On the Povery of Student Life Considered in Its Economic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Play and No Work? a 'Ludistory' of the Curatorial As Transitional Object at the Early

All Play and No Work? A ‘Ludistory’ of the Curatorial as Transitional Object at the Early ICA Ben Cranfield Tate Papers no.22 Using the idea of play to animate fragments from the archive of the Institute of Contemporary Arts, this paper draws upon notions of ‘ludistory’ and the ‘transitional object’ to argue that play is not just the opposite of adult work, but may instead be understood as a radical act of contemporary and contingent searching. It is impossible to examine changes in culture and its meaning in the post-war period without encountering the idea of play as an ideal mode and level of experience. From the publication in English of historian Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens in 1949 to the appearance of writer Richard Neville’s Play Power in 1970, play was used to signify an enduring and repressed part of human life that had the power to unite and oppose, nurture and destroy in equal measure.1 Play, as related by Huizinga to freedom, non- instrumentality and irrationality, resonated with the surrealist roots of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London and its attendant interest in the pre-conscious and unconscious.2 Although Huizinga and Neville did not believe play to be the exclusive preserve of childhood, a concern for child development and for the role of play in childhood grew in the post-war period. As historian Roy Kozlovsky has argued, the idea of play as an intrinsic and vital part of child development and as something that could be enhanced through policy making was enshrined within the 1959 Declaration of the -

King Mob Echo: from Gordon Riots to Situationists & Sex Pistols

KING MOB ECHO FROM 1780 GORDON RIOTS TO SITUATIONISTS SEX PISTOLS AND BEYOND BY TOM VAGUE INCOMPLETE WORKS OF KING MOB WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES DARK STAR LONDON ·- - � --- Printed by Polestar AUP Aberdeen Limited, Rareness Rd., Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen AB12 3LE § 11JJJDJJDILIEJMIIENf1r 1f(Q) KIINCGr JMI(Q)IB3 JECCIHI(Q) ENGLISH SECTION OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL IF([J)IF ffiIE V ([J) IL lUilII ([J) W §IFIEIEIIJ) IHIII§il([J) ffiY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY DEREK HARRIS AND MALCOLM HOPKINS Illustrations: 'The Riots in Moorfields' (cover), 'The London Riots', 'at Langdale's' by 'Phiz' Hablot K. Browne, Horwood's 1792-9 'Plan of London', 'The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle', 'Oliver Twist Manifesto' by Malcolm McLaren. Vagrants and historical shout outs: Sandra Belgrave, Stewart Home, Mark Jackson, Mark Saunders, Joe D. Stevens at NDTC, Boz & Phiz, J. Paul de Castro, Blue Bredren, Cockney Visionaries, Dempsey, Boss Goodman, Lord George Gordon, Chris Gray, Jonathon Green, Jefferson Hack, Christopher Hibbert, Hoppy, Ian Gilmour, Ish, Dzifa & Simone at The Grape, Barry Jennings, Joe Jones, Shaun Kerr, Layla, Lucas, Malcolm McLaren, John Mead, Simon Morrissey, Don Nicholson-Smith, Michel Prigent (pre-publicity), Charlie Radcliffe, Jamie Reid, George Robertson & Melinda Mash, Dragan Rad, George Rude, Naveen Saleh, Jon Savage, Valerie Solanas, Carolyn Starren & co at Kensington Library, Mark Stewart, Toko, Alex Trocchi, Fred & Judy Vermorel, Warren, Dr. Watson, Viv Westwood, Jack Wilkes, Dave & Stuart Wise Soundtrack: 'It's a London Thing' Scott Garcia, 'Going Mobile' The Who, 'Living for the City' Stevie Wonder, 'Boston Tea Party' Alex Harvey, 'Catholic Day' Adam and the Ants, 'Do the Strand' Roxy Music', 'Rev. -

Contem Porary Spring 07 Madcap's Last Laugh

Syd Prog:Nitin Prog 4/5/07 13:05 Page 1 barbican do something different Only Connect Tonight’s concert is part of the only connect series, the Barbican’s innovative series that c brings together the worlds of film, music and art by inviting exceptional musicians, composers, o artists and filmmakers to develop collaborations and present new work. n ‘Give a big hand to Only Connect, a series of events designed to cross borders and break Syd t down barriers, challenge idle preconception and encourage exceptional artists to experiment, e collaborate, provoke, stimulate and entertain.’ Time Out m For more details visit www.barbican.org.uk/onlyconnect p Barrett o The Barbican Centre is r There will be an interval in tonight’s concert. provided by the City of a Madcap’s London Corporation as No smoking in the auditorium. No cameras, part of its contribution to tape recorders or other recording the cultural life of London r equipment may be taken into the hall. and the nation. y Last Laugh s p do something different r i Find out n before they g Thu 10 May 7.30pm sell out! 0 7 E–updates Celebrating the th The easy way to hear about the arts www.barbican.org.uk/contemporary Barbican’s 25 birthday events and offers www.barbican.org.uk/25 Sign up at Free programme The Barbican is 25 in 2007 and to help celebrate we have arranged www.barbican.org.uk/e-updates a wide variety of special events and activities. This year’s Barbican contemporary Visit www.barbican.org.uk/25 music events are on sale now. -

