A Fig for Your Philosophy and Great Knowledge in the Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2216Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/150023 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications ‘AN ENDLESS VARIETY OF FORMS AND PROPORTIONS’: INDIAN INFLUENCE ON BRITISH GARDENS AND GARDEN BUILDINGS, c.1760-c.1865 Two Volumes: Volume I Text Diane Evelyn Trenchard James A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Warwick, Department of History of Art September, 2019 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………. iv Abstract …………………………………………………………………………… vi Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………. viii . Glossary of Indian Terms ……………………………………………………....... ix List of Illustrations ……………………………………………………………... xvii Introduction ……………………………………………………………………….. 1 1. Chapter 1: Country Estates and the Politics of the Nabob ………................ 30 Case Study 1: The Indian and British Mansions and Experimental Gardens of Warren Hastings, Governor-General of Bengal …………………………………… 48 Case Study 2: Innovations and improvements established by Sir Hector Munro, Royal, Bengal, and Madras Armies, on the Novar Estate, Inverness, Scotland …… 74 Case Study 3: Sir William Paxton’s Garden Houses in Calcutta, and his Pleasure Garden at Middleton Hall, Llanarthne, South Wales ……………………………… 91 2. Chapter 2: The Indian Experience: Engagement with Indian Art and Religion ……………………………………………………………………….. 117 Case Study 4: A Fairy Palace in Devon: Redcliffe Towers built by Colonel Robert Smith, Bengal Engineers ……………………………………………………..…. -

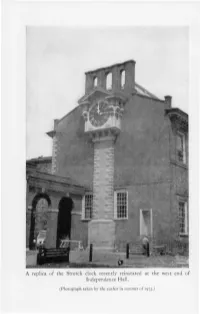

A Replica of the Stretch Clock Recently Reinstated at the West End of Independence Hall

A replica of the Stretch clock recently reinstated at the west end of Independence Hall. (Photograph taken by the author in summer of 197J.) THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY The Stretch Qlock and its "Bell at the State House URING the spring of 1973, workmen completed the construc- tion of a replica of a large clock dial and masonry clock D case at the west end of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the original of which had been installed there in 1753 by a local clockmaker, Thomas Stretch. That equipment, which resembled a giant grandfather's clock, had been removed in about 1830, with no other subsequent effort having been made to reconstruct it. It therefore seems an opportune time to assemble the scattered in- formation regarding the history of that clock and its bell and to present their stories. The acquisition of the original clock and bell by the Pennsylvania colonial Assembly is closely related to the acquisition of the Liberty Bell. Because of this, most historians have tended to focus their writings on that more famous bell, and to pay but little attention to the hard-working, more durable, and equally large clock bell. They have also had a tendency either to claim or imply that the Liberty Bell and the clock bell had been procured in connection with a plan to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary, or "Jubilee Year," of the granting of the Charter of Privileges to the colony by William Penn. But, with one exception, nothing has been found among the surviving records which would support such a contention. -

A Description of the Main Characters in the Movie the Greatest Showman

A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN A PAPER BY ELVA RAHMI REG.NO: 152202024 DIPLOMA III ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF CULTURE STUDY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH SUMATERA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I am ELVA RAHMI, declare that I am the sole author of this paper. Except where reference is made in the text of this paper, this paper contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a paper by which I have qualified for or awarded another degree. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of this paper. This paper has not been submitted for the award of another degree in any tertiary education. Signed : ……………. Date : 2018 i UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA COPYRIGHT DECLARATION Name: ELVA RAHMI Title of Paper: A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN. Qualification: D-III / Ahli Madya Study Program : English 1. I am willing that my paper should be available for reproduction at the discretion of the Libertarian of the Diploma III English Faculty of Culture Studies University of North Sumatera on the understanding that users are made aware of their obligation under law of the Republic of Indonesia. 2. I am not willing that my papers be made available for reproduction. Signed : ………….. Date : 2018 ii UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ABSTRACT The title of this paper is DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE GREATEST SHOWMAN MOVIE. The purpose of this paper is to find the main character. -

