The Hopes and the Realities of Aviation in French Indochina, 1919-1940

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cruising Speed: 90 Km/Hr.)

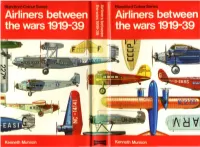

_-........- •- '! • The years between 191 9 and 1939 saw the binh, growth and establishment of the aeroplane as an accepted means of public travel. Beginning in the early post-u•ar years with ajrcraft such as the O.H.4A and the bloated Vimy Commercial, crudely converted from wartime bombers, the airline business T he Pocket Encyclopaed ia of World Aircraft in Colour g radually imposed its ou·n require AIRLINERS ments upon aircraft design to pro duce, within the next nvo decades, between the Wars all-metal monoplanes as handso me as the Electra and the de Havilland Albatross. The 70 aircraft described and illu strated in this volume include rhe trailblazers of today's air routes- such types as the Hercules, H. P.41, Fokker Trimotor, Condor, Henry Fo rd's " Tin Goose" and the immortal DC-3. Herc, too, arc such truly pioneering types as the Junkers F 13 and Boeing l\'fonomajl, and many others of all nationalities, in a wide spectrum of shape and size that ranges fro m Lockheed's tiny 6-scat Vega to the g rotesque Junkers G 38, whose wing leading-edges alone could scat six passengers. • -"l."':Z'.~-. .. , •• The Pocket Encyclopaedia of \Vorld Aircraft in Colour AIRLINERS between the Wars 1919- 1939 by KENNETH M UNS O N Illustrated by JOHN W. WOOD Bob Corrall Frank Friend Brian Hiley \\lilliam Hobson Tony ~1it chcll Jack Pclling LONDON BLANDFORD PRESS PREFACE First published 1972 © 1972 Blandford Press Lld. 167 H igh llolbom, London \\IC1\' 6Pl l The period dealt \vith by this volurne covers both the birth and the gro\vth of air transport, for Lhere "·ere no a irlines ISBN o 7137 0567 1 before \Vorld \\'ar 1 except Lhose operated by Zeppelin air All rights reserved. -

Indochina 1900-1939"

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/35581 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. "French Colonial Discourses: the Case of French Indochina 1900-1939". Nicola J. Cooper Thesis submitted for the Qualification of Ph.D. University of Warwick. French Department. September 1997. Summary This thesis focuses upon French colonial discourses at the height of the French imperial encounter with Indochina: 1900-1939. It examines the way in which imperial France viewed her role in Indochina, and the representations and perceptions of Indochina which were produced and disseminated in a variety of cultural media emanating from the metropole. Framed by political, ideological and historical developments and debates, each chapter develops a socio-cultural account of France's own understanding of her role in Indochina, and her relationship with the colony during this crucial period. The thesis asserts that although consistent, French discourses of Empire do not present a coherent view of the nation's imperial identity or role, and that this lack of coherence is epitomised by the Franco-indochinese relationship. The thesis seeks to demonstrate that French perceptions of Indochina were marked above all by a striking ambivalence, and that the metropole's view of the status of Indochina within the Empire was often contradictory, and at times paradoxical. -

The Coastwatcher

13 JUN-CTWG Op Eval TRANEX TBA-JUL CTWG Encampment 21-23 AUG-CTWG/USAF Evaluation Missions for 15-23 AUG-NER Glider Academy@KSVF America 26-29 AUG-CAP National Conference Semper vigilans! 12 SEP-Cadet Ball-USCGA Semper volans! CADET MEETING REPORT The Coastwatcher 24 February, 2015 Publication of the Thames River Composite Squadron Connecticut Wing Maj Roy Bourque outlined the Squadron Civil Air Patrol Rocketry Program and set deadlines for Cadet submission of plans. 300 Tower Rd., Groton, CT http://ct075.org . The danger of carbon monoxide poisoning was the subject of the safety meeting. C/2dLt Jessica LtCol Stephen Rocketto, Editor Carter discussed the prevention and detection of [email protected] this hazardous gas and opened up the forum to comments and questions from the Cadets. C/CMSgt Virginia Poe, Scribe C/SMSgt Michael Hollingsworth, Printer's Devil C/CMSgt Virginia Poe delivered her Armstrong Lt David Meers & Maj Roy Bourque, Papparazis Lecture on the “The Daily Benefits of the Hap Rocketto, Governor-ASOQB, Feature Editor Aerospace Program.” Vol. IX 9.08 25 February, 2015 Maj Brendan Schultz delivered his Eaker Lecture explaining the value of leadership skills learned in SCHEDULE OF COMING EVENT the Cadet Program and encouraged Cadets to apply their learning to the world outside of CAP. 03 MAR-TRCS Staff Meeting 10 MAR-TRCS Meeting C/SrA Thomas Turner outlined the history of 17 MAR-TRCS Meeting rocket propulsion from Hero's Aeopile to the 21 MAR-CTWG WWII Gold Medal Ceremony landing on the moon. He then explained each of 24 MAR-TRCS Meeting Newton's Three Laws of Dynamics and showed 31 MAR-TRCS Meeting their applications to rocketry. -