Class Wargames Class Class Wargames Ludic Ludic Subversion Against Spectacular Capitalism

class wargames Class Wargames ludic Ludic subversion against spectacular capitalism subversion Why should radicals be interested in playing wargames? Surely the Left can have no interest in such militarist fantasies? Yet, Guy Debord – the leader of the Situationist International – placed such importance on his class invention of The Game of War that he described it as the most significant of against his accomplishments. wargames Intrigued by this claim, a multinational group of artists, activists and spectacular academics formed Class Wargames to investigate the political and strategic lessons that could be learnt from playing his ludic experiment. While the ideas of the Situationists continue to be highly influential in the development of subversive art and politics, relatively little attention has been paid to their strategic orientation. Determined to correct this deficiency, Class Wargames is committed to exploring how Debord used the capitalism metaphor of the Napoleonic battlefield to propagate a Situationist analysis of modern society. Inspired by his example, its members have also hacked other military simulations: H.G. Wells’ Little Wars; Chris Peers’ Reds versus Reds and Richard Borg’s Commands & Colors. Playing wargames is not a diversion from politics: it is the training ground of tomorrow’s cybernetic communist insurgents. Fusing together historical research on avant-garde artists, political revolutionaries and military theorists with narratives of five years of public performances, Class Wargames provides a strategic and tactical manual for overthrowing the economic, political and ideological hierarchies of early- 21st century neoliberal capitalism. The knowledge required to create a truly human civilisation is there to be discovered on the game board! richard ludic subversion against barbrook spectacular capitalism Minor Compositions An imprint of Autonomedia Front cover painting: Kimathi Donkor, Toussaint L’Ouverture at Bedourete (2004). -

FREE FESTIVAL 2014 28 August - 14 September

PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL PORTOBELLO FREE FESTIVAL 2014 28 August - 14 September POP UP CINEMA LONDON FILMS W10 5TY ROCK AND ROLL FILMS WESTBOURNE WORLD FILMS STUDIOS KID’S FILMS W10 5JJ VIDEO CAFE KPH ARTISTS W10 6HJ BLEK LE RAT www.portobellofilmfestival.com URBAN MYTHOLOGY/REALITY by Tom Vague Orwell Mansions, on the new become part of the multicultural recalls the Jewish boyfriend of his reputedly last seen at the Globe on Portobello Square W10 Notting Dale slum, along with wife’s sister going round the area Talbot Road and the Mangrove on development off Golborne Road, is English, Irish and Italian on his scooter and reporting back All Saints, and various other local named in allusion to George Orwell communities. to the West Indians on the addresses have claims to being living on Portobello Road (or A hundred years ago, at the whereabouts of the Teds. Hendrix crash pads. possibly the Orwellian style of the outbreak of the First World War the In punk rock mythology the Clash block?). He did indeed begin Electric Cinema was attacked in formed in Portobello market in does, however, have a naval origin. anti-German riots because the 1976. In other versions the pivotal The farm and its lane were named London and Provincial Electric meeting took place on Ladbroke in celebration of England’s defeat Theatres company was German- Grove, various other local streets of Spain in the 1739 battle of owned; not because the manager and the Lisson Grove dole office. Porto Belo (now in Panama), under was suspected of signalling to They did, however, frequent the management of Admiral Zeppelins from the roof. -

