Authenticity, Politics and Post-Punk in Thatcherite Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

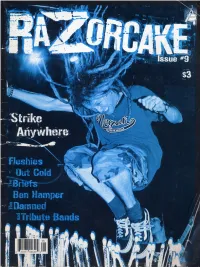

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

Full Pamphlet F+B/C@Start

THE KEY TO DEMOCRATIC REFORM A Genuine Expression of OF THE HOUSE OF LORDS IS SIMPLICITY, VIABILITY AND LEGITIMACY the Will of the People: a viable method of “Following consultation, the government will introduce legislation democratic Lords reform to implement the second phase of the House of Lords reform.” With this single sentence in the 2001 Queen’s Speech, the Labour government gave notice that it was intent on Billy Bragg fulfilling it’s historic commitment to reform the House of Lords. The choice between a democratic second chamber or one which remains predominantly a house of patronage will have to be resolved. Whilst those in favour of the democratic option push for an elected house, supporters of an appointed chamber counter that it would not be sensible for the Commons to legislate so that the House of Lords became a rival chamber. Thus the debate becomes polarised. This pamphlet sets out the case for a viable democratic second chamber that does not challenge the primacy of the House of Commons. BILLY BRAGG is a lifelong supporter of the Labour Party. Songwriter and activist, he was a founder member of RED WEDGE. His recent UK tour was sponsored by the GMB. Born in Essex, he now lives with his family in West Dorset. During the last general election, he set up a tactical voting website which resulted in an end to the Conservative stranglehold in Dorset and the first Labour MP in the county for over 30 years. Published by www.votedorset.net £1.00 A Genuine Expression of the Will of the People A viable method of democratic Lords reform Billy Bragg Published by www.votedorset.net Text ©Billy Bragg 2001 Design & Production: Claire Kendall-Price, Wildcat Publishing (01305 269941) Printed by Friary Press, Dorchester 2 3 It is clear from the commitment batch of peers is created. -

40 Jahre „Damned Damned Damned“ Erstes Punk-Rock-Album Aus U.K

40 Jahre „Damned Damned Damned“ Erstes Punk-Rock-Album aus U.K. neu aufgelegt 07. Februar 2017, Von: Redaktion Die 1976 in Großbritannien gegründete Punkband The Damned zählt auf mehreren Ebenen zu den Pionieren der dortigen Szene. Am 18.Februar 1977 veröffentlichte die Band mit „Damned Damned Damned“ ihr Debütalbum. The Damned waren die erste britische Punkband mit einem Plattenvertrag, einer Single-Veröffentlichung und einem Album. Fast auf den Tag genau 40 Jahre nach Veröffentlichung ihres legendären Debüts – am 17.Februar 2017- erscheint das Album neu. Remastered und in neuer, erweiterter Aufmachung. Dem britischen Label Stiff Records war es vorbehalten, am 18.Februar 1977 das erste Punk-Album einer Band aus England auf den Markt zu bringen: „Damned Damned Damned“ von The Damned. Die Band um Dave Vanian, Captain Sensible (in den Achtzigern außerdem als Solo-Künstler bekannt), Brian James und Rat Scabies waren in vielen Belangen Punk-Vorreiter in ihrem Heimatland. The Damned waren die erste Band ihres Genres mit einem Plattenvertrag, ihre Song „New Rose“ war die erste Punk-Single, besagtes Album ebenfalls das erste im britischen Punk, zudem waren The Damned die erste UK-Punk-Formation, die in den USA auf Tournee ging.Zum 40-jährigen Jubiläum von „Damned Damned Damned“ erscheint dieses in der Punk-Historie Großbritanniens so relevante Werk neu gemastert, mit neuen Liner-Notes und 28-seitigem Booklet. Als Vinyl-Langspielplatte ist das Ganze ebenfalls zu haben. Eine besondere Anekdote dürfte sein, dass der Journalist John Ingham, 1977 erster Rezensent des The-Damned-Albums die Liner-Notes zu der Wiederveröffentlichung geschrieben hat. Um die Entstehung der Songs und die Auswirkungen, die die ursprüngliche Album-Veröffentlichung zur Folge hatte eingehender zu beleuchten, führte John Ingham nochmals Interviews mit den Bandmitgliedern. -

