Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Composers and the Red Courtiers: Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930S

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa marraskuun 24. päivänä 2007 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in the Building Villa Rana, Blomstedt Hall, on November 24, 2007 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Seppo Zetterberg Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:9789513930158 ISBN 978-951-39-3015-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-2990-9 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Mikkonen, Simo State composers and the red courtiers. -

The Public Discussion of the 1936 Constitution and the Practice of Soviet Democracy

Speaking Out: The Public Discussion of the 1936 Constitution and the Practice of Soviet Democracy By Samantha Lomb B.A. in History, Shepherd University, 2006 M.A. in History, University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 University of Pittsburgh Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Samantha Lomb It was defended on April 7, 2014 and approved by William Chase, PhD, Professor Larry E. Holmes, PhD, Professor Emeritus Evelyn Rawski, PhD, Professor Gregor Thum, PhD, Assistant Professor Dissertation Director: William Chase, PhD, Professor ii Copyright © by Samantha Lomb 2014 iii Speaking Out: The Public Discussion of the 1936 Constitution and the Practice of Soviet Democracy Samantha Lomb, PhD University of Pittsburgh 2014 The Stalinist Constitution was a social contract between the state and its citizens. The Central leadership expressly formulated the 1936 draft to redefine citizenship and the rights it entailed, focusing on the inclusion of former class enemies and the expansion of “soviet democracy”. The discussion of the draft was conducted in such a manner as to be all-inclusive and promote the leadership’s definition of soviet democracy. However the issues that the leadership considered paramount and the issues that the populace considered paramount were very different. They focused on issues of local and daily importance and upon fairness and traditional peasant values as opposed to the state’s focus with the work and sacrifice of building socialism. -

Mccauley Stalinism the Thirties.Pdf

Stalin and Stalinism SECOND EDITION MARTIN McCAULEY NNN w LONGMANLONDON AND NEW YORK The Thirties 25 and October 1929, and Stalin declared on 7 November 1929 that the great PART TWO: DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS 2 THE movement towards collectivisation was under way [8]. The Politburo stated on 5 January 1930 that large-scale kulak production was to be replaced by large- scale kolkhoz production. Ominously, for the better-off farmers it also proclaimed the THIRTIES ‘liquidation of the kulaks as a class*. It was hoped that the collectivisation of the key grain-growing areas, the North Caucasus and the Volga region, would be completed by the spring of 1931 at the latest and the other grain-growing areas by the spring of 1932. A vital role in rapid collectivisation was played by the 25,000 workers who descended on the countryside to aid the ‘voluntary* process. The ‘twenty-five thousanders*, as they were called, brooked no opposition. They were all vying with one another for the approbation of the party. Officially, force was only permissible against kulaks, but the middle and poor peasants were soon sucked into the maelstrom of violence. Kulaks were expelled from their holdings and their POLITICS AND THE ECONOMY stock and implements handed over to the kolkboz. What was to become of them? Stalin was brutally frank: ‘It is ridiculous and foolish to talk at length After the war scare of 1927 [5] came the fear of foreign economic intervention. about dekulakisation. ... When the head is off, one does not grieve for the hair. Wrecking was taking place in several industries and crises had occurred in There is another question no less ridiculous: whether kulaks should be allowed to join the collective farms? Of course not, others — or so Stalin claimed in April 1928. -

Number 167 Draft: Not for Citation Without Permission

DRAFT: NOT FOR CITATION WITHOUT PERMISSION OF AUTHOR NUMBER 167 POLITICS OF SOVIET INDUSTRIALIZATION: VESENKHA AND ITS RELATIONSHIP WITH RABKRIN, 1929-30 by Sheila Fitzpatrick Fellow, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies Colloquium Paper December, 1983 Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Washington, D.C. -1- The historical study of Soviet politics has its peculia rities. Dealing with the 1920s, Western historians have generally studied factional politics - Lenin and Stalin versus the oppositions • or the manipulation of the party apparatus that brought Stalin to power. Soviet historians have also concentrated heavily on the factional struggles, admittedly from a somewhat different perspective. In addition, they often write histories of particular government institutions (Sovnarkom, Rabkrin and the like) that rather resemble commissioned company histories in their avoidance of the scandalous, dramatic and political aspects of their theme. Reaching the 1930s, both Western and Soviet historians have a tendency to throw up their hands and retire from the fray. Western historians run out of factions to write about. There is a memoir literature on the purges and a rather schematic scholarly literature on political control mechanisms, but the Stalin biography emerges as the basic genre of political history. For Soviet historians, the subject of the purges is taboo except for a few risqu~ paragraphs in memoirs, and even biographies of Stalin are not possible. There are no more institutional histories, and the safest (though extremely boring} topic is the 1936 Constitution. The peculiarity of the situation lies in the neglect of many of the staples of political history as practised outside -2- the Soviet field, notably studies of bureaucratic and regional politics and local political histories. -

