A Map for Countercultural Art in the 1960S: Transcultural Mobility and Art History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Play and No Work? a 'Ludistory' of the Curatorial As Transitional Object at the Early

All Play and No Work? A ‘Ludistory’ of the Curatorial as Transitional Object at the Early ICA Ben Cranfield Tate Papers no.22 Using the idea of play to animate fragments from the archive of the Institute of Contemporary Arts, this paper draws upon notions of ‘ludistory’ and the ‘transitional object’ to argue that play is not just the opposite of adult work, but may instead be understood as a radical act of contemporary and contingent searching. It is impossible to examine changes in culture and its meaning in the post-war period without encountering the idea of play as an ideal mode and level of experience. From the publication in English of historian Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens in 1949 to the appearance of writer Richard Neville’s Play Power in 1970, play was used to signify an enduring and repressed part of human life that had the power to unite and oppose, nurture and destroy in equal measure.1 Play, as related by Huizinga to freedom, non- instrumentality and irrationality, resonated with the surrealist roots of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London and its attendant interest in the pre-conscious and unconscious.2 Although Huizinga and Neville did not believe play to be the exclusive preserve of childhood, a concern for child development and for the role of play in childhood grew in the post-war period. As historian Roy Kozlovsky has argued, the idea of play as an intrinsic and vital part of child development and as something that could be enhanced through policy making was enshrined within the 1959 Declaration of the -

New Books on Art & Culture

S11_cover_OUT.qxp:cat_s05_cover1 12/2/10 3:13 PM Page 1 Presorted | Bound Printed DISTRIBUTEDARTPUBLISHERS,INC Matter U.S. Postage PAID Madison, WI Permit No. 2223 DISTRIBUTEDARTPUBLISHERS . SPRING 2011 NEW BOOKS ON SPRING 2011 BOOKS ON ART AND CULTURE ART & CULTURE ISBN 978-1-935202-48-6 $3.50 DISTRIBUTED ART PUBLISHERS, INC. 155 SIXTH AVENUE 2ND FLOOR NEW YORK NY 10013 WWW.ARTBOOK.COM GENERAL INTEREST GeneralInterest 4 SPRING HIGHLIGHTS ArtHistory 64 Art 76 BookDesign 88 Photography 90 Writings&GroupExhibitions 102 Architecture&Design 110 Journals 118 MORE NEW BOOKS ON ART & CULTURE Special&LimitedEditions 124 Art 125 GroupExhibitions 147 Photography 157 Catalogue Editor Thomas Evans Architecture&Design 169 Art Direction Stacy Wakefield Forte Image Production Nicole Lee BacklistHighlights 175 Data Production Index 179 Alexa Forosty Copy Writing Sara Marcus Cameron Shaw Eleanor Strehl Printing Royle Printing Front cover image: Mark Morrisroe,“Fascination (Jonathan),” c. 1983. C-print, negative sandwich, 40.6 x 50.8 cm. F.C. Gundlach Foundation. © The Estate of Mark Morrisroe (Ringier Collection) at Fotomuseum Winterthur. From Mark Morrisroe, published by JRP|Ringier. See Page 6. Back cover image: Rodney Graham,“Weathervane (West),” 2007. From Rodney Graham: British Weathervanes, published by Christine Burgin/Donald Young. See page 87. Takashi Murakami,“Flower Matango” (2001–2006), in the Galerie des Glaces at Versailles. See Murakami Versailles, published by Editions Xavier Barral, p. 16. GENERAL INTEREST 4 | D.A.P. | T:800.338.2665 F:800.478.3128 GENERAL INTEREST Drawn from the collection of the Library of Congress, this beautifully produced book is a celebration of the history of the photographic album, from the turn of last century to the present day. -

