'King John's Irish REX Coinage Revisited. Part II: the Symbolism Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval French Alexander: Arthurian Orientalism, Cross-Cultural Contact, and Transcultural Assimilation in Chrétien De Troyes’S Cligés

Otterbein University Digital Commons @ Otterbein Modern Languages & Cultures Faculty Scholarship Modern Languages & Cultures 2013 The »Other« Medieval French Alexander: Arthurian Orientalism, Cross-Cultural Contact, And Transcultural Assimilation in Chrétien de Troyes’s Cligés Levilson C. Reis Otterbein University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/mlanguages_fac Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Repository Citation Reis, Levilson C., "The »Other« Medieval French Alexander: Arthurian Orientalism, Cross-Cultural Contact, And Transcultural Assimilation in Chrétien de Troyes’s Cligés" (2013). Modern Languages & Cultures Faculty Scholarship. 14. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/mlanguages_fac/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages & Cultures at Digital Commons @ Otterbein. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages & Cultures Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Otterbein. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Romanische Forschungen , 125 (3), 2013 The “Other” Medieval Alexander The »Other« Medieval French Alexander: Arthurian Orientalism, Cross- Cultural Contact, And Transcultural Assimilation in Chrétien de Troyes’s Cligés Résumé/Abstract En tenant compte du climat xénophobe des croisades cet article recense la réception de Cligés , roman de Chrétien de Troyes dont la plus grande partie de l’action se passe en Grèce, et explore les stratégies dont l’auteur se serait servi pour en déjouer un mauvais accueil. On examine d’abord les idées que les Francs se faisaient des Grecs par le biais de la réception contemporaine de l’ Énéide et du Roman d’Alexandre . On examine par la suite comment Cligés cadre avec ces perspectives. -

Rathmichael Historical Record 1978-9

Rathmichael Historical Record The Journal of the Rathmichael Historical Society 1 Rathmichael Record Editor M. K. Turner 1978 1979 Contents Page Editorial 3 Winter talks 1978 4 Summer visits Carrigdolgen 7 Tallaght 7 Delgany area 8 Old Rathmichael 9 Baltinglas 9 Kingstown - A portrait of an Irish Victorian town 11 Winter talks 1979 17 Summer outings 1979 Trim 20 Piperstown Hill 20 Rathgall 20 A glass of Claret 22 Course in Field Archaeology 26 2 Editorial Owing to pressure of work it is becoming increasingly difficult to produce the Record in time. We are, therefore, combining the two years 1978 and 1979 in this issue, Octocentenary Eight hundred years ago two documents of the greatest importance to students of the ‘churchscape’ in the dioceses of Dublin and Glendalough, issued from the Lateran Palace in Rome. I refer to the Papal Bulls of April 20th and May 13th 1179, in which Pope Alexander III, at the request of Laurence, Archbishop of Dublin and Malchus, Bishop of Glendalough, confirmed to them their rights over the churches in their respective dioceses. These documents occur among the great number of ‘records of Church interest collected and annotated by Alen, Archbishop of Dublin, 1529-34. Collated and edited, these records are known to students of the medieval Church as “Archbishop Alen’s Register”. In the introduction to his edition, Dr. Charles McNeill calls it “one of the precious pre-Reformation records of the See of Dublin... records transcribed into it...from originals still extant in Archbishop Alen’s time...beginning in 1155 and continuing down to 1533”. -

The Latin Principality of Antioch and Its Relationship with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1188-1268 Samuel James Wilson

The Latin Principality of Antioch and Its Relationship with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1188-1268 Samuel James Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 1 Copyright Statement This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed to the owner of the Intellectual Property Rights. 2 Abstract The Latin principality of Antioch was founded during the First Crusade (1095-1099), and survived for 170 years until its destruction by the Mamluks in 1268. This thesis offers the first full assessment of the thirteenth century principality of Antioch since the publication of Claude Cahen’s La Syrie du nord à l’époque des croisades et la principauté franque d’Antioche in 1940. It examines the Latin principality from its devastation by Saladin in 1188 until the fall of Antioch eighty years later, with a particular focus on its relationship with the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia. This thesis shows how the fate of the two states was closely intertwined for much of this period. The failure of the principality to recover from the major territorial losses it suffered in 1188 can be partly explained by the threat posed by the Cilician Armenians in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. -