THE GENES of HYENAS Second Revised Edition

Arif Mansourov THE GENES OF HYENAS Second Revised Edition BAKU 1994 1 Translated into English by Zia K. Neymatoulin A. Mansourov "The Genes of Hyenas" B. Sharg-Garb, 1994, 80 p. The names of those acting in this play-pamphlet are, beyond any doubt, well-known to the readers. The pro-armenian intrigues and plots carried on by its heroes against the Azerbaijani people at different times are not the author's artistic invention, but real historical facts based on documents It is very likely that having read this small-volume play-pamphlet, the reader may find it not difficult to rightly guess who pursued, when and what kind of policy against us, and probably will draw for himself an appropriate conclusion. ISBN 5-565-00135-8 © Sharg-Garb, 1994 2 The author of this play-pamphlet is Arif Enver ogly Mansourov, one of the renowned public figures, representatives of intelligentsia, who enjoys well-deserved respect and authority in our republic. While holding important managerial and public offices, he, at the same time, is actively involved in scientific, social and political journalism. He is the author of ten scientific works, as well as the book "White Spots of History and Peristroika" which was published in several languages and had a wide public response in the republic and far beyond its borders, as also of many splendid articles on social and political affairs which were taken in by the readers with great interest. Remaining true to the noble traditions of his ancestors, Arif Mansourov, one may say, occupies the first place among contemporary patrons of art in the republic. -

Copyright 2012 Maria Galmarini

Copyright 2012 Maria Galmarini THE “RIGHT TO BE HELPED”: WELFARE POLICIES AND NOTIONS OF RIGHTS AT THE MARGINS OF SOVIET SOCIETY, 1917-1950 BY MARIA GALMARINI DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Diane Koenker, Chair Professor Mark Steinberg Professor John Randolph Professor Antoinette Burton ii Abstract In this dissertation, I trace the course of ethically founded notions of rights in the Soviet experience from 1917 to 1950, focusing on the “right to be helped” as the entitlement to state assistance felt by four marginalized social groups. Through an analysis of the requests for help written by social activists on behalf of disabled children, blind and deaf adults, single mothers, and political prisoners, I examine the multiple and changing ideas that underlie the defense of this right. I reveal that both the Soviet state authorities and these marginalized social groups tended to reject charity as a form of unwanted condescension. In addition, state organs as well as petitioners applied legal notions of rights arbitrarily and situationally. However, political leaders, social activists, and marginalized citizens themselves engaged in dialogues that ultimately produced a strong, ethically grounded consciousness of rights. What I call “the right to be helped” was a framework of concepts, practices, and feelings that set the terms for what marginalized individuals could imagine and argue in relation to state assistance. As such, the right to be helped fundamentally reflected Soviet understandings of disability, generation, gender, labor merits, and human suffering. -

