What Should Schools Teach? ‘This Book Brings Profound Questions About What Children Need to Know Back to the Centre of Educational Enquiry Where They Belong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Responsibilities of the Secretary of State for Education

House of Commons Education Committee The Responsibilities of the Secretary of State for Education Oral Evidence Tuesday 24 April 2012 Rt Hon Michael Gove MP, Secretary of State for Education Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 24 April 2012 HC 1786-II Published on 26 June 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £5.50 Education Committee: Evidence Ev 29 Tuesday 24 April 2012 Members present: Mr Graham Stuart (Chair) Alex Cunningham Ian Mearns Damian Hinds Lisa Nandy Charlotte Leslie Craig Whittaker ________________ Examination of Witness Witness: Rt Hon Michael Gove MP, Secretary of State for Education, gave evidence. Q196 Chair: Good morning, Secretary of State. critical. If there is one unifying theme, and I suspect Thank you very much for joining us. Having been Sir Michael would agree, it is that the most effective caught short in our last lesson and now being late for form of school improvement is school to school, peer this one, there were suggestions of detention for to peer, professional to professional. We want to see further questioning, but we are delighted to have you serving head teachers and other school leaders playing with us. If I may, I will start just by asking you about a central role. what the Head of Ofsted told us when he recently gave evidence. He said, “It seems to me there needs Q198 Chair: On that basis, are you disappointed that to be some sort of intermediary layer that finds out so few of the converter academies—the outstanding what is happening on the ground and intervenes and very strong schools that have converted to before it is too late. -

Geography for the IB DIPLOMA

OXFORD IB STUDY GUIDES Garrett Nagle Briony Cooke Geography FOR THE IB DIPLOMA 2nd edition OPTION A FRESHWATER – DRAINAGE BASINS 1 DRAINAGE BASIN HYDROLOGY AND GEOMORPHOLOGY The drainage basin DEFINITIONS Evaporation is the physical process by which a liquid becomes a gas. It is a function of: The drainage basin is an area that is drained by a river • vapour pressure and its tributaries. Drainage basins have inputs, stores, • air temperature processes and outputs. The inputs and outputs cross the • wind boundary of the drainage basin, hence the drainage basin • rock surface, for example, bare soils and rocks have is an open system. The main input is precipitation, which is high rates of evaporation compared with surfaces regulated by various means of storage. The outputs include which have a protective tilth where rates are low. evaporation and transpiration. Flows include infiltration, throughflow, overland flow and base flow, and stores Transpiration is the loss of water from vegetation. include vegetation, soil, aquifers and the cryosphere (snow Evapotranspiration is the combined loss of water and ice). from vegetation and water surfaces to the atmosphere. Drainage basin hydrology Potential evapotranspiration is the rate of water loss from an area if there were no shortage of water. PRECIPITATION Channel Interception precipitation 1. VEGETATION FLOWS Stemflow & throughfall Infiltration is the process by which water sinks into the Overland flow 2. SURFACE STORAGE 5. CHANNEL ground. Infiltration capacity refers to the amount of Floods moisture that a soil can hold. By contrast, the infiltration Capilliary Infiltration rise rate refers to the speed with which water can enter the Interflow 3. -