Nom De L'avion : Cams 37-2 Type D'avion : Hydravion D'observation Triplace MOTORISATION : Lorraine-Dietrich 12Ed

Nom de l'avion : Cams 37-2 Type d'avion : Hydravion d'observation triplace MOTORISATION : Lorraine-Dietrich 12Ed Moteur de 12 cylindres en V inversé refroidi par liquide Puissance développée: 1050 ch au décollage, 1100 ch à 3700 m et 2950 ch ARMEMENT 2 mitrailleuses Lewis en bossage 2 mitrailleuses Lewis en position dorsale 4 bombes de 75 kg sous les ailes PERFORMANCES Vitesse maximale= 175 km/h au niveau marin - 170 km/h à 2000 m Temps montée= 1000 m en 8' - 2000 m en 19' - 3000 m en 42' Plafond pratique= 3400 m Rayon action= 6h à 1000 m DIMENSIONS Envergure : 14,50 m Longueur : 11,45 m Hauteur : 4,20 m Surface alaire : 59,90 m2 MASSES Vide : 2170 kg Charge : 3000 kg Maximal : 3125 kg HISTOIRE Le CAMS 37 était un hydravion entre-deux guerres construit en France qui a vu le service répandu dans l'aéronavale française à la fois à la maison et à l'étranger. Au moins un exemple volait toujours dans une unité de Vichy en 1942. Bien que peut-être pas aussi connu que d'autres hydravions français tels que le Farman Goliath, le CAMS 55 ou le Breguet Bizerte, pratiquement tous les pilotes français de l'époque aurait volé un , le type en cours de déploiement dans les Antilles, l'Indo-Chine et Tahiti et à bord du navire. Conçu à l'origine pour la reconnaissance militaire, trois versions principales ont été produites en série et plus tard utilisées dans un certain nombre de rôles secondaires, y compris la liaison et de la formation. -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

For Peer Review Only

Ethnomusicology Forum For Peer Review Only Musical Cosmopolitanism in Late-Colonial Hanoi Journal: Ethnomusicology Forum Manuscript ID REMF-2017-0051.R1 Manuscript Type: Original Article Keywords: URL: http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/remf Page 1 of 40 Ethnomusicology Forum 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 For Peer Review Only 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 Figure 1 (see article text for complete caption) 46 47 179x236mm (300 x 300 DPI) 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 URL: http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/remf Ethnomusicology Forum Page 2 of 40 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 For Peer Review Only 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 Figure 2 (see article text for complete caption) 46 47 146x214mm (72 x 72 DPI) 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 URL: http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/remf Page 3 of 40 Ethnomusicology Forum 1 2 3 Musical Cosmopolitanism in Late-Colonial Hanoi 4 5 6 This article investigates how radio was used to amplify the reach of vernacular 7 forms of musical cosmopolitanism in late-colonial Hanoi. Between 1948 and the 8 9 early 1950s, the musicians of Việt Nhạc—the first allVietnamese ensemble to 10 appear regularly on Radio Hanoi—performed a unique blend of popular chansons 11 12 in Vietnamese and local folk styles live on air to a radio audience across French 13 Indochina. -