BILLY BRAGG Stereo MC’S Tiggs Da Author Rag ‘N’ Bone Man

PRESENTS 2016 BILLY BRAGG Stereo MC’s Tiggs Da Author Rag ‘N’ Bone Man Your guide to this year’s festival PLUS Reviews, Interviews and much more! 1 12 ARTIST VILLAGE AND SMALL SCULPTURE SHOW MAP 2016 Queue to buy tickets on the day BOX OFFICE LEIGH-ON-SEA CC CHALKWELL PARK VILLAGE ROOMS BEACH GREEN HUT STAGE IDEA13 PICNIC STAGE STAGE AREA 1 SHOW TENNIS GROUND 2 5 COURTS FIRST AID TEATRO METAL BBC 3 VERDI ART ESSEX 12 MARKET CYCLE WESTCLIFF STAGE SCHOOL OAK VILLAGE 6 -ON-SEA CC POLICE PLACE STAGE SKATE PARK 11 7 GLOBAL INFO VILLAGE POINT 10 4 ESTUARY FIRST AID ART GROUP METAL & LOSTMISSING EXHIBITION ART 8 MINI CHALKWELL HALL SCHOOL CHILDERNPERSONS 9 GREEN (BUILDING) TOILETS RIVERSIDE MINI GREEN 9 JULY 2016 CHALKWELL PARK 11AM - 10PM PRESS & STAGE TO CHALKWELL STATION PRODUCTION STAGE villagegreen16 www.villagegreenfestival.com Twitter: @vg_festival vg16 Instagram: villagegreenfestival Facebook: villagegreenfestival 1 Alexis Zelda Stevens 4 Redhawk Logistica 7 Cool Diabang & Sonja Kandels 10 Josh Langan 2 Cool Diabang 5 Luke Gottelier (performance at 4.15) 11 John Wallbank 8 Julia McKinlay 3 Stuart Bowditch 6 Luke Gottelier 12 Small Sculpture Show 9 Stuart Bowditch VILLAGE GREEN STAGE RIVERSIDE STAGE MIDDLE AGE SPREAD DJs URBAN ALLSTARS DJs This collective of popular DJs sell out every gig The mighty Urban Allstars, spinning all things they do, and they’re bringing their floor-filling skills funky on the decks to get you into the groove. to work the park. BLACK CAT DJs 11.50 - 12.20 PETTY PHASE The band of Soul Brothers will be serving up a All the musical unpredictability and charisma that sexy platter of Rhythm & Blues, Northern Soul, girl punks should have, plus some. -

Towards an Understanding of the Contemporary Artist-Led Collective

The Ecology of Cultural Space: Towards an Understanding of the Contemporary Artist-led Collective John David Wright University of Leeds School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2019 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of John David Wright to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 1 Acknowledgments Thank you to my supervisors, Professor Abigail Harrison Moore and Professor Chris Taylor, for being both critical and constructive throughout. Thank you to members of Assemble and the team at The Baltic Street Playground for being incredibly welcoming, even when I asked strange questions. I would like to especially acknowledge Fran Edgerley for agreeing to help build a Yarn Community dialogue and showing me Sugarhouse Studios. A big thank you to The Cool Couple for engaging in construcutive debate on wide-ranging subject matter. A special mention for all those involved in the mapping study, you all responded promptly to my updates. Thank you to the members of the Retro Bar at the End of the Universe, you are my friends and fellow artivists! I would like to acknowledge the continued support I have received from the academic community in the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies. -

New Books on Art & Culture

S11_cover_OUT.qxp:cat_s05_cover1 12/2/10 3:13 PM Page 1 Presorted | Bound Printed DISTRIBUTEDARTPUBLISHERS,INC Matter U.S. Postage PAID Madison, WI Permit No. 2223 DISTRIBUTEDARTPUBLISHERS . SPRING 2011 NEW BOOKS ON SPRING 2011 BOOKS ON ART AND CULTURE ART & CULTURE ISBN 978-1-935202-48-6 $3.50 DISTRIBUTED ART PUBLISHERS, INC. 155 SIXTH AVENUE 2ND FLOOR NEW YORK NY 10013 WWW.ARTBOOK.COM GENERAL INTEREST GeneralInterest 4 SPRING HIGHLIGHTS ArtHistory 64 Art 76 BookDesign 88 Photography 90 Writings&GroupExhibitions 102 Architecture&Design 110 Journals 118 MORE NEW BOOKS ON ART & CULTURE Special&LimitedEditions 124 Art 125 GroupExhibitions 147 Photography 157 Catalogue Editor Thomas Evans Architecture&Design 169 Art Direction Stacy Wakefield Forte Image Production Nicole Lee BacklistHighlights 175 Data Production Index 179 Alexa Forosty Copy Writing Sara Marcus Cameron Shaw Eleanor Strehl Printing Royle Printing Front cover image: Mark Morrisroe,“Fascination (Jonathan),” c. 1983. C-print, negative sandwich, 40.6 x 50.8 cm. F.C. Gundlach Foundation. © The Estate of Mark Morrisroe (Ringier Collection) at Fotomuseum Winterthur. From Mark Morrisroe, published by JRP|Ringier. See Page 6. Back cover image: Rodney Graham,“Weathervane (West),” 2007. From Rodney Graham: British Weathervanes, published by Christine Burgin/Donald Young. See page 87. Takashi Murakami,“Flower Matango” (2001–2006), in the Galerie des Glaces at Versailles. See Murakami Versailles, published by Editions Xavier Barral, p. 16. GENERAL INTEREST 4 | D.A.P. | T:800.338.2665 F:800.478.3128 GENERAL INTEREST Drawn from the collection of the Library of Congress, this beautifully produced book is a celebration of the history of the photographic album, from the turn of last century to the present day. -