AMSTATNEWS the Membership Magazine of the American Statistical Association •

January 2015 • Issue #451 AMSTATNEWS The Membership Magazine of the American Statistical Association • http://magazine.amstat.org AN UPDATE to the American Community Survey Program ALSO: Guidelines for Undergraduate Programs in Statistical Science Updated Meet Brian Moyer, Director of the Bureau of Economic Analysis AMSTATNEWS JANUARY 2015 • ISSUE #451 Executive Director Ron Wasserstein: [email protected] Associate Executive Director and Director of Operations Stephen Porzio: [email protected] features Director of Science Policy 3 President’s Corner Steve Pierson: [email protected] 5 Highlights of the November 2014 ASA Board of Directors Director of Education Meeting Rebecca Nichols: [email protected] 7 ASA Leaders Reminisce: Meet ASA Past President Managing Editor Megan Murphy: [email protected] Marie Davidian Production Coordinators/Graphic Designers 11 Benefits of the New All-Member Forum Sara Davidson: [email protected] Megan Ruyle: [email protected] 12 ASA, STATS.org Partner to Help Raise Media Statistical Literacy Publications Coordinator 13 White House Issues Policy Directive Bolstering Federal Val Nirala: [email protected] Statistical Agencies Advertising Manager 14 An Update to the American Community Survey Program Claudine Donovan: [email protected] 17 CHANCE Highlights: Special Issue Devoted to Women in Contributing Staff Members Statistics Jeff Myers • Amy Farris • Alison Smith 18 JQAS Highlights: Football, Golf, Soccer, Fly-Fishing Featured Amstat News welcomes news items and letters from readers on matters in December Issue of interest to the association and the profession. Address correspondence to Managing Editor, Amstat News, American Statistical Association, 732 North Washington Street, Alexandria VA 22314-1943 USA, or email amstat@ 19 NISS Meeting Addresses Transition amstat.org. -

Developing Statistical Literacy in Mathematics Education?

Iddo GAL, Haifa Developing statistical literacy in mathematics education? Navigating between current gaps and new needs and contents Abstract: This paper summarizes selected points raised during my plenary talk, which examined challenges facing the promotion of statistical literacy and statistical ideas within mathematics education, and pointed to some new developments related to statistical literacy. The paper focuses on one of these new developments, i.e., ideas regarding the knowledge and skills related to engaging with "civic statistics", based on work by ProCivicStat project, and on some implications. Introduction: About statistical literacy The place of statistics education within mathematics education has been problematic for many years, and continues to challenge mathematics educators and mathematicians, as well as school systems. This is despite the fact that "Data and Chance," "Statistics and Probability," or "Stochastics" are a major sub-area in the mathematics curriculum in all western countries. Within the domain of statistics education, teaching for the development of statistical literacy has a special place. Statistical literacy is a construct related to adult numeracy (Gal, 1997) and mathematical literacy, but goes beyond them. It refers to comprehension of and engagement with statistical messages that may appear in the media, at work, and other contexts. Statistical Literacy has been defined in several ways in the literature (Haack, 1979). My own definition (Gal, 2002) reads: “The motivation and ability to access, understand, interpret, critically evaluate, and if relevant express opinions, regarding statistical messages, data-related arguments, or issues involving uncertainty and risk” The definition above implies that statistical literacy is part of a larger family of "literacies" or competencies that all adults are expected to possess, including not only numeracy but also scientific literacy, financial literacy, health literacy, and more. -

Open PDF 260KB

Education Committee Oral evidence: Accountability hearings, HC 262 Tuesday 10 November 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 10 November 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Robert Halfon (Chair); Apsana Begum; Dawn Butler; Jonathan Gullis; Tom Hunt; Dr Caroline Johnson; Kim Johnson; David Johnston; Ian Mearns; David Simmonds; Christian Wakeford. Questions 417 - 515 Witnesses I: Amanda Spielman, Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector, Ofsted; and Yvette Stanley, National Director, Regulation and Social Care, Ofsted. Written evidence from witnesses: – [Add names of witnesses and hyperlink to submissions] Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Amanda Spielman and Yvette Stanley. Q417 Chair: Good morning, everyone. We are very pleased to have Ofsted here today addressing our Committee. For the benefit of the tape and those who are watching on the internet, could you kindly give your names and your position, and also if you are happy for us to address you with first names or whether you would like your full address. Amanda Spielman: I am very happy to be addressed by my first name. I am Amanda Spielman, and I am the Ofsted Chief Inspector. Yvette Stanley: Yvette Stanley, happy to be “Yvette”. I am the National Director for Regulation and Social Care at Ofsted. Q418 Chair: Thank you. Amanda, you published a report today. For the benefit of those watching, can you set out the key conclusions, as we have only heard what has been in the media? Amanda Spielman: We published a set of reports on early years, schools, further education, and children with special educational needs and disabilities. -

Play and No Work? a 'Ludistory' of the Curatorial As Transitional Object at the Early

