Heteroatom Substitution at Amide Nitrogen—Resonance Reduction and HERON Reactions of Anomeric Amides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organocatalytic Asymmetric N-Sulfonyl Amide C-N Bond Activation to Access Axially Chiral Biaryl Amino Acids

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14799-8 OPEN Organocatalytic asymmetric N-sulfonyl amide C-N bond activation to access axially chiral biaryl amino acids Guanjie Wang1, Qianqian Shi2, Wanyao Hu1, Tao Chen1, Yingying Guo1, Zhouli Hu1, Minghua Gong1, ✉ ✉ ✉ Jingcheng Guo1, Donghui Wei 2 , Zhenqian Fu 1,3 & Wei Huang1,3 1234567890():,; Amides are among the most fundamental functional groups and essential structural units, widely used in chemistry, biochemistry and material science. Amide synthesis and trans- formations is a topic of continuous interest in organic chemistry. However, direct catalytic asymmetric activation of amide C-N bonds still remains a long-standing challenge due to high stability of amide linkages. Herein, we describe an organocatalytic asymmetric amide C-N bonds cleavage of N-sulfonyl biaryl lactams under mild conditions, developing a general and practical method for atroposelective construction of axially chiral biaryl amino acids. A structurally diverse set of axially chiral biaryl amino acids are obtained in high yields with excellent enantioselectivities. Moreover, a variety of axially chiral unsymmetrical biaryl organocatalysts are efficiently constructed from the resulting axially chiral biaryl amino acids by our present strategy, and show competitive outcomes in asymmetric reactions. 1 Key Laboratory of Flexible Electronics & Institute of Advanced Materials, Jiangsu National Synergetic Innovation Center for Advanced Materials, Nanjing Tech University, 30 South Puzhu Road, Nanjing 211816, China. 2 College -

Reliable Determination of Amidicity in Acyclic Amides and Lactams Stephen A

Article pubs.acs.org/joc Reliable Determination of Amidicity in Acyclic Amides and Lactams Stephen A. Glover* and Adam A. Rosser Department of Chemistry, School of Science and Technology, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: Two independent computational methods have been used for determination of amide resonance stabilization and amidicities relative to N,N-dimethylacetamide for a wide range of acyclic and cyclic amides. The first method utilizes carbonyl substitution nitrogen atom replacement (COSNAR). The second, new approach involves determination of the difference in amide resonance between N,N-dimethylacetamide and the target amide using an isodesmic trans-amidation process and is calibrated relative to 1-aza-2-adamantanone with zero amidicity and N,N-dimethylace- tamide with 100% amidicity. Results indicate excellent coherence between the methods, which must be regarded as more reliable than a recently reported approach to amidicities based upon enthalpies of hydrogenation. Data for acyclic planar and twisted amides are predictable on the basis of the degrees of pyramidalization at nitrogen and twisting about the C−N bonds. Monocyclic lactams are predicted to have amidicities at least as high as N,N-dimethylacetamide, and the β-lactam system is planar with greater amide resonance than that of N,N- dimethylacetamide. Bicyclic penam/em and cepham/em scaffolds lose some amidicity in line with the degree of strain-induced pyramidalization at the bridgehead nitrogen and twist about the amide bond, but the most puckered penem system still retains substantial amidicity equivalent to 73% that of N,N-dimethylacetamide. ■ INTRODUCTION completed by a third resonance form, III, with no C−N pi Amide linkages are ubiquitous in proteins, peptides, and natural character and on account of positive polarity at carbon and the or synthetic molecules and in most of these they possess, electronegativity of nitrogen, must be destabilizing. -

