Play and No Work? a 'Ludistory' of the Curatorial As Transitional Object at the Early

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

King Mob Echo: from Gordon Riots to Situationists & Sex Pistols

KING MOB ECHO FROM 1780 GORDON RIOTS TO SITUATIONISTS SEX PISTOLS AND BEYOND BY TOM VAGUE INCOMPLETE WORKS OF KING MOB WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES DARK STAR LONDON ·- - � --- Printed by Polestar AUP Aberdeen Limited, Rareness Rd., Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen AB12 3LE § 11JJJDJJDILIEJMIIENf1r 1f(Q) KIINCGr JMI(Q)IB3 JECCIHI(Q) ENGLISH SECTION OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL IF([J)IF ffiIE V ([J) IL lUilII ([J) W §IFIEIEIIJ) IHIII§il([J) ffiY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY DEREK HARRIS AND MALCOLM HOPKINS Illustrations: 'The Riots in Moorfields' (cover), 'The London Riots', 'at Langdale's' by 'Phiz' Hablot K. Browne, Horwood's 1792-9 'Plan of London', 'The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle', 'Oliver Twist Manifesto' by Malcolm McLaren. Vagrants and historical shout outs: Sandra Belgrave, Stewart Home, Mark Jackson, Mark Saunders, Joe D. Stevens at NDTC, Boz & Phiz, J. Paul de Castro, Blue Bredren, Cockney Visionaries, Dempsey, Boss Goodman, Lord George Gordon, Chris Gray, Jonathon Green, Jefferson Hack, Christopher Hibbert, Hoppy, Ian Gilmour, Ish, Dzifa & Simone at The Grape, Barry Jennings, Joe Jones, Shaun Kerr, Layla, Lucas, Malcolm McLaren, John Mead, Simon Morrissey, Don Nicholson-Smith, Michel Prigent (pre-publicity), Charlie Radcliffe, Jamie Reid, George Robertson & Melinda Mash, Dragan Rad, George Rude, Naveen Saleh, Jon Savage, Valerie Solanas, Carolyn Starren & co at Kensington Library, Mark Stewart, Toko, Alex Trocchi, Fred & Judy Vermorel, Warren, Dr. Watson, Viv Westwood, Jack Wilkes, Dave & Stuart Wise Soundtrack: 'It's a London Thing' Scott Garcia, 'Going Mobile' The Who, 'Living for the City' Stevie Wonder, 'Boston Tea Party' Alex Harvey, 'Catholic Day' Adam and the Ants, 'Do the Strand' Roxy Music', 'Rev. -

LAWRENCE ALLOWAY Pedagogy, Practice, and the Recognition of Audience, 1948-1959

LAWRENCE ALLOWAY Pedagogy, Practice, and the Recognition of Audience, 1948-1959 In the annals of art history, and within canonical accounts of the Independent Group (IG), Lawrence Alloway's importance as a writer and art critic is generally attributed to two achievements: his role in identifying the emergence of pop art and his conceptualization of and advocacy for cultural pluralism under the banner of a "popular-art-fine-art continuum:' While the phrase "cultural continuum" first appeared in print in 1955 in an article by Alloway's close friend and collaborator the artist John McHale, Alloway himself had introduced it the year before during a lecture called "The Human Image" in one of the IG's sessions titled ''.Aesthetic Problems of Contemporary Art:' 1 Using Francis Bacon's synthesis of imagery from both fine art and pop art (by which Alloway meant popular culture) sources as evidence that a "fine art-popular art continuum now eXists;' Alloway continued to develop and refine his thinking about the nature and condition of this continuum in three subsequent teXts: "The Arts and the Mass Media" (1958), "The Long Front of Culture" (1959), and "Notes on Abstract Art and the Mass Media" (1960). In 1957, in a professionally early and strikingly confident account of his own aesthetic interests and motivations, Alloway highlighted two particular factors that led to the overlapping of his "consumption of popular art (industrialized, mass produced)" with his "consumption of fine art (unique, luXurious):' 3 First, for people of his generation who grew up interested in the visual arts, popular forms of mass media (newspapers, magazines, cinema, television) were part of everyday living rather than something eXceptional. -

