River Processes and Landscape Revision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geography for the IB DIPLOMA

OXFORD IB STUDY GUIDES Garrett Nagle Briony Cooke Geography FOR THE IB DIPLOMA 2nd edition OPTION A FRESHWATER – DRAINAGE BASINS 1 DRAINAGE BASIN HYDROLOGY AND GEOMORPHOLOGY The drainage basin DEFINITIONS Evaporation is the physical process by which a liquid becomes a gas. It is a function of: The drainage basin is an area that is drained by a river • vapour pressure and its tributaries. Drainage basins have inputs, stores, • air temperature processes and outputs. The inputs and outputs cross the • wind boundary of the drainage basin, hence the drainage basin • rock surface, for example, bare soils and rocks have is an open system. The main input is precipitation, which is high rates of evaporation compared with surfaces regulated by various means of storage. The outputs include which have a protective tilth where rates are low. evaporation and transpiration. Flows include infiltration, throughflow, overland flow and base flow, and stores Transpiration is the loss of water from vegetation. include vegetation, soil, aquifers and the cryosphere (snow Evapotranspiration is the combined loss of water and ice). from vegetation and water surfaces to the atmosphere. Drainage basin hydrology Potential evapotranspiration is the rate of water loss from an area if there were no shortage of water. PRECIPITATION Channel Interception precipitation 1. VEGETATION FLOWS Stemflow & throughfall Infiltration is the process by which water sinks into the Overland flow 2. SURFACE STORAGE 5. CHANNEL ground. Infiltration capacity refers to the amount of Floods moisture that a soil can hold. By contrast, the infiltration Capilliary Infiltration rise rate refers to the speed with which water can enter the Interflow 3. -

River Incision Into Bedrock: Mechanics and Relative Efficacy of Plucking, Abrasion and Cavitation

River incision into bedrock: Mechanics and relative efficacy of plucking, abrasion and cavitation Kelin X. Whipple* Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Gregory S. Hancock Department of Geology, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia 23187 Robert S. Anderson Department of Earth Sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz, California 95064 ABSTRACT long term (Howard et al., 1994). These conditions are commonly met in Improved formulation of bedrock erosion laws requires knowledge mountainous and tectonically active landscapes, and bedrock channels are of the actual processes operative at the bed. We present qualitative field known to dominate steeplands drainage networks (e.g., Wohl, 1993; Mont- evidence from a wide range of settings that the relative efficacy of the gomery et al., 1996; Hovius et al., 1997). As the three-dimensional structure various processes of fluvial erosion (e.g., plucking, abrasion, cavitation, of drainage networks sets much of the form of terrestrial landscapes, it is solution) is a strong function of substrate lithology, and that joint spac- clear that a deep appreciation of mountainous landscapes requires knowl- ing, fractures, and bedding planes exert the most direct control. The edge of the controls on bedrock channel morphology. Moreover, bedrock relative importance of the various processes and the nature of the in- channels play a critical role in the dynamic evolution of mountainous land- terplay between them are inferred from detailed observations of the scapes (Anderson, 1994; Anderson et al., 1994; Howard et al., 1994; Tucker morphology of erosional forms on channel bed and banks, and their and Slingerland, 1996; Sklar and Dietrich, 1998; Whipple and Tucker, spatial distributions. -

STREAMS and RUNNING WATER Hydrologic Cycle •What Happens to Precipitation STREAM •River, Creek, Etc