UNIT – I Nomenclature of Organic Compounds and Reaction Intermediates

UNIT – I Nomenclature of organic Compounds and Reaction Intermediates Two Marks 1. Give IUPAC name for the compounds. 2. Write the stability of Carbocations. 3. What are Carbenes? 4. How Carbanions reacts? Give examples 5. Write the reactions of free radicals 6. How singlet and triplet carbenes react? 7. How arynes are formed? 8. What are Nitrenium ion? 9. Give the structure of carbenes and Nitrenes 10. Write the structure of carbocations and carbanions. 11. Give the generation of carbenes and nitrenes. 12. What are non-classical carbocations? 13. How free radicals are formed and give its generation? 14. What is [1,2] shift? Five Marks 1. Explain the generation, Stability, Structure and reactivity of Nitrenes 2. Explain the generation, Stability, Structure and reactivity of Free Radicals 3. Write a short note on Non-Classical Carbocations. 4. Explain Fries rearrangement with mechanism. 5. Explain the reaction and mechanism of Sommelet-Hauser rearrangement. 6. Explain Favorskii rearrangement with mechanism. 7. Explain the mechanism of Hofmann rearrangement. Ten Marks 1. Explain brefly about generation, Stability, Structure and reactivity of Carbocations 2. Explain the generation, Stability, Structure and reactivity of Carbenes in detailed 3. Explain the generation, Stability, Structure and reactivity of Carboanions. 4. Explain brefly the mechanism and reaction of [1,2] shift. 5. Explain the mechanism of the following rearrangements i) Wolf rearrangement ii) Stevens rearrangement iii) Benzidine rearragement 6. Explain the reaction and mechanism of Dienone-Phenol reaarangement in detailed 7. Explain the reaction and mechanism of Baeyer-Villiger rearrangement in detailed Compounds classified as heterocyclic probably constitute the largest and most varied family of organic compounds. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer primer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, prim bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g^ maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Bell & Howell Intormaiion Company 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor Ml 46106*1346 USA 313/761-4700 800.521-0600 EXPLORATORY PHOTOCHEMISTRY OF POLYFLUORINATED ARYL AZIDES IN NEUTRAL AND ACIDIC MEDIA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hongbin Zhai ***** The Ohio State University 1995 Dissertation Committee: Approved By Matthew S. -

Electrochemistry and Photoredox Catalysis: a Comparative Evaluation in Organic Synthesis

molecules Review Electrochemistry and Photoredox Catalysis: A Comparative Evaluation in Organic Synthesis Rik H. Verschueren and Wim M. De Borggraeve * Department of Chemistry, Molecular Design and Synthesis, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200F, box 2404, 3001 Leuven, Belgium; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-16-32-7693 Received: 30 March 2019; Accepted: 23 May 2019; Published: 5 June 2019 Abstract: This review provides an overview of synthetic transformations that have been performed by both electro- and photoredox catalysis. Both toolboxes are evaluated and compared in their ability to enable said transformations. Analogies and distinctions are formulated to obtain a better understanding in both research areas. This knowledge can be used to conceptualize new methodological strategies for either of both approaches starting from the other. It was attempted to extract key components that can be used as guidelines to refine, complement and innovate these two disciplines of organic synthesis. Keywords: electrosynthesis; electrocatalysis; photocatalysis; photochemistry; electron transfer; redox catalysis; radical chemistry; organic synthesis; green chemistry 1. Introduction Both electrochemistry as well as photoredox catalysis have gone through a recent renaissance, bringing forth a whole range of both improved and new transformations previously thought impossible. In their growth, inspiration was found in older established radical chemistry, as well as from cross-pollination between the two toolboxes. In scientific discussion, photoredox catalysis and electrochemistry are often mentioned alongside each other. Nonetheless, no review has attempted a comparative evaluation of both fields in organic synthesis. Both research areas use electrons as reagents to generate open-shell radical intermediates. Because of the similar modes of action, many transformations have been translated from electrochemical to photoredox methodology and vice versa. -