All Play and No Work? A ‘Ludistory’ of the Curatorial as Transitional Object at the Early ICA Ben Cranfield Tate Papers no.22 Using the idea of play to animate fragments from the archive of the Institute of Contemporary Arts, this paper draws upon notions of ‘ludistory’ and the ‘transitional object’ to argue that play is not just the opposite of adult work, but may instead be understood as a radical act of contemporary and contingent searching. It is impossible to examine changes in culture and its meaning in the post-war period without encountering the idea of play as an ideal mode and level of experience. From the publication in English of historian Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens in 1949 to the appearance of writer Richard Neville’s Play Power in 1970, play was used to signify an enduring and repressed part of human life that had the power to unite and oppose, nurture and destroy in equal measure.1 Play, as related by Huizinga to freedom, non- instrumentality and irrationality, resonated with the surrealist roots of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London and its attendant interest in the pre-conscious and unconscious.2 Although Huizinga and Neville did not believe play to be the exclusive preserve of childhood, a concern for child development and for the role of play in childhood grew in the post-war period. As historian Roy Kozlovsky has argued, the idea of play as an intrinsic and vital part of child development and as something that could be enhanced through policy making was enshrined within the 1959 Declaration of the -

Party Parliamentary Group on Ending Homelessness

All Party Parliamentary Group on Ending Homelessness Emergency COVID-19 measures – Officers Meeting Minutes 13 July 2020, 10-11.30am, Zoom Attendees: Apologies: Neil Coyle MP, APPG Co-Chair Jason McCartney MP Bob Blackman MP, APPG Co-Chair Steve McCabe MP Lord Shipley Julie Marson MP Ben Everitt MP Stephen Timms MP Sally-Ann Hart MP Rosie Duffield MP Baroness Healy of Primrose Hill Debbie Abrahams MP Lord Holmes of Richmond Andrew Selous MP Lord Young of Cookham Kevin Hollinrake MP Feryal Clark MP Nickie Aiken MP Richard Graham MP Parliamentary Assistants: Layla Moran MP Graeme Smith, Office of Neil Coyle MP Damian Hinds MP James Sweeney, Office of Matt Western MP Tommy Sheppard MP Gail Harris, Office of Shaun Bailey MP Peter Dowd MP Harriette Drew, Office of Barry Sheerman MP Steve Baker MP Tom Leach, Office of Kate Osborne MP Tonia Antoniazzi MP Hannah Cawley, Office of Paul Blomfield MP Freddie Evans, Office of Geraint Davies MP Greg Oxley, Office of Eddie Hughes MP Sarah Doyle, Office of Kim Johnson MP Secretariat: Panellists: Emily Batchelor, Secretariat to APPG Matt Downie, Crisis Other: Liz Davies, Garden Court Chambers Jasmine Basran, Crisis Adrian Berry, Garden Court Chambers Ruth Jacob, Crisis Hannah Gousy, Crisis Cllr Kieron William, Southwark Council Disha Bhatt, Crisis Cabinet Member for Housing Management Saskia Neibig, Crisis and Modernisation Hannah Slater, Crisis Neil Munslow, Newcastle City Council Robyn Casey, Policy and Public Affairs Alison Butler, Croydon Council Manager at St. Mungo’s Chris Coffey, Porchlight Elisabeth Garratt, University of Sheffield Tim Sigsworth, AKT Jo Bhandal, AKT Anna Yassin, Glass Door Paul Anders, Public Health England Marike Van Harskamp, New Horizon Youth Centre Burcu Borysik, Revolving Doors Agency Kady Murphy, Just for Kids Law Emma Cookson, St. -

Refugees Welcome? the Experience of New Refugees in the UK a Report by the All Party Parliamentary Group on Refugees