STREAMS AND RUNNING WATER Hydrologic Cycle •What happens to precipitation STREAM •River, Creek, etc. • Banks, Bed • Confined to a channel –Except in time of flood •Floodplain •Longtitudinal Profile Headwaters, mouth Cross-profile V-shaped SHEETWASH –Unchanneled, thin sheet of flowing water – Results in Sheet Erosion Drainage Basin •Tributary • Divide • Examples: –Mississippi River – Amazon River Drainage Patterns •As seen from above • Dendritic (most common) • Radial • Trellis- in tilted or folded layered rock Factors affecting stream erosion and deposition •Velocity- –Distribution in cross-section •Gradient –Usually decreases downstream – Effect on deposition and erosion •Channel shape and roughness • Discharge- –Volume of water moving past a place in time •Usually given as cubic feet per second (cfs) –Usually increases downstream •Discharge- –Volume of water moving past a place in time •Usually given as cubic feet per second (cfs) –Usually increases downstream American River Discharge •In Sacramento: • Average 3,741 c.f.s. • Usual Range: –Winter 9,000 cfs – Last drought 250 cfs •1986 flood 130,000 cfs Stream Erosion •Hydraulic action • Solution- Dissolves rock • Abrasion (by sand and gravel) –Potholes •Deepens valley by eroding river bed • Lateral erosion of banks on outside of curves Transportation of Sediment •Bed load • Suspended load • Dissolved load Deposition •Bars- –moved in floods – deposited as water slows – Placer Deposits (gold, etc.) – Braided Streams •heavy load of sand and gravel • commonly from glacier outwash streams -

River Processes- Erosion, Transportation and Deposition Task 1: for Each of the Processes of Erosion and Transportation Draw a Diagram Show the Process at Work

River Processes- Erosion, Transportation and Deposition Task 1: For each of the processes of erosion and transportation draw a diagram show the process at work In the upper course of the main process is Erosion. This is where the bed and banks of the river are worn away. A river can erode in one of four ways: Process Definition Diagram Hydraulic the sheer force of water hitting the action banks of the river: Abrasion fine material rubs against the riverbank The bank is worn away by a sand- papering action called abrasion, and collapses. This occurs on the outside of meanders. Attrition material is moved along the bed of a river, collides with other material, and breaks up into smaller pieces. Corrosion rocks forming the banks and bed of a river are dissolved by acids in the water. Once the material is eroded it can then be transported by one of four ways, which will depend upon the energy of the river: Process Definition Diagram Traction large rocks and boulders are rolled along the bed of the river. Saltation smaller stones are bounced along the bed of the river Suspension fine material which is carried by the water and which gives the river its 'muddy' colour. Solution dissolved material transported by the river. In the middle and lower course, the land is much flatter, this means that the river is flowing more slowly and has much less energy. The river starts to deposit (drop) the material that it has been carry Deposition Challenge: Add labels onto the diagram to show where all of the processes could be happening in the river channel. -

Experiments on Patterns of Alluvial Cover and Bedrock Erosion in a Meandering Channel Roberto Fernández1, Gary Parker1,2, Colin P

Earth Surf. Dynam. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-2019-8 Manuscript under review for journal Earth Surf. Dynam. Discussion started: 27 February 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. Experiments on patterns of alluvial cover and bedrock erosion in a meandering channel Roberto Fernández1, Gary Parker1,2, Colin P. Stark3 1Ven Te Chow Hydrosystems Laboratory, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Illinois at 5 Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA 2Department of Geology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA 3Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, NY 10964, USA Correspondence to: Roberto Fernández ([email protected]) Abstract. 10 In bedrock rivers, erosion by abrasion is driven by sediment particles that strike bare bedrock while traveling downstream with the flow. If the sediment particles settle and form an alluvial cover, this mode of erosion is impeded by the protection offered by the grains themselves. Channel erosion by abrasion is therefore related to the amount and pattern of alluvial cover, which are functions of sediment load and hydraulic conditions, and which in turn are functions of channel geometry, slope and sinuosity. This study presents the results of alluvial cover experiments conducted in a meandering channel flume of high fixed 15 sinuosity. Maps of quasi-instantaneous alluvial cover were generated from time-lapse imaging of flows under a range of below- capacity bedload conditions. These maps were used to infer patterns -

