – 1993 BA Hons Fine Art, University of Ulster, Belfast, Ireland Solo Exhibitions 2011 The Hepworth, Wakefield Public Art Fund, New York, USA (forthcoming) 2009 Duveen Galleries, Tate Britain, London Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zürich, Switzerland Francesca Kaufmann, Milan, Italy La Conservera: Centro de Arte Contemporaneo, Murcia 2008 Tate Britain, Millbank, London The Modern Institute, Glasgow, Scotland 2007 South London Gallery, London 303 Gallery, New York, USA 2006 Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich, Switzerland 2005 Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, Ireland Modern Art, London 2004 Kunsthalle, Zurich, Switzerland Artspace, Sydney, Australia 2003 Heavy Cloud, The Modern Institute, Glasgow, Scotland Sit-In, Galleria Francesca Kaufmann, Milan, Italy 2002 Modern Art, London Project Art Centre, Dublin, Ireland 2001 Eva Rothschild, Els Hannape Underground, Athens, Greece Peacegarden, The Showroom, London Peacegarden, Cornerhouse, Manchester, England Eva Rothschild, Francesca -

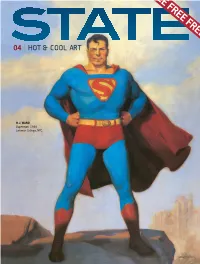

State 04 Layout 1

EE FREE FREE 04 | HOT & COOL ART H.J. WARD Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. Pulpit in Empty Chapel Oil on canvas Bed under Window Oil on canvas ‘How potent are these as ‘This new work is terrific in images of enclosed the emptiness of psychic secrecies!’ space in today's society, and MEL GOODING of the fragility of the sacred. Special works.’ DONALD KUSPIT stephen newton Represented in Northern England Represented in Southern England Abbey Walk Gallery Baker-Mamonova Galleries 8 Abbey Walk 45-53 Norman Road Grimsby St. Leonards-on-Sea www.newton-art.com Lincolnshire DN311NB East Sussex TN38 2QE >> IN THIS ISSUE COVER .%'/&)00+%00)6= IMAGE ,%713:)( H.J. Ward Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. ;IPSSOJSV[EVHXSWIIMRK]SYEXSYVRI[ 3 The first ever painting of Superman is the work of Hugh TVIQMWIW1EWSRW=EVH0SRHSR7; Joseph Ward (1909-1945) who died tragically young at 35 from cancer. He spent a lot of his time creating the sensational covers for pulp crime magazines, usually young 'YVVIRXP]WLS[MRK0IW*ERXSQIW[MXL women suggestively half-dressed, as well as early comic CONJURING THE ELEMENTS STREET STYLE REDUX [SVOF]%FSYHME%JIH^M,YKLIW0ISRGI book heroes like The Lone Ranger and Green Hornet. His main Public Art Triumphs Pin-point Paul Jones employer was Trojan Publications, but around 1940, Ward 08| 10 | 6ETLEIP%KFSHNIPSY&ERHSQE4EE.SI was commissioned to paint the first ever full length portrait of Superman to coincide with a radio show. He was paid ,EQEHSY1EMKE $100. The painting hung in the chief’s office at DC comics until mysteriously disappearing in 1957 (see editorial). -

On the Very Idea of a “Political” Work of Art*

The Journal of Political Philosophy: Volume 29, Number 1, 2021, pp. 25–45 On the Very Idea of a “Political” Work of Art* Diarmuid Costello Philosophy, University of Warwick I. “POLITICAL ART” AND/OR “POLITICAL ARTISTS” RT can be “political” in a variety of ways. Mobilizing these differences offers Acorrespondingly many ways for artists producing “political art” to understand themselves, and the activity in which they are engaged. To demonstrate this, I focus on a particular work of art (The Battle of Orgreave, 2001), by a particular contemporary artist (Jeremy Deller), seeking to locate it within this broader possibility space. The work consists in a re-enactment, as art, of a notoriously bloody confrontation that took place between police and picketing miners during the 1984–5 National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) strike. Deller has said of an earlier work, Acid Brass (1999), comprising the rearrangement for brass band of various acid house anthems from the 1980s: “It was a political work but not, I hope, in a hectoring way. To be called a ‘political artist’ is, for me, a kiss of death, as it suggests a fixed or dogmatic position like that of a politician.” Of The Battle of Orgreave. he remarked in the same interview: I went to a number of historical re-enactments, and they mostly seemed drained of the political and social narratives behind the original events … I wanted instead to work with re-enactors on a wholly political re-enactment of a battle … one that had taken place within living memory, that would be re-staged in the place it had happened, involving many of the people who had been there the first time round.1 *An early draft of this article was given at the Art and Politics symposium, held in conjunction with Jeremy Deller’s exhibition English Magic at Margate Contemporary (Nov. -