Refugees Welcome? The Experience of New Refugees in the UK A report by the All Party Parliamentary Group on Refugees April 2017 This is not an official publication of the House of Commons or the House of Lords. It has not been approved by either House or its committees. All-Party Parliamentary Groups are informal groups of Members of both Houses with a common interest in particular issues. The views expressed in this report are those of the inquiry panel only, acting in a personal capacity, based on the evidence they received and heard during the inquiry. The printing costs of the report were funded by the Barrow Cadbury Trust. Refugees Welcome? 2 Refugees Welcome? About the All Party About the inquiry Parliamentary Group This inquiry was carried out by a panel of Parliamentarians on behalf of the APPG on Refugees, with support provided by the Refugee Council. The panel consisted on Refugees of members of the House of Commons and the House of Lords. They were: The All Party Parliamentary Group on Refugees brings together Parliamentarians from all political parties with Thangam Debbonnaire MP (Labour) – an interest in refugees. The group’s mission is to provide Chair of the APPG on Refugees and the inquiry a forum for the discussion of issues relating to refugees, Lord David Alton (Crossbench) both in the UK and abroad, and to promote the welfare of refugees. David Burrowes MP (Conservative) Secretariat support is provided to the All Party Lord Alf Dubs (Labour) Parliamentary Group by the charity The Refugee Council. Paul Butler, the Bishop of Durham For more information about the All Party Parliamentary Group, Baroness Barbara Janke (Liberal Democrat) please contact [email protected]. -

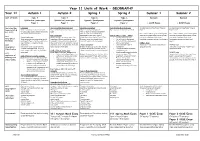

Year 11 Units of Work - GEOGRAPHY Year 11 Autumn 1 Autumn 2 Spring 1 Spring 2 Summer 1 Summer 2

Year 11 Units of Work - GEOGRAPHY Year 11 Autumn 1 Autumn 2 Spring 1 Spring 2 Summer 1 Summer 2 Unit of Work Topic 3 Topic 3 Topic 6 Topic 6 Revision Revision Distinctive Landscapes Distinctive Landscapes Dynamic Development Dynamic Development Paper 1 Paper 1 Paper 2 Paper 2 + GCSE Exams + GCSE Exams Curriculum Map Landscapes Year 11 Autumn Mock Exam week Measuring development Year 11Spring Mock Exam week In class revision with particular focus on In class revision with particular focus on (Links to OCR B What is a landscape (natural and built) Topics 3,4,5,7 and human fieldwork practice What is meant by development? Paper 3 practice linked to topics 4,6,8 Paper 1. Paper 2 and 3. 9-1 GCSE) UK Landscapes (upland, lowland and glacial) – paper What is meant by uneven development? distribution and characteristics How can countries be classified by Use revision booklets, green revision guides Use revision booklets, green revision guides River Landscapes development?(AC’s, EDC’s, LIDC’s) CASE STUDY of a LIDC – Zambia and other strategies such as quick quizzes, and other strategies such as quick quizzes, AO1 Coastal Landscapes What geomorphic processes shape river Global distribution of AC’s, EDC’s, LIDC’s Location and background case study mind-maps, flash cards, case study mind-maps, flash cards, Geographical What geomorphic processes shape coastal landscapes? (Erosion, weathering, mass Economic, social, environmental and Current level of development knowledge organisers and use of past papers knowledge organisers and use of past Knowledge landscapes? (Types of erosion, weathering, movement, transportation and deposition) combined measures of development. -

Adult Literacy Programs of the Future

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 317 976 CS 010 024 AUTHOR Powell, William R. TITLE Adult Literacy Programs of the Future. PUB DATE May 90 NOTE 23p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Reading AssociatIon (35th, Atlanta, GA, May 6-11, 1990). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) -- Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Eduilation; *Adult Literacy; Educational Policy; Functiclal Literacy; *Futures (of Society); *Government Role; *Literacy; World Problems ABSTRACT The retention factor of literacy must be the target variable in any projection of literacy programs of the future. Further, the success of literacy programs of the future is contingent upon the resolution of three major problem areas:(1) the concept of literacy;(2) the programs of literacy; and (3) the politics of literacy. A concept of literacy is needed for the stabilization of what precisely constitutes literacy. A concept provides a more enduring description, definitions do riot. The central issue is: When is an individual permanently literate, now and forever? The adult literacy efforts of the past have been piece-meal, haphazard, and spasmodic at best. This is not to belittle the remarkable attempts, but only to admit the obvious. The fact that the level of basic literacy is attainable for nearly 100% of any population in any culture in any sovereign country does not speak well for the governing groups which are responsible for education. Governmental commitment, professional involvement, and "turfism" will have to change to enhance the future of adult literacy programs. (One figure is included; 18 references are attached.) (RS) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

