Rathmichael Historical Record 1978-9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rathmichael Historical Record 1998 Editor: Rosemary Beckett Assisted by Rob Goodbody Published by Rathmichael Historical Society, July 2000

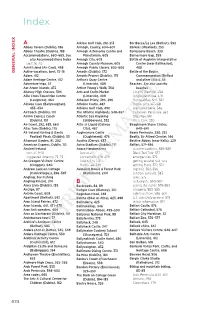

1 The Journal of the Rathmichael Historical Society Rathmichael Historical Record 1998 Editor: Rosemary Beckett Assisted by Rob Goodbody Published by Rathmichael Historical Society, July 2000. Contents Secretary‟s Report, 1998 1 22nd. AGM and member‟s slides 2 Deane & Woodward -F O‟Dwyer 4 Hidden in the Pile - M Johnston 8 Dublin -1 Lumley 10 Outing to Co Offaly 12 Outing to Larchill Co Kildare 13 Outing to Wicklow Gaol & Avondale. 14 24th Summer School Evening Lectures 16 Outing to St Mary‟s Abbey 24 Suburban townships of Dublin - S Ó Maitiú 25 The excavation at Cabinteely - M Conway 27 A Shooting at Foxrock - J Scannell 28 Byways of research - J Burry 33 A “find” in Rathmichael - R Goodbody 34 Questionnaire to Members 35 Report on Questionnaire 38 Secretary’s Report, 1998 This year was another busy year for the Society‟s members and committee. There were five monthly lectures, an evening course, four outings and ten committee meetings. The Winter season resumed, following the AGM with a lecture in February by Frederick O‟Dwyer on The Architecture of Deane and Woodward. This was followed in March by Mairéad Johnson who spoke on the Abbeyleix carpet factory and concluded in April with an illustrated lecture by Ian Lumley on “Changing Dublin”. The Summer season began in May with members of the Society joining a guided tour of some of the lesser known monastic sites of County Offaly. In June we visited Larchill in County Kildare, Wicklow gaol and court-house and Avondale House in July, and St Mary‟s Abbey and Marsh‟s Library on Heritage Sunday in September. -

Martello Towers Research Project

Martello Towers Research Project March 2008 Jason Bolton MA MIAI IHBC www.boltonconsultancy.com Conservation Consultant [email protected] Executive Summary “Billy Pitt had them built, Buck Mulligan said, when the French were on the sea”, Ulysses, James Joyce. The „Martello Towers Research Project‟ was commissioned by Fingal County Council and Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council, with the support of The Heritage Council, in order to collate all known documentation relating to the Martello Towers of the Dublin area, including those in Bray, Co. Wicklow. The project was also supported by Dublin City Council and Wicklow County Council. Martello Towers are one of the most well-known fortifications in the world, with examples found throughout Ireland, the United Kingdom and along the trade routes to Africa, India and the Americas. The towers are typically squat, cylindrical, two-storey masonry towers positioned to defend a strategic section of coastline from an invading force, with a landward entrance at first-floor level defended by a machicolation, and mounting one or more cannons to the rooftop gun platform. The Dublin series of towers, built 1804-1805, is the only group constructed to defend a capital city, and is the most complete group of towers still existing in the world. The report begins with contemporary accounts of the construction and significance of the original tower at Mortella Point in Corsica from 1563-5, to the famous attack on that tower in 1794, where a single engagement involving key officers in the British military became the catalyst for a global military architectural phenomenon. However, the design of the Dublin towers is not actually based on the Mortella Point tower. -

