CSHL AR 1981.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Classes of Endosymbiont of Paramecium Aurelia

J. Cell Sci. 5, 65-91 (1969) 65 Printed in Great Britain THE CLASSES OF ENDOSYMBIONT OF PARAMECIUM AURELIA G. H. BEALE AND A. JURAND Institute of Animal Genetics, Edinburgh 9, Scotland AND J. R. PREER Department of Zoology, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana 47401, U.S.A. SUMMARY The endosymbionts of Paramecium aurelia appear to consist of a number of different Gram- negative bacteria which have come to live within many strains of paramecia. It is not known whether in nature this relationship is mutually beneficial or not. The symbionts from one paramecium may kill other paramecia lacking that kind of symbiont. We identify the following classes of endosymbiotic organisms. First, kappa particles (found in P. aurelia, syngens 2 and 4) ordinarily contain highly characteristic refractile, or R, bodies, which are associated with the production of a toxin which kills sensitive paramecia. In certain mutants of kappa found in the laboratory both R bodies and ability to kill have been lost. Second, mu particles (in syngens i, 2 and 8) produce the phenomenon of mate-killing. Third, lambda (syngens 4 and 8) and sigma particles (syngen 2) are very large, flagellated organisms which kill only paramecia of syngens 3, 5 and 9, and are enclosed in membrane-bound vacuoles. Fourth, gamma particles (syngen 8) are minute endosymbionts, surrounded by an additional membrane resembling endoplasmic reticulum. They have strong killing activity but no R bodies. Fifth, delta particles (syngens 1 and 6) possess a dense layer covering the outer membrane. At least one of the two known stocks is a killer. -

Geography for the IB DIPLOMA

OXFORD IB STUDY GUIDES Garrett Nagle Briony Cooke Geography FOR THE IB DIPLOMA 2nd edition OPTION A FRESHWATER – DRAINAGE BASINS 1 DRAINAGE BASIN HYDROLOGY AND GEOMORPHOLOGY The drainage basin DEFINITIONS Evaporation is the physical process by which a liquid becomes a gas. It is a function of: The drainage basin is an area that is drained by a river • vapour pressure and its tributaries. Drainage basins have inputs, stores, • air temperature processes and outputs. The inputs and outputs cross the • wind boundary of the drainage basin, hence the drainage basin • rock surface, for example, bare soils and rocks have is an open system. The main input is precipitation, which is high rates of evaporation compared with surfaces regulated by various means of storage. The outputs include which have a protective tilth where rates are low. evaporation and transpiration. Flows include infiltration, throughflow, overland flow and base flow, and stores Transpiration is the loss of water from vegetation. include vegetation, soil, aquifers and the cryosphere (snow Evapotranspiration is the combined loss of water and ice). from vegetation and water surfaces to the atmosphere. Drainage basin hydrology Potential evapotranspiration is the rate of water loss from an area if there were no shortage of water. PRECIPITATION Channel Interception precipitation 1. VEGETATION FLOWS Stemflow & throughfall Infiltration is the process by which water sinks into the Overland flow 2. SURFACE STORAGE 5. CHANNEL ground. Infiltration capacity refers to the amount of Floods moisture that a soil can hold. By contrast, the infiltration Capilliary Infiltration rise rate refers to the speed with which water can enter the Interflow 3. -

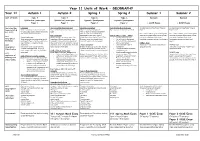

Year 11 Units of Work - GEOGRAPHY Year 11 Autumn 1 Autumn 2 Spring 1 Spring 2 Summer 1 Summer 2