King Mob Echo: from Gordon Riots to Situationists & Sex Pistols

KING MOB ECHO FROM 1780 GORDON RIOTS TO SITUATIONISTS SEX PISTOLS AND BEYOND BY TOM VAGUE INCOMPLETE WORKS OF KING MOB WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES DARK STAR LONDON ·- - � --- Printed by Polestar AUP Aberdeen Limited, Rareness Rd., Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen AB12 3LE § 11JJJDJJDILIEJMIIENf1r 1f(Q) KIINCGr JMI(Q)IB3 JECCIHI(Q) ENGLISH SECTION OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL IF([J)IF ffiIE V ([J) IL lUilII ([J) W §IFIEIEIIJ) IHIII§il([J) ffiY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY DEREK HARRIS AND MALCOLM HOPKINS Illustrations: 'The Riots in Moorfields' (cover), 'The London Riots', 'at Langdale's' by 'Phiz' Hablot K. Browne, Horwood's 1792-9 'Plan of London', 'The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle', 'Oliver Twist Manifesto' by Malcolm McLaren. Vagrants and historical shout outs: Sandra Belgrave, Stewart Home, Mark Jackson, Mark Saunders, Joe D. Stevens at NDTC, Boz & Phiz, J. Paul de Castro, Blue Bredren, Cockney Visionaries, Dempsey, Boss Goodman, Lord George Gordon, Chris Gray, Jonathon Green, Jefferson Hack, Christopher Hibbert, Hoppy, Ian Gilmour, Ish, Dzifa & Simone at The Grape, Barry Jennings, Joe Jones, Shaun Kerr, Layla, Lucas, Malcolm McLaren, John Mead, Simon Morrissey, Don Nicholson-Smith, Michel Prigent (pre-publicity), Charlie Radcliffe, Jamie Reid, George Robertson & Melinda Mash, Dragan Rad, George Rude, Naveen Saleh, Jon Savage, Valerie Solanas, Carolyn Starren & co at Kensington Library, Mark Stewart, Toko, Alex Trocchi, Fred & Judy Vermorel, Warren, Dr. Watson, Viv Westwood, Jack Wilkes, Dave & Stuart Wise Soundtrack: 'It's a London Thing' Scott Garcia, 'Going Mobile' The Who, 'Living for the City' Stevie Wonder, 'Boston Tea Party' Alex Harvey, 'Catholic Day' Adam and the Ants, 'Do the Strand' Roxy Music', 'Rev. -

Book Proposal 3

Rock and Roll has Tender Moments too... ! Photographs by Chalkie Davies 1973-1988 ! For as long as I can remember people have suggested that I write a book, citing both my exploits in Rock and Roll from 1973-1988 and my story telling abilities. After all, with my position as staff photographer on the NME and later The Face and Arena, I collected pop stars like others collected stamps, I was not happy until I had photographed everyone who interested me. However, given that the access I had to my friends and clients was often unlimited and 24/7 I did not feel it was fair to them that I should write it all down. I refused all offers. Then in 2010 I was approached by the National Museum of Wales, they wanted to put on a retrospective of my work, this gave me a special opportunity. In 1988 I gave up Rock and Roll, I no longer enjoyed the music and, quite simply, too many of my friends had died, I feared I might be next. So I put all of my negatives into storage at a friends Studio and decided that maybe 25 years later the images you see here might be of some cultural significance, that they might be seen as more than just pictures of Rock Stars, Pop Bands and Punks. That they even might be worthy of a Museum. So when the Museum approached me three years ago with the idea of a large six month Retrospective in 2015 I agreed, and thought of doing the usual thing and making a Catalogue. -

Contem Porary Spring 07 Madcap's Last Laugh

Syd Prog:Nitin Prog 4/5/07 13:05 Page 1 barbican do something different Only Connect Tonight’s concert is part of the only connect series, the Barbican’s innovative series that c brings together the worlds of film, music and art by inviting exceptional musicians, composers, o artists and filmmakers to develop collaborations and present new work. n ‘Give a big hand to Only Connect, a series of events designed to cross borders and break Syd t down barriers, challenge idle preconception and encourage exceptional artists to experiment, e collaborate, provoke, stimulate and entertain.’ Time Out m For more details visit www.barbican.org.uk/onlyconnect p Barrett o The Barbican Centre is r There will be an interval in tonight’s concert. provided by the City of a Madcap’s London Corporation as No smoking in the auditorium. No cameras, part of its contribution to tape recorders or other recording the cultural life of London r equipment may be taken into the hall. and the nation. y Last Laugh s p do something different r i Find out n before they g Thu 10 May 7.30pm sell out! 0 7 E–updates Celebrating the th The easy way to hear about the arts www.barbican.org.uk/contemporary Barbican’s 25 birthday events and offers www.barbican.org.uk/25 Sign up at Free programme The Barbican is 25 in 2007 and to help celebrate we have arranged www.barbican.org.uk/e-updates a wide variety of special events and activities. This year’s Barbican contemporary Visit www.barbican.org.uk/25 music events are on sale now. -