From the Service of the Sea to the Service Of

FREE April 2018 22 From the Service of the Sea to the Service of God During the period when Fr. Nevin and Fr. Carroll were working Having received them, the committee contacted Alec Wolohan at Kilmacanogue Church together with Parish Priest Fr. Farnan, a who has a saw mill in Raheen, outside Roundwood. Alec had the large amount of maintenance and improvements were carried out timber x-rayed for foreign particles that could damage the saw, he on the church. Among these improvements were the replacement then cut them in 32mm thick planks. The timber turned out very of the main Altar, Reading Dias and Baptismal Font and the story well with no cracks and a beautiful pitch pine cent. All the planks behind their creation is worth recording. When the church authority were then given to Garry King at his workshop in Calary, where recommended that the Priest should face the congregation during he planed and shaped them to the drawings provided. Garry services some years ago. The original Altar front was moved out. provided samples of what could be created and went ahead to However, it was always found that the Altar table was too narrow give us a First-Class Alter. The Altar was fitted into the church in and restrictive to work on. Following a lot of discussion, and soul April 2000 and enough timber was available to provide a Reading searching, it was decided to replace the Altar with a new and more Dias and a base for our Baptismal Font. serviceable one. The black limestone Font was the originally used Font in the church The maintenance committee at the time together with the Priest but had been left unused for many years before being repaired investigated the best way to provide an Altar in keeping with the and fitted to the base. -

Listing and Index of Evening Herald Articles 1938 ~ 1975 by J

Listing and Index of Evening Herald Articles 1938 ~ 1975 by J. B. Malone on Walks ~ Cycles ~ Drives compiled by Frank Tracy SOUTH DUBLIN LIBRARIES - OCTOBER 2014 SOUTH DUBLIN LIBRARIES - OCTOBER 2014 Listing and Index of Evening Herald Articles 1938 ~ 1975 by J. B. Malone on Walks ~ Cycles ~ Drives compiled by Frank Tracy SOUTH DUBLIN LIBRARIES - OCTOBER 2014 Copyright 2014 Local Studies Section South Dublin Libraries ISBN 978-0-9575115-5-2 Design and Layout by Sinéad Rafferty Printed in Ireland by GRAPHPRINT LTD Unit A9 Calmount Business Park Dublin 12 Published October 2014 by: Local Studies Section South Dublin Libraries Headquarters Local Studies Section South Dublin Libraries Headquarters County Library Unit 1 County Hall Square Industrial Complex Town Centre Town Centre Tallaght Tallaght Dublin 24 Dublin 24 Phone 353 (0)1 462 0073 Phone 353 (0)1 459 7834 Email: [email protected] Fax 353 (0)1 459 7872 www.southdublin.ie www.southdublinlibraries.ie Contents Page Foreword from Mayor Fintan Warfield ..............................................................................5 Introduction .......................................................................................................................7 Listing of Evening Herald Articles 1938 – 1975 .......................................................9-133 Index - Mountains ..................................................................................................134-137 Index - Some Popular Locations .................................................................................. -

Definitive Guide to the Top 500 Schools in Ireland

DEFINITIVE GUIDE TO THE TOP 500 SCHOOLS IN IRELAND These are the top 500 secondary schools ranked by the average proportion of pupils gaining places in autumn 2017, 2018 and 2019 at one of the 10 universities on the island of Ireland, main teacher training colleges, Royal College of Surgeons or National College of Art and Design. Where schools are tied, the proportion of students gaining places at all non-private, third-level colleges is taken into account. See how this % at university Boys Girls Student/ staff ratio Telephone % at third-level Area Type % at university Boys Girls Student/ staff ratio Telephone Rank Previous rank % at third-level Type % at university Boys Girls Student/ staff ratio Telephone Area Type Rank Previous rank Area % at third-level guide was compiled, back page. Schools offering only senior cycle, such as the Institute of Education, Dublin, and any new schools are Rank Previous rank excluded. Compiled by William Burton and Colm Murphy. Edited by Ian Coxon 129 112 Meanscoil Iognaid Ris, Naas, Co Kildare L B 59.9 88.2 1,019 - 14.1 045-866402 269 317 Rockbrook Park School, Rathfarnham, Dublin 16 SD B 47.3 73.5 169 - 13.4 01-4933204 409 475 Gairmscoil Mhuire, Athenry, Co Galway C M 37.1 54.4 266 229 10.0 091-844159 Fee-paying schools are in bold. Gaelcholaisti are in italics. (G)=Irish-medium Gaeltacht schools. *English-speaking schools with Gaelcholaisti 130 214 St Finian’s College, Mullingar, Co Westmeath L M 59.8 82.0 390 385 13.9 044-48672 270 359 St Joseph’s Secondary School, Rush, Co Dublin ND M 47.3 63.3 416 297 12.3 01-8437534 410 432 St Mogue’s College, Belturbet, Co Cavan U M 37.0 59.0 123 104 10.6 049-9523112 streams or units. -

