Does River Restoration Work? Taxonomic and Functional Trajectories at Two Restoration Schemes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geography for the IB DIPLOMA

OXFORD IB STUDY GUIDES Garrett Nagle Briony Cooke Geography FOR THE IB DIPLOMA 2nd edition OPTION A FRESHWATER – DRAINAGE BASINS 1 DRAINAGE BASIN HYDROLOGY AND GEOMORPHOLOGY The drainage basin DEFINITIONS Evaporation is the physical process by which a liquid becomes a gas. It is a function of: The drainage basin is an area that is drained by a river • vapour pressure and its tributaries. Drainage basins have inputs, stores, • air temperature processes and outputs. The inputs and outputs cross the • wind boundary of the drainage basin, hence the drainage basin • rock surface, for example, bare soils and rocks have is an open system. The main input is precipitation, which is high rates of evaporation compared with surfaces regulated by various means of storage. The outputs include which have a protective tilth where rates are low. evaporation and transpiration. Flows include infiltration, throughflow, overland flow and base flow, and stores Transpiration is the loss of water from vegetation. include vegetation, soil, aquifers and the cryosphere (snow Evapotranspiration is the combined loss of water and ice). from vegetation and water surfaces to the atmosphere. Drainage basin hydrology Potential evapotranspiration is the rate of water loss from an area if there were no shortage of water. PRECIPITATION Channel Interception precipitation 1. VEGETATION FLOWS Stemflow & throughfall Infiltration is the process by which water sinks into the Overland flow 2. SURFACE STORAGE 5. CHANNEL ground. Infiltration capacity refers to the amount of Floods moisture that a soil can hold. By contrast, the infiltration Capilliary Infiltration rise rate refers to the speed with which water can enter the Interflow 3. -

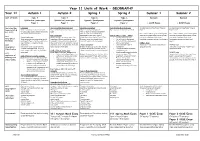

Year 11 Units of Work - GEOGRAPHY Year 11 Autumn 1 Autumn 2 Spring 1 Spring 2 Summer 1 Summer 2

Year 11 Units of Work - GEOGRAPHY Year 11 Autumn 1 Autumn 2 Spring 1 Spring 2 Summer 1 Summer 2 Unit of Work Topic 3 Topic 3 Topic 6 Topic 6 Revision Revision Distinctive Landscapes Distinctive Landscapes Dynamic Development Dynamic Development Paper 1 Paper 1 Paper 2 Paper 2 + GCSE Exams + GCSE Exams Curriculum Map Landscapes Year 11 Autumn Mock Exam week Measuring development Year 11Spring Mock Exam week In class revision with particular focus on In class revision with particular focus on (Links to OCR B What is a landscape (natural and built) Topics 3,4,5,7 and human fieldwork practice What is meant by development? Paper 3 practice linked to topics 4,6,8 Paper 1. Paper 2 and 3. 9-1 GCSE) UK Landscapes (upland, lowland and glacial) – paper What is meant by uneven development? distribution and characteristics How can countries be classified by Use revision booklets, green revision guides Use revision booklets, green revision guides River Landscapes development?(AC’s, EDC’s, LIDC’s) CASE STUDY of a LIDC – Zambia and other strategies such as quick quizzes, and other strategies such as quick quizzes, AO1 Coastal Landscapes What geomorphic processes shape river Global distribution of AC’s, EDC’s, LIDC’s Location and background case study mind-maps, flash cards, case study mind-maps, flash cards, Geographical What geomorphic processes shape coastal landscapes? (Erosion, weathering, mass Economic, social, environmental and Current level of development knowledge organisers and use of past papers knowledge organisers and use of past Knowledge landscapes? (Types of erosion, weathering, movement, transportation and deposition) combined measures of development. -

