Chemistry 130 Gibbs Free Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, Heat, and Entropy

3.012 Fundamentals of Materials Science Fall 2005 Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, heat, and entropy Today: LAST TIME .........................................................................................................................................................................................2� State functions ..............................................................................................................................................................................2� Path dependent variables: heat and work..................................................................................................................................2� DEFINING TEMPERATURE ...................................................................................................................................................................4� The zeroth law of thermodynamics .............................................................................................................................................4� The absolute temperature scale ..................................................................................................................................................5� CONSEQUENCES OF THE RELATION BETWEEN TEMPERATURE, HEAT, AND ENTROPY: HEAT CAPACITY .......................................6� The difference between heat and temperature ...........................................................................................................................6� Defining heat capacity.................................................................................................................................................................6� -

Chapter 3. Second and Third Law of Thermodynamics

Chapter 3. Second and third law of thermodynamics Important Concepts Review Entropy; Gibbs Free Energy • Entropy (S) – definitions Law of Corresponding States (ch 1 notes) • Entropy changes in reversible and Reduced pressure, temperatures, volumes irreversible processes • Entropy of mixing of ideal gases • 2nd law of thermodynamics • 3rd law of thermodynamics Math • Free energy Numerical integration by computer • Maxwell relations (Trapezoidal integration • Dependence of free energy on P, V, T https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trapezoidal_rule) • Thermodynamic functions of mixtures Properties of partial differential equations • Partial molar quantities and chemical Rules for inequalities potential Major Concept Review • Adiabats vs. isotherms p1V1 p2V2 • Sign convention for work and heat w done on c=C /R vm system, q supplied to system : + p1V1 p2V2 =Cp/CV w done by system, q removed from system : c c V1T1 V2T2 - • Joule-Thomson expansion (DH=0); • State variables depend on final & initial state; not Joule-Thomson coefficient, inversion path. temperature • Reversible change occurs in series of equilibrium V states T TT V P p • Adiabatic q = 0; Isothermal DT = 0 H CP • Equations of state for enthalpy, H and internal • Formation reaction; enthalpies of energy, U reaction, Hess’s Law; other changes D rxn H iD f Hi i T D rxn H Drxn Href DrxnCpdT Tref • Calorimetry Spontaneous and Nonspontaneous Changes First Law: when one form of energy is converted to another, the total energy in universe is conserved. • Does not give any other restriction on a process • But many processes have a natural direction Examples • gas expands into a vacuum; not the reverse • can burn paper; can't unburn paper • heat never flows spontaneously from cold to hot These changes are called nonspontaneous changes. -

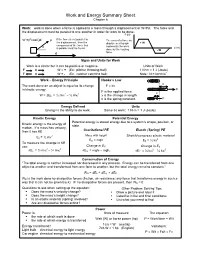

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6

Work and Energy Summary Sheet Chapter 6 Work: work is done when a force is applied to a mass through a displacement or W=Fd. The force and the displacement must be parallel to one another in order for work to be done. F (N) W =(Fcosθ)d F If the force is not parallel to The area of a force vs. the displacement, then the displacement graph + W component of the force that represents the work θ d (m) is parallel must be found. done by the varying - W d force. Signs and Units for Work Work is a scalar but it can be positive or negative. Units of Work F d W = + (Ex: pitcher throwing ball) 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) F d W = - (Ex. catcher catching ball) Note: N = kg m/s2 • Work – Energy Principle Hooke’s Law x The work done on an object is equal to its change F = kx in kinetic energy. F F is the applied force. 2 2 x W = ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi x is the change in length. k is the spring constant. F Energy Defined Units Energy is the ability to do work. Same as work: 1 N•m = 1 J (Joule) Kinetic Energy Potential Energy Potential energy is stored energy due to a system’s shape, position, or Kinetic energy is the energy of state. motion. If a mass has velocity, Gravitational PE Elastic (Spring) PE then it has KE 2 Mass with height Stretch/compress elastic material Ek = ½ mv 2 EG = mgh EE = ½ kx To measure the change in KE Change in E use: G Change in ES 2 2 2 2 ΔEk = ½ mvf – ½ mvi ΔEG = mghf – mghi ΔEE = ½ kxf – ½ kxi Conservation of Energy “The total energy is neither increased nor decreased in any process. -