This Is a Pre-Proof Version. for Citation Consult Final Published Version in Hart, C. and Kelsey, D. (Eds.), Discourses of Diso

This is a pre-proof version. For citation consult final published version in Hart, C. and Kelsey, D. (eds.), Discourses of Disorder: Riots, Strikes and Protests in the Media. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp.133-153. Metaphor and the (1984-85) Miners’ Strike: A Multimodal Analysis Christopher Hart 0. Introduction Recent research in Cognitive Linguistics and Cognitive Linguistic Critical Discourse Studies (CL-CDS) has shown that metaphor plays a significant role in structuring our understanding of social identities, actions and events. This research also demonstrates that metaphorical modes of understanding are not restricted in their articulation to language but find expression too in visual and multimodal genres of communication. In this chapter, I show how one metaphorical framing – STRIKE IS WAR – featured in multimodal media representations of the 1984-85 British Miners’ Strike. I analyse this metaphorical framing from a critical semiotic standpoint to argue that the conceptualisations invoked by these framing efforts served to ‘otherise’ the miners while simultaneously legitimating the actions during the strike of the Government and the police. I begin, in Section 1, with a brief introduction to the British Miners’ Strike. In Section 2, I introduce in more detail cognitive metaphor theory and the notion of multimodal metaphor. In Section 3, I briefly introduce the data to be analysed. In Section 5, I show how the STRIKE IS WAR metaphor featured in the language of news reports as well as in two multimodal genres - press photographs and editorial cartoons - and consider the potential (de)legitimating effects of this framing. Finally, in Section 5, I offer some conclusions. -

LAWRENCE ALLOWAY Pedagogy, Practice, and the Recognition of Audience, 1948-1959

LAWRENCE ALLOWAY Pedagogy, Practice, and the Recognition of Audience, 1948-1959 In the annals of art history, and within canonical accounts of the Independent Group (IG), Lawrence Alloway's importance as a writer and art critic is generally attributed to two achievements: his role in identifying the emergence of pop art and his conceptualization of and advocacy for cultural pluralism under the banner of a "popular-art-fine-art continuum:' While the phrase "cultural continuum" first appeared in print in 1955 in an article by Alloway's close friend and collaborator the artist John McHale, Alloway himself had introduced it the year before during a lecture called "The Human Image" in one of the IG's sessions titled ''.Aesthetic Problems of Contemporary Art:' 1 Using Francis Bacon's synthesis of imagery from both fine art and pop art (by which Alloway meant popular culture) sources as evidence that a "fine art-popular art continuum now eXists;' Alloway continued to develop and refine his thinking about the nature and condition of this continuum in three subsequent teXts: "The Arts and the Mass Media" (1958), "The Long Front of Culture" (1959), and "Notes on Abstract Art and the Mass Media" (1960). In 1957, in a professionally early and strikingly confident account of his own aesthetic interests and motivations, Alloway highlighted two particular factors that led to the overlapping of his "consumption of popular art (industrialized, mass produced)" with his "consumption of fine art (unique, luXurious):' 3 First, for people of his generation who grew up interested in the visual arts, popular forms of mass media (newspapers, magazines, cinema, television) were part of everyday living rather than something eXceptional. -