The Birth of Modern Chemistry

The Birth of Modern Chemistry 3rd semester project, Fall 2008 NIB Group nr.5, House 13.2 Thomas Allan Rayner & Aiga Mackevica Supervisor: Torben Brauner Abstract Alchemy was a science practiced for more than two millennia up till the end of 18th century when it was replaced by modern chemistry, which is practiced up till this very day. The purpose of this report is to look into this shift and investigate whether this shift can be classified as a paradigm shift according to the famous philosopher Thomas Kuhn, who came up with a theory on the structure of scientific revolutions. In order to come to draw any kind of conclusions, the report summarizes and defines the criteria for what constitutes a paradigm, crisis and paradigm shift, which are all important in order to investigate the manner in which a paradigm shift occurs. The criteria are applied to the historical development of modern chemistry and alchemy as well as the transition between the two sciences. As a result, alchemy and modern chemistry satisfy the requirements and can be viewed as two different paradigms in a Kuhnian sense. However, it is debatable whether the shift from alchemy to modern chemistry can be called a paradigm shift. 2 Acknowledgments We would like to thank Torben Brauner for his guidance throughout the project period as our supervisor. We would also like to thank our opposing group – Paula Melo Paulon Hansen, Stine Hesselholt Sloth and their supervisor Ole Andersen for their advice and critique for our project. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 2. -

General Chemistry Course Description

Chemistry 110: General Chemistry Note: this is a representative syllabus for Chemistry 110. It is here for informational purposes. It is not intended to substitute for or replace the syllabus your instructor provides. Course Description: Introduction to the general principles of chemistry for students planning a professional career in chemistry, a related science, the health professions, or engineering. Stoichiometry, atomic structure, chemical bonding and geometry, thermochemistry, gases, types of chemical reactions, statistics. Weekly laboratory exercises emphasize quantitative techniques and complement the lecture material. Weekly discussion sessions focus on homework assignments and lecture material. Prerequisite: Mathematics 055 or equivalent. Previous high school chemistry not required. Taught: Annually, 5 semester credits. Course Components: Lecture, Recitation section, Laboratory Textbook: Steven S. Zumdahl and Susan A. Zumdahl, Chemistry, 5th Ed., Houghton Mifflin Company (New York, 2000). The text is available in the college bookstore. Lab Manual: Chemistry Department Faculty, Chemistry 110 Lab Manual, Fall, 2001 Edition, Kinkos. These may be purchased from Linda Noble, the Chemistry Secretary. Safety Goggles: These must be worn at all times in the laboratory. They can be purchased in the college bookstore. Calculator: Must have logs and exponential capability. Lab Notebook: This is a bound duplicate notebook with numbered pages. It can be purchased in the college bookstore Lecture Schedule 1.1-1.5 introduction, laboratory precision -

Course Syllabus

Course Syllabus Department: Science & Technology Date: January 2015 I. Course Prefix and Number: CHM 205 Course Name: Organic Chemistry I – Lecture Only Credit Hours and Contact Hours: 4 credit hours and 4 (3:0:1) contact hours Catalog Description including pre- and co-requisites: A systematic study of the chemistry of carbon compounds emphasizing reactions, mechanisms, and synthesis with a focus on functional groups, addition reactions to alkenes and alkynes, alcohols and ethers, stereochemistry, nomenclature, acid-base chemistry, reaction kinetics and thermodynamics. Completion of General Chemistry II or equivalent with a grade of C or better is prerequisite. II. Course Outcomes and Objectives Student Learning Outcomes: Upon completion of this course, the student will be able to: Demonstrate an understanding of basic principles of organic chemistry and how they relate to everyday experiences. Demonstrate problem solving and critical thinking skills Apply methods of scientific inquiry. Apply problem solving techniques to real-world problems. Demonstrate an understanding of the chemical environment and the role that organic molecules play in the natural and the synthetic world. Relationship to Academic Programs and Curriculum: This course is required for majors in chemistry, chemical engineering, biology, biotechnology, pharmacology, and other pre-professional programs. College Learning Outcomes Addressed by the Course: writing computer literacy oral communications ethics/values X reading citizenship mathematics global concerns X critical thinking information resources 1 III. Instructional Materials and Methods Types of Course Materials: A standard two-semester 200 level organic textbook and workbook. Methods of Instruction (e.g. Lecture and Seminar …): Three hours of lecture, with a one hour recitation period for individual as well as group learning activities such as case studies and guided learning activities. -