Postmodernism

Black POSTMODERNISM STYLE AND SUBVERSION, 1970–1990 TJ254-3-2011 IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm 175L 130 Stora Enso M/A Magenta(V) 130 Stora Enso M/A 175L IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm TJ254-3-2011 1 Black Black POSTMODERNISM STYLE AND SUBVERSION, 1970–1990 TJ254-3-2011 IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm 175L 130 Stora Enso M/A Magenta(V) 130 Stora Enso M/A 175L IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm TJ254-3-2011 Edited by Glenn Adamson and Jane Pavitt V&A Publishing TJ254-3-2011 IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm 175L 130 Stora Enso M/A Magenta(V) 130 Stora Enso M/A 175L IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm TJ254-3-2011 2 3 Black Black Exhibition supporters Published to accompany the exhibition Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1970 –1990 Founded in 1976, the Friends of the V&A encourage, foster, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London assist and promote the charitable work and activities of 24 September 2011 – 15 January 2012 the Victoria and Albert Museum. Our constantly growing membership now numbers 27,000, and we are delighted that the success of the Friends has enabled us to support First published by V&A Publishing, 2011 Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1970–1990. Victoria and Albert Museum South Kensington Lady Vaizey of Greenwich CBE London SW7 2RL Chairman of the Friends of the V&A www.vandabooks.com Distributed in North America by Harry N. Abrams Inc., New York The exhibition is also supported by © The Board of Trustees of the Victoria and Albert Museum, 2011 The moral right of the authors has been asserted. -

And Acquaintances Recall Their Dealings with The

REASONS TO BE CHEERFUL: THE LIFE AND WORK OF BARNEY BUBBLES by paul gorman Book reviewed by Andy Martin 2 4 1 In 1974, forsaking the wisdom with finesse and melon twisting and acquaintances recall their early ‘impersonators’ (some of of my art college tutors in favour packaging concepts. And for me, dealings with the man, sometimes whom ‘fess up’ in the book) went of long afternoons in the library, there lies Barney Bubbles’ secret, with great poignancy, such as ex- on to define the subsequent I stumbled upon the works of namely his ability to look Stiff Records’ staffer Susan Spiro cultural period, and all of them Eduardo Paolozzi, Constructivism, backwards and forwards at the recalling Bubbles’ ability (me included) owe this man a Krazy Kat, and a strange volume same time, whilst always to see the beauty in everyday huge debt. by Charles Jenks, Adhocism – managing to arrive at The Very objects. There is ample evidence This book is a treasure trove The Case for Improvisation. Point of Now-ness. also that alongside his own for image-makers across all Within a couple of years I noticed As it progresses, the book image-making he was no slouch media, and a reminder that the a similar admix of ideas gives us epoch-defining glimpses when it came to art direction, graphic bombs Barney Bubbles appearing in the work of one of a shuddering cultural drawing on the talents of some dropped are still reverberating. man, but due to his reluctance landscape, clouds of patchouli of the most forward thinking In the words of the late great to credit his artworks, time would oil fade and a new world forms, photographers of the era, Brian Ian Dury: there ain’t half been have to pass before the author’s accompanied by the distinct whiff Griffin and Chris Gabrin amongst some clever bastards. -