Joseph Saxton

MEMOIR OP JOSEPH SAXTON. 1799-1873. BY JOSEPH HENRY. HEAD BEFOEB THB NATIONAL ACADEMY, OCT. 4,1874. 28T BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF JOSEPH SAXTON. MR. PRESIDENT AND GENTLEMEN OF THE ACADEMY :— AT the last session of the National Academy of Sciences I was appointed to prepare an account of the life and labors of our lamented associate, Joseph Saxton, whose death we have been called to mourn. From long acquaintance and friendly relations with the deceased, the discharge of the duty thus devolved upon me has been a labor of love, but had he been personally unknown to me, the preparation of the eulogy would have been none the less a sacred duty, which I was not at liberty on any account to neglect. It is an obligation we owe to the Academy and the world to cherish the memory of our departed associates; their reputation is a precious inheritance to the Academy which exalts its character and extends its usefulness. Man is a sympathetic and imitative being, and through these characteristics of his nature the memories of good men produce an important influence on posterity, and therefore should be cherished and perpetuated. Moreover, the certainty of having a just tribute paid to our memory after our departure is one of the most powerful inducements to purity of life and propriety of deportment. The object of the National Academy is the advancement of science, and no one is considered eligible for membership who has not made positive additions to the sum of human knowledge, or in other words, has not done something to entitle him to the appellation of scientific. -

Superintendent's Annual Narrative Report, Independence National

Note the following: Page 15: Partnerships - “A challenge INDE faced in 2007 was finalizing long-term agreements with both the Independence Visitor Center Corporation (IVCC) and the National Constitution Center (NCC). Because of the complexity of these agreements, they are still under review in the Departments Office of the Solicitor. The IVCC and NCC continue to operate under Special Use Permits.” Page 16: Cooperating Agreement - “In 2007, INDE managed 12 Commercial Use Permits…The park successfully worked with the IVCC to respond to complaints from tour operators, who are competing for prime locations within the building to advertise their tours. While this problem will likely persist until the space within the Independence Visitor Center has been reorganized a project that will take place during 2008 through a series of meetings with the tour operators the park is continuing to address their concerns.” INDEPENDENCE NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK SUPERINTENDENT’S ANNUAL NARRATIVE REPORT October 1, 2006 – September 30, 2007 Introduction The Superintendent and staff of Independence National Historical Park (INDE) share the stewardship of some of the most important symbols of our nation’s heritage: the Liberty Bell, Independence Hall, Congress Hall and Franklin Court. They also share responsibility for Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site (EDAL), Thaddeus Kosciuszko National Memorial (THKO) and Gloria Dei (Old Swedes’) Church National Historic Site (GLDE). Independence National Historical Park continued to work on several multi-year, multi-faceted projects including the commemoration of the President’s House Site, the security plan for the Liberty Bell Center and Independence Square, the Long Range Interpretive Plan, the rehabilitation of Franklin Court and finalizing partnership agreements. -

The Forgotten Aquariums of Boston, Third Revised Edition by Jerry Ryan (1937 - )

THE FORGOTTEN AQUARIUMS OF BOSTON THIRD Revised Edition By Jerry Ryan 2011 Jerry Ryan All rights reserved. Excerpt from “For The Union Dead” from FOR THE UNION DEAD by Robert Lowell. Copyright 1959 by Robert Lowell. Copyright renewed 1987 by Harriet Lowell, Caroline Lowell and Sheridan Lowell. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. The Forgotten Aquariums of Boston, Third Revised Edition by Jerry Ryan (1937 - ). First Printing June, 2002. ISBN 0-9711999-0-6 (Softcover). 1.Public Aquaria. 2. Aquarium History. 3. Boston Aquarial Gardens. 4. Barnum’s Aquarial Gardens. 5. South Boston Aquarium. 6. P. T. Barnum. 7. James A. Cutting. 8. Henry D. Butler. 9. Aquariums. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface To The Third Revised Edition by Jeff Ives Page 6 Preface To The Second Edition By Jerry Ryan Page 7 Acknowledgements Page 9 The Boston Aquarial Gardens: Bromfield Street Page 10 Boston Aquarial and Zoological Gardens: Central Court Page 28 Barnum Aquarial Gardens Page 45 The South Boston Aquarium Page 62 Epilogue Page 73 Appendices Page 75 Illustration Credits Page