ARTS EVENTS the Talbot Theatre Whitchurch Leisure Centre Heath Road SY13 2BY 01948 660660

ARTS EVENTS The Talbot Theatre Whitchurch Leisure Centre Heath Road SY13 2BY 01948 660660 TUESDAY 26TH APRIL 7.30PM ‘THE DRESSMAKER’ (12A) 1hr 58mins A stylish drama based on Rosalie Ham’s best-selling novel. The Dressmaker is the story of femme fatale Tilly Dunnage (Kate Winslet) who returns to her small hometown in the country to right the wrongs of the past. TUESDAY 3RD MAY 7.30PM ‘DAD’S ARMY’ (U) 1hr 40 mins A cinema remake of the classic sitcom with a stellar cast including Michael Gambon, Toby Jones, Bill Nighy, Catherine Zeta Jones and Tom Courtenay. The Walmington-on-Sea Home Guard platoon deal with a visiting female journalist and a German spy at the end of World War II. FRIDAY 20TH MAY 7.30PM ‘A WALK IN THE WOODS’ (15) 1hr 45 mins This biographical adventure-comedy will be shown in conjunction with Whitchurch Walking Festival. After spending two decades in England, Bill Byson returns to the US where he decides that the best way to connect with his homeland is to hike the Appalachian Trail with one of his oldest friends. SATURDAY 21ST MAY 8PM NORTH SHROPSHIRE FOLK PRESENTS ‘SAM CARTER’ Sam Carter is a singer/songwriter in constant demand for his captivating live performances. A Horizon Award-winner for Best Newcomer at the 2010 BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards, he has toured with Bellowhead and performs with Jim Moray in their new contemporary electric folk band False Lights. ‘The finest English-style finger-picking guitarist of his generation’ - Jon Boden. Tickets £12 (£10) TUESDAY 24TH MAY 7.30PM ‘SPOTLIGHT’ (15) 2 hrs 8mins Winner of Best Picture at the Oscars and Best Original Screenplay at both the Oscars and BAFTAs. -

Dougie Maclean the Wilson Family Granny’S Attic Mrsackroyd Rheingans Sisters Moore, Moss & Rutter Anthony John Clarke

Cleckheaton, West Yorkshire Dougie MacLean The Wilson Family Granny’s Attic MrsAckroyd Rheingans Sisters Moore, Moss & Rutter Anthony John Clarke Concerts, Singarounds, Ceilidh, Parade, Morris Sides, Sunday Fun Day, Street Entertainment and lots lots more … A warm and friendly Festival in the heart of West Yorkshire Come along and join in the fun Supported by Online Tickets from Dougie MacLean (Sat 7th July 2018) “Dougie MacLean is Scotland's pre-eminent singer-songwriter and a national musical treasure” (SingOut USA) who has developed a unique blend of lyrical, 'roots based' songwriting and instrumental composition. He is internationally renowned for his song 'Caledonia', music for 'Last of the Mohicans' and inspired performances. His songs have been covered by Paolo Nutini, Amy MacDonald, Ronan Keating, Mary Black, Frankie Miller, Cara Dillon, Kathy Mattea and many other top performers. He has received two prestigious Tartan Clef Awards, a place in the Scottish Music Hall of Fame, a Lifetime Achievement Award from BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards and an OBE! The Wilson Family (Saturday 7th July 2018) The Wilson Family were very honoured to be the latest recipients to have been awarded the EFDSS Gold Badge Award in October 2017. The glorious, powerful, vocal harmony of The Wilson Family of Billingham, Teesside has rung out in folk clubs and festivals continuously for the last 40+ years. The Brothers sing traditional and traditionally-orientated songs, with deep understanding, joy and good humour. It will be good to have them back in Cleckheaton Granny’s Attic (Sat 7th July 2018) Cohen Braithwaite-Kilcoyne (Melodeon, Concertina, Vocals), George Sansome (Guitar, Vocals) and Lewis Wood (Fiddle, Vocals) – are a folk trio who play the tradition with verve, energy and their own inimitable style. -