2012 Program

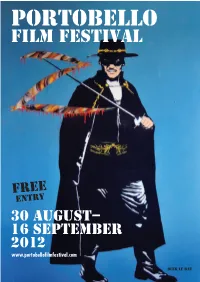

PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL FREE ENTRY 30 AUGUST– 16 SEPTEMBER 2012 www.portobellofilmfestival.com BLEK LE RAT Entry to all events if FREE and open to all over 18. ALTERNATIVE LONDON FILM FESTIVAL PORTOBELLO ALTERNATIVE PORTOBELLO POP UP CINEMA FILM FESTIVAL LONDON FILM INTERNATIONAL 3 ACKLAM ROAD, W10 5TY 30 Aug – 16 Sept 2012 FESTIVAL FILM FESTIVAL POP UP CINEMA WESTBOURNE Thu 30 Aug Welcome to the 17th Portobello Film Act Of Memory – 30 Aug 3 ACKLAM ROAD, W10 5TY STUDIOS GRAND OPENING Art at Festival. This year is non-stop new 30 August page 1 Portobello 242 ACKLAM ROAD, W10 5JJ CEREMONY London and UK films at the Pop Up Grand Opening Ceremony POP UP CINEMA Film Festival with The Spirit Of Portobello, docoBANKSY, 31 August page 9 2012 and a feast of international movies at and a new film from Ricky Grover International Shorts Introduction Westbourne Studios courtyard and Pop Up 1 September 9 6:30pm Cinema throughout the Festival, plus 7–19th at 31 August 2 The Muse Gallery – see page 18 for details. Westbourne Studios. Just For You London German Night What We Call Cookies up and coming directors inc Greg Hall & Wayne G Saunders (Natalie Hobbs) 2 mins It’s all very well watching films on the 2 September 10 Exploring various British stereotypes held by internet but nothing beats the live 1 September 2 International Feature Films Americans played out by motifs that are iconicly Are You Local? 3 September 11 American. Comedy. independent frontline film experience. West London film makers Turkish & Canadian Showcase Big Society (Nick Scott) 7 mins 2 September 3 An officer in the British army questions what it means We look forward to welcoming film 4 September 11 to fight for your country when he sees his hometown London Calling: From The Westway To British & USA State Of The Movie Art rife with antisocial behaviour. -

A Map for Countercultural Art in the 1960S: Transcultural Mobility and Art History

‘900 Transnazionale 3, 2 (2019) ISSN 2532-1994 doi: 10.13133/2532-1994.14790 Open access article licensed under CC-BY A map for countercultural art in the 1960s: Transcultural mobility and Art History Juliana F. Duque Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Belas Artes _________ Contact: Juliana F. Duque [email protected] ABSTRACT This article discusses the countercultural artistic expressions of the late 1960s as a transcultural phenomenon. These artistic expressions are the result of a network of ideas and trends, with an aesthetic born from the interchange among its participants. Despite its innovative character and the impact at the time, the relation of countercultural artistic practices within Art History is complex, not fitting into any precise artistic category or style. The 1960s, stage of several social and political revolutions around the world, saw the rise of manifestations such as Psychedelia. The decade was also noted for an increment on migrations, with more people being able to travel overseas, leading to the fading of geographical, social, and mental barriers. With more connections and means for traveling, more countercultural artists and young participants, from all social ranges, had the opportunity to go abroad and overseas. That increased the attendance at events, from rallies to psychedelic gatherings, influencing music and other countercultural artistic performances, including graphic design, painting, or light shows. Following the border-crossing tradition of the Beat Generation that got inputs from places such as Mexico, France, and even Russia years before, counterculture’s participants created a multicultural mosaic composed by music, poetry, visual arts, and graphic design. From the analysis of the mobility of prominent counterculture figures such as Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary or the Beatles, as well as of the artistic expressions, it is possible to map the countercultural artistic flows during the late 1960s between the United States, Britain, and beyond. -

In the Shadow of the Westway

LAUNCH Colville SPECIAL community history project issue 10 February 2015 under the flyover In the shadow of the Westway Following the ‘Orphans’ 1970 street photo blow-ups installation by Steve Mepsted in the Acklam farmers market bays 56-8, see back page, this issue focuses on life in the shadow of the Westway and before the flyover on Acklam Road and Tavistock Crescent; featuring Leslie Palmer’s Carnival office story on pages 3-5. Photos courtesy of Local Studies, North Kensington Community Archive, Charlie Phillips, and Old Notting Hill & North Kensington Facebook group. The 2015 Tabernacle exhibition/oral history project will be on Acklam/Tavistock under the flyover. The Westway Trust are proposing to rebuild and develop its properties under the Westway as the Portobello Village, starting with the Acklam Village site and the Portobello Green open tented area. The plans will be discussed at the next Colville Community Forum meeting at the Lighthouse to be announced. The architects and development manager are consulting at an early stage so all residents and Forum members will be able to offer ideas and input. The forthcoming 150 years of Portobello market celebrations include Book & Kitchen shop’s local literary timeline tour. Colville Community History Project colvillecom.com [email protected] getting it straight in notting hill gate Before and After the Westway/150 Years of Portobello Market In ‘Notting Hill in Bygone Days’, ‘there seems to be a By the 1870s, as the local MP William Bull recalled the natural break where the railway embankment crosses market was already established: 'Carnival time was on Portobello Road. -