Dear Parishioners and Friends, God Bless Frederick

MARCHMARCH 2019 2019 RATHMICHAEL PARISH NEWSLETTER www.rathmichael.dublin.anglican.org Dear Parishioners and friends, These are some of the less savoury bits and pieces of parish, school and wider life for each to Gosh. My last rector’s letter after 26½ years. Do I say look out for and challenge head on for everyone’s all nice things about parish ministry or do I tell the sake. truth? Whichever, I wager that few enough parishes are When I was appointed to Rathmichael Archbishop blessed with such competent people who voluntarily Donald Caird summoned me to “Marry the High take on the many tasks of administration, prayer Road and the Low Road and work assiduously on support and otherwise in a parish to keep life and soul the school.” There was only one response to that in the community. archbishop. “Yes boss”. And see how that turned out:- Being a parish rector is a peculiar old business. There is the dichotomy of needing to be as hard as nails in some situations and with some people, against hope- fully the default position of being pastoral from deep within one’s heart in other situations. Over time roots grow into one’s heart and when death or other reason rips them out it can be difficult to smile sincerely for awhile. The ‘loading’ of Small issues versus Big issues can be a frustration in ministry and school management. Where great good is being affected, there a countering evil force in the spiritual realm will be present. The opening lines of the Evening Service of Compline (page 154) are clear if a tad blunt. -

Killiney Hill Trail

Killiney Hill Trail • This trail will take approximately two hours. • It could be divided into two halves (Stopes 1-3 and Stops 4-7). • It is designed for senior classes. • One booklet per group, with extra paper for activities. • One adult is required with each group of 4-6. • We recommend that the teacher should complete the trail in advance . Pencil and eraser A4 white paper Compass 1. Make sure you have Measuring tape everything you need. String One camera per group. 2. Write your name and the date on your sheet. 3. Remember the rules. Stay with your group. 4. Remember to use all your senses at every station and to have fun! 1 Killiney Hill Trail Do not go down steep steps. Continue up to tower. To get to Stop 4 follow signs 3 for tea rooms. 1 Look out for a little lane on 7 2 your left! Go up that. Toilets/ 4 Off the beaten coffee shop track into the 6 forest. 5 Created July 2017 by: Paula Murphy, Tania Daly, Paul Twomey, Ann-Marie Kenrick, Ann-Marie Greene and Ciara McCarrick The Memory Stone Stop 1 Killiney Hill mark is a combination of Dalkey Hill, Killiney Hill and Roches Image Hill. It was opened to the public as related Victoria Hill in 1887, and re-named to info as Killiney Hill in 1920. Enjoy lgkndfl;fthe woodlands, the magnificent 1830 2017 Enjoy the woodlands, the magnificent seascapes and learn some fascinating local history. Your task, as you move from stop to stop, is to locate the Follow the path monuments, statues and in a south-east objects photographed on direction to Stop page 2, and tick them off. -

June 2011) June: in Honour of the Goddess Juno, Patroness of Women, Marriage and the Home