We Shall Refashion Life on Earth! the Political Culture of the Young Communist

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles We Shall Refashion Life on Earth! The Political Culture of the Young Communist League, 1918-1928 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Sean Christopher Guillory 2009 © Copyright by Sean Christopher Guillory 2009 To Rodney, Roderick, Dianne, and Maya iii Table of Contents Acknowledgements v Vita viii Abstract x Introduction: What is the Komsomol? 1 Chapter 1 “We were not heroes. Our times were heroic” 44 Chapter 2: “Are you a komsomol? Member of the party? Our guy!” 88 Chapter 3: “He’s one of the guys and if he wants three wives that’s his business.” 131 Chapter 4: “Activists are a special element” 190 Chapter 5: “The right to punish and pardon - like God judges the soul” 246 Chapter 6: “A New Voluntary Movement” 292 Conclusion “Youth it was that led us” 345 Bibliography 356 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Intellectual work is always a collective effort, and the study before the reader is no exception. Several institutions and individuals provided direct or indirect financial assistance, scholarly advice, intellectual influence, and moral and emotional support in this long journey. I would like to thank the History Departments at UC Riverside and UCLA, the UCLA Graduate Division, the UCLA Center for European and Eurasian Studies for academic and financial support. Research for this project was provided by the generous funding from the United States Department of Education through the Fulbright- Hays Program. I wish to thank the archivists in Russia for their patience and aid in finding materials for this study. -

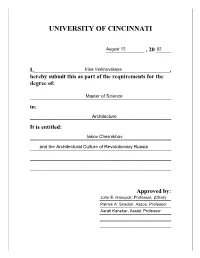

Iakov Chernikhov and His Time

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ IAKOV CHERNIKHOV AND THE ARCHITECTURAL CULTURE OF REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE in the School of Architecture and Interior Design of the college of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning 2002 by Irina Verkhovskaya Diploma in Architecture, Moscow Architectural Institute, Moscow, Russia 1999 Committee: John E. Hancock, Professor, M.Arch, Committee Chair Patrick A. Snadon, Associate Professor, Ph.D. Aarati Kanekar, Assistant Professor, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The subject of this research is the Constructivist movement that appeared in Soviet Russia in the 1920s. I will pursue the investigation by analyzing the work of the architect Iakov Chernikhov. About fifty public and industrial developments were built according to his designs during the 1920s and 1930s -

Caffeinated Avant-Garde: Futurism During the Russian Civil War 1917-1921

Australian Journal of Politics and History: Volume 58, Number 3, 2012, pp. 353-366. Caffeinated Avant-Garde: Futurism During the Russian Civil War 1917-1921 IVA GLISIC University of Western Australia Scholarship on Russian Futurism often interprets this avant-garde movement as an essentially utopian project, unrealistic in its visions of future Soviet society and naïve in its comprehension of the Bolshevik political agenda. This article questions such interpretations by demonstrating that the activities of Russian Futurists during the Civil War period represented a measured response to what was a challenging contemporary socio-political reality. By examining the development of Futurist ideology through this period, considering first-hand Futurist descriptions of dealing with the fledgling Soviet system, and recalling Slavoj Žižek’s interpretations of revolution and utopianism, a different image of the Futurist project emerges. Futurism, indeed, was a movement far more aware of the intricacies of its historical period than has previously been recognised. Vladimir Mayakovsky on How the Soviet System Works In 1919, on 19 September, the famous Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky sat down to pen a letter — a letter that he did not want to write.1 The problem, and the reason for Mayakovsky’s chagrin, was that the letter in question was to be addressed to someone working within that most famous of amorphous voids: the Soviet bureaucracy. Though ostensibly seeking payment — after several failed first-hand attempts — for work he had been commissioned to produce, Mayakovsky’s letter quickly grew into something else altogether, as he expressed his frustration and concern with the convoluted nature of the fledgling Soviet administration. -