Year 11 Units of Work - GEOGRAPHY Year 11 Autumn 1 Autumn 2 Spring 1 Spring 2 Summer 1 Summer 2 Unit of Work Topic 3 Topic 3 Topic 6 Topic 6 Revision Revision Distinctive Landscapes Distinctive Landscapes Dynamic Development Dynamic Development Paper 1 Paper 1 Paper 2 Paper 2 + GCSE Exams + GCSE Exams Curriculum Map Landscapes Year 11 Autumn Mock Exam week Measuring development Year 11Spring Mock Exam week In class revision with particular focus on In class revision with particular focus on (Links to OCR B What is a landscape (natural and built) Topics 3,4,5,7 and human fieldwork practice What is meant by development? Paper 3 practice linked to topics 4,6,8 Paper 1. Paper 2 and 3. 9-1 GCSE) UK Landscapes (upland, lowland and glacial) – paper What is meant by uneven development? distribution and characteristics How can countries be classified by Use revision booklets, green revision guides Use revision booklets, green revision guides River Landscapes development?(AC’s, EDC’s, LIDC’s) CASE STUDY of a LIDC – Zambia and other strategies such as quick quizzes, and other strategies such as quick quizzes, AO1 Coastal Landscapes What geomorphic processes shape river Global distribution of AC’s, EDC’s, LIDC’s Location and background case study mind-maps, flash cards, case study mind-maps, flash cards, Geographical What geomorphic processes shape coastal landscapes? (Erosion, weathering, mass Economic, social, environmental and Current level of development knowledge organisers and use of past papers knowledge organisers and use of past Knowledge landscapes? (Types of erosion, weathering, movement, transportation and deposition) combined measures of development. -

Redundancy and Specificity F Mechta-Grigoriou Et Al 2379

Oncogene (2001) 20, 2378 ± 2389 ã 2001 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950 ± 9232/01 $15.00 www.nature.com/onc The mammalian Jun proteins: redundancy and speci®city Fatima Mechta-Grigoriou1, Damien Gerald1 and Moshe Yaniv*,1 1Unite des virus oncogenes, CNRS URA 1644, Institut Pasteur, 25 rue du Docteur Roux, 75724 Paris Cedex 15, France The AP-1 transcription factor is composed of a mixture transcription factors. These proteins are characterized of homo- and hetero-dimers formed between Jun and Fos by a highly charged, basic DNA binding domain, proteins. The dierent Jun and Fos family members vary immediately adjacent to an amphipathic dimerization signi®cantly in their relative abundance and their domain, referred as the `Leucine zipper' (Kouzarides interactions with additional proteins generating a and Zi, 1988; Landschulz et al., 1988). Dimerization complex network of transcriptional regulators. Thus, is required for speci®c and high anity binding to the the functional activity of AP-1 in any given cell depends palindromic DNA sequence, TGAC/GTCA (Rauscher on the relative amount of speci®c Jun/Fos proteins which et al., 1988; Gentz et al., 1989; Hirai and Yaniv, 1989; are expressed, as well as other potential interacting Ransone et al., 1989; Schuermann et al., 1989; Turner proteins. This diversity of AP-1 components has and Tjian, 1989). The dierent AP-1 dimers exhibit complicated our understanding of AP-1 function and similar DNA binding speci®cities but dier in their resulted in a paucity of information about the precise transactivation eciencies (Chiu et al., 1989; Hirai et role of individual AP-1 members in distinct cellular al., 1990; Kerppola and Curran, 1991b; Suzuki et al., processes. -

Does River Restoration Work? Taxonomic and Functional Trajectories at Two Restoration Schemes

Science of the Total Environment 618 (2018) 961–970 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv Does river restoration work? Taxonomic and functional trajectories at two restoration schemes Judy England a,⁎, Martin Anthony Wilkes b a Environment Agency, Red Kite House, Howbery Park, Crowmarsh Gifford, Wallingford OX10 8BD, United Kingdom b Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience, Coventry University, Ryton Gardens, Wolston Lane, Ryton-on-Dunsmore, Coventry CV8 3LG, United Kingdom HIGHLIGHTS GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT • Restoration of natural process was the aim of two river restoration case studies. • The projects restored physical habitat composition. • Rehabilitation of macroinvertebrate structural complexity was limited. • Restoration of functional integrity was more difficult to achieve. • Functional traits are useful in evaluating river restoration projects. article info abstract Article history: Rivers and their floodplains have been severely degraded with increasing global activity and expenditure under- Received 27 April 2017 taken on restoration measures to address the degradation. Early restoration schemes focused on habitat creation Received in revised form 1 September 2017 with mixed ecological success. Part of the lack of ecological success can be attributed to the lack of effective mon- Accepted 2 September 2017 itoring. The current focus of river restoration practice is the restoration of physical processes and functioning of Available online 7 November 2017 systems. The ecological assessment of restoration schemes may need to follow the same approach and consider whether schemes restore functional diversity in addition to taxonomic diversity. This paper examines whether Keywords: River restoration two restoration schemes, on lowland UK rivers, restored macroinvertebrate taxonomic and functional (trait) di- Process based restoration versity and relates the findings to the Bradshaw's model of ecological restoration. -

5. Phys Landscapes Student Booklet PDF File

GCSE GEOGRAPHY Y9 2017-2020 PAPER 1 – LIVING WITH THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT SECTION C PHYSICAL LANDSCAPES IN THE UK Student Name: _____________________________________________________ Class: ___________ Specification Key Ideas: Key Idea Oxford text book UK Physical landscapes P90-91 The UK has a range of diverse landscapes Coastal landscapes in the UK P92-113 The coast is shape by a number of physical processes P92-99 Distinctive coastal landforms are the result of rock type, structure and physical P100-105 processes Different management strategies can be used to protect coastlines from the effects of P106-113 physical processes River landscapes in the UK P114-131 The shape of river valleys changes as rivers flow downstream P114-115 Distinctive fluvial (river) landforms result from different physical processes P116-123 Different management strategies can be used to protect river landscapes from the P124-131 effects of flooding Scheme of Work: Lesson Learning intention: Student booklet 1 UK landscapes & weathering P10-12 2 Weathering P12-13 3 Coastal landscapes – waves & coastal erosion P14-16 4 Coastal transport & deposition P16-17 5 Landforms of coastal erosion P17-21 6 Landforms of coastal deposition P22-24 7 INTERVENTION P24 8 Case Study: Swanage (Dorset) P24-25 9 Managing coasts – hard engineering P26-28 10 Managing coasts – soft engineering P28-30 11 Managed retreat P30-32 12 Case Study: Lyme Regis (Dorset) P32-33 13 INTERVENTION P33 14 River landscapes P34-35 15 River processes P35-36 16 River landforms P36-41 17 Case Study: -

Journal of Molecular Biology

JOURNAL OF MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Audience p.2 • Impact Factor p.2 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.6 ISSN: 0022-2836 DESCRIPTION . Journal of Molecular Biology (JMB) provides high quality, comprehensive and broad coverage in all areas of molecular biology. The journal publishes original scientific research papers that provide mechanistic and functional insights and report a significant advance to the field. The journal encourages the submission of multidisciplinary studies that use complementary experimental and computational approaches to address challenging biological questions. Research areas include but are not limited to: Biomolecular interactions, signaling networks, systems biology Cell cycle, cell growth, cell differentiation Cell death, autophagy Cell signaling and regulation Chemical biology Computational biology, in combination with experimental studies DNA replication, repair, and recombination Development, regenerative biology, mechanistic and functional studies of stem cells Epigenetics, chromatin structure and function Gene expression Receptors, channels, and transporters Membrane processes Cell surface proteins and cell adhesion Methodological advances, both experimental and theoretical, including databases Microbiology, virology, and interactions with the host or environment Microbiota mechanistic and functional studies Nuclear organization Post-translational modifications, proteomics Processing and function of biologically -

The Role of the Hydrological Factor in Habitat Dynamics Within the Fluvial Corridor of Danube