DALKEY - Deilginis ‘Thorn Island’ COMMUNITY COUNCIL Irish Heritage Town First Published April 1974 NEWSLETTER No 409 (Volume 17) Meitheamh (June 2011) June: In honour of the Goddess Juno, patroness of women, marriage and the home. A swarm of bees in May is worth a load of hay. A swarm of bees in June is worth a silver spoon. A swarm of bees in July is not worth a fly. Guímid Lá Shona, shuaireach do gach Athair in Deilginis! We wish a happy enjoyable Father’s Day to all the Dads in Dalkey Flower: on June 19th! Rose Sorrento Terrace and Dalkey Island viewed from The Vico Bathing Place. Photograph by Dalkey resident John Fahy. See www.dalkeyphotos.com for more Your Area Representative is............................................................................................. Telephone:........................................... E-Mail:.................................................... ❖ SUMMARY OF DCC MAY MONTHLY MEETING ❖ The DCC May Meeting was held in the Harold Boys School on Tuesday 3rd May. Treasurer: The annual subscription envelopes are being returned and Ed encouraged the Road Reps to collect outstanding envelopes as soon as possible. DTT: The summer Litter Patrols will be commencing from the 1st June and new volunteers are most welcome. The litter bin at the entry/exit to the DART station has been removed and this matter will be investigated. NW: Gardai have informed us to be vigilant and as the summer approaches parents should be aware of the whereabouts of their children. Gardai have said that they will disperse gangs of young people drinking and take the alcohol from them. As there was no further business the meeting ended. ❖ DALKEY CASTLE & HERITAGE CENTRE ❖ There is an exciting time ahead in Dalkey for those interested in books, reading, literary pursuits and general festival atmosphere! Firstly we will have the Bloomsday Festival on Thursday 16th June, followed by the Dalkey Book Festival from 17-19th. -

Rathmichael Historical Record 2001 Published by Rathmichael Historical Society 2003 SECRETARY's REPORT—2001

CONTENTS Secretary's Report ........................................ • .... 1 25th-A GM.: ........................................................ 2 Shipwrecks in and around Dublin Bay..................... 5 The Rathdown Union Workhouse 1838-1923 .......... 10 Excavations of Rural Norse Settlements at Cherrywood ........................................................ 15 Outing to Dunsany Castle ...................................... 18 Outing to some Pre-historic Tombs ......................... 20 27th Summer School. Evening lectures .................. 21 Outing to Farmleigh House .................................... 36 Weekend visit to Athenry ....................................... 38 Diarmait MacMurchada ......................................... 40 People Places and Parchment ................................... 47 A New Look at Malton's Dublin, ............................. 50 D. Leo Swan An Appreciation ................................. 52 Rathmichael Historical Record 2001 Published by Rathmichael Historical Society 2003 SECRETARY'S REPORT—2001. Presented January 2002 2001 was another busy year for the society's members and committee. There were six monthly lectures, and evening course, four field trips, an autumn weekend away and nine committee meetings. The winter season resumed, following the AGM with a lecture in February by Cormac Louth on Shipwrecks around Dublin Bay. In March Eva 6 Cathaoir spoke to us on The Rathdown Union workhouse at Loughlinstown in the period 1838-1923 and concluded in April with John 6 Neill updating -

Rathmichael Historical Record 1980-1

1 Rathmichael Record Editor: M. K. Turner 1980 1981 2 Winter Talks – 1980 Friday, January 18th - The Annual General Meeting was held on January 18th when the following officers and committee were elected:- President - Mr Gerard Slevin Committee: - Hon. Secretary - Mrs Joan Delany Mrs M. K. Turner Hon. Treasurer - Mr James McNamara Miss Mary Treston Col D. Boydell Mr. P.J. Corr Mr. R.C. Pilkington, as the longest-standing member of the Committee, retired temporarily. Following on the business of the meeting, an illustrated talk entitled Excavations at Kilteel was given by Mr. Conleth Manning. This talk was particularly interesting to students of the Archaeology Course who had themselves done some work on this site. There was a good attendance. Friday, February 15th - Our President, Mr. Gerard Slevin, Chief Herald of Ireland, gave a very interesting talk on History in Bookplates with many fascinating illustrations. Friday, October 17th - An illustrated talk entitled “Irish Ceramics” was given by Mrs. Maireád Reynolds of the National Museum. Friday, November 21st For the second time Mrs. Betty O’Brien, one of our members, gave us an illustrated talk. The subject tonight -Some pre-Norman Churches in South County Dublin , was especially interesting to those of us who are already familiar with some of the churches mentioned. We know that these have recently been studied in considerable detail by the speaker. We would like to take this opportunity to offer our congratulations to Betty O’Brien on gaining her M.A. (UCD) degree in Archaeology a few months ago. We look forward to further talks from her. -