COLD-BASED GLACIERS in the WESTERN DRY VALLEYS of ANTARCTICA: TERRESTRIAL LANDFORMS and MARTIAN ANALOGS: David R

Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIV (2003) 1245.pdf COLD-BASED GLACIERS IN THE WESTERN DRY VALLEYS OF ANTARCTICA: TERRESTRIAL LANDFORMS AND MARTIAN ANALOGS: David R. Marchant1 and James W. Head2, 1Department of Earth Sciences, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215 [email protected], 2Department of Geological Sciences, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912 Introduction: Basal-ice and surface-ice temperatures are contacts and undisturbed underlying strata are hallmarks of cold- key parameters governing the style of glacial erosion and based glacier deposits [11]. deposition. Temperate glaciers contain basal ice at the pressure- Drop moraines: The term drop moraine is used here to melting point (wet-based) and commonly exhibit extensive areas describe debris ridges that form as supra- and englacial particles of surface melting. Such conditions foster basal plucking and are dropped passively at margins of cold-based glaciers (Fig. 1a abrasion, as well as deposition of thick matrix-supported drift and 1b). Commonly clast supported, the debris is angular and sheets, moraines, and glacio-fluvial outwash. Polar glaciers devoid of fine-grained sediment associated with glacial abrasion include those in which the basal ice remains below the pressure- [10, 12]. In the Dry Valleys, such moraines may be cored by melting point (cold-based) and, in extreme cases like those in glacier ice, owing to the insulating effect of the debris on the the western Dry Valleys region of Antarctica, lack surface underlying glacier. Where cored by ice, moraine crests can melting zones. These conditions inhibit significant glacial exceed the angle of repose. In plan view, drop moraines closely erosion and deposition. -

Avulsion Dynamics in a River with Alternating Bedrock and Alluvial Reaches, Huron River, Northern Ohio (USA)

Open Journal of Modern Hydrology, 2019, 9, 20-39 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojmh ISSN Online: 2163-0496 ISSN Print: 2163-0461 Avulsion Dynamics in a River with Alternating Bedrock and Alluvial Reaches, Huron River, Northern Ohio (USA) Mark J. Potucek1,2, James E. Evans1 1Department of Geology, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH, USA 2Arizona Department of Water Resources, Phoenix, AZ, USA How to cite this paper: Potucek, M.J. and Abstract Evans, J.E. (2019) Avulsion Dynamics in a River with Alternating Bedrock and Alluvi- The Huron River consists of alternating bedrock reaches and alluvial reaches. al Reaches, Huron River, Northern Ohio Analysis of historical aerial photography from 1950-2015 reveals six major (USA). Open Journal of Modern Hydrolo- gy, 9, 20-39. channel avulsion events in the 8-km study area. These avulsions occurred in https://doi.org/10.4236/ojmh.2019.91002 the alluvial reaches but were strongly influenced by the properties of the up- stream bedrock reach (“inherited characteristics”). The bedrock reaches Received: December 19, 2018 Accepted: January 20, 2019 aligned with the azimuth of joint sets in the underlying bedrock. One inhe- Published: January 23, 2019 rited characteristic in the alluvial reach downstream is that the avulsion channels diverged only slightly from the orientation of the upstream bedrock Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and channel (range 2˚ - 38˚, mean and standard deviation 12.1˚ ± 13.7˚). A Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative second inherited characteristic is that avulsion channels were initiated from Commons Attribution International short distances downstream after exiting the upstream bedrock channel reach License (CC BY 4.0). -

The Effects of Longitudinal Differences in Gravel Mobility on the Downstream Fining Pattern in the Cosumnes River, California

The Effects of Longitudinal Differences in Gravel Mobility on the Downstream Fining Pattern in the Cosumnes River, California Candice R. Constantine,1 Jeffrey F. Mount, and Joan L. Florsheim Department of Geological Sciences, University of California, Davis, California 95616, U.S.A. (e-mail: [email protected]) ABSTRACT Downstream fining in the Cosumnes River is partially controlled by longitudinal variation in sediment mobility linked to changes in cross-sectional morphology. Strong fining occurs where the channel is self-formed with section- averaged bankfull dimensionless shear stress (t∗ ) near the threshold of motion (ca. 0.031), allowing for size-selective transport. In contrast, fining is minimal in confined reaches wheret∗ is generally greater than twice the threshold value and transport is nonselective. Downstream fining is best described by a model that depicts fining in discrete intervals separated by a segment in which equal mobility of bed material accounts for the lack of diminishing grain size. Introduction Reduction in the size of bed material with distance 1980; Rice and Church 1998; Rice 1999) or anthro- downstream is commonly observed in gravel-bed pogenic channel modifications (Surian 2002). rivers. Researchers have attributed this feature, The relative importance of sorting and abrasion termed “downstream fining,” to the processes of in determining the diminution coefficient depends selective sorting (Ashworth and Ferguson 1989; on the system in question, particularly on the na- Ferguson and Ashworth 1991; Paola et al. 1992; Fer- ture of material in transport (Bradley 1970; Parker guson et al. 1996; Seal et al. 1997) and abrasion 1991; Werrity 1992; Kodama 1994a, 1994b) and (Bradley 1970; Schumm and Stevens 1973; Werrity whether sediment discharge is limited by transport 1992; Kodama 1994a, 1994b). -

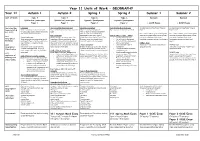

Year 11 Units of Work - GEOGRAPHY Year 11 Autumn 1 Autumn 2 Spring 1 Spring 2 Summer 1 Summer 2

Year 11 Units of Work - GEOGRAPHY Year 11 Autumn 1 Autumn 2 Spring 1 Spring 2 Summer 1 Summer 2 Unit of Work Topic 3 Topic 3 Topic 6 Topic 6 Revision Revision Distinctive Landscapes Distinctive Landscapes Dynamic Development Dynamic Development Paper 1 Paper 1 Paper 2 Paper 2 + GCSE Exams + GCSE Exams Curriculum Map Landscapes Year 11 Autumn Mock Exam week Measuring development Year 11Spring Mock Exam week In class revision with particular focus on In class revision with particular focus on (Links to OCR B What is a landscape (natural and built) Topics 3,4,5,7 and human fieldwork practice What is meant by development? Paper 3 practice linked to topics 4,6,8 Paper 1. Paper 2 and 3. 9-1 GCSE) UK Landscapes (upland, lowland and glacial) – paper What is meant by uneven development? distribution and characteristics How can countries be classified by Use revision booklets, green revision guides Use revision booklets, green revision guides River Landscapes development?(AC’s, EDC’s, LIDC’s) CASE STUDY of a LIDC – Zambia and other strategies such as quick quizzes, and other strategies such as quick quizzes, AO1 Coastal Landscapes What geomorphic processes shape river Global distribution of AC’s, EDC’s, LIDC’s Location and background case study mind-maps, flash cards, case study mind-maps, flash cards, Geographical What geomorphic processes shape coastal landscapes? (Erosion, weathering, mass Economic, social, environmental and Current level of development knowledge organisers and use of past papers knowledge organisers and use of past Knowledge landscapes? (Types of erosion, weathering, movement, transportation and deposition) combined measures of development. -

Does River Restoration Work? Taxonomic and Functional Trajectories at Two Restoration Schemes

Science of the Total Environment 618 (2018) 961–970 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv Does river restoration work? Taxonomic and functional trajectories at two restoration schemes Judy England a,⁎, Martin Anthony Wilkes b a Environment Agency, Red Kite House, Howbery Park, Crowmarsh Gifford, Wallingford OX10 8BD, United Kingdom b Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience, Coventry University, Ryton Gardens, Wolston Lane, Ryton-on-Dunsmore, Coventry CV8 3LG, United Kingdom HIGHLIGHTS GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT • Restoration of natural process was the aim of two river restoration case studies. • The projects restored physical habitat composition. • Rehabilitation of macroinvertebrate structural complexity was limited. • Restoration of functional integrity was more difficult to achieve. • Functional traits are useful in evaluating river restoration projects. article info abstract Article history: Rivers and their floodplains have been severely degraded with increasing global activity and expenditure under- Received 27 April 2017 taken on restoration measures to address the degradation. Early restoration schemes focused on habitat creation Received in revised form 1 September 2017 with mixed ecological success. Part of the lack of ecological success can be attributed to the lack of effective mon- Accepted 2 September 2017 itoring. The current focus of river restoration practice is the restoration of physical processes and functioning of Available online 7 November 2017 systems. The ecological assessment of restoration schemes may need to follow the same approach and consider whether schemes restore functional diversity in addition to taxonomic diversity. This paper examines whether Keywords: River restoration two restoration schemes, on lowland UK rivers, restored macroinvertebrate taxonomic and functional (trait) di- Process based restoration versity and relates the findings to the Bradshaw's model of ecological restoration. -