Barrett Vol 1.Pdf

Introduction usician, psychedelic explorer, eccentric, cult icon – Roger “Syd” Barrett was many things to many people. Created in conjunction with the Barrett family and The Estate of Roger Barrett, who have provided unprece- dented access to family photographs, artworks, and mem- Mories, Barrett offers an intimate portrait of the Syd known only to his family and closest friends. Previously unseen photographs taken on seaside holidays and other family occasions show us a happy and loving young man, smiling energetically in images that map his early life, from childhood through his teenage years. Along with newly available photos from the album cover shoots for The Madcap Laughs and Barrett (taken by Storm Thorgerson and Mick Rock) they reveal the positive energy of a grinning Syd as he fools about in front of the camera. We are offered a rare glimpse of one who was immensely popular among friends and contemporaries. Also contained within these pages are recently unearthed images of Pink Floyd in which we see Syd practising handstands, making muscle-man poses, and having fun. The other members of Floyd lark about too – a fledgling young band enjoying itself with a sense of real camaraderie. The images transport one back in time to 166–67: the London Free School gigs, the launch of International Times at the Roundhouse, the UFO club, the band’s first European dates. There are photos of Syd and Floyd at numerous locations and events, giving a real sense of what it must have been like to be there as the infant light shows, experimentation, and collective spirit of the time emerged, grew, and flourished in the psychedelic hothouse that was the late 160s. -

1967: a Year in the Life of the Beatles

1967: A Year In The Life Of The Beatles History, Subjectivity, Music Linda Engebråten Masteroppgave ved Institutt for Musikkvitenskap UNIVERSITETET I OSLO November 2010 Acknowledgements First, I would like to express my gratitude towards my supervisor Stan Hawkins for all his knowledge, support, enthusiasm, and his constructive feedback for my project. We have had many rewarding discussions but we have also shared a few laughs about that special music and time I have been working on. I would also like to thank my fellow master students for both useful academically discussions as much as the more silly music jokes and casual conversations. Many thanks also to Joel F. Glazier and Nancy Cameron for helping me with my English. I thank John, Paul, George, and Ringo for all their great music and for perhaps being the main reason I begun having such a big interest and passion for music, and without whom I may not have pursued a career in a musical direction at all. Many thanks and all my loving to Joakim Krane Bech for all the support and for being so patient with me during the course of this process. Finally, I would like to thank my closest ones: my wonderful and supportive family who have never stopped believing in me. This thesis is dedicated to my grandparents. There are places I'll remember All my life though some have changed. Some forever not for better Some have gone and some remain. All these places have their moments With lovers and friends I still can recall. Some are dead and some are living, In my life I've loved them all. -

Christians and 'Race Relations' in the Sixties

Digging at Roots and Tugging at Branches: Christians and 'Race Relations' in the Sixties Submitted by Tank Green to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in September 2016 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. Page 1 Of 333 Page 2 Of 333 Abstract This thesis is a study of the ‘race relations’ work of Christians in the sixties in England, with specific reference to a Methodist church in Notting Hill, London. As such, it is also a study of English racisms: how they were fought against and how they were denied and facilitated. Additionally, the thesis pays attention to the interface of ‘religion’ and politics and the radical restatement of Christianity in the sixties. Despite a preponderance of sociological literature on 'race relations' and 'religion' in England, there has been a dearth of historical studies of either area in the post-war period. Therefore, this thesis is an important revision to the existing historiography in that it adds flesh to the bones of the story of post-war Christian involvement in the politics of 'race', and gives further texture and detail to the history of racism, 'race relations', and anti-racist struggles in England. -

A Critical Review Syd Barrett: a Very Irregular Head

University of Huddersfield Repository Chapman, Rob A Critical Review Syd Barrett: A Very Irregular Head Original Citation Chapman, Rob (2011) A Critical Review Syd Barrett: A Very Irregular Head. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/17530/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ UNIVERSITY OF HUDDERSFIELD PhD BY PUBLICATION ROB CHAPMAN A CRITICAL REVIEW SYD BARRETT : A VERY IRREGULAR HEAD ORIGINALLY SUBMITTED. DECEMBER 2011 RESUBMITTED WITH AMENDMENTS JULY 2012 CONTENTS. 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………..p3 2. METHODOLOGY………………………………………………………….p22 3. THE ART SCHOOL……………………………………………………….p54 4. PSYCHEDELIA……………………………………………………………p85 5. END NOTES……………………………………………………………….p114 6. BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………..p124 7. APPENDIX…………………………………………………………………p127 Copyright Statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and s/he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes.