General Chemistry II Chapter 18 Lecture Notes Entropy, Free Energy and Equilibrium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 3. Second and Third Law of Thermodynamics

Chapter 3. Second and third law of thermodynamics Important Concepts Review Entropy; Gibbs Free Energy • Entropy (S) – definitions Law of Corresponding States (ch 1 notes) • Entropy changes in reversible and Reduced pressure, temperatures, volumes irreversible processes • Entropy of mixing of ideal gases • 2nd law of thermodynamics • 3rd law of thermodynamics Math • Free energy Numerical integration by computer • Maxwell relations (Trapezoidal integration • Dependence of free energy on P, V, T https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trapezoidal_rule) • Thermodynamic functions of mixtures Properties of partial differential equations • Partial molar quantities and chemical Rules for inequalities potential Major Concept Review • Adiabats vs. isotherms p1V1 p2V2 • Sign convention for work and heat w done on c=C /R vm system, q supplied to system : + p1V1 p2V2 =Cp/CV w done by system, q removed from system : c c V1T1 V2T2 - • Joule-Thomson expansion (DH=0); • State variables depend on final & initial state; not Joule-Thomson coefficient, inversion path. temperature • Reversible change occurs in series of equilibrium V states T TT V P p • Adiabatic q = 0; Isothermal DT = 0 H CP • Equations of state for enthalpy, H and internal • Formation reaction; enthalpies of energy, U reaction, Hess’s Law; other changes D rxn H iD f Hi i T D rxn H Drxn Href DrxnCpdT Tref • Calorimetry Spontaneous and Nonspontaneous Changes First Law: when one form of energy is converted to another, the total energy in universe is conserved. • Does not give any other restriction on a process • But many processes have a natural direction Examples • gas expands into a vacuum; not the reverse • can burn paper; can't unburn paper • heat never flows spontaneously from cold to hot These changes are called nonspontaneous changes. -

Organocatalytic Asymmetric N-Sulfonyl Amide C-N Bond Activation to Access Axially Chiral Biaryl Amino Acids

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14799-8 OPEN Organocatalytic asymmetric N-sulfonyl amide C-N bond activation to access axially chiral biaryl amino acids Guanjie Wang1, Qianqian Shi2, Wanyao Hu1, Tao Chen1, Yingying Guo1, Zhouli Hu1, Minghua Gong1, ✉ ✉ ✉ Jingcheng Guo1, Donghui Wei 2 , Zhenqian Fu 1,3 & Wei Huang1,3 1234567890():,; Amides are among the most fundamental functional groups and essential structural units, widely used in chemistry, biochemistry and material science. Amide synthesis and trans- formations is a topic of continuous interest in organic chemistry. However, direct catalytic asymmetric activation of amide C-N bonds still remains a long-standing challenge due to high stability of amide linkages. Herein, we describe an organocatalytic asymmetric amide C-N bonds cleavage of N-sulfonyl biaryl lactams under mild conditions, developing a general and practical method for atroposelective construction of axially chiral biaryl amino acids. A structurally diverse set of axially chiral biaryl amino acids are obtained in high yields with excellent enantioselectivities. Moreover, a variety of axially chiral unsymmetrical biaryl organocatalysts are efficiently constructed from the resulting axially chiral biaryl amino acids by our present strategy, and show competitive outcomes in asymmetric reactions. 1 Key Laboratory of Flexible Electronics & Institute of Advanced Materials, Jiangsu National Synergetic Innovation Center for Advanced Materials, Nanjing Tech University, 30 South Puzhu Road, Nanjing 211816, China. 2 College -

Reliable Determination of Amidicity in Acyclic Amides and Lactams Stephen A

Article pubs.acs.org/joc Reliable Determination of Amidicity in Acyclic Amides and Lactams Stephen A. Glover* and Adam A. Rosser Department of Chemistry, School of Science and Technology, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: Two independent computational methods have been used for determination of amide resonance stabilization and amidicities relative to N,N-dimethylacetamide for a wide range of acyclic and cyclic amides. The first method utilizes carbonyl substitution nitrogen atom replacement (COSNAR). The second, new approach involves determination of the difference in amide resonance between N,N-dimethylacetamide and the target amide using an isodesmic trans-amidation process and is calibrated relative to 1-aza-2-adamantanone with zero amidicity and N,N-dimethylace- tamide with 100% amidicity. Results indicate excellent coherence between the methods, which must be regarded as more reliable than a recently reported approach to amidicities based upon enthalpies of hydrogenation. Data for acyclic planar and twisted amides are predictable on the basis of the degrees of pyramidalization at nitrogen and twisting about the C−N bonds. Monocyclic lactams are predicted to have amidicities at least as high as N,N-dimethylacetamide, and the β-lactam system is planar with greater amide resonance than that of N,N- dimethylacetamide. Bicyclic penam/em and cepham/em scaffolds lose some amidicity in line with the degree of strain-induced pyramidalization at the bridgehead nitrogen and twist about the amide bond, but the most puckered penem system still retains substantial amidicity equivalent to 73% that of N,N-dimethylacetamide. ■ INTRODUCTION completed by a third resonance form, III, with no C−N pi Amide linkages are ubiquitous in proteins, peptides, and natural character and on account of positive polarity at carbon and the or synthetic molecules and in most of these they possess, electronegativity of nitrogen, must be destabilizing. -

The Birth of Modern Chemistry

The Birth of Modern Chemistry 3rd semester project, Fall 2008 NIB Group nr.5, House 13.2 Thomas Allan Rayner & Aiga Mackevica Supervisor: Torben Brauner Abstract Alchemy was a science practiced for more than two millennia up till the end of 18th century when it was replaced by modern chemistry, which is practiced up till this very day. The purpose of this report is to look into this shift and investigate whether this shift can be classified as a paradigm shift according to the famous philosopher Thomas Kuhn, who came up with a theory on the structure of scientific revolutions. In order to come to draw any kind of conclusions, the report summarizes and defines the criteria for what constitutes a paradigm, crisis and paradigm shift, which are all important in order to investigate the manner in which a paradigm shift occurs. The criteria are applied to the historical development of modern chemistry and alchemy as well as the transition between the two sciences. As a result, alchemy and modern chemistry satisfy the requirements and can be viewed as two different paradigms in a Kuhnian sense. However, it is debatable whether the shift from alchemy to modern chemistry can be called a paradigm shift. 2 Acknowledgments We would like to thank Torben Brauner for his guidance throughout the project period as our supervisor. We would also like to thank our opposing group – Paula Melo Paulon Hansen, Stine Hesselholt Sloth and their supervisor Ole Andersen for their advice and critique for our project. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 2. -

Chapter 19 Chemical Thermodynamics

Chapter 19 Chemical Thermodynamics Entropy and free energy Learning goals and key skills: Explain and apply the terms spontaneous process, reversible process, irreversible process, and isothermal process. Define entropy and state the second law of thermodynamics. Calculate DS for a phase change. Explain how the entropy of a system is related to the number of possible microstates. Describe the kinds of molecular motion that a molecule can possess. Predict the sign of DS for physical and chemical processes. State the third law of thermodynamics. Compare the values of standard molar entropies. Calculate standard entropy changes for a system from standard molar entropies. Calculate the Gibbs free energy from the enthalpy change and entropy change at a given temperature. Use free energy changes to predict whether reactions are spontaneous. Calculate standard free energy changes using standard free energies of formation. Predict the effect of temperature on spontaneity given DH and DS. Calculate DG under nonstandard conditions. Relate DG°and equilibrium constant (K). Review Chapter 5: energy, enthalpy, 1st law of thermo Thermodynamics: the science of heat and work Thermochemistry: the relationship between chemical reactions and energy changes Energy (E) The capacity to do work or to transfer heat. Work (w) The energy expended to move an object against an opposing force. w = F d Heat (q) Derived from the movements of atoms and molecules (including vibrations and rotations). Enthalpy (H) Enthalpy is the heat absorbed (or released) by a system during a constant-pressure process. 1 0th Law of Thermodynamics If A is in thermal equilibrium with B, and B is in thermal equilibrium with C, then C is also in thermal equilibrium with A. -

General Chemistry Course Description

Chemistry 110: General Chemistry Note: this is a representative syllabus for Chemistry 110. It is here for informational purposes. It is not intended to substitute for or replace the syllabus your instructor provides. Course Description: Introduction to the general principles of chemistry for students planning a professional career in chemistry, a related science, the health professions, or engineering. Stoichiometry, atomic structure, chemical bonding and geometry, thermochemistry, gases, types of chemical reactions, statistics. Weekly laboratory exercises emphasize quantitative techniques and complement the lecture material. Weekly discussion sessions focus on homework assignments and lecture material. Prerequisite: Mathematics 055 or equivalent. Previous high school chemistry not required. Taught: Annually, 5 semester credits. Course Components: Lecture, Recitation section, Laboratory Textbook: Steven S. Zumdahl and Susan A. Zumdahl, Chemistry, 5th Ed., Houghton Mifflin Company (New York, 2000). The text is available in the college bookstore. Lab Manual: Chemistry Department Faculty, Chemistry 110 Lab Manual, Fall, 2001 Edition, Kinkos. These may be purchased from Linda Noble, the Chemistry Secretary. Safety Goggles: These must be worn at all times in the laboratory. They can be purchased in the college bookstore. Calculator: Must have logs and exponential capability. Lab Notebook: This is a bound duplicate notebook with numbered pages. It can be purchased in the college bookstore Lecture Schedule 1.1-1.5 introduction, laboratory precision -

Course Syllabus

Course Syllabus Department: Science & Technology Date: January 2015 I. Course Prefix and Number: CHM 205 Course Name: Organic Chemistry I – Lecture Only Credit Hours and Contact Hours: 4 credit hours and 4 (3:0:1) contact hours Catalog Description including pre- and co-requisites: A systematic study of the chemistry of carbon compounds emphasizing reactions, mechanisms, and synthesis with a focus on functional groups, addition reactions to alkenes and alkynes, alcohols and ethers, stereochemistry, nomenclature, acid-base chemistry, reaction kinetics and thermodynamics. Completion of General Chemistry II or equivalent with a grade of C or better is prerequisite. II. Course Outcomes and Objectives Student Learning Outcomes: Upon completion of this course, the student will be able to: Demonstrate an understanding of basic principles of organic chemistry and how they relate to everyday experiences. Demonstrate problem solving and critical thinking skills Apply methods of scientific inquiry. Apply problem solving techniques to real-world problems. Demonstrate an understanding of the chemical environment and the role that organic molecules play in the natural and the synthetic world. Relationship to Academic Programs and Curriculum: This course is required for majors in chemistry, chemical engineering, biology, biotechnology, pharmacology, and other pre-professional programs. College Learning Outcomes Addressed by the Course: writing computer literacy oral communications ethics/values X reading citizenship mathematics global concerns X critical thinking information resources 1 III. Instructional Materials and Methods Types of Course Materials: A standard two-semester 200 level organic textbook and workbook. Methods of Instruction (e.g. Lecture and Seminar …): Three hours of lecture, with a one hour recitation period for individual as well as group learning activities such as case studies and guided learning activities. -

Entropy and Free Energy

Spontaneous Change: Entropy and Free Energy 2nd and 3rd Laws of Thermodynamics Problem Set: Chapter 20 questions 29, 33, 39, 41, 43, 45, 49, 51, 60, 63, 68, 75 The second law of thermodynamics looks mathematically simple but it has so many subtle and complex implications that it makes most chemistry majors sweat a lot before (and after) they graduate. Fortunately its practical, down-to-earth applications are easy and crystal clear. We can build on those to get to very sophisticated conclusions about the behavior of material substances and objects in our lives. Frank L. Lambert Experimental Observations that Led to the Formulation of the 2nd Law 1) It is impossible by a cycle process to take heat from the hot system and convert it into work without at the same time transferring some heat to cold surroundings. In the other words, the efficiency of an engine cannot be 100%. (Lord Kelvin) 2) It is impossible to transfer heat from a cold system to a hot surroundings without converting a certain amount of work into additional heat of surroundings. In the other words, a refrigerator releases more heat to surroundings than it takes from the system. (Clausius) Note 1: Even though the need to describe an engine and a refrigerator resulted in formulating the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics, this law is universal (similarly to the 1st Law) and applicable to all processes. Note 2: To use the Laws of Thermodynamics we need to understand what the system and surroundings are. Universe = System + Surroundings universe Matter Surroundings (Huge) Work System Matter, Heat, Work Heat 1. -

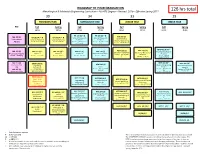

BS Metallurgical Engineering Curriculum Flowchart

ROADMAP TO YOUR GRADUATION Metallurgical & Materials Engineering Curriculum – BS MTE Degree – Revised 2016-- Effective Spring 2017 126 hrs total 30 34 33 29 FRESHMAN YEAR SOPHOMORE YEAR JUNIOR YEAR SENIOR YEAR Pre Fall SprIng Fall SprIng Fall SprIng Fall SprIng 16 hrs 14 hrs 17 hrs 17 hrs 16 hrs 17 hrs 14 hrs 15 hrs PH 105 (4) * N PH 106 (4) * N ECE 320 (3) MA 100 (3) CH 101 (4) * N CH 102 (4) * N General Physics with General Physics with Fundamentals of Intermediate General Chemistry 1 General Chemistry 2 Calculus 1 Calculus 2 Electrical Engineering Pre-reqs. = See catalog Pre-reqs. = CH 101 Pre-reqs. = MA 113 or 115 Pre-reqs. = PH 101 or 105 or Algebra Pre-reqs. = PH 106, MA 238 or 125 or 145 125 MTE 481 (4) W * AEM 250 (3) MTE 455 (4) MA 112 (3) MA 125 (4) * MA 126 (4) * MA 227 (4) MA 238 (3) Analytical Methods for Mechanics of Materials Mechanical Behavior of Precalculus Algebra Calculus 1 Calculus 2 Calculus 3 Differential Equations 1 Materials Pre-reqs. = MA 126, AEM Materials Pre-reqs. = See catalog Pre-reqs. = See catalog Pre-reqs. = MA 125 Pre-reqs. = MA 126 Pre-reqs. = MA 126 Pre-req. = MA 238 201 Pre-reqs. = AEM 250 Co-req. = MTE 441 # MA 113 (3) ENGR 103 (3) MTE 443 (3) MTE 445 (3) # AEM 201 (3) Materials Engineering Precalculus Trig Engineering Materials Engineering Statics Design 1 OR Foundations Design 2 Pre-reqs. = MA 125, PH 105, Pre-reqs. = MTE 362, 373, Pre-reqs. = MATH 125 or Pre-reqs. -

Professor of Chemistry

Bruce C. Gibb FRSC Professor of Chemistry Department of Chemistry Tulane University New Orleans, LA 70118, USA Tel: (504) 862 8136 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.gibbgroup.org Twitter: @brucecgibb Research Interests: Aqueous supramolecular chemistry: understanding how molecules interact in water: from specific ion- pairing and the hydrophobic effect, to protein aggregation pertinent to neurodegenerative disorders. Our research has primarily focused on: 1) novel hosts designed to probe the hydrophobic, Hofmeister, and Reverse Hofmeister effects, and; 2) designing supramolecular capsules as yocto-liter reaction vessels and separators. Current efforts to probe the hydrophobic and Hofmeister effects include studies of the supramolecular properties of proteins. Professional Positions: Visiting Professor, Wuhan University of Science and Technology as a Chair Professor of Chutian Scholars Program (2015-2018) Professor of Chemistry, Tulane University, New Orleans, USA (2012-present). University Research Professor, University of New Orleans, USA (2007-2011). Professor of Chemistry, University of New Orleans, USA (2005-2007). Associate Professor of Chemistry, University of New Orleans, USA (2002-2005). Assistant Professor of Chemistry, University of New Orleans, USA, (1996-2002). Education: Postdoctoral Work Department of Chemistry, New York University. Synthesis of Carbonic Anhydrase (CA) mimics with Advisor: Prof. J. W. Canary, (1994-1996). Department of Chemistry, University of British Columbia, Canada De Novo Protein development. Advisor: Prof. J. C. Sherman (1993-1994). Ph.D. Robert Gordon’s University, Aberdeen, UK. Synthesis and Structural Examination of 3a,5-cyclo-5a- Androstane Steroids. Advisors: Dr. Philip J. Cox and Dr. Steven MacManus (1987-92) . B.Sc. with Honors in Physical Sciences Robert Gordon’s University, Aberdeen, UK. -