The Working Practices of Barney Bubbles | I-D Online 28/09/2010 22:59

PROCESS: The Working Practices of Barney Bubbles | i-D Online 28/09/2010 22:59 Home » i-Spy » PROCESS: The Working Practices of Barney Bubbles search - Published by i-D 11:49 GMT 22/09/10 More + Cited as a major influence to contemporary practitioners including Peter Saville, Malcolm Garrett and Neville Brody, Barney Bubbles was a radical graphic artist. Coinciding with the London Design Festival, last night the CHELSEA Space celebrated its latest exhibition showcasing the working processes of the late master designer. Born Colin Fulcher (he loved a pseudonym and stuck with Bubbles in 67), the enigmatic designer worked across the disciplines of graphic design, painting and music video direction, working with artists including Ian Drury, Elvis Costello, Billy Bragg and Iggy Pop. Referred to as "the missing link between Pop and Culture" by Peter Saville, Bubbles was most renowned for his work with the British independent music scene during the 70s and early 80s. Fellow designer Julian Balme who created sleeves for Madness, Clash and Adam and The Ants and would often visit Bubbles at his studio, told i-D Online, "Bubbles taught me more than any other university lecturer". More + Curated by Paul Gorman, PROCESS includes an array of work never previously shown, most of it borrowed from private collections. The displays are fascinating and represent the varying stages of Bubbles' creative life, including student notebooks, reference materials, his CV, original artwork, books, magazines, paintings, photography, record sleeves, T-shirts, posters, advertisements, badges and stickers and videos directed by Bubbles. Together, the exhibition clearly demonstrates the designer's signature style. -

Class Wargames Class Class Wargames Ludic Ludic Subversion Against Spectacular Capitalism

class wargames Class Wargames ludic Ludic subversion against spectacular capitalism subversion Why should radicals be interested in playing wargames? Surely the Left can have no interest in such militarist fantasies? Yet, Guy Debord – the leader of the Situationist International – placed such importance on his class invention of The Game of War that he described it as the most significant of against his accomplishments. wargames Intrigued by this claim, a multinational group of artists, activists and spectacular academics formed Class Wargames to investigate the political and strategic lessons that could be learnt from playing his ludic experiment. While the ideas of the Situationists continue to be highly influential in the development of subversive art and politics, relatively little attention has been paid to their strategic orientation. Determined to correct this deficiency, Class Wargames is committed to exploring how Debord used the capitalism metaphor of the Napoleonic battlefield to propagate a Situationist analysis of modern society. Inspired by his example, its members have also hacked other military simulations: H.G. Wells’ Little Wars; Chris Peers’ Reds versus Reds and Richard Borg’s Commands & Colors. Playing wargames is not a diversion from politics: it is the training ground of tomorrow’s cybernetic communist insurgents. Fusing together historical research on avant-garde artists, political revolutionaries and military theorists with narratives of five years of public performances, Class Wargames provides a strategic and tactical manual for overthrowing the economic, political and ideological hierarchies of early- 21st century neoliberal capitalism. The knowledge required to create a truly human civilisation is there to be discovered on the game board! richard ludic subversion against barbrook spectacular capitalism Minor Compositions An imprint of Autonomedia Front cover painting: Kimathi Donkor, Toussaint L’Ouverture at Bedourete (2004). -

FREE FESTIVAL 2014 28 August - 14 September

PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL PORTOBELLO FREE FESTIVAL 2014 28 August - 14 September POP UP CINEMA LONDON FILMS W10 5TY ROCK AND ROLL FILMS WESTBOURNE WORLD FILMS STUDIOS KID’S FILMS W10 5JJ VIDEO CAFE KPH ARTISTS W10 6HJ BLEK LE RAT www.portobellofilmfestival.com URBAN MYTHOLOGY/REALITY by Tom Vague Orwell Mansions, on the new become part of the multicultural recalls the Jewish boyfriend of his reputedly last seen at the Globe on Portobello Square W10 Notting Dale slum, along with wife’s sister going round the area Talbot Road and the Mangrove on development off Golborne Road, is English, Irish and Italian on his scooter and reporting back All Saints, and various other local named in allusion to George Orwell communities. to the West Indians on the addresses have claims to being living on Portobello Road (or A hundred years ago, at the whereabouts of the Teds. Hendrix crash pads. possibly the Orwellian style of the outbreak of the First World War the In punk rock mythology the Clash block?). He did indeed begin Electric Cinema was attacked in formed in Portobello market in does, however, have a naval origin. anti-German riots because the 1976. In other versions the pivotal The farm and its lane were named London and Provincial Electric meeting took place on Ladbroke in celebration of England’s defeat Theatres company was German- Grove, various other local streets of Spain in the 1739 battle of owned; not because the manager and the Lisson Grove dole office. Porto Belo (now in Panama), under was suspected of signalling to They did, however, frequent the management of Admiral Zeppelins from the roof. -