Contem Porary Spring 07 Madcap's Last Laugh

Syd Prog:Nitin Prog 4/5/07 13:05 Page 1 barbican do something different Only Connect Tonight’s concert is part of the only connect series, the Barbican’s innovative series that c brings together the worlds of film, music and art by inviting exceptional musicians, composers, o artists and filmmakers to develop collaborations and present new work. n ‘Give a big hand to Only Connect, a series of events designed to cross borders and break Syd t down barriers, challenge idle preconception and encourage exceptional artists to experiment, e collaborate, provoke, stimulate and entertain.’ Time Out m For more details visit www.barbican.org.uk/onlyconnect p Barrett o The Barbican Centre is r There will be an interval in tonight’s concert. provided by the City of a Madcap’s London Corporation as No smoking in the auditorium. No cameras, part of its contribution to tape recorders or other recording the cultural life of London r equipment may be taken into the hall. and the nation. y Last Laugh s p do something different r i Find out n before they g Thu 10 May 7.30pm sell out! 0 7 E–updates Celebrating the th The easy way to hear about the arts www.barbican.org.uk/contemporary Barbican’s 25 birthday events and offers www.barbican.org.uk/25 Sign up at Free programme The Barbican is 25 in 2007 and to help celebrate we have arranged www.barbican.org.uk/e-updates a wide variety of special events and activities. This year’s Barbican contemporary Visit www.barbican.org.uk/25 music events are on sale now. -

Class Wargames Class Class Wargames Ludic Ludic Subversion Against Spectacular Capitalism

class wargames Class Wargames ludic Ludic subversion against spectacular capitalism subversion Why should radicals be interested in playing wargames? Surely the Left can have no interest in such militarist fantasies? Yet, Guy Debord – the leader of the Situationist International – placed such importance on his class invention of The Game of War that he described it as the most significant of against his accomplishments. wargames Intrigued by this claim, a multinational group of artists, activists and spectacular academics formed Class Wargames to investigate the political and strategic lessons that could be learnt from playing his ludic experiment. While the ideas of the Situationists continue to be highly influential in the development of subversive art and politics, relatively little attention has been paid to their strategic orientation. Determined to correct this deficiency, Class Wargames is committed to exploring how Debord used the capitalism metaphor of the Napoleonic battlefield to propagate a Situationist analysis of modern society. Inspired by his example, its members have also hacked other military simulations: H.G. Wells’ Little Wars; Chris Peers’ Reds versus Reds and Richard Borg’s Commands & Colors. Playing wargames is not a diversion from politics: it is the training ground of tomorrow’s cybernetic communist insurgents. Fusing together historical research on avant-garde artists, political revolutionaries and military theorists with narratives of five years of public performances, Class Wargames provides a strategic and tactical manual for overthrowing the economic, political and ideological hierarchies of early- 21st century neoliberal capitalism. The knowledge required to create a truly human civilisation is there to be discovered on the game board! richard ludic subversion against barbrook spectacular capitalism Minor Compositions An imprint of Autonomedia Front cover painting: Kimathi Donkor, Toussaint L’Ouverture at Bedourete (2004). -