5. Phys Landscapes Student Booklet PDF File

GCSE GEOGRAPHY Y9 2017-2020 PAPER 1 – LIVING WITH THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT SECTION C PHYSICAL LANDSCAPES IN THE UK Student Name: _____________________________________________________ Class: ___________ Specification Key Ideas: Key Idea Oxford text book UK Physical landscapes P90-91 The UK has a range of diverse landscapes Coastal landscapes in the UK P92-113 The coast is shape by a number of physical processes P92-99 Distinctive coastal landforms are the result of rock type, structure and physical P100-105 processes Different management strategies can be used to protect coastlines from the effects of P106-113 physical processes River landscapes in the UK P114-131 The shape of river valleys changes as rivers flow downstream P114-115 Distinctive fluvial (river) landforms result from different physical processes P116-123 Different management strategies can be used to protect river landscapes from the P124-131 effects of flooding Scheme of Work: Lesson Learning intention: Student booklet 1 UK landscapes & weathering P10-12 2 Weathering P12-13 3 Coastal landscapes – waves & coastal erosion P14-16 4 Coastal transport & deposition P16-17 5 Landforms of coastal erosion P17-21 6 Landforms of coastal deposition P22-24 7 INTERVENTION P24 8 Case Study: Swanage (Dorset) P24-25 9 Managing coasts – hard engineering P26-28 10 Managing coasts – soft engineering P28-30 11 Managed retreat P30-32 12 Case Study: Lyme Regis (Dorset) P32-33 13 INTERVENTION P33 14 River landscapes P34-35 15 River processes P35-36 16 River landforms P36-41 17 Case Study: -

CSHL AR 1981.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT 1981 COLD SPRING HARBOR LABORATORY Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Box 100, Cold Spring Harbor, New York 11724 1981 Annual Report Editors: Annette Kirk, Elizabeth Ritcey Photo credits: 9, 12, Elizabeth Watson; 209, Korab, Ltd.; 238, Robert Belas; 248, Ed Tronolone. All otherphotos by Herb Parsons. Front and back covers: Sammis Hall, new residence facility at the Banbury Conference Center.Photos by K orab, Ltd. COLD SPRING HARBOR LABORATORY COLD SPRING HARBOR, LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK OFFICERS OF THE CORPORATION Walter H. Page, Chairman Dr. Bayard Clarkson, Vice-Chairman Dr. Norton D. Zinder, Secretary Robert L. Cummings, Treasurer Roderick H. Cushman, Assistant Treasurer Dr. James D. Watson, Director William R. Udry, Administrative Director BOARD OF TRUSTEES Institutional Trustees Individual Trustees Albert Einstein College of Medicine John F. Carr Dr. Matthew Scharff Emilio G. Collado Robert L. Cummings Columbia University Roderick H. Cushman Dr. Charles Cantor Walter N. Frank, Jr. John P. Humes Duke Mary Lindsay Dr. Robert Webster Walter H. Page William S. Robertson Long Island Biological Association Mrs. Franz Schneider Edward Pulling Alexander C. Tomlinson Dr. James D. Watson Massachusetts Institute of Technology Dr. Boris Magasanik Honorary Trustees Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Dr. Bayard Clarkson Dr. Harry Eagle Dr. H. Bentley Glass New York University Medical Center Dr. Alexander Hollaender Dr. Claudio Basilico The Rockefeller University Dr. Norton D. Zinder State University of New York, Stony Brook Dr. Thomas E. Shenk University of Wisconsin Dr. Masayasu Nomura Wawepex Society Bache Bleeker Yale University Dr. Charles F. Stevens Officers and trustees are as of December 31, 1981 DIRECTOR'S REPORT 1981 The daily lives of scientists are much less filled now be solvable or whether we must await the re- with clever new ideas than the public must im- ception of some new facts that as yet do not exist. -

The Role of the Hydrological Factor in Habitat Dynamics Within the Fluvial Corridor of Danube