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals THE ROLE OF THE HYDROLOGICAL FACTOR IN HABITAT DYNAMICS WITHIN THE FLUVIAL CORRIDOR OF DANUBE GH. CLOŢĂ1 ABSTRACT. -The role of the hydrological factor in habitat dynamics within the fluvial corridor of Danube. This paper had explored the connections between river hydrology with its changes and habitat dynamics. The fluvial corridor integrates spatially the channel and parts of its floodplain affected by periodical flooding and could be considered as an ecological corridor because of the size of the hydrosystem. The river and its ecosystems depend on geomorphogenetic and biological function and, thus creating a inter-dependence transposed into a concept, namely the fluvial hydrosystem, proposed firstly by Roux 1982, Amoros 1987. The hydrosystem is an ecological complex system constituted of biotopes and specific biocenoses of stream waters, stagnant water bodies, semi-aquatic, terrestrial ecosystems localized in the space of floodplain modeled directly and indirectly by river’s active force. Keywords: hydrological factor, habitats dynamics, fluvial corridor, Danube 1. INTRODUCTION The fluvial corridor integrates spatially the channel and parts of its floodplain affected by periodical flooding with an extention with hydrogeomorphological discontinuities. If initial name given to the afferent area of the lower stream of river “ Le Balta du Danube” (Emm. de Martonne, 1902) and “Balta Dunării” (Gh. Murgoci 1907), were not used too much, and “ the easily flooded area of the Danube” (Gr. Antipa 1910) only persisted till 1960 when it have been replaced with the syntagm “Danube floodplain”. -

Data on the Occurrence of Species of the Paramecium Aurelia Complex World-Wide

Protistology 1 (4), 179–184 (2000) Protistology August, 2000 Data on the occurrence of species of the Paramecium aurelia complex world-wide Ewa Przybo and Sergei Fokin1 Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals, Polish Academy of Sciences, Kraków, Poland, 1 Biological Research Institute of St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia Summary At present 15 species of the Paramecium aurelia complex are known world-wide (Sonneborn, 1975; Aufderheide et al., 1983). Data on their distribution in the Americas, Africa, and Australia are mainly in the papers cited above, the following ones are cosmopolitan: P. primaurelia, P. biaurelia, P. tetraurelia, and P. sexaurelia. Data on the distribution of species of the P. aurelia complex in Asia are scattered in the literature and rather rare, P. primaurelia, P. biaurelia, P. tetraurelia, P. sexaurelia, and P. novaurelia were there recorded. The greatest data on distribution and frequency of occurrence of the particular species of the P. aurelia complex concerns Europe. As far as Europe is concerned, the following conclusions were drawn: P. novaurelia is a dominant species (found in 178 habitats among 459 studied), P. biaurelia is a frequent one (in 151 habitats), while P. primaurelia (in 103 habitats) is also characteristic but less frequent. Other species known from Europe are rare. Key words: frequency of species occurrence, geographical distribution, Paramecium aurelia spp. complex At present 15 species of the P. aurelia complex are occurrence of the particular species of the P. aurelia com- known world-wide (Sonneborn,1975; Aufderheide et al., plex concerns Europe (Table 3). The following species 1983). have been recorded there: P. -

Factors Determining the Frequency of the Killer Trait Within Populations of the Paramecium Aurelia Complex

Copyright 0 1987 by the Genetics Society of America Factors Determining the Frequency of the Killer Trait Within Populations of the Paramecium aurelia Complex Wayne G. Landis Environmental Toxicology Branch, Toxicology Division, Chemical Research and Development Center, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland, 21010-5423 Manuscript received March 3, 1986 Revised copy accepted September 15, 1986 ABSTRACT The factors maintaining the cytoplasmically inherited killer trait in populations of Paramecium tetraurelia and Paramecium biaurelia were examined using, in part, computer simulation. Frequency of the K and k alleles, infection and loss of the endosymbionts,recombination during conjugation and autogamy, cytoplasmic exchange and natural selection were incorporated in a model. Infection during cytoplasmic exchange at conjugation and natural selection were factors that would increase the proportion of killers in a population. Conversely, k alleles reduced the proportion of killers in a population,acting through conjugation and autogamy. Field studies indicate that the odd mating type is prevalent in P. tetraurelia isolated from nature. Conjugation and therefore transmission by cyto- plasmic transfer would be rare. Competition studies indicate a strong selective disadvantage for sensitives at concentrationsfound in nature. Natural selection must therefore be the factor maintaining the killer trait in P. tetraurelia. YTOPLASMIC inheritance is a widespread phe- The two hosts, P. tetraurelia and P. biaurelia, are C nomenon that includes sex and drug resistance sibling species within the P. aurelia complex as con- in bacteria, CO2 sensitivity in Drosophilia melanogaster structed by SONNEBORN(1975). Paramecia of this and possibly certain tumors in mammals. Indeed, the complex undergo two major sexual processes, conju- origin of the eukaryotic cell may have been dependent gation and autogamy. -