Cry Havoc Règles Fr 20/07/17 10:50 Page1

ager historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 20/07/17 10:50 Page1 HISTORY & SCENARIOS ager historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 20/07/17 10:50 Page2 © Buxeria & Historic’One éditions - 2017 - v1.0 ager historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 20/07/17 10:50 Page3 SELJUK SULTANATE OF RUM Konya COUNTY OF EDESSA Sis PRINCIPALITY OF ARMENIAN CILICIA Edessa Tarsus Turbessel Harran BYZANTINE EMPIRE Antioch Aleppo PRINCIPALITY OF ANTIOCH Emirate of Shaïzar Isma'ili COUNTY OF GRAND SELJUK TRIPOLI EMPIRE Damascus Acre DAMASCUS F THE MIDDLE EAST KINGDOM IN 1135 TE O OF between the First JERUSALEM and Second Crusades Jerusalem EMIRA N EW S FATIMID 0 150 km CALIPHATE ager historique UK_cry havoc règles fr 20/07/17 10:43 Page1 History The Normans in Northern Syria in the 12th Century 1. Historical background Three Normans distinguished themselVes during the First Crusade: Robert Curthose, Duke of NormandY and eldest son of William the Conqueror 1 Whose actions Were decisiVe at the battle of DorYlea in 1197, Bohemond of Taranto, the eldest son of Robert Guiscard 2, and his nepheW Tancred, Who led one of the assaults upon the Walls of Jerusalem in 1099. Before participating in the crusade, Bohemond had been passed oVer bY his Younger half-brother Roger Borsa as Duke of Puglia and Calabria on the death of his father in 1085. Far from being motiVated bY religious sentiment like GodfreY of Bouillon, the crusade Was for him just another occasion to Wage War against his perennial enemY, BYZantium, and to carVe out his oWn state in the HolY Land. -

The Second Crusade, 1145-49: Damascus, Lisbon and the Wendish Campaigns

The Second Crusade, 1145-49: Damascus, Lisbon and the Wendish Campaigns Abstract: The Second Crusade (1145-49) is thought to have encompassed near simultaneous Christian attacks on Muslim towns and cities in Syria and Iberia and pagan Wend strongholds around the southern shore of the Baltic Sea. The motivations underpinning the attacks on Damascus, Lisbon and – taken collectively – the Wendish strongholds have come in for particular attention. The doomed decision to assault Damascus in 1148 rather than recover Edessa, the capital of the first so-called crusader state, was once thought to be ill-conceived. Historians now believe the city was attacked because Damascus posed a significant threat to the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem when the Second Crusaders arrived in the East. The assault on Lisbon and the Wendish strongholds fell into a long-established pattern of regional, worldly aggression and expansion; therefore, historians tend not to ascribe any spiritual impulses behind the native Christians’ decisions to attack their enemies. Indeed, the siege of Lisbon by an allied force of international crusaders and those of the Portuguese ruler, Afonso Henriques, is perceived primarily as a politico-strategic episode in the on-going Christian-Muslim conflict in Iberia – commonly referred to as the reconquista. The native warrior and commercial elite undoubtedly had various temporal reasons for engaging in warfare in Iberia and the Baltic region between 1147 and 1149, although the article concludes with some notes of caution before clinically construing motivation from behaviour in such instances. On Christmas Eve 1144, Zangī, the Muslim ruler of Aleppo and Mosul, seized the Christian-held city of Edessa in Mesopotamia. -