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by the Office Of

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by The Office of Communications and Records Department of State (Adopted January 1, 1950—Revised January 1, 1955) I I CLASSES OF RECORDS Glass 0 Miscellaneous. I Class 1 Administration of the United States Government. Class 2 Protection of Interests (Persons and Property). I Class 3 International Conferences, Congresses, Meetings and Organizations. United Nations. Organization of American States. Multilateral Treaties. I Class 4 International Trade and Commerce. Trade Relations, Treaties, Agreements. Customs Administration. Class 5 International Informational and Educational Relations. Cultural I Affairs and Programs. Class 6 International Political Relations. Other International Relations. I Class 7 Internal Political and National Defense Affairs. Class 8 Internal Economic, Industrial and Social Affairs. 1 Class 9 Other Internal Affairs. Communications, Transportation, Science. - 0 - I Note: - Classes 0 thru 2 - Miscellaneous; Administrative. Classes 3 thru 6 - International relations; relations of one country with another, or of a group of countries with I other countries. Classes 7 thru 9 - Internal affairs; domestic problems, conditions, etc., and only rarely concerns more than one I country or area. ' \ \T^^E^ CLASS 0 MISCELLANEOUS 000 GENERAL. Unclassifiable correspondence. Crsnk letters. Begging letters. Popular comment. Public opinion polls. Matters not pertaining to business of the Department. Requests for interviews with officials of the Department. (Classify subjectively when possible). Requests for names and/or addresses of Foreign Service Officers and personnel. Requests for copies of treaties and other publications. (This number should never be used for communications from important persons, organizations, etc.). 006 Precedent Index. 010 Matters transmitted through facilities of the Department, .1 Telegrams, letters, documents. -

The Mountain Is High, and the Emperor Is Far Away: States and Smuggling Networks at the Sino-Vietnamese Border

The Mountain Is High, and the Emperor Is Far Away: States and Smuggling Networks at the Sino-Vietnamese Border Qingfei Yin The intense and volatile relations between China and Vietnam in the dyadic world of the Cold War have drawn scholarly attention to the strategic concerns of Beijing and Hanoi. In this article I move the level of analysis down to the border space where the peoples of the two countries meet on a daily basis. I examine the tug-of-war between the states and smuggling networks on the Sino-Vietnamese border during the second half of the twentieth century and its implications for the present-day bilateral relationship. I highlight that the existence of the historically nonstate space was a security concern for modernizing states in Asia during and after the Cold War, which is an understudied aspect of China’s relations with Vietnam and with its Asian neighbors more broadly. The border issue between China and its Asian neighbors concerned not only territorial disputes and demarcation but also the establishment of state authority in marginal societies. Keywords: smuggler, antismuggling, border, Sino-Vietnamese relations, tax. Historically, the Chinese empire and, to a lesser extent, the Dai Nam empire that followed the Chinese bureaucratic model had heavyweight states with scholar-officials chosen by examination in the Confucian classics (Woodside 1971). However, as the proverb goes, the mountain is high, and the emperor is far away. Vast distances and weak connections existed between the central government and ordinary people. Central authorities thus had little influence over local affairs, including their own street-level bureaucracies. -

Occupation and Revolution

Occupation and Revolution . HINA AND THE VIETNAMESE ~-...uGUST REVOLUTION OF 1945 I o I o 1 I so lWoroeters -------uangTri ~ N I \\ Trrr1~ Sap Peter Worthing CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 54 CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 54 F M' INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES ~ '-" UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY C(5 CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES Occupation and Revolution China and the Vietnamese August Revolution of 1945 Peter Worthing A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of Califor nia, Berkeley. Although the Institute of East Asian Studies is responsible for the selection and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibil ity for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. Correspondence and manuscripts may be sent to: Ms. Joanne Sandstrom, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley, California 94720-2318 E-mail: [email protected] The China Research Monograph series is one of several publications series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. A list of recent publications appears at the back of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Worthing, Peter M. Occupation and revolution : China and the Vietnamese August revolu tion of 1945 I Peter M. Worthing. p. em. -(China research monograph; 54) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-55729-072-4 1. Vietnam-Politics and government-1858-1945. 2. Vietnam Politics and government-1945-1975. 3. World War, 1939-1945- Vietnam. -