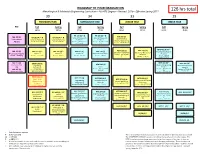

BS Metallurgical Engineering Curriculum Flowchart

ROADMAP TO YOUR GRADUATION Metallurgical & Materials Engineering Curriculum – BS MTE Degree – Revised 2016-- Effective Spring 2017 126 hrs total 30 34 33 29 FRESHMAN YEAR SOPHOMORE YEAR JUNIOR YEAR SENIOR YEAR Pre Fall SprIng Fall SprIng Fall SprIng Fall SprIng 16 hrs 14 hrs 17 hrs 17 hrs 16 hrs 17 hrs 14 hrs 15 hrs PH 105 (4) * N PH 106 (4) * N ECE 320 (3) MA 100 (3) CH 101 (4) * N CH 102 (4) * N General Physics with General Physics with Fundamentals of Intermediate General Chemistry 1 General Chemistry 2 Calculus 1 Calculus 2 Electrical Engineering Pre-reqs. = See catalog Pre-reqs. = CH 101 Pre-reqs. = MA 113 or 115 Pre-reqs. = PH 101 or 105 or Algebra Pre-reqs. = PH 106, MA 238 or 125 or 145 125 MTE 481 (4) W * AEM 250 (3) MTE 455 (4) MA 112 (3) MA 125 (4) * MA 126 (4) * MA 227 (4) MA 238 (3) Analytical Methods for Mechanics of Materials Mechanical Behavior of Precalculus Algebra Calculus 1 Calculus 2 Calculus 3 Differential Equations 1 Materials Pre-reqs. = MA 126, AEM Materials Pre-reqs. = See catalog Pre-reqs. = See catalog Pre-reqs. = MA 125 Pre-reqs. = MA 126 Pre-reqs. = MA 126 Pre-req. = MA 238 201 Pre-reqs. = AEM 250 Co-req. = MTE 441 # MA 113 (3) ENGR 103 (3) MTE 443 (3) MTE 445 (3) # AEM 201 (3) Materials Engineering Precalculus Trig Engineering Materials Engineering Statics Design 1 OR Foundations Design 2 Pre-reqs. = MA 125, PH 105, Pre-reqs. = MTE 362, 373, Pre-reqs. = MATH 125 or Pre-reqs. -

Professor of Chemistry

Bruce C. Gibb FRSC Professor of Chemistry Department of Chemistry Tulane University New Orleans, LA 70118, USA Tel: (504) 862 8136 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.gibbgroup.org Twitter: @brucecgibb Research Interests: Aqueous supramolecular chemistry: understanding how molecules interact in water: from specific ion- pairing and the hydrophobic effect, to protein aggregation pertinent to neurodegenerative disorders. Our research has primarily focused on: 1) novel hosts designed to probe the hydrophobic, Hofmeister, and Reverse Hofmeister effects, and; 2) designing supramolecular capsules as yocto-liter reaction vessels and separators. Current efforts to probe the hydrophobic and Hofmeister effects include studies of the supramolecular properties of proteins. Professional Positions: Visiting Professor, Wuhan University of Science and Technology as a Chair Professor of Chutian Scholars Program (2015-2018) Professor of Chemistry, Tulane University, New Orleans, USA (2012-present). University Research Professor, University of New Orleans, USA (2007-2011). Professor of Chemistry, University of New Orleans, USA (2005-2007). Associate Professor of Chemistry, University of New Orleans, USA (2002-2005). Assistant Professor of Chemistry, University of New Orleans, USA, (1996-2002). Education: Postdoctoral Work Department of Chemistry, New York University. Synthesis of Carbonic Anhydrase (CA) mimics with Advisor: Prof. J. W. Canary, (1994-1996). Department of Chemistry, University of British Columbia, Canada De Novo Protein development. Advisor: Prof. J. C. Sherman (1993-1994). Ph.D. Robert Gordon’s University, Aberdeen, UK. Synthesis and Structural Examination of 3a,5-cyclo-5a- Androstane Steroids. Advisors: Dr. Philip J. Cox and Dr. Steven MacManus (1987-92) . B.Sc. with Honors in Physical Sciences Robert Gordon’s University, Aberdeen, UK. -