The Byzantine Emperor John II's Syrian Expeditions And

論 文 オ リエ ン ト 49-2(2006):70-90 ヨ ハ ン ネ ス2世 の シ リ ア 遠 征 と ザ ン ギ ー の 南 進 策 ―12世紀 前半 シ リアの勢力構図の変動― The Byzantine Emperor John II's Syrian Expeditions and Zangi's Strategy for Southern Syria: The Change in the Balance of Power which Syria Experienced in the First Half of the Twelfth Century 中 村 妙 子 NAKAMURA Taeko ABSTRACT The Byzantine emperor John II made Syrian expeditions twice, in the 1130s and 1140s. From the beginning of the twelfth century, the Syrian cities and the Crusader States preserved the balance of power through economic agreements and military alliances. However, Zangi, ruler of Aleppo, refused to maintain this balance-of-power policy and started to advance southward in Syria to recover lost territories from the Crusaders and obtain farmland which was under Damascus' rule. John carried out his expedition at this time. John compelled Raymond of Poitiers, the consort of the heiress of Antioch, to become his liege vassal. John and Raymond agreed that Raymond would hand Antioch over to John in return for cities, currently in Muslim hands, which John would capture leading a joint Byzantine-Cru- sader army. But Raymond had John attack cities whose power Raymond himself wanted to reduce. Also, as the nobility of Antioch, who had come from south Italy, had influence over Raymond, John could not appoint a Greek Orthodox cleric as patriarch of Antioch. Furthermore, an encyclical issued by Pope Innocent II stating that all Latins serving in the Byzantine army were forbidden to attack Christians in Crusader States, forced John to reduce his claims on Antioch, being conscious of the West's eyes. -

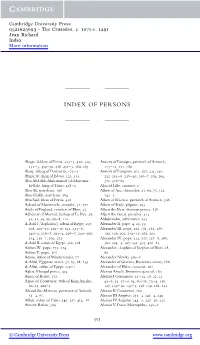

Index of Persons

Cambridge University Press 0521623693 - The Crusades, c. 1071-c. 1291 Jean Richard Index More information ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ INDEX OF PERSONS ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ Abaga, il-khan of Persia, 423±4, 426, 429, Aimery of Limoges, patriarch of Antioch, 432±3, 439±40, 446, 452±3, 460, 463 113±14, 171, 180 Abaq, atabeg of Damascus, 173±4 Aimery of Lusignan, 201, 207, 225, 230, Abgar, St, king of Edessa, 122, 155 232, 235±6, 238±40, 256±7, 264, 294, Abu Abdallah Muhammad (al-Mustansir 371, 376±80 bi-llah), king of Tunis, 428±9 Alan of Lille, canonist, 2 Abu Ali, merchant, 106 Albert of Aix, chronicler, 21, 69, 75, 123, Abu Ghalib, merchant, 384 142±3 Abu Said, khan of Persia, 456 Albert of Rizzato, patriarch of Antioch, 396 Achard of Montmerle, crusader, 31, 271 Albert of Stade, pilgrim, 293 Adela of England, countess of Blois, 35 Albert the Bear, German prince, 158 AdheÂmar of Monteil, bishop of Le Puy, 28, Albert the Great, preacher, 413 32, 42, 49, 60, 66±8, 112 Aldobrandin, adventurer, 254 al-Adil I (`Saphadin'), sultan of Egypt, 197, Alexander II, pope, 4, 23, 39 208, 209±10, 229±30, 232, 235±6, Alexander III, pope, 122, 181, 185, 188, 240±2, 256±7, 293±4, 296±7, 299±300, 190, 199, 202, 214±15, 260, 292 314, 350±1, 362, 375 Alexander IV, pope, 335, 337, 357±8, 360, al-Adil II, sultan of Egypt, 322, 328 362, 364±5, 367, 391, 397, 410±13 Adrian IV, pope, 175, 214 Alexander, chaplain of Stephen of Blois, 28, Adrian V, pope, 385 60 Adson, abbot of MontieÂrender, 17 Alexander Nevski, 360±1 al-Afdal, Egyptian vizier, 57, 65, 68, 139 Alexander of Gravina, -