FREE FESTIVAL 2014 28 August - 14 September

PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL PORTOBELLO FREE FESTIVAL 2014 28 August - 14 September POP UP CINEMA LONDON FILMS W10 5TY ROCK AND ROLL FILMS WESTBOURNE WORLD FILMS STUDIOS KID’S FILMS W10 5JJ VIDEO CAFE KPH ARTISTS W10 6HJ BLEK LE RAT www.portobellofilmfestival.com URBAN MYTHOLOGY/REALITY by Tom Vague Orwell Mansions, on the new become part of the multicultural recalls the Jewish boyfriend of his reputedly last seen at the Globe on Portobello Square W10 Notting Dale slum, along with wife’s sister going round the area Talbot Road and the Mangrove on development off Golborne Road, is English, Irish and Italian on his scooter and reporting back All Saints, and various other local named in allusion to George Orwell communities. to the West Indians on the addresses have claims to being living on Portobello Road (or A hundred years ago, at the whereabouts of the Teds. Hendrix crash pads. possibly the Orwellian style of the outbreak of the First World War the In punk rock mythology the Clash block?). He did indeed begin Electric Cinema was attacked in formed in Portobello market in does, however, have a naval origin. anti-German riots because the 1976. In other versions the pivotal The farm and its lane were named London and Provincial Electric meeting took place on Ladbroke in celebration of England’s defeat Theatres company was German- Grove, various other local streets of Spain in the 1739 battle of owned; not because the manager and the Lisson Grove dole office. Porto Belo (now in Panama), under was suspected of signalling to They did, however, frequent the management of Admiral Zeppelins from the roof. -

CHELSEA Space for IMMEDIATE RELEASE

PRESS RELEASE CHELSEA space FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE We are watching: OZ in London Private view: Tuesday 13 June, 6-8.30pm Exhibition continues: 14 June – 14 July 2017 OZ 22 (1969) cover by Martin Sharp, Richard Neville (Editor). ‘They [the conservative elite] were overly terrified, and that somehow in the fluorescent pages of our magazine in which we dealt with revolutionary politics, drugs, sexuality, racism, trying to be much more candid about these matters and very very defined, I think at last they felt if they could shut us up, if the could stop Oz, that they could somehow stop the rebellion.’ Richard Neville, ‘The Oz Trial, Innocents Defiled?’, BBC Radio 4, 17 May 1990 OZ magazine (London, 1967-1973), has come to be known as a publication that typified the Sixties, through its experimental approach to design, editorial and the lifestyle it depicted, often through its contributors whose lives became enmeshed in the publication as it gained popularity and notoriety. CHELSEA space 16 John Islip Street, London, SW1P 4JU www.chelseaspace.org PRESS RELEASE CHELSEA space FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The exhibition, We Are Watching: OZ in London, will explore the creative output of a range of the magazine’s contributors over the six years that it was based in London, where it provided a voice to young journalists, artists and designers. This international network included Richard Neville, Martin Sharp, Felix Dennis, Jim Anderson, Robert Whitaker, Philippe Mora and Germaine Greer. Several other individuals were also fundamental in the success of OZ, their hard work unaccredited at the time, including Marsha Rowe and Louise Ferrier. -

Hippie Hippie Shake by Richard Neville Pete Steedman [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Online Counterculture Studies Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 9 2018 [Review] Hippie Hippie Shake by Richard Neville Pete Steedman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ccs Recommended Citation Steedman, Pete, [Review] Hippie Hippie Shake by Richard Neville, Counterculture Studies, 1(1), 2018, 98-116. doi:10.14453/ ccs.v1.i1.9 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] [Review] Hippie Hippie Shake by Richard Neville Abstract The 60s, ew are constantly told, were a time of rebellion, a time of change, a time of hope, or just a self- indulgent game of the "me" generation, depending on point of view. The 60s ra e currently decried by a younger generation, jealous of the alleged freedoms and actions of the baby boomers who have supposedly left them nothing to inherit but the wind. Revisionist writers go to extraordinary lengths to debunk the mythology of the 60s, but in essence they mainly rail against the late 60s early 70s. In their attacks on the baby boomers they conveniently forget that the oldest of this demographic grouping was only 14 in 1960, and the vast majority of them were not even teenagers! Keywords hippies, counterculture, OZ Creative Commons License Creative ThiCommons works is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Attribution 4.0 License This journal article is available in Counterculture Studies: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ccs/vol1/iss1/9 Richard Neville, Hippie Hippie Shake: The Dreams, The Trips, The Trials, The Screw Ups, The Love Ins, The Sixties, Heinemann, London, 1995, 384p. -