Thermodynamics

ME346A Introduction to Statistical Mechanics { Wei Cai { Stanford University { Win 2011 Handout 6. Thermodynamics January 26, 2011 Contents 1 Laws of thermodynamics 2 1.1 The zeroth law . .3 1.2 The first law . .4 1.3 The second law . .5 1.3.1 Efficiency of Carnot engine . .5 1.3.2 Alternative statements of the second law . .7 1.4 The third law . .8 2 Mathematics of thermodynamics 9 2.1 Equation of state . .9 2.2 Gibbs-Duhem relation . 11 2.2.1 Homogeneous function . 11 2.2.2 Virial theorem / Euler theorem . 12 2.3 Maxwell relations . 13 2.4 Legendre transform . 15 2.5 Thermodynamic potentials . 16 3 Worked examples 21 3.1 Thermodynamic potentials and Maxwell's relation . 21 3.2 Properties of ideal gas . 24 3.3 Gas expansion . 28 4 Irreversible processes 32 4.1 Entropy and irreversibility . 32 4.2 Variational statement of second law . 32 1 In the 1st lecture, we will discuss the concepts of thermodynamics, namely its 4 laws. The most important concepts are the second law and the notion of Entropy. (reading assignment: Reif x 3.10, 3.11) In the 2nd lecture, We will discuss the mathematics of thermodynamics, i.e. the machinery to make quantitative predictions. We will deal with partial derivatives and Legendre transforms. (reading assignment: Reif x 4.1-4.7, 5.1-5.12) 1 Laws of thermodynamics Thermodynamics is a branch of science connected with the nature of heat and its conver- sion to mechanical, electrical and chemical energy. (The Webster pocket dictionary defines, Thermodynamics: physics of heat.) Historically, it grew out of efforts to construct more efficient heat engines | devices for ex- tracting useful work from expanding hot gases (http://www.answers.com/thermodynamics). -

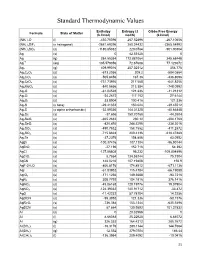

Standard Thermodynamic Values

Standard Thermodynamic Values Enthalpy Entropy (J Gibbs Free Energy Formula State of Matter (kJ/mol) mol/K) (kJ/mol) (NH4)2O (l) -430.70096 267.52496 -267.10656 (NH4)2SiF6 (s hexagonal) -2681.69296 280.24432 -2365.54992 (NH4)2SO4 (s) -1180.85032 220.0784 -901.90304 Ag (s) 0 42.55128 0 Ag (g) 284.55384 172.887064 245.68448 Ag+1 (aq) 105.579056 72.67608 77.123672 Ag2 (g) 409.99016 257.02312 358.778 Ag2C2O4 (s) -673.2056 209.2 -584.0864 Ag2CO3 (s) -505.8456 167.36 -436.8096 Ag2CrO4 (s) -731.73976 217.568 -641.8256 Ag2MoO4 (s) -840.5656 213.384 -748.0992 Ag2O (s) -31.04528 121.336 -11.21312 Ag2O2 (s) -24.2672 117.152 27.6144 Ag2O3 (s) 33.8904 100.416 121.336 Ag2S (s beta) -29.41352 150.624 -39.45512 Ag2S (s alpha orthorhombic) -32.59336 144.01328 -40.66848 Ag2Se (s) -37.656 150.70768 -44.3504 Ag2SeO3 (s) -365.2632 230.12 -304.1768 Ag2SeO4 (s) -420.492 248.5296 -334.3016 Ag2SO3 (s) -490.7832 158.1552 -411.2872 Ag2SO4 (s) -715.8824 200.4136 -618.47888 Ag2Te (s) -37.2376 154.808 43.0952 AgBr (s) -100.37416 107.1104 -96.90144 AgBrO3 (s) -27.196 152.716 54.392 AgCl (s) -127.06808 96.232 -109.804896 AgClO2 (s) 8.7864 134.55744 75.7304 AgCN (s) 146.0216 107.19408 156.9 AgF•2H2O (s) -800.8176 174.8912 -671.1136 AgI (s) -61.83952 115.4784 -66.19088 AgIO3 (s) -171.1256 149.3688 -93.7216 AgN3 (s) 308.7792 104.1816 376.1416 AgNO2 (s) -45.06168 128.19776 19.07904 AgNO3 (s) -124.39032 140.91712 -33.472 AgO (s) -11.42232 57.78104 14.2256 AgOCN (s) -95.3952 121.336 -58.1576 AgReO4 (s) -736.384 153.1344 -635.5496 AgSCN (s) 87.864 130.9592 101.37832 Al (s) -

Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, Thermodynamic Inequalities

Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, Thermodynamic Inequalities Chapter II. Thermodynamic Quantities A.G. Petukhov, PHYS 743 October 4, 2017 Chapter II. Thermodynamic Quantities Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, ThermodynamicA.G. Petukhov,October Inequalities PHYS 4, 743 2017 1 / 12 Maximum Work If a thermally isolated system is in non-equilibrium state it may do work on some external bodies while equilibrium is being established. The total work done depends on the way leading to the equilibrium. Therefore the final state will also be different. In any event, since system is thermally isolated the work done by the system: jAj = E0 − E(S); where E0 is the initial energy and E(S) is final (equilibrium) one. Le us consider the case when Vinit = Vfinal but can change during the process. @ jAj @E = − = −Tfinal < 0 @S @S V The entropy cannot decrease. Then it means that the greater is the change of the entropy the smaller is work done by the system The maximum work done by the system corresponds to the reversible process when ∆S = Sfinal − Sinitial = 0 Chapter II. Thermodynamic Quantities Lecture 8: Maximum and Minimum Work, ThermodynamicA.G. Petukhov,October Inequalities PHYS 4, 743 2017 2 / 12 Clausius Theorem dS 0 R > dS < 0 R S S TA > TA T > T B B A δQA > 0 B Q 0 δ B < The system following a closed path A: System receives heat from a hot reservoir. Temperature of the thermostat is slightly larger then the system temperature B: System dumps heat to a cold reservoir. Temperature of the system is slightly larger then that of the thermostat Chapter II. -

Entropy: Is It What We Think It Is and How Should We Teach It?

Entropy: is it what we think it is and how should we teach it? David Sands Dept. Physics and Mathematics University of Hull UK Institute of Physics, December 2012 We owe our current view of entropy to Gibbs: “For the equilibrium of any isolated system it is necessary and sufficient that in all possible variations of the system that do not alter its energy, the variation of its entropy shall vanish or be negative.” Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances, 1875 And Maxwell: “We must regard the entropy of a body, like its volume, pressure, and temperature, as a distinct physical property of the body depending on its actual state.” Theory of Heat, 1891 Clausius: Was interested in what he called “internal work” – work done in overcoming inter-particle forces; Sought to extend the theory of cyclic processes to cover non-cyclic changes; Actively looked for an equivalent equation to the central result for cyclic processes; dQ 0 T Clausius: In modern thermodynamics the sign is negative, because heat must be extracted from the system to restore the original state if the cycle is irreversible . The positive sign arises because of Clausius’ view of heat; not caloric but still a property of a body The transformation of heat into work was something that occurred within a body – led to the notion of “equivalence value”, Q/T Clausius: Invented the concept “disgregation”, Z, to extend the ideas to irreversible, non-cyclic processes; TdZ dI dW Inserted disgregation into the First Law; dQ dH TdZ 0 Clausius: Changed the sign of dQ;(originally dQ=dH+AdL; dL=dI+dW) dHdQ Derived; dZ 0 T dH Called; dZ the entropy of a body. -

Chapter 19 Chemical Thermodynamics

Chapter 19 Chemical Thermodynamics Entropy and free energy Learning goals and key skills: Explain and apply the terms spontaneous process, reversible process, irreversible process, and isothermal process. Define entropy and state the second law of thermodynamics. Calculate DS for a phase change. Explain how the entropy of a system is related to the number of possible microstates. Describe the kinds of molecular motion that a molecule can possess. Predict the sign of DS for physical and chemical processes. State the third law of thermodynamics. Compare the values of standard molar entropies. Calculate standard entropy changes for a system from standard molar entropies. Calculate the Gibbs free energy from the enthalpy change and entropy change at a given temperature. Use free energy changes to predict whether reactions are spontaneous. Calculate standard free energy changes using standard free energies of formation. Predict the effect of temperature on spontaneity given DH and DS. Calculate DG under nonstandard conditions. Relate DG°and equilibrium constant (K). Review Chapter 5: energy, enthalpy, 1st law of thermo Thermodynamics: the science of heat and work Thermochemistry: the relationship between chemical reactions and energy changes Energy (E) The capacity to do work or to transfer heat. Work (w) The energy expended to move an object against an opposing force. w = F d Heat (q) Derived from the movements of atoms and molecules (including vibrations and rotations). Enthalpy (H) Enthalpy is the heat absorbed (or released) by a system during a constant-pressure process. 1 0th Law of Thermodynamics If A is in thermal equilibrium with B, and B is in thermal equilibrium with C, then C is also in thermal equilibrium with A. -

Lecture 6: Entropy

Matthew Schwartz Statistical Mechanics, Spring 2019 Lecture 6: Entropy 1 Introduction In this lecture, we discuss many ways to think about entropy. The most important and most famous property of entropy is that it never decreases Stot > 0 (1) Here, Stot means the change in entropy of a system plus the change in entropy of the surroundings. This is the second law of thermodynamics that we met in the previous lecture. There's a great quote from Sir Arthur Eddington from 1927 summarizing the importance of the second law: If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell's equationsthen so much the worse for Maxwell's equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observationwell these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of ther- modynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation. Another possibly relevant quote, from the introduction to the statistical mechanics book by David Goodstein: Ludwig Boltzmann who spent much of his life studying statistical mechanics, died in 1906, by his own hand. Paul Ehrenfest, carrying on the work, died similarly in 1933. Now it is our turn to study statistical mechanics. There are many ways to dene entropy. All of them are equivalent, although it can be hard to see. In this lecture we will compare and contrast dierent denitions, building up intuition for how to think about entropy in dierent contexts. The original denition of entropy, due to Clausius, was thermodynamic. -