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals THE ROLE OF THE HYDROLOGICAL FACTOR IN HABITAT DYNAMICS WITHIN THE FLUVIAL CORRIDOR OF DANUBE GH. CLOŢĂ1 ABSTRACT. -The role of the hydrological factor in habitat dynamics within the fluvial corridor of Danube. This paper had explored the connections between river hydrology with its changes and habitat dynamics. The fluvial corridor integrates spatially the channel and parts of its floodplain affected by periodical flooding and could be considered as an ecological corridor because of the size of the hydrosystem. The river and its ecosystems depend on geomorphogenetic and biological function and, thus creating a inter-dependence transposed into a concept, namely the fluvial hydrosystem, proposed firstly by Roux 1982, Amoros 1987. The hydrosystem is an ecological complex system constituted of biotopes and specific biocenoses of stream waters, stagnant water bodies, semi-aquatic, terrestrial ecosystems localized in the space of floodplain modeled directly and indirectly by river’s active force. Keywords: hydrological factor, habitats dynamics, fluvial corridor, Danube 1. INTRODUCTION The fluvial corridor integrates spatially the channel and parts of its floodplain affected by periodical flooding with an extention with hydrogeomorphological discontinuities. If initial name given to the afferent area of the lower stream of river “ Le Balta du Danube” (Emm. de Martonne, 1902) and “Balta Dunării” (Gh. Murgoci 1907), were not used too much, and “ the easily flooded area of the Danube” (Gr. Antipa 1910) only persisted till 1960 when it have been replaced with the syntagm “Danube floodplain”. -

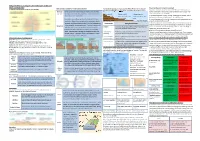

Y11 Geography

Why are there a variety of river landscapes in the UK? What is a drainage basin? Why is the flood risk in the UK increasing? An area of land drained by a river an it’s tributaries. How do river processes form distinctive landforms? How do climate, geology and slope processes affect different river landscapes? How does the long profile of a river change according to the Bradshaw model? Flooding is a natural occurrence but since 1998 severe flooding has oc- Interlock- At the source rivers have less power and flow around valley curred somewhere in the UK every year sometimes twice in a year. The ing spurs slopes (spurs) instead of eroding them. The spurs then inter- 610m above SL, 700mm rainfall Soft geology e.g. main reasons for this are as follows: 1. Increased population = more housing. Building on the cheaper land of lock from one side to the other. 2500mm rainfall Softer permeable rock mudstones, River 70m the flood plain has put 2.3million houses at risk of flooding. Hard, impermeable e.g. sandstone wide Occur where water flows over bands of rock with differing 2. Land use changes with urban developments = more impermeable surfac- resistance. Weaker less resistant rock erodes quicker due to geology e.g. shales E.g. River Severn es which increases surface run-off. increased velocity and creates a step in the river bed gradually Characteristic Changes downstream 3. Changes in weather patterns linked to climate change making extreme undercutting the more resistant rock. Continued abrasion and weather more likely as a result of the changes in the behaviour of the jet Waterfalls stream. -

2Nd Edition Geography

OXFORD IB DIPLOMA PROGRAMME 2ND EDITION GEOGRAPHY COURSE COMPANION Garrett Nagle Briony Cooke Contents Unit 1 Changing population Option A Freshwater – Drainage basins 1. Population and economic development patterns 388 1. Drainage basin hydrology and geomorphology 2 2. Changing populations and places 396 2. Flooding and flood mitigation 16 3. Challenges and opportunities 409 3. Water scarcity and water quality 28 4. Water management futures 39 Unit 2 Global climate – vulnerability Option B Oceans and coastal margins and resilience 1. The causes of global climate change 426 1. Ocean–atmosphere interactions 52 2. The consequences of global climate change 436 2. Interactions between oceans and the coastal places 65 3. Responding to climate change 451 3. Managing coastal margins 79 Unit 3 Global resource consumption 4. Ocean management futures 91 and security Option C Extreme environments 1. Global trends in consumption 469 1. The characteristics of extreme 2. Impacts of changing trends in resource environments 107 consumption 487 2. Physical processes and landscapes 116 3. Resource stewardship 504 3. Managing extreme environments 128 4. Extreme environments’ futures 143 Unit 4 Power, places and networks 1. Global interactions and global power 516 Option D Geophysical hazards 2. Global networks and flows 530 1. Geophysical systems 164 3. Human and physical influences on 2. Geophysical hazard risks 176 global interactions 552 3. Hazard risk and vulnerability 186 4. Future resilience and adaptation 196 Unit 5 Human development and diversity 1. Development opportunities 569 Option E Leisure, tourism and sport 2. Changing identities and cultures 583 1. Changing leisure patterns 213 3. Local responses to global interactions 598 2. -