Chemistry (CH) 1

Chemistry (CH) 1 Chemistry (CH) CH 101 - INTRO TO CHEMISTRY Semester Hours: 3 Properties of solids, liquids, gases, and solutions, atomic theory and bonding, concentration concepts, and physical and chemical properties of the more common elements and their compounds. No placement examination is required. Prerequisite: MA 110 or prerequisites with concurrency MA 112 or higher and CH 105. CH 101R - RECITATION Semester Hours: 0 CH 105 - INTRO CHEMISTRY LAB Semester Hour: 1 Complements the lecture material for CH 101. Laboratory fundamentals and basic chemical principles. Prerequisite with concurrency: CH 101. CH 121 - GENERAL CHEMISTRY I Semester Hours: 3 For science and engineering majors. Chemical properties of elements, their periodic groups, and their compounds. Reactions and stoichiometry. Nature of the chemical bond, molecular structure, thermochemistry. Properties of gases, liquids, and solids. Prerequisite: CH 101 or placement test. Prerequisites with concurrency: MA 113 or higher, and CH 125. CH 121M - GENERAL CHEMISTRY FOR CHEMISTS Semester Hours: 3 For Chemistry Majors and Minors. Chemical properties of elements and the Periodic Table. Reactions and stoichiometry. Nature of chemical bonds, molecular structure, thermochemistry. Properties of gases, liquids, and solids. Intro to your exciting Department and its programs. Engagement activities. Prerequisites: CH 101 or Placement. Prerequisites with concurrency: MA 113 or higher, CH 125. CH 121R - RECITATION Semester Hours: 0 CH 122 - GENERAL CHEMISTRY ENGINEERS Semester Hours: 3 This course is designed as a one semester presentation of key aspects in general chemistry and is recommended for all engineering majors except chemical engineers. Covers topic on atoms and molecules: reactions and stoichiometry; gases; the periodic table; atomic structure, chemical bonding and molecular structure; materials; energy, entropy, and free energy; kinetics and equilibrium; and electrochemistry. -

Chemistry 130 Gibbs Free Energy

Chemistry 130 Gibbs Free Energy Dr. John F. C. Turner 409 Buehler Hall [email protected] Chemistry 130 Equilibrium and energy So far in chemistry 130, and in Chemistry 120, we have described chemical reactions thermodynamically by using U - the change in internal energy, U, which involves heat transferring in or out of the system only or H - the change in enthalpy, H, which involves heat transfers in and out of the system as well as changes in work. U applies at constant volume, where as H applies at constant pressure. Chemistry 130 Equilibrium and energy When chemical systems change, either physically through melting, evaporation, freezing or some other physical process variables (V, P, T) or chemically by reaction variables (ni) they move to a point of equilibrium by either exothermic or endothermic processes. Characterizing the change as exothermic or endothermic does not tell us whether the change is spontaneous or not. Both endothermic and exothermic processes are seen to occur spontaneously. Chemistry 130 Equilibrium and energy Our descriptions of reactions and other chemical changes are on the basis of exothermicity or endothermicity ± whether H is negative or positive H is negative ± exothermic H is positive ± endothermic As a description of changes in heat content and work, these are adequate but they do not describe whether a process is spontaneous or not. There are endothermic processes that are spontaneous ± evaporation of water, the dissolution of ammonium chloride in water, the melting of ice and so on. We need a thermodynamic description of spontaneous processes in order to fully describe a chemical system Chemistry 130 Equilibrium and energy A spontaneous process is one that takes place without any influence external to the system.