Lands at Dalkey Manor

For Sale by Private Treaty LANDS AT DALKEY MANOR BARNHILL ROAD, DALKEY, COUNTY DUBLIN LANDS AT DALKEY MANOR BARNHILL ROAD, DALKEY, COUNTY DUBLIN 0.937HA (2.32 ACRES) APPROX. Excellent Residential Development Opportunity with FPP for 13 houses and 23 apartments Located off Barnhill Road in Dalkey and is approximately 400 metres west of Dalkey Village centre of various local amenities Residential Development opportunity extending to approx. 0.937ha (2.32 acres) Excellent accessibility - DART (750m), Dublin Bus (Barnhill Road), Aircoach (400m) Indicative Site Outline 2 3 Dun Laoghaire Pier DÚN LAOGHAIRE Dublin Bay Adelaide Road 40 Foot LOCATION This exceptional residential site is located off Barnhill Road in Dalkey. The picturesque village of Dalkey, with its medieval streetscape is nestled on the southern end of Dublin Bay. It is located approximately 13 km (half an hour drive) from DART DALKEY Dublin City Centre and is on the Dalkey DART line. The subject site is located approximately 750m from Dalkey DART Station, which is located on Railway Road. It is ideally situated with approx. 24 meters of frontage onto the exclusive Barnhill Road. Additionally, the property is within approx. 400 Hyde Park metres of the busy Castle Street in Dalkey Village. Accessibility is key and the N11 is within approx. Barnhill Road 4km providing easy access to the city centre and the M50. Dalkey is a popular residential location for both the Irish and International elite. The area is largely unspoiled, has an old world charm and is set among spectacular scenery with an awe inspiring coast line which encompasses beautiful beaches and cliffs, the attractive Colliemore Harbour and unspoilt Dalkey Island. -

Copyrighted Material

Index A Arklow Golf Club, 212–213 Bar Bacca/La Lea (Belfast), 592 Abbey Tavern (Dublin), 186 Armagh, County, 604–607 Barkers (Wexford), 253 Abbey Theatre (Dublin), 188 Armagh Astronomy Centre and Barleycove Beach, 330 Accommodations, 660–665. See Planetarium, 605 Barnesmore Gap, 559 also Accommodations Index Armagh City, 605 Battle of Aughrim Interpretative best, 16–20 Armagh County Museum, 605 Centre (near Ballinasloe), Achill Island (An Caol), 498 Armagh Public Library, 605–606 488 GENERAL INDEX Active vacations, best, 15–16 Arnotts (Dublin), 172 Battle of the Boyne Adare, 412 Arnotts Project (Dublin), 175 Commemoration (Belfast Adare Heritage Centre, 412 Arthur's Quay Centre and other cities), 54 Adventure trips, 57 (Limerick), 409 Beaches. See also specifi c Aer Arann Islands, 472 Arthur Young's Walk, 364 beaches Ahenny High Crosses, 394 Arts and Crafts Market County Wexford, 254 Aille Cross Equestrian Centre (Limerick), 409 Dingle Peninsula, 379 (Loughrea), 464 Athassel Priory, 394, 396 Donegal Bay, 542, 552 Aillwee Cave (Ballyvaughan), Athlone Castle, 487 Dublin area, 167–168 433–434 Athlone Golf Club, 490 Glencolumbkille, 546 AirCoach (Dublin), 101 The Atlantic Highlands, 548–557 Inishowen Peninsula, 560 Airlink Express Coach Atlantic Sea Kayaking Sligo Bay, 519 (Dublin), 101 (Skibbereen), 332 West Cork, 330 Air travel, 292, 655, 660 Attic @ Liquid (Galway Beaghmore Stone Circles, Alias Tom (Dublin), 175 City), 467 640–641 All-Ireland Hurling & Gaelic Aughnanure Castle Beara Peninsula, 330, 332 Football Finals (Dublin), 55 (Oughterard),