The Culture of Paramecium a Ureliain the Absence

VOL. 35, 1949 ZOOLOGY: VAN WAGTENDONK AND HACKETT 155 6 See, for example, top of page 9, J. of Symbolic Logic, 6. 7Compare middle of page 158, Ibid., 7. 8 Am. Math. Mo., 44, p. 70. 9 J. of Symbolic Logic, 7, p. 1. The inconisistent system contains N7' in place of N7. However, whether the replacement of N7' by N7 would affect the derivation of the Burali-Forti contradiction is not immediately obvious. 10 Middle of page 228, J. r. angew. Math., 160. 11 If we want to obtain N7' instead of N7, just delete the clause "and all the bound variables in 4 are small variables" in ZZ7. 1 Compare the proof of *231, ML, page 171. 13 Ti can be proved by ZZI and ZZ1 in the usual manner. Cf., e.g., ML, page 170, *223. * I am indebted to Dr. I. L. Novak for suggestion in connection with the introduction of large variables. I wish also to thank Dr. Novak and Dr. H. Hiz for reading the manuscript of the paper and suggesting improvements in the manner of presentation. I am grateful to Professor Quine for corrections. THE CULTURE OF PARAMECIUM A URELIA IN THE ABSENCE OF OTHER LIVING ORGANISMS BY W. J. VAN WAGTENDONK AND PATRICIA L. HACKETT DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY, INDIANA UNIVERSITY, BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA Communicated by T. M. Sonneborn, January 22, 1949 The growth requirements of ciliated protozoa are very complex, and little accurate work on this has so far been possible since only a few species have been cultivated in the absence of other living organisms. -

Paramecium Diversity and a New Member of the Paramecium Aurelia Species Complex Described from Mexico

diversity Article Paramecium Diversity and a New Member of the Paramecium aurelia Species Complex Described from Mexico Alexey Potekhin 1,2,* and Rosaura Mayén-Estrada 3 1 Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Biology, Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia 2 Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Protistology, Zoological Institute RAS, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia 3 Laboratorio de Protozoología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Circuito Ext. s/núm. Ciudad Universitaria, Av. Universidad 3000, Coyoacán, 04510 Ciudad de México, Mexico; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:B5A24294-3165-40DA-A425-3AD2D47EB8E7 Received: 17 April 2020; Accepted: 13 May 2020; Published: 15 May 2020 Abstract: Paramecium (Ciliophora) is an ideal model organism to study the biogeography of protists. However, many regions of the world, such as Central America, are still neglected in understanding Paramecium diversity. We combined morphological and molecular approaches to identify paramecia isolated from more than 130 samples collected from different waterbodies in several states of Mexico. We found representatives of six Paramecium morphospecies, including the rare species Paramecium jenningsi, and Paramecium putrinum, which is the first report of this species in tropical regions. We also retrieved five species of the Paramecium aurelia complex, and describe one new member of the complex, Paramecium quindecaurelia n. sp., which appears to be a sister species of Paramecium biaurelia. We discuss criteria currently applied for differentiating between sibling species in Paramecium. Additionally, we detected diverse bacterial symbionts in some of the collected ciliates. Keywords: biogeography; ciliates; Paramecium quindecaurelia; cytochrome C oxidase subunit I gene; sibling species; species concept in protists; bacterial symbionts 1.