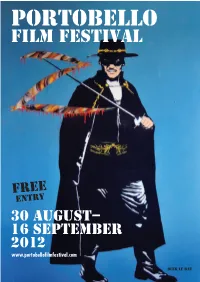

2012 Program

PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL FREE ENTRY 30 AUGUST– 16 SEPTEMBER 2012 www.portobellofilmfestival.com BLEK LE RAT Entry to all events if FREE and open to all over 18. ALTERNATIVE LONDON FILM FESTIVAL PORTOBELLO ALTERNATIVE PORTOBELLO POP UP CINEMA FILM FESTIVAL LONDON FILM INTERNATIONAL 3 ACKLAM ROAD, W10 5TY 30 Aug – 16 Sept 2012 FESTIVAL FILM FESTIVAL POP UP CINEMA WESTBOURNE Thu 30 Aug Welcome to the 17th Portobello Film Act Of Memory – 30 Aug 3 ACKLAM ROAD, W10 5TY STUDIOS GRAND OPENING Art at Festival. This year is non-stop new 30 August page 1 Portobello 242 ACKLAM ROAD, W10 5JJ CEREMONY London and UK films at the Pop Up Grand Opening Ceremony POP UP CINEMA Film Festival with The Spirit Of Portobello, docoBANKSY, 31 August page 9 2012 and a feast of international movies at and a new film from Ricky Grover International Shorts Introduction Westbourne Studios courtyard and Pop Up 1 September 9 6:30pm Cinema throughout the Festival, plus 7–19th at 31 August 2 The Muse Gallery – see page 18 for details. Westbourne Studios. Just For You London German Night What We Call Cookies up and coming directors inc Greg Hall & Wayne G Saunders (Natalie Hobbs) 2 mins It’s all very well watching films on the 2 September 10 Exploring various British stereotypes held by internet but nothing beats the live 1 September 2 International Feature Films Americans played out by motifs that are iconicly Are You Local? 3 September 11 American. Comedy. independent frontline film experience. West London film makers Turkish & Canadian Showcase Big Society (Nick Scott) 7 mins 2 September 3 An officer in the British army questions what it means We look forward to welcoming film 4 September 11 to fight for your country when he sees his hometown London Calling: From The Westway To British & USA State Of The Movie Art rife with antisocial behaviour. -

Punk · Film RARE PERIODICALS RARE

We specialize in RARE JOURNALS, PERIODICALS and MAGAZINES Please ask for our Catalogues and come to visit us at: rare PERIODIcAlS http://antiq.benjamins.com music · pop · beat · PUNk · fIlM RARE PERIODICALS Search from our Website for Unusual, Rare, Obscure - complete sets and special issues of journals, in the best possible condition. Avant Garde Art Documentation Concrete Art Fluxus Visual Poetry Small Press Publications Little Magazines Artist Periodicals De-Luxe editions CAT. Beat Periodicals 296 Underground and Counterculture and much more Catalogue No. 296 (2016) JOHN BENJAMINS ANTIQUARIAT Visiting address: Klaprozenweg 75G · 1033 NN Amsterdam · The Netherlands Postal address: P.O. BOX 36224 · 1020 ME Amsterdam · The Netherlands tel +31 20 630 4747 · fax +31 20 673 9773 · [email protected] JOHN BENJAMINS ANTIQUARIAT B.V. AMSTERDAM cat.296.cover.indd 1 05/10/2016 12:39:06 antiquarian PERIODIcAlS MUSIC · POP · BEAT · PUNK · FILM Cover illustrations: DOWN BEAT ROLLING STONE [#19111] page 13 [#18885] page 62 BOSTON ROCK FLIPSIDE [#18939] page 7 [#18941] page 18 MAXIMUM ROCKNROLL HEAVEN [#16254] page 36 [#18606] page 24 Conditions of sale see inside back-cover Catalogue No. 296 (2016) JOHN BENJAMINS ANTIQUARIAT B.V. AMSTERDAM 111111111111111 [#18466] DE L’AME POUR L’AME. The Patti Smith Fan Club Journal Numbers 5 and 6 (out of 8 published). October 1977 [With Related Ephemera]. - July 1978. [Richmond Center, WI]: (The Patti Smith Fan Club), (1978). Both first editions. 4to., 28x21,5 cm. side-stapled wraps. Photo-offset duplicated. Both fine, in original mailing envelopes (both opened a bit rough but otherwise good condition). EUR 1,200.00 Fanzine published in Wisconsin by Nanalee Berry with help from Patti’s mom Beverly. -