Mark's Music Notes for December 2011…

MARK’S MUSIC NOTES FOR DECEMBER 2011… The Black Keys follow up their excellent 2010 album Brothers with the upbeat El Camino, another great album that commercial radio will probably ignore just like it did with Brothers. In a day and age where CD sales are on the decline, record labels continue to re-issue classic titles with proven track records in new incarnations that include unreleased material, re-mastered sound, and often lavish box sets. Though not yet included in Music Notes, Pink Floyd and Queen both had their entire catalogs re-vamped this year, and they sound great. Jethro Tull’s classic Aqualung album has been expanded, re-mixed and re-mastered with the level of care and quality that should be the standard for all re-issues. The Rolling Stones have already released expanded remasters and box sets on Exile On Main Street and Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out, and now their top selling album, Some Girls has received the same treatment. Be Bop Deluxe is a 1970’s band that most readers will be unfamiliar with. They never had any mainstream success in the U.S., but the band had several great albums, and their entire studio catalog has recently been remastered and compiled into a concise box set. The Black Keys – El Camino Vocalist/guitarist Dan Auerbach and Drummer Patrick Carney of The Black Keys, have said that they have been listening to a lot of Rolling Stones lately, and they set out to record a more direct rock and roll album than their last album, Brothers was. -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

The Creation of a New Dignity Work Force Building Peace After Conflict

Building Peace After Conflict “Envisioning Hope” . A Proposal for UNDP: The Creation of a New Dignity Work Force For Post Conflict Development and to Create a Culture of Peace Based on Lessons Learned in the Last Decade by Barbara C. Bodine December, 2010 " If the international community wants to restore hope in a country or region emerging from violent conflict by supporting and nurtiring a peaceful resolution, it will have to pay special attention to the long-term prospects of the military and the warlords who are about to lose their livelihoods. Supporting a demobilization process is not just a technical military issue. It is a complex operation that has political, security, humanitarian and development dimensions as well. If one aspect of this pentagram is neglected, the entire peace process may unravel." —Dirk Salomons, "Security: An Absolute Prerequisite," Chapter Two in Post Conflict Development: Meeting New Challenges, edited by Gerd Junne & Willemijn Verkoren (Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Reinner Publishers, 2005), p.20. Introduction: Sharing a Sense of Mission with Local Communities Empowering local communities and governance for the design and implementation of post conflict development models is at the core of success. How stable locally-based governance mechanisms are can often be determined by the concurrent parallel ways that national and international governments support their efforts. These very real and practical problems demand open communication and the ability to work with local knowledge. State building at the grassroots level through district offices and centers may be the best place to start up new development models. Within villages and districts, tribal groups and ethnic alliances, the access to local population and thoughts are more direct and immediate. -

ROC136.Guit T.Pdf

100 GREATEST GUITARISTS Hammett: oNe iN A MiLLioN “innovative”. KiRK HaMMEtt By Ol Drake For me, Kirk Hammett is one of the More stars on their top guitarists greatest metal guitarists ever – and also one at classicrock of the most underrated. The thing about magazine.co.uk his playing is that, while he can certainly shred, that’s not all he does. Kirk has his own voice and style – and to me, that’s ADMiRABLe NeLSoN instantly recognisable. BiLL NELsON The problem is that everyone knows By Brian Tatler Metallica’s songs so well that what he contributes is overlooked. More than that, Bill Nelson was one of my favourite people take him for granted. You walk guitarists in the 1970s. I used to into a guitar shop at any time, and the } listen to Be Bop Deluxe albums a lot, chances are you’ll hear someone “Davy O’List’s and Bill’s solos always seemed very playing one of his solos, from a song tasteful, not bluesy, just kind of like One. And there will always be guitar playing soaring. I really liked his playing and a bright spark going: “That’s just was incendiary, some of it rubbed off on my boring. Anyone can play that.” The technique, particularly songs such as point is that not everyone can play borderline Jet Silver (And The Dolls Of Venus), what Kirk did on something like One, psychotic. Maid In Heaven and Crying To The Sky and he also came up with it in the first – they all had these fabulous, place.