Are State Constitutional Conventions Things of the Past? the Ncri Easing Role of the Constitutional Commission in State Constitutional Change Robert F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nazis Burn, Synagogues and Loot German Jews' Stores

Maabar of the Aadit Buiean at Ctmlatleni MANCHESTER — A CITY OP VILLAGE (HARM VOL. Lvni., NO. 85 tUa a a tflsd A dv e rtM a g on F age 19) MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 10,1988 (TWELVE PAGES) Two Die as Army Plane Crashes in Street REPUBLICANS GAIN NAZIS BURN, 11 GOVERNORSHIPS; SYNAGOGUES AND LOOT 78 ADDED IN HOUSE SPANIELS NEEDN'T GET Torn From Coontiiig Of Bal-1 TIBEO DRAGGING EABS j GERMAN JEWS’ STORES Washington, Nov. 10.—(AP)— I lots With Avowed Inten- No cocker spaniel need get Ured BANDITS GET 38 BAGS dragging bia ears around any - ’ OF CANCELLED CHECBS more. Indulge h Greateit Wiy i ' tioB Of Trying To Take LEADERS RAP A patent was Issued today to Phllsdelphls, Nov. 10.—(AP)_ Ruth F. McCalee of Evanston, Six bsndiU armed with a sub- Of Violence Since ffider Over Prendency In 1 94 0.1 m., for a . pair of pockets to ACnON TAKEN machine glut, shotguns and revol- hang over the dog’s bead and vers held up s Railway Express carry his ears for him Ajnncy, Inc., truck driver and his Came To Power h Ni* hwpe'.er at--------- a mid-city- — station• early By ASSOCIATED PBESS ONPAUSTINE toda}^ and fled in an automobile. ^ The Democratic u d Republican their loot was 26 bs,gs of can- tional Day Of Vengeance ’parties b^an a two-year atruggle celled checks. for power today as the aftermath Arabs And Jews Alike Bit- For Asassination if Dip- 'tS political upheavals in Tuesday’s HACKEH, STATE electlona. -

Filling Vacancies in the Office of Lieutenant Governor

MAY 2009 CITIZENS UNION | ISSUE BRIEF AND POSITION STATEMENT Filling Vacancies in the Office of Lieutenant Governor INTRODUCTION Citizens Union of the City of Shortly after Citizens Union’s last report on the subject of filling vacancies in February 2008, New York is an independent, former Governor Eliot Spitzer resigned from the office of governor and former Lieutenant non-partisan civic organization of Governor David A. Paterson assumed the role of New York’s fifty-fifth governor. Although the members dedicated to promoting good government and political reform in the voters elected Paterson as lieutenant governor in 2006, purposefully to fill such a vacancy in the city and state of New York. For more office of governor should it occur, his succession created a vacancy in the office of lieutenant than a century, Citizens Union has governor, and, more importantly, created confusion among citizens and elected officials in served as a watchdog for the public Albany about whether the current Temporary President of the Senate who serves as acting interest and an advocate for the Lieutenant Governor can serve in both positions simultaneously. This unexpected vacancy common good. Founded in 1897 to fight the corruption of Tammany Hall, exposed a deficiency in the law because no process exists to fill permanently a vacancy in the Citizens Union currently works to position of lieutenant governor until the next statewide election in 2010. ensure fair elections, clean campaigns, and open, effective government that is Though the processes for filling vacancies ordinarily receive little attention, the recent number accountable to the citizens of New of vacancies in various offices at the state and local level has increased the public’s interest in York. -

1S 1/'Jn JI R 2 5 --04,2 G O'f-- L/O Fil [- 2 GEB/Fm

ccn1rv1L ~cG1str;j (/20-3Y-2) SG- Heo.dGUarir;.r<,S p10.nn1n~--G-1f2iS f-'.orpuww.V1eri7"" j-Jta.dqr:AarTe,S- ?b ,YlFJKCii f 1 '1? rn OY1 //i WI er11S' 1S 1/'Jn JI r 2 5 --04,2 G o'f-- l/o Fil [- 2 GEB/fm I • • ' dexed.-,, ,--·-•• 25 J anuary 1952 I ~ Dear Clark, Now that. I am back from -Paris I think we ought to have a meeting so e day soon to talk about the fountain; that is, the possible construction schedule, the financial report, and the arrangements tor dedicat ion. Yours sincerely, Glenn • ett Executive Offi cer Headquarters Planning Offi-ce \ .... '\ ' '\ ) \ I~ , ' \ ir. , Clark Eichelberger, Director American Association tor t he United Nations ..·1 , -./ \' / 45 st 65th Street New York 21, n.Y. \ '\ ' .. co_0\1\1\ J -r-r E CE rl JJtf\L FOU 1\ I -r;\ 1rl ;-\ -r , , , 1\ '), (' u ,, t'J-r j t:, c: lJ1\I I TED r ..C.. r\ V --::J . r\ h ..Ch. J Newsletter No. Northwest Headquarters A AUN January 1 22 909 Fourth Ave,, Seattle 4, Wash. 1 9 5 2 This is to wish you HAPPY NEW YEAR and to remind you of 1. the dedication date of FREEDOM FOUNTAIN during the week of June 15-21, 1952; 2. the need of a replica of your state seal for the dedication plaque; J, the necessity of all states completing their share of the project at the earliest possible date. to give you the reports on CaLifornia, Ohio, and New Jersey (attached). -

Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletins the Roosevelt Wild Life Station

SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Digital Commons @ ESF Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletins The Roosevelt Wild Life Station 1939 Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin Ralph T. King SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/rwlsbulletin Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation King, Ralph T., "Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin" (1939). Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletins. 10. https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/rwlsbulletin/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The Roosevelt Wild Life Station at Digital Commons @ ESF. It has been accepted for inclusion in Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletins by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ESF. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Bulletin of the New York State Vol. XII. No. 2 College of Forestry at Syracuse University October, 1939 THE ECOLOGY AND ECONOMICS OF THE BIRDS ALONG THE NORTHERN BOUNDARY OF NEW YORK STATE By A. Sidney Hyde Roosevelt Wildlife Bulletin VOLUME 7 NUMBER 2 Published by the Roosevelt Wildlife Forest Experiment Station at the New York State College of Forestry, Syracuse, N. Y. SAMUEL N. SPRING. Dean . CONTENTS OF RECENT ROOSEVELT WIUDLIFE BULLETINS AND ANNALS BULLETINS Roosevelt Wildlife Bulletin, Vol. 4, No. i. October, 1926. 1. The Relation of Birds to Woodlots in New York State Waldo L. McAtee 2. Current Station Notes Charles C. Adams (Out of print) Roosevelt Wildlife Bulletin, Vol. 4, No. 2. June, 1927. 1. The Predatory and Fur-bearing Animals of the Yellowstone National Park Milton P. -

Download Full Book

Neighbors in Conflict Bayor, Ronald H. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Bayor, Ronald H. Neighbors in Conflict: The Irish, Germans, Jews, and Italians of New York City, 1929-1941. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.67077. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/67077 [ Access provided at 27 Sep 2021 07:22 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. HOPKINS OPEN PUBLISHING ENCORE EDITIONS Ronald H. Bayor Neighbors in Conflict The Irish, Germans, Jews, and Italians of New York City, 1929–1941 Open access edition supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. © 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press Published 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. CC BY-NC-ND ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-2990-8 (open access) ISBN-10: 1-4214-2990-X (open access) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3062-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3062-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3102-4 (electronic) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3102-5 (electronic) This page supersedes the copyright page included in the original publication of this work. NEIGHBORS IN CONFLICT THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY STUDIES IN HISTORICAL AND POLITICAL SCIENCE NINETY-SIXTH SEMES (1978) 1. -

Newyork Power Authority

1633 Broadway New York, New York 10019 212 468.6000 NewYork Power Authority November 16, 1999 Ms. Debra Renner Acting Secretary NYS Public Service Commission 3 Empire State Plaza, 14th Floor Albany, NY 12223 Subject: Pre-Application Report Proposed Combined Cycle Facility New York Power Authority Dear Ms. Renner: The New York Power Authority, which supplies low cost electricity for the subways, schools, hospitals and other public facilities in New York City as well as for businesses throughout the metropolitan area, has filed a Pre-Application Report with the New York State Public Service Commission (NYSPSC). Enclosed for your review and comment is a copy of the Pre-Application Report. This is the first step in the permitting process for a proposed combined cycle facility in Astoria, Queens. The purpose of the report is to initiate formal consultation as described in Section 163 of the Public Service Law and Section 1000.4 of the Public Service Commission's Regulations (6NYCRR, Section 1000.4) with the New York State Department of Public Service, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, other involved agencies and the public regarding the scope of studies to be conducted in support of a future application by the New York Power Authority to the Siting Board on Electic Generation Siting and the Environment in accordance with Article X of the New York State Public Service Law. If you have any comments on the Pre-Application Report you are requested to submit them in writing within thirty days (date) to: Ms. Ellen Koivisto Licensing Manager New York Power Authority 1633 Broadway New York, NY 10019 If you have any questions on the attached, please contact me at 212-468-6751. -