Who Was Who in Medieval Limerick; from Manuscript Sources

Who Was Who in Medieval Limerick; from Manuscript Sources. (updated 22/01/2012) by Brian Hodkinson, Assistant Curator, Limerick Museum ©. (Changes since first uploaded to be found as an appendix) The following list is compiled for my own personal research into medieval Limerick and is offered in the knowledge that it is not perfect. I hope it can be used as a tool to kick start research into various aspects of medieval Limerick. The list is compiled mostly from indexes to calendared documents, looking up all references under “Limerick” or in the case of CJR the locations at the side of the text. Lenihan’s mayoral list has been avoided because it was compiled at a later date and cannot, for the medieval period, be shown to be authentic. In many cases, such as the papal documents, it is highly probable that there are extra references to individuals who started or ended their career outside Limerick. Some people are known to have played a part on the wider national stage, but only Limerick references are listed here. Bishops are listed in chronological order under Limerick. Where I have anglicised names, I have often put the original spelling in brackets afterwards, variant spellings are treated likewise, so it is worth using “find on page” facility. All “sons of” are listed under Fitz. Given the vagaries of medieval spelling it is highly likely that the same person may be entered twice. The list is there to be improved so if you spot errors, have reasonable grounds to combine entries or have extra references then please let me know at [email protected] If you pursue the career of someone in the list outside Limerick, then references in the same format can be added. -

Private Sources at the National Archives

Private Sources at the National Archives Small Private Accessions 1972–1997 999/1–999/850 1 The attached finding-aid lists all those small collections received from private and institutional donors between the years 1972 and 1997. The accessioned records are of a miscellaneous nature covering testamentary collections, National School records, estate collections, private correspondence and much more. The accessioned records may range from one single item to a collection of many tens of documents. All are worthy of interest. The prefix 999 ceased to be used in 1997 and all accessions – whether large or small – are now given the relevant annual prefix. It is hoped that all users of this finding-aid will find something of interest in it. Paper print-outs of this finding-aid are to be found on the public shelves in the Niall McCarthy Reading Room of the National Archives. The records themselves are easily accessible. 2 999/1 DONATED 30 Nov. 1972 Dec. 1775 An alphabetical book or list of electors in the Queen’s County. 3 999/2 COPIED FROM A TEMPORARY DEPOSIT 6 Dec. 1972 19 century Three deeds Affecting the foundation of the Loreto Order of Nuns in Ireland. 4 999/3 DONATED 10 May 1973 Photocopies made in the Archivio del Ministerio de Estado, Spain Documents relating to the Wall family in Spain Particularly Santiago Wall, Conde de Armildez de Toledo died c. 1860 Son of General Santiago Wall, died 1835 Son of Edward Wall, died 1795 who left Carlow, 1793 5 999/4 DONATED 18 Jan. 1973 Vaughan Wills Photocopies of P.R.O.I. -

Introduction the Second Crusade: Main Debates and New Horizons

Introduction The Second Crusade: Main Debates and New Horizons Jason T. Roche The modern era of Second Crusade studies began with a seminal article by Giles Constable entitled ‘The Second Crusade as seen by Contemporaries’ (1953). Constable focuses on the central role of Pope Eugenius III and his fellow Cistercian, Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux, in the genesis and expansion in scope of the Second Crusade. He pays particular attention to what has become known as the Syrian campaign. But his central thesis maintains that by the spring of 1147 and the issuing of the papal bull Divina dispensatione (II), Pope Eugenius III ‘viewed and planned’ the venture as a general Christian offensive against a number of the Church’s enemies. Thus, the siege of the Syrian Muslim city of Damascus in 1148 and the expeditions of the same year directed against the Baltic strongholds of Dobin, Demmin and Szczecin situated in the pagan Slav lands east of the River Elbe formed part of what we now call the Second Crusade. The supposed scope of the venture was even greater than this: the Christian attacks on the Muslim-held Iberian cities and strongholds of Santarém, Lisbon, Cinta, Almada and Palmela in 1147, Faro, Almería and Tortosa in 1148, and Lérida and Fraga in 1149 also formed part of the same single enterprise to secure and expand the peripheries of Latin Christendom.1 Constable’s work has proved very influential over the past two decades. The volume of articles entitled The Second Crusade and the Cistercians (1992), edited by Michael Gervers, addresses the impact of Cistercian monks on the crusade movement. -