SOVIET FORDISM in PRACTICE – Building and Operating the Soviet River

SOVIET FORDISM IN PRACTICE – Building and operating the Soviet River Rouge, 1927-1945 The technical processes and production methods of Ford’s factory should form the basis of Avtostroi’s planning. – Stepan Dybets, 19301 Giancarlo Camerana was secretary of the Fiat board of directors and second- in-command at the Italian carmaker when he made his first trip to the United States in September 1936. His destination was Detroit, where Charles Sorensen, head of operations at Ford Motor Company, received him personally and showed him around the Rouge factory. At the time of Camerana’s voyage, Fiat was projecting the construction of a new production complex at Mirafiori. The new factory’s layout was to be based on River Rouge.2 One month later, in October 1936, Ferdinand Porsche was in Detroit. The engineer-in-chief of the Nazi Volkswagen plant, then in the planning phase, visited Ford Motor Company to keep abreast with the latest American production technology. The new German factory, after all, was to be modeled on River Rouge.3 After traveling on to New York, Camerana paid the obligatory homage to Sorensen (“I am speechless in admiration of the Ford factories and organization”) before asking for advice. How could the new plant at Mirafiori most 1 TsANO (Central Archive of the Nizhnii Novgorod Oblast’), f. 2431, o.4, d.11a, l. 21. 2 Camerana to Sorensen, 28 Sep 1936, BFRC, Acc. 38, Box 80. Duccio Bigazzi, La Grande Fabbrica. Organizzazione Industriale E Modelo Americano Alla Fiat Dal Lingotto a Mirafiori (Milano: Feltrinelli, 2000), 73-75. 3 Ghislaine Kaes, “Vortrag über die Nordamerikareise des Herrn Dr. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents • Abbreviations & General Notes 2 - 3 • Photographs: Flat Box Index 4 • Flat Box 1- 43 5 - 61 Description of Content • Lever Arch Files Index 62 • Lever Arch File 1- 16 63 - 100 Description of Content • Slide Box 1- 7 101 - 117 Description of Content • Photographs in Index Box 1 - 6 118 - 122 • Index Box Description of Content • Framed Photographs 123 - 124 Description of Content • Other 125 Description of Content • Publications and Articles Box 126 Description of Content Second Accession – June 2008 (additional Catherine Cooke visual material found in UL) • Flat Box 44-56 129-136 Description of Content • Postcard Box 1-6 137-156 Description of Content • Unboxed Items 158 Description of Material Abbreviations & General Notes, 2 Abbreviations & General Notes People MG = MOISEI GINZBURG NAM = MILIUTIN AMR = RODCHENKO FS = FEDOR SHEKHTEL’ AVS = SHCHUSEV VNS = SEMIONOV VET = TATLIN GWC = Gillian Wise CIOBOTARU PE= Peter EISENMANN WW= WALCOT Publications • CA- Современная Архитектура, Sovremennaia Arkhitektura • Kom.Delo – Коммунальное Дело, Kommunal’noe Delo • Tekh. Stroi. Prom- Техника Строительство и Промышленность, Tekhnika Stroitel’stvo i Promyshlennost’ • KomKh- Коммунальное Хозяство, Kommunal’noe Khoziastvo • VKKh- • StrP- Строительная Промышленность, Stroitel’naia Promyshlennost’ • StrM- Строительство Москвы, Stroitel’stvo Moskvy • AJ- The Architect’s Journal • СоРеГор- За Социалистическую Реконструкцию Городов, SoReGor • PSG- Планировка и строительство городов • BD- Building Design • Khan-Mag book- Khan-Magomedov’s -

From Inzhener to ITR: Russian Engineers and the First Five-Year

From Inzhener to ITR: Russian Engineers and the First Five-Year Plan A Thesis Submitted To the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By John Vidumsky January, 2011 Approvals: Dr. Vladislav Zubok, Department of History Dr. Jay Lockenour, Department of history i ABSTRACT The Russian engineering corps was almost completely transformed during the first five-year plan, which ran from 1928-1932. The purpose of this thesis is to examine the nature of that change, and the forces that drove it. In this paper, I will argue that the corps was transformed in four fundamental ways: class composition, skill level, role in production, and political orientation. This paper begins by examining the old engineering corps on the eve of the first five year plan. Specifically, it examines Russian engineers as a subgroup of the intelligentsia, and how that problematized their relationship with power. I next examine how the Soviet government forcibly reshaped the engineering corps by pressure from above, specifically by a combination of state terror and worker-promotion campaigns. These two phenomena were closely intertwined. Along with collectivization and crash industrialization, they were part of the “Cultural Revolution” that reshaped Russian society in this period. I next examine how the campaign of terror against engineers was used by Stalin and his camp for political gain on a variety of fronts. Lastly, I will examine how engineers became part of the Soviet elite after 1931. For sources, I rely especially on the correspondence between Stalin, Kaganovich, and Molotov, which was published in the Yale University Annals of Communism series.