DOG MEASURE 070513Web

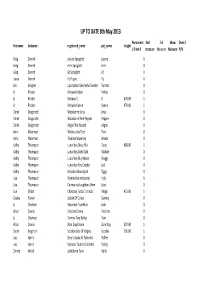

UP TO DATE 8th May 2013 Permanent 2nd 3rd Show Over 2 firstname lastname registered_name pet_name height 1 if not 0 measure Measure Measure Y/N Greg Derrett Jaycee Sproglett Jaycee 0 Greg Derrett Fern Sproglett Fern 0 Greg Derrett Gt Sproglett Gt 0 Laura Derrett FlyPuppy Fly 0 Jim Gregson Lipsmackin Gesviesha Twister Twister 0 Jo Rhodes Moravia Kelbie Kelbie 0 Jo Rhodes Moravia Ci Ci 470.00 1 Jo Rhodes Moravia Kaesie Kaesie 470.00 1 Derek Dragonetti Woodsorrel Jinja Jinja 0 Derek Dragonetti Woodsorrel Red Pepper Pepper 0 Derek Dragonetti Aligan The Wizard Aligan 0 Anne Alderman Wotta Lotta Tosh Tosh 0 Anne Alderman Trueline Waveney Breeze 0 Kathy Thompson Lunarlites Dizzy Mix Dizzy 488.00 1 Kathy Thompson Lunarlites Dark Gold Maddie 0 Kathy Thompson Lunarlites Blue Moon Braggi 0 Kathy Thompson Lunarlites Fire Cracker Jed 0 Kathy Thompson Myndoc Moon Spirit Tiggy 0 Lisa Thompson Wynmallen Indiscreet Indy 0 Lisa Thompson Caninarosa Laughters Here Jake 0 Sue Elliott Chakotay Turbo Tornado Megan 475.00 1 Cayley Turner Splash Of Colour Sammy 0 Jo Chalmers Raeannes True Blue Josh 0 Alison Cronin Fletcher Cronin Fletcher 0 Jo Chalmers Tommy Two Bellies Tom 0 Alison Cronin Zoro Dog Cronin Zoro Dog 507.00 1 Sarah Beighton Scoobie Doo Of Valgray Scoobie 506.00 1 Lois Harris Zero's Aysha At Tolnedra Toffee 0 Lois Harris Starazaz Todd At Tolnedra Toddy 0 Denise Welsh Jadedoren Paris Harlie 0 Cathy Brown Blue Dippy Do Lally Dippy 0 Cathy Brown Dippity Doodah Scooby 0 Soraya Porter Hartsfern In Earnest Ernest 336.00 1 Maureen Goodchild Crystalgorse -

Authenticity, Politics and Post-Punk in Thatcherite Britain

‘Better Decide Which Side You’re On’: Authenticity, Politics and Post-Punk in Thatcherite Britain Doctor of Philosophy (Music) 2014 Joseph O’Connell Joseph O’Connell Acknowledgements Acknowledgements I could not have completed this work without the support and encouragement of my supervisor: Dr Sarah Hill. Alongside your valuable insights and academic expertise, you were also supportive and understanding of a range of personal milestones which took place during the project. I would also like to extend my thanks to other members of the School of Music faculty who offered valuable insight during my research: Dr Kenneth Gloag; Dr Amanda Villepastour; and Prof. David Wyn Jones. My completion of this project would have been impossible without the support of my parents: Denise Arkell and John O’Connell. Without your understanding and backing it would have taken another five years to finish (and nobody wanted that). I would also like to thank my daughter Cecilia for her input during the final twelve months of the project. I look forward to making up for the periods of time we were apart while you allowed me to complete this work. Finally, I would like to thank my wife: Anne-Marie. You were with me every step of the way and remained understanding, supportive and caring throughout. We have been through a lot together during the time it took to complete this thesis, and I am looking forward to many years of looking back and laughing about it all. i Joseph O’Connell Contents Table of Contents Introduction 4 I. Theorizing Politics and Popular Music 1.