Full Article

2219 BOPST & GALIE (SP) 9/8/2013 10:36 AM ―IT AIN‘T NECESSARILY SO‖: THE GOVERNOR‘S ―MESSAGE OF NECESSITY‖ AND THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS IN NEW YORK Peter J. Galie* & Christopher Bopst** I think the people of the state said they want something done and they want it done now . Let‘s act.1 —Governor Andrew Cuomo The bill was muscled through with disturbing speed after days of secret negotiations and a late-night vote Monday by state senators who had barely read the complicated measure before passing it.2 —The New York Times ************************************************************* Three days of debate, everyone has an opinion, it‘s entirely transparent, [and] we never reach resolution . I get 100 percent for transparency. I get zero for results.3 —Governor Andrew Cuomo A legislature that rushes critical, controversial bills to passage is one that deliberately excludes the public. A legislature that cannot wait three days to revise a mission statement governs by crisis. This must stop.4 —Syracuse Post Standard ************************************************************* * Professor Emeritus, Canisius College, Buffalo, New York. ** Partner, Goldberg Segalla LLP, Buffalo, New York. The authors would like to thank John Drexelius, former chief legislative aide to retired State Senator Dale M. Volker, for helping them to understand the political ―ins and outs‖ of the message of necessity. 1 Critics Assail Cuomo‘s Gun Deal as Secret, Rushed, DAILY GAZETTE, http://www.dailygazette.com/news/2013/jan/15/0115_rushed (last updated Jan. 15, 2013, 5:40 PM) [hereinafter Critics Assail]. 2 Editorial, New York Leads on Gun Control, N.Y. TIMES, Jan. 16, 2013, at A22. -

Canned Goods to Be Put on Ration List

. H ' ' / ■ iX lU B Tl E H SATURDAT, DECEMBER 26.1942 Stirafna H^niQ Avengs Dsfly Ciretlation Ths W6Bthsr Wat Bw Moath ef Nevnaher, 1943 Fonoant o f C. B. WenthM The Armory Lunchroom pur chased in October by Howard Lt. Gordon T. Weir 7,814 About Town Is Decorated Bain tonight with fi ruing mhi Hasting from Joseph Zapatka has Heard Along Main Street Andtt again changed hands. Mr. Hast Gains Promotion SPECIAL la BerInhIrM; Uttto change In ings has sold ths business to for Bravery tompemtam _________; (J. a.) md U n . Stn- George Pearl. And on Some of Manche$ter*$ Side Strieets, Too A DAYS ONLY — DECEMBER 28th - 31st. Manchester—‘A City of Village Charm I IX KoUhmb wbo taav* racmUy to BostOR, ifMnt Chrlatmu Second Lieut. Gordon T. Weir, 23, son of Mr. and Mrs. TbomaA Capt. W. S. George, Jr., tM r pucnta, Mr. and Mrs. VOL. LXIL, NO. 74 (OInnBSeS AdvertMag am Pago 16) MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, DECEMBER 28,1942 (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS m C, ItoUnaon and Mr. and Weir, of 117 Summer street, hiss Now that the poeUnastershlp in-i natives. He was one of those as Men’s Trousers or Ladies’ Slack Bolin Selected" Is Awarded Purple town has been settled it can be sisting in the mall distribution. IMMrt Lb Ooopar. llisy left been promoted to the gnuM of M cnlng forMtsslssippl. where Heart; The Citation. stated without fear of much con Robinson will assume Head of Lodge first lieutenant at the Bljfuevllle tradiction that civil service Inves We note in the news that Ger Army Air Field. -

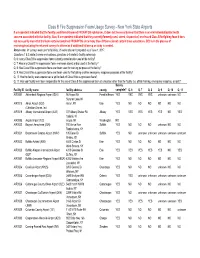

Class B Fire Suppression Foam Usage Survey

Class B Fire Suppression Foam Usage Survey - New York State Airports If a respondent indicated that the facility used/stored/disposed PFOA/PFOS substances, it does not necessarily mean that there is an environmental/public health concern associated with that facility. Also, if a respondent indicated that they currently/formerly used, stored, disposed of, or released Class B firefighting foam it does not necessarily mean that the foam contains/contained PFOA/PFOS since many Class B foams do not contain these substances. DEC is in the process of reviewing/evaluating the returned surveys to determine if additional follow-up or study is needed. Return rate: 91 surveys were sent to facilities; 90 were returned completed as of June 1, 2017. Questions 1 & 2 relate to name and address; questions 3-5 relate to facility ownership. Q. 6: Is any Class B fire suppression foam currently stored and/or used at the facility? Q. 7: Has any Class B fire suppression foam ever been stored and/or used at the facility? Q. 8: Has Class B fire suppression foam ever been used for training purposes at the facility? Q. 9: Has Class B fire suppression foam ever been used for firefighting or other emergency response purposes at the facility? Q. 10: Has the facility ever experienced a spill or leak of Class B fire suppression foam? Q. 11: Has your facility ever been responsible for the use of Class B fire suppression foam at a location other than the facility (i.e. offsite training, emergency response, or spill)? Survey Facility ID facility name facility address county complete? Q. -