Energy and Enthalpy Thermodynamics

Energy and Energy and Enthalpy Thermodynamics The internal energy (E) of a system consists of The energy change of a reaction the kinetic energy of all the particles (related to is measured at constant temperature) plus the potential energy of volume (in a bomb interaction between the particles and within the calorimeter). particles (eg bonding). We can only measure the change in energy of the system (units = J or Nm). More conveniently reactions are performed at constant Energy pressure which measures enthalpy change, ∆H. initial state final state ∆H ~ ∆E for most reactions we study. final state initial state ∆H < 0 exothermic reaction Energy "lost" to surroundings Energy "gained" from surroundings ∆H > 0 endothermic reaction < 0 > 0 2 o Enthalpy of formation, fH Hess’s Law o Hess's Law: The heat change in any reaction is the The standard enthalpy of formation, fH , is the change in enthalpy when one mole of a substance is formed from same whether the reaction takes place in one step or its elements under a standard pressure of 1 atm. several steps, i.e. the overall energy change of a reaction is independent of the route taken. The heat of formation of any element in its standard state is defined as zero. o The standard enthalpy of reaction, H , is the sum of the enthalpy of the products minus the sum of the enthalpy of the reactants. Start End o o o H = prod nfH - react nfH 3 4 Example Application – energy foods! Calculate Ho for CH (g) + 2O (g) CO (g) + 2H O(l) Do you get more energy from the metabolism of 1.0 g of sugar or -

Work-Energy for a System of Particles and Its Relation to Conservation Of

Conservation of Energy, the Work-Energy Principle, and the Mechanical Energy Balance In your study of engineering and physics, you will run across a number of engineering concepts related to energy. Three of the most common are Conservation of Energy, the Work-Energy Principle, and the Mechanical Engineering Balance. The Conservation of Energy is treated in this course as one of the overarching and fundamental physical laws. The other two concepts are special cases and only apply under limited conditions. The purpose of this note is to review the pedigree of the Work-Energy Principle, to show how the more general Mechanical Energy Bal- ance is developed from Conservation of Energy, and finally to describe the conditions under which the Mechanical Energy Balance is preferred over the Work-Energy Principle. Work-Energy Principle for a Particle Consider a particle of mass m and velocity V moving in a gravitational field of strength g sub- G ject to a surface force Rsurface . Under these conditions, writing Conservation of Linear Momen- tum for the particle gives the following: d mV= R+ mg (1.1) dt ()Gsurface Forming the dot product of Eq. (1.1) with the velocity of the particle and rearranging terms gives the rate form of the Work-Energy Principle for a particle: 2 dV⎛⎞ d d ⎜⎟mmgzRV+=() surfacei G ⇒ () EEWK += GP mech, in (1.2) dt⎝⎠2 dt dt Gravitational mechanical Kinetic potential power into energy energy the system Recall that mechanical power is defined as WRmech, in= surfaceiV G , the dot product of the surface force with the velocity of its point of application. -

Entropy and Free Energy

Spontaneous Change: Entropy and Free Energy 2nd and 3rd Laws of Thermodynamics Problem Set: Chapter 20 questions 29, 33, 39, 41, 43, 45, 49, 51, 60, 63, 68, 75 The second law of thermodynamics looks mathematically simple but it has so many subtle and complex implications that it makes most chemistry majors sweat a lot before (and after) they graduate. Fortunately its practical, down-to-earth applications are easy and crystal clear. We can build on those to get to very sophisticated conclusions about the behavior of material substances and objects in our lives. Frank L. Lambert Experimental Observations that Led to the Formulation of the 2nd Law 1) It is impossible by a cycle process to take heat from the hot system and convert it into work without at the same time transferring some heat to cold surroundings. In the other words, the efficiency of an engine cannot be 100%. (Lord Kelvin) 2) It is impossible to transfer heat from a cold system to a hot surroundings without converting a certain amount of work into additional heat of surroundings. In the other words, a refrigerator releases more heat to surroundings than it takes from the system. (Clausius) Note 1: Even though the need to describe an engine and a refrigerator resulted in formulating the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics, this law is universal (similarly to the 1st Law) and applicable to all processes. Note 2: To use the Laws of Thermodynamics we need to understand what the system and surroundings are. Universe = System + Surroundings universe Matter Surroundings (Huge) Work System Matter, Heat, Work Heat 1.