5. Phys Landscapes Student Booklet PDF File

GCSE GEOGRAPHY Y9 2017-2020 PAPER 1 – LIVING WITH THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT SECTION C PHYSICAL LANDSCAPES IN THE UK Student Name: _____________________________________________________ Class: ___________ Specification Key Ideas: Key Idea Oxford text book UK Physical landscapes P90-91 The UK has a range of diverse landscapes Coastal landscapes in the UK P92-113 The coast is shape by a number of physical processes P92-99 Distinctive coastal landforms are the result of rock type, structure and physical P100-105 processes Different management strategies can be used to protect coastlines from the effects of P106-113 physical processes River landscapes in the UK P114-131 The shape of river valleys changes as rivers flow downstream P114-115 Distinctive fluvial (river) landforms result from different physical processes P116-123 Different management strategies can be used to protect river landscapes from the P124-131 effects of flooding Scheme of Work: Lesson Learning intention: Student booklet 1 UK landscapes & weathering P10-12 2 Weathering P12-13 3 Coastal landscapes – waves & coastal erosion P14-16 4 Coastal transport & deposition P16-17 5 Landforms of coastal erosion P17-21 6 Landforms of coastal deposition P22-24 7 INTERVENTION P24 8 Case Study: Swanage (Dorset) P24-25 9 Managing coasts – hard engineering P26-28 10 Managing coasts – soft engineering P28-30 11 Managed retreat P30-32 12 Case Study: Lyme Regis (Dorset) P32-33 13 INTERVENTION P33 14 River landscapes P34-35 15 River processes P35-36 16 River landforms P36-41 17 Case Study: -

Organic Matter Decomposition and Ecosystem Metabolism As Tools to Assess the Functional Integrity of Streams and Rivers–A Systematic Review

water Review Organic Matter Decomposition and Ecosystem Metabolism as Tools to Assess the Functional Integrity of Streams and Rivers–A Systematic Review Verónica Ferreira 1,* , Arturo Elosegi 2 , Scott D. Tiegs 3 , Daniel von Schiller 4 and Roger Young 5 1 Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre–MARE, Department of Life Sciences, University of Coimbra, 3000–456 Coimbra, Portugal 2 Faculty of Science and Technology, University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), P.O. Box 644, 48080 Bilbao, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Biological Sciences, Oakland University, Rochester, MI 48309, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Evolutionary Biology, Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Institut de Recerca de l’Aigua (IdRA), University of Barcelona, Diagonal 643, 08028 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 5 Cawthron Institute, Private Bag 2, Nelson 7042, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 4 November 2020; Accepted: 8 December 2020; Published: 15 December 2020 Abstract: Streams and rivers provide important services to humans, and therefore, their ecological integrity should be a societal goal. Although ecological integrity encompasses structural and functional integrity, stream bioassessment rarely considers ecosystem functioning. Organic matter decomposition and ecosystem metabolism are prime candidate indicators of stream functional integrity, and here we review each of these functions, the methods used for their determination, and their strengths and limitations for bioassessment. We also provide a systematic review of studies that have addressed organic matter decomposition (88 studies) and ecosystem metabolism (50 studies) for stream bioassessment since the year 2000. Most studies were conducted in temperate regions. Bioassessment based on organic matter decomposition mostly used leaf litter in coarse-mesh bags, but fine-mesh bags were also common, and cotton strips and wood were frequent in New Zealand.