King Mob Echo: from Gordon Riots to Situationists & Sex Pistols

KING MOB ECHO FROM 1780 GORDON RIOTS TO SITUATIONISTS SEX PISTOLS AND BEYOND BY TOM VAGUE INCOMPLETE WORKS OF KING MOB WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES DARK STAR LONDON ·- - � --- Printed by Polestar AUP Aberdeen Limited, Rareness Rd., Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen AB12 3LE § 11JJJDJJDILIEJMIIENf1r 1f(Q) KIINCGr JMI(Q)IB3 JECCIHI(Q) ENGLISH SECTION OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL IF([J)IF ffiIE V ([J) IL lUilII ([J) W §IFIEIEIIJ) IHIII§il([J) ffiY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY DEREK HARRIS AND MALCOLM HOPKINS Illustrations: 'The Riots in Moorfields' (cover), 'The London Riots', 'at Langdale's' by 'Phiz' Hablot K. Browne, Horwood's 1792-9 'Plan of London', 'The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle', 'Oliver Twist Manifesto' by Malcolm McLaren. Vagrants and historical shout outs: Sandra Belgrave, Stewart Home, Mark Jackson, Mark Saunders, Joe D. Stevens at NDTC, Boz & Phiz, J. Paul de Castro, Blue Bredren, Cockney Visionaries, Dempsey, Boss Goodman, Lord George Gordon, Chris Gray, Jonathon Green, Jefferson Hack, Christopher Hibbert, Hoppy, Ian Gilmour, Ish, Dzifa & Simone at The Grape, Barry Jennings, Joe Jones, Shaun Kerr, Layla, Lucas, Malcolm McLaren, John Mead, Simon Morrissey, Don Nicholson-Smith, Michel Prigent (pre-publicity), Charlie Radcliffe, Jamie Reid, George Robertson & Melinda Mash, Dragan Rad, George Rude, Naveen Saleh, Jon Savage, Valerie Solanas, Carolyn Starren & co at Kensington Library, Mark Stewart, Toko, Alex Trocchi, Fred & Judy Vermorel, Warren, Dr. Watson, Viv Westwood, Jack Wilkes, Dave & Stuart Wise Soundtrack: 'It's a London Thing' Scott Garcia, 'Going Mobile' The Who, 'Living for the City' Stevie Wonder, 'Boston Tea Party' Alex Harvey, 'Catholic Day' Adam and the Ants, 'Do the Strand' Roxy Music', 'Rev. -

Contem Porary Spring 07 Madcap's Last Laugh

Syd Prog:Nitin Prog 4/5/07 13:05 Page 1 barbican do something different Only Connect Tonight’s concert is part of the only connect series, the Barbican’s innovative series that c brings together the worlds of film, music and art by inviting exceptional musicians, composers, o artists and filmmakers to develop collaborations and present new work. n ‘Give a big hand to Only Connect, a series of events designed to cross borders and break Syd t down barriers, challenge idle preconception and encourage exceptional artists to experiment, e collaborate, provoke, stimulate and entertain.’ Time Out m For more details visit www.barbican.org.uk/onlyconnect p Barrett o The Barbican Centre is r There will be an interval in tonight’s concert. provided by the City of a Madcap’s London Corporation as No smoking in the auditorium. No cameras, part of its contribution to tape recorders or other recording the cultural life of London r equipment may be taken into the hall. and the nation. y Last Laugh s p do something different r i Find out n before they g Thu 10 May 7.30pm sell out! 0 7 E–updates Celebrating the th The easy way to hear about the arts www.barbican.org.uk/contemporary Barbican’s 25 birthday events and offers www.barbican.org.uk/25 Sign up at Free programme The Barbican is 25 in 2007 and to help celebrate we have arranged www.barbican.org.uk/e-updates a wide variety of special events and activities. This year’s Barbican contemporary Visit www.barbican.org.uk/25 music events are on sale now.