The Human Right to Health Care Under the New York State Constitution

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 35 Number 3 Article 2 2008 Positive Health: The Human Right to Health Care Under the New York State Constitution Alan Jenkins The Opportunity Agenda Sabrineh Ardalan Third Circuit Court of Appeals Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Alan Jenkins and Sabrineh Ardalan, Positive Health: The Human Right to Health Care Under the New York State Constitution, 35 Fordham Urb. L.J. 479 (2008). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol35/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POSITIVE HEALTH: THE HUMAN RIGHT TO HEALTH CARE UNDER THE NEW YORK STATE CONSTITUTION Alan Jenkins* & Sabrineh Ardalan** I. INTRODUCTION In his first State of the State address, former New York Gover- nor Eliot Spitzer recognized the urgent need to "reform our health care system."1 He explained that "when 2.8 million New Yorkers can't afford health insurance, that affects not only them and their families, it affects everyone," and promised to take steps to make health care more affordable and accessible to all New Yorkers.2 As the governor recognized, access to quality health care is es- sential to realizing our full potential as individuals, families, com- munities, and as a society. -

Pre-Filed Hearing Exhibit NYS000093, NYPA, NYPA to Cease Operations

NYP A to Cease Operations of Queens Power Plant on January 31 st http://www.nypa.gov/press/20l0/l00l29a.html .{11 ~ll~ ~l ~lllll~l~~ ~l~;~::· j1l1l1~~lli~lf~l::~1}li\l~i~Jj~r:~l1~t: :lr~~;~~l~J~lf~j:t}:m( :::t~ll~l1l~1~~@1~11r ~!;n?:'~!rroutfilliidOCiiEiY NEWS NYPA to Cease Operations of Queens Power Plant on January 31st Contact: Bert Cunningham 914-390-8160 January 29, 2010 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ASTORIA - The New York Power Authority (NYPA) today announced that it will permanently cease operations of an 885-Megawatt (MW) generating unit at the Charles Poletti Power Project at 11 :59 PM on January 31, 2010, in accordance with an agreement announced in September, 2002. The natural gas- and oil-fueled generating unit began commercial operation in March, 1977. It has been operating since September, 2002 under the terms of a joint agreement with the State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), the City of New York, the Borough of Queens and other interested parties that curtailed its output to limit emissions. The joint agreement also stipulated that the plant must cease operations no later than January 31 st of this year. In return for agreeing to cease operations, NYPA's state licensing application to build and operate a new 500-MW, combined-cycle, natural gas-fired power plant at the Poletti site received the support of the city, the surrounding community, and various interested parties. The 500-MW facility began commercial operation in December, 2005, helping the Power Authority to meet the electricity requirements of its governmental customers in New York City and the thousands of public facilities they operate. -

New York State History

GOVERNORS OF NEW YORK David B. Hill, January 6, 1885 (Date ELECTED TO OFFICE follows the name) Lieutenant Governor, became Governor upon resignation of Cleveland in 1885; subsequently elected to two full terms, on George Clinton, July 9, 1777 November 3, 1885 and November 6, 1888. The Constitution of 1777 did not specify when the Governor Roswell P. Flower, November 3, 1891 should enter on the duties of his office. Governor Clinton Levi P. Morton, November 6, 1894 was declared elected on July 9 and qualified on July 30. Frank S. Black, November 3, 1896 On February 13, 1787, an act was passed for regulating Theodore Roosevelt, November 8, 1898 elections. It also provided that the Governor and Lieutenant Benj. B. Odell, Jr., November 6, 1900 and November 4, 1902 Governor should enter on the duties of their respective office Frank W. Higgins, November 8, 1904 on July 1 after their election. Charles E. Hughes, November 6, 1906 and November 3, 1908 New York John Jay, April 1795 Appointed Justice of the United States Supreme Court and George Clinton, April 1801 resigned the office of Governor on October 6, 1910. Morgan Lewis, April 1804 Horace White, October 6, 1910 State Daniel D. Tompkins, April 1807 Lieutenant Governor, became Governor upon resignation John Taylor, March 1817 of Hughes. History Lieutenant Governor, Acting Governor John A. Dix, November 8, 1910 De Witt Clinton, July 1, 1817 William Sulzer, November 5, 1912 Joseph C. Yates, November 6, 1822 Martin H. Glynn, October 17, 1913 New Yorkers are rightfully proud of The Constitution of 1821 provided that the Governor and Succeeded Sulzer, who was removed from office.