Appendix: Masters of the Hospital

Appendix: Masters of the Hospital Note: square brackets are used of those who were temporarily in charge (like Lt. Masters) or are doubtful. Gerard (1099–1120) [Roger, Lieutenant Master?] Raymond of Puy (1120–1158×1160) Auger of Balben (1158×1160–1162)1 [Arnold of Comps? (1162–1163)] Gilbert of Assailly (1163–1171) Cast of Murols (1171–72) [Rostang Anti-master? (1171)] Jobert (1172–1177) Roger of Moulins (1177–1187)2 [Ermengol of Aspa, Provisor (1188–1190)] Garnier of Nablus (1190–1192) Geoffrey of Donjon (1193–1202)3 Alfonso of Portugal (1203–1206) Geoffrey Le Rat (1206–1207) Garin of Montaigu (1207–1227×1228) Bertrand of Thessy or Le Lorgne (1228–1230×1231) Guérin (1230×1231–1236)4 Bertrand of Comps (1236–1239×1240)5 Peter of Vieille Bride (1240–1241) William of Châteauneuf (1241–1258) [ John of Ronay, Lieutenant Master (1244–50)] Hugh Revel (1258–1277×1278) Nicholas Lorgne (1277×1278–1285) John of Villiers (1285–1293×1294) Odo of Pins (1293×1294–1296) William of Villaret (1296–1305) Fulk of Villaret (1305–1317×1319) 233 Notes Explication and Acknowledgements 1. Joseph Delaville Le Roulx, Les Hospitaliers en Terre Sainte et à Chypre (1100–1310) (Paris, 1904); Hans Prutz, Die geistlichen Ritterorden (Berlin, 1908). 2. Jonathan Riley-Smith, The Knights of St John in Jerusalem and Cyprus, c.1050–1310 (London, 1967). 3. Rudolf Hiestand, ‘Die Anfänge der Johanniter’, in Die geistlichen Ritterorden Europas, ed. Josef Fleckenstein and Manfred Hellmann (Sigmaringen, 1980); Alain Beltjens, Aux origi- nes de l’Ordre de Malte (Brussels, 1995); Anthony Luttrell, ‘The Earliest Hospitallers’, in Montjoie, ed. -

CONCLUSION Ores Leissons Ia Vanite, Et Tenons Ia Verite WILLIAM of S

CONCLUSION Ores leissons Ia vanite, et tenons Ia verite WILLIAM OF S. STEFANO Long before the disastrous Battle of Battin the Latin Kingdom ... was beginning to lean more and more upon the military religious orders ... Continually reinforced from Europe by a regular flow of recruits of the very best military type, their efficiency was unimpaired by the adverse Oriental environment, and they remained the only really stable and wholesome elements in the state ... there can be no two opinions as to the entirely devoted and self-sacrificing manner in which they carried out their arduous duties. 1 The great Orders of chivalry, Templars, Hospitallers, Teutonic Knights, became as much states within a state, having their own policy ... often dictated by their financial interests and opposed to the most evident needs of the country .... They did not care about this derisory state except in so far as they could occasionally make it serve their ends, involving it in their personal wars for their particular interests. 2 These irreconcilable views of the Military Orders are extreme expressions of two schools of history. To the first have belonged nearly all the historians of the Military Orders, the majority of whom, it should be remembered, were themselves connected with descendant branches of the Order of St. John. To the second has subscribed nearly every historian of the Crusades and the crusader states. The supporters of the first argue that the members of the Military Orders were robust exponents of a worthwhile ideal. While admitting that they were often selfish and disorderly, they believe that their qualities far outweighed their defects.