Hyperspectral Remote Sensing

419 8 1 Hyperspectral Remote Sensing 2 Eyal Ben Dor, Tim Malthus, Antonio Plaza, and Daniel Schläpfer 8.1 3 Introduction 4 Hyperspectral Remote Sensing (HRS) and Imaging Spectroscopy (IS), are two 5 technologies that can provide detailed spectral information from every pixel 6 in an image. Whereas HRS refers mostly to remote sensing (from a distance), 7 the emerging IS technology covers all spatial–spectral domains, from micro- 8 scopic to macroscopic. IS capability is an innovative development of the 9 charge–coupled device (CCD), which was invented by the two 2009 Nobel 10 prize in Physics winners Willard Boyle and George Smith from Bell Labora- 11 tories in 1969. They provided the first assembly capable of generating digital 12 images. In 1972 A. Goetz realized that it was possible to use the CCD for spec- 13 tral applications and after developing the first portable spectrometer together 14 with significant improvements in the area array assembly, a combined spa- 15 tial and spectral capability was designed and successfully operated from orbit 16 (LANDSAT program). In general, HRS/IS is a technology that provides spa- 17 tial and spectral information simultaneously, improving our understanding 18 of the remote environment. It enables accurate identification of both targets 19 and phenomena as the spectral information is presented on a spatial rather 20 than point (pixel) basis. HRS/IS technology is well accepted in remote sens- 21 ing as a tool for many applications, such as in geology, ecology, geomorphol- 22 ogy, limnology, pedology, atmospheric and forensic sciences, especially for 23 cases in which other remote sensing means have failed or are incapable of ob- 24 taining additional information. -

Geography Genius – Check Me Out! Yellow I Know Some of It but Not Really Too Sure

Mrs Streeter’s COMPONENT 2 BIBLE UKs evolving physical landscape UKs evolving human landscape Geographical Investigations (Fieldwork) Traffic light sheets Key words Common questions *this booklet should be used in addition to the revision you already have planned! Contents The questions will appear in this order in your exam You need to answer all the questions in the booklet 1. UKs evolving physical landscape 2. UKs evolving human landscape 3. Geographical investigations (Fieldwork) Information about the exam Time: 1 hour 30 mins Worth: 94 marks Each topic is worth 30 marks The biggest question you will answer on each topic will be out of 8 marks One question in question 1 will also be worth an additional 4 marks for SPAG This will show as a 12 mark question but it really just means 8 for answer + 4 for SPaG Counts for: 37.5% of your final grade *Shorter questions do not need case study detail (although if you can put it in then it may carry marks) *8 or 12 mark questions MUST HAVE CASE STUDY EXAMPLES AND FACTS In section 3 you must choose to answer 2 out of 4 questions Answer: Coastal change and conflict and Dynamic urban areas The UK’s Evolving Physical Landscape review sheet: Coasts Colour code each question or statement. Green I fully understand. I’m a Geography genius – check me out! Yellow I know some of it but not really too sure. I need a bit of help/revision. Red I have no idea – I don’t understand this? Was I even here? Key statement Colour 4.1a) How Geology, past tectonic and glacial processes have made upland areas and lowland landscapes. -

What Should Schools Teach? ‘This Book Brings Profound Questions About What Children Need to Know Back to the Centre of Educational Enquiry Where They Belong