Cover 3 1.Indd

Interface A journal for and about social movements VOL 3 ISSUE 1: REPRESSION & MOVEMENTS Interface: a journal for and about social movements Contents Volume 3 (1): i - iv (May 2011) Interface volume 3 issue 1 Repression and social movements Interface: a journal for and about social movements Volume 3 issue 1 (May 2011) ISSN 2009 – 2431 Table of contents (pp. i – iv) Editorial Cristina Flesher Fominaya and Lesley Wood, Repression and social movements (pp. 1 – 11) Articles: repression and social movements Peter Ullrich and Gina Rosa Wollinger, A surveillance studies perspective on protest policing: the case of video surveillance of demonstrations in Germany (P) (pp. 12- 38) Liz Thompson and Ben Rosenzweig, Public policy is class war pursued by other means: struggle and restructuring as international education economy (P) (pp. 39 - 80) Kristian Williams, The other side of the COIN: counter-insurgency and community policing (P) (pp. 81 - 117) Fernanda Maria Vieira and J. Flávio Ferreira, “Não somos chilenos, somos mapuches!”: as vozes do passado no presente da luta mapuche por seu território (P) (pp. 118 - 144) Roy Krøvel, From indios to indígenas: Guerrilla perspectives on indigenous peoples and repression in Mexico, Guatemala and Nicaragua (P) (pp. 145 – 171) i Interface: a journal for and about social movements Contents Volume 3 (1): i - iv (May 2011) Action / practice notes and event analysis Musab Younis, British tuition fee protest, November 9, 2010, London (event analysis, pp. 172 - 181) Dino Jimbi, Campanha “Não partam a minha casa” (action note, pp. 182 - 184) Mac Scott, G20 mobilizing in Toronto and community organizing: opportunities created and lessons learned (action note, pp. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title No such thing as society : : art and the crisis of the European welfare state Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4mz626hs Author Lookofsky, Sarah Elsie Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO No Such Thing as Society: Art and the Crisis of the European Welfare State A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory and Criticism by Sarah Elsie Lookofsky Committee in charge: Professor Norman Bryson, Co-Chair Professor Lesley Stern, Co-Chair Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Grant Kester Professor Barbara Kruger 2009 Copyright Sarah Elsie Lookofsky, 2009 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Sarah Elsie Lookofsky is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii Dedication For my favorite boys: Daniel, David and Shannon iv Table of Contents Signature Page…….....................................................................................................iii Dedication.....................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents..........................................................................................................v Vita...............................................................................................................................vii -

English, Media, and Information in the Post-Cox Era. PUB DATE 90 NOTE 9P.; In: CLE Working Papers 1; See FL 023 492

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 390 293 FL 023 494; AUTHOR Hart, Andrew TITLE English, Media, and Information in the Post-Cox Era. PUB DATE 90 NOTE 9p.; In: CLE Working Papers 1; see FL 023 492. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *English Instruction; Foreign Countries; Freedom of Information; Freedom of Speech; *Information Sources; Language Teachers; *Mass Media Role; *News Media; Press Opinion IDENTIFIERS *Cox Commission Report ABSTRACT This paper discusses the Cox Committee for English (England) proposals and suggests some theoretical and practical approaches to teaching about the exchange of information through a media education perspective, especially news reporting. Findings are based on research into approaches to media education presented in a series of broadcast radio programs for teachers in England. All newspapers have a common interest in protecting their position or editorial stance in the market; journalists learn quickly to adapt their work to the requirements of their newspaper. Technical features and conventions of specific media define their typical styles of presentation, although survival depends upon how effectively they can communicate with readers. The distortion of society's information base offers a threat that is recognized by Cox. It is suggested that media education by English teachers is a crucial element in providing strategic defenses against this distortion by enlarging pupils' critical understanding of how messages are generated, conveyed, and interpreted in different media. (Contains nine references.) (NAV) ******:.*i.AA:.A:.AAA:.AA:.A*)%**A**AAAAAAA:.AAA.****I',A;:i.A****1'.1 * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are tie best that can be made * from the original dLcument. -

Britain's Civil War Over Coal

Britain’s Civil War over Coal Britain’s Civil War over Coal: An Insider's View By David Feickert Edited by David Creedy and Duncan France Britain’s Civil War over Coal: An Insider's View Series: Work and Employment By David Feickert Edited by David Creedy and Duncan France This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Jing Feickert All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6768-0 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6768-9 Dedicated by David Feickert to Marina and Sonia and to the lads who so often took him away from them, his family, for ten years. In memory of Kevin Devaney, miner, lecturer, trade unionist, political activist—a good friend and wry observer of coal mining life. In memoriam David Feickert 1946-2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures............................................................................................ ix List of Tables .............................................................................................. x Foreword ................................................................................................... xi Preface ....................................................................................................