Cecil Beaton, Richard Hamilton and the Queer, Transatlantic Origins of Pop Art

Beaton and Hamilton, p. 1 JVC resubmission: Cecil Beaton, Richard Hamilton and the Queer, Transatlantic origins of Pop Art Abstract Significant aspects of American pop art are now understood as participating in the queer visual culture of New York in the 1960s. This article suggests something similar can be said of the British origins of pop art not only at the time of but also prior to the work of the Independent Group in post-war London. The interwar practices of collage of the celebrity photographer Cecil Beaton prefigured those of Richard Hamilton in that they displayed a distinctively British interpretation of male muscularity and female glamour in the United States. (Homo)eroticism in products of American popular culture such as advertising fascinated not simply Beaton but also a number of members of the Independent Group including Hamilton. The origins of pop art should, therefore, be situated in relation not only to American consumer culture but also to the ways in which that culture appeared, from certain British viewpoints, to be queerly intriguing. Keywords: Cecil Beaton, consumerism, homosexuality, Independent Group, Pop Art, Richard Hamilton, United States of America. Beaton and Hamilton, p. 2 Beaton and Hamilton, p. 3 Fig. 1. Richard Hamilton, Just What Is It that Makes Today’s Homes so Different, so Appealing?, 1956, collage, 26 x 25 cm, Kunsthalle Tübingen, Sammlung Zundel, © 2010 VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Beaton and Hamilton, p. 4 Fig. 2. Eduardo Paolozzi, Collage (Evadne in Green Dimension), 1952, collage, 30 x 26 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, CIRC 708-1971. Beaton and Hamilton, p. -

“Just What Was It That Made U.S. Art So Different, So Appealing?”

“JUST WHAT WAS IT THAT MADE U.S. ART SO DIFFERENT, SO APPEALING?”: CASE STUDIES OF THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE PAINTING IN LONDON, 1950-1964 by FRANK G. SPICER III Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Ellen G. Landau Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2009 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Frank G. Spicer III ______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy candidate for the ________________________________degree *. Dr. Ellen G. Landau (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) ________________________________________________Dr. Anne Helmreich Dr. Henry Adams ________________________________________________ Dr. Kurt Koenigsberger ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ December 18, 2008 (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Table of Contents List of Figures 2 Acknowledgements 7 Abstract 12 Introduction 14 Chapter I. Historiography of Secondary Literature 23 II. The London Milieu 49 III. The Early Period: 1946/1950-55 73 IV. The Middle Period: 1956-59: Part 1, The Tate 94 V. The Middle Period: 1956-59: Part 2 127 VI. The Later Period: 1960-1962 171 VII. The Later Period: 1963-64: Part 1 213 VIII. The Later Period: 1963-64: Part 2 250 Concluding Remarks 286 Figures 299 Bibliography 384 1 List of Figures Fig. 1 Richard Hamilton Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956) Fig. 2 Modern Art in the United States Catalogue Cover Fig. 3 The New American Painting Catalogue Cover Fig.