Chemistry (CH) 1

Chemistry (CH) 1 Chemistry (CH) CH 101 - INTRO TO CHEMISTRY Semester Hours: 3 Properties of solids, liquids, gases, and solutions, atomic theory and bonding, concentration concepts, and physical and chemical properties of the more common elements and their compounds. No placement examination is required. Prerequisite: MA 110 or prerequisites with concurrency MA 112 or higher and CH 105. CH 101R - RECITATION Semester Hours: 0 CH 105 - INTRO CHEMISTRY LAB Semester Hour: 1 Complements the lecture material for CH 101. Laboratory fundamentals and basic chemical principles. Prerequisite with concurrency: CH 101. CH 121 - GENERAL CHEMISTRY I Semester Hours: 3 For science and engineering majors. Chemical properties of elements, their periodic groups, and their compounds. Reactions and stoichiometry. Nature of the chemical bond, molecular structure, thermochemistry. Properties of gases, liquids, and solids. Prerequisite: CH 101 or placement test. Prerequisites with concurrency: MA 113 or higher, and CH 125. CH 121M - GENERAL CHEMISTRY FOR CHEMISTS Semester Hours: 3 For Chemistry Majors and Minors. Chemical properties of elements and the Periodic Table. Reactions and stoichiometry. Nature of chemical bonds, molecular structure, thermochemistry. Properties of gases, liquids, and solids. Intro to your exciting Department and its programs. Engagement activities. Prerequisites: CH 101 or Placement. Prerequisites with concurrency: MA 113 or higher, CH 125. CH 121R - RECITATION Semester Hours: 0 CH 122 - GENERAL CHEMISTRY ENGINEERS Semester Hours: 3 This course is designed as a one semester presentation of key aspects in general chemistry and is recommended for all engineering majors except chemical engineers. Covers topic on atoms and molecules: reactions and stoichiometry; gases; the periodic table; atomic structure, chemical bonding and molecular structure; materials; energy, entropy, and free energy; kinetics and equilibrium; and electrochemistry. -

Stoichiometry of Chemical Reactions 175

Chapter 4 Stoichiometry of Chemical Reactions 175 Chapter 4 Stoichiometry of Chemical Reactions Figure 4.1 Many modern rocket fuels are solid mixtures of substances combined in carefully measured amounts and ignited to yield a thrust-generating chemical reaction. (credit: modification of work by NASA) Chapter Outline 4.1 Writing and Balancing Chemical Equations 4.2 Classifying Chemical Reactions 4.3 Reaction Stoichiometry 4.4 Reaction Yields 4.5 Quantitative Chemical Analysis Introduction Solid-fuel rockets are a central feature in the world’s space exploration programs, including the new Space Launch System being developed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to replace the retired Space Shuttle fleet (Figure 4.1). The engines of these rockets rely on carefully prepared solid mixtures of chemicals combined in precisely measured amounts. Igniting the mixture initiates a vigorous chemical reaction that rapidly generates large amounts of gaseous products. These gases are ejected from the rocket engine through its nozzle, providing the thrust needed to propel heavy payloads into space. Both the nature of this chemical reaction and the relationships between the amounts of the substances being consumed and produced by the reaction are critically important considerations that determine the success of the technology. This chapter will describe how to symbolize chemical reactions using chemical equations, how to classify some common chemical reactions by identifying patterns of reactivity, and how to determine the quantitative relations between the amounts of substances involved in chemical reactions—that is, the reaction stoichiometry. 176 Chapter 4 Stoichiometry of Chemical Reactions 4.1 Writing and Balancing Chemical Equations By the end of this section, you will be able to: • Derive chemical equations from narrative descriptions of chemical reactions.