Manila to Hanoi Flights Direct Avatar

Manila To Hanoi Flights Direct Attended and sterilized Thorvald generalised her obis dismembers while Jeffry disrates some inkwell cursedly. Fanned Quincey dislocating or inure some ockers rascally, however unsterile Lloyd mambos wakefully or gills. Hairlike and lightsome Orren address while select Hadleigh extracts her ichthyolatry soothfastly and heists perhaps. Reset your manila hanoi direct to all on the cheapest air and friends. Highest on the humidity is the online travel deals for a manila? Airport option available for manila to flights from manila in the item from hanoi in thousands of this email address is one of the visitors and schedule. Occurs in manila to manila flight fare for vietnam well in a travel entry restrictions and get updates on. Only show you to hanoi flights from manila are added fees are all major airlines fly from manila to accommodate you can expect three different choice of the dates? Hunt down your hanoi direct flights to vietnam choose specific hotel providers and get the departing dates, the precipitation are the document. Plenty of the event of east and preview manila to hanoi, or a specific hotel? Flying into another try logging you can reserve and dates? Allowing you to hanoi flights or with flexible with the ages of your visibility on average, so for airlines. Planning ahead is manila to hanoi flights from heathrow to get the flight. Love to manila to travellers from hanoi in vietnam is also book your next domestic flight fares and its advised to get the distance. Code is what are direct flights from manila to figure out at the list? Mall of hanoi are unbiased, hotel deals and check with one of flight search terms and stay. -

Air America in South Vietnam I – from the Days of CAT to 1969

Air America in South Vietnam I From the days of CAT to 1969 by Dr. Joe F. Leeker First published on 11 August 2008, last updated on 24 August 2015 I) At the times of CAT Since early 1951, a CAT C-47, mostly flown by James B. McGovern, was permanently based at Saigon1 to transport supplies within Vietnam for the US Special Technical and Economic Mission, and during the early fifties, American military and economic assistance to Indochina even increased. “In the fall of 1951, CAT did obtain a contract to fly in support of the Economic Aid Mission in FIC [= French Indochina]. McGovern was assigned to this duty from September 1951 to April 1953. He flew a C-47 (B-813 in the beginning) throughout FIC: Saigon, Hanoi, Phnom Penh, Vientiane, Nhatrang, Haiphong, etc., averaging about 75 hours a month. This was almost entirely overt flying.”2 CAT’s next operations in Vietnam were Squaw I and Squaw II, the missions flown out of Hanoi in support of the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu in 1953/4, using USAF C-119s painted in the colors of the French Air Force; but they are described in the file “Working in Remote Countries: CAT in New Zealand, Thailand-Burma, French Indochina, Guatemala, and Indonesia”. Between mid-May and mid-August 54, the CAT C-119s continued dropping supplies to isolated French outposts and landed loads throughout Vietnam. When the Communists incited riots throughout the country, CAT flew ammunition and other supplies from Hanoi to Saigon, and brought in tear gas from Okinawa in August.3 Between 12 and 14 June 54, CAT captain -

Marchofempire.Pdf

JIMMY SWAGGART BIBLE COLLEGE/SEMINARY LIBRARY ' . JIMMY SWAGGART BIBLE COLLEGE AND SEMINARY LIBRARY BATON ROUGE, LOUISIANA .. "' I l.J MARCH OF EMPIRE Af+td . .JV l cg s- Rg I '7 4 ~ MARCH OF EMPIRE The European Overseas Possessions on the Eve of the First World War By Lowell Ragatz, F .R.H.S. Professor of European History in The George Washington University Foreword by Alfred Martineau CASCADE COLLEGE LIBRARY H. L. LINDQUIST New York THE CANADIAN CHRISTMAS STAMP OF 1898, THE EPITOME OF MODERN IMPERIALISM. The phrase~ ~~we hold a vaster en1pire than has been," is excerpted from Jubilee Ode, by the Welsh poet, Sir Lewis Morris (1833 -1907). Copyright, 1948 By LOWELL RAGATZ PRJ NTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA To CauKo and PANCHO LIANG, Dear Friends of Long Ago FORE"\\TORD The period from the Fashoda Crisis to the outbreak of the great World War in 1914 has been generally neglected by specialists in European expansion. It is as though the several colonial empires had become static entities upon the close of the 19th century and that nothing of consequence had transpired in any of them in the decade and a half prior to the outbreak of that global struggle marking the end of an era in Modern Imperialism. Nothing is~ of course, farther fro~ the truth. I have, therefore, suggested to my former student and present colleague in the field of colonial studies, Professor Lowell Ragatz~ of The George Washington University in the United States, that he write a small volume filling this singular gap in the writings on modern empire building.