What Should Schools Teach? Schools Should What ‘This book brings profound questions about what children need to know back to the centre of educational enquiry where they belong. The additional chapters in this second edition knowledge and the curriculum are excellent. We all need to read it.’– Professor Elizabeth Rata, University of Auckland The design of school curriculums involves deep thought about the nature of knowledge and its value to learners and society. It is a serious responsibility that raises a number of questions. What is knowledge for? What knowledge is important for children to learn? How do we decide what knowledge matters in each school subject? And how far should the knowledge Edited by Alka Sehgal Cuthbert we teach in school be related to academic disciplinary knowledge? These and many other questions are taken up in What Should Schools Teach? and Alex Standish The blurring of distinctions between pedagogy and curriculum, and between experience and knowledge, has served up a confusing message for teachers about the part that each plays in the education of children. Schools teach through subjects, but there is little consensus about what constitutes a subject and what they are for. This book aims to dispel confusion through a What robust rationale for what schools should teach that offers key understanding to teachers of the relationship between knowledge (what to teach) and their own pedagogy (how to teach), and how both need to be informed by values of intellectual freedom and autonomy. Should This second edition includes new chapters on Chemistry, Drama, Music and Religious Education, and an updated chapter on Biology. -

Rivers? a Means of with Water Rivers Are Because Important They 1

RIVER LANDSCAPES 3. What work do rivers do? 4. How do rivers change from source to mouth? Rivers flow downhill due to gravity. Where the gra- Although no two rivers are the same, many share a similar long profile, 1. Why are rivers Important? dient of a river is steep, more energy is provided to which shows a change in the gradient of a river from source to mouth. erode the landscapes. Material found within a river A cross profile shows the gradient of slopes across the valley. Rivers are important because they shape the landscape, supply us is known as the load and this material is transport- with water, influence the location of settlements and provide us with ed and deposited downstream. a means of travel, power and recreation. 1. River Erosion. 2. How does water flow into rivers? There are four types of river erosion: abrasion, The water cycle is the journey water takes between the hydrosphere attrition, hydraulic action and corrosion. (see key (water), atmosphere (air) and lithosphere (land). At it’s most simple, term glossary) this involves evaporation, condensation and precipitation Geography 2. River Transport The greater the volume of water in the river, the more energy it will have to transport material. There are four different ways in which a river may transport material: suspension, solution, saltation and traction (see key term glossary) Suspension Suspension YEAR 8 YEAR www.geobytes.org.uk Traction Changes in the Valley Downstream Saltation In the upper course of a river the gradient is steeper and the valley have A drainage basin is an steep v-shaped valley sides and narrow valley floors, as it moves further downstream the valley gets flatter and much wider. -

GCSE Geography a 1GA0 03 1GA0 03

Examiners’ Report June 2018 GCSE Geography A 1GA0 03 Edexcel and BTEC Qualifications Edexcel and BTEC qualifications come from Pearson, the UK’s largest awarding body. We provide a wide range of qualifications including academic, vocational, occupational and specific programmes for employers. For further information visit our qualifications websites at www.edexcel.com or www.btec.co.uk. Alternatively, you can get in touch with us using the details on our contact us page at www.edexcel.com/contactus. Giving you insight to inform next steps ResultsPlus is Pearson’s free online service giving instant and detailed analysis of your students’ exam results. See students’ scores for every exam question. Understand how your students’ performance compares with class and national averages. Identify potential topics, skills and types of question where students may need to develop their learning further. For more information on ResultsPlus, or to log in, visit www.edexcel.com/resultsplus. Your exams officer will be able to set up your ResultsPlus account in minutes via Edexcel Online. Pearson: helping people progress, everywhere Pearson aspires to be the world’s leading learning company. Our aim is to help everyone progress in their lives through education. We believe in every kind of learning, for all kinds of people, wherever they are in the world. We’ve been involved in education for over 150 years, and by working across 70 countries, in 100 languages, we have built an international reputation for our commitment to high standards and raising achievement through innovation in education. Find out more about how we can help you and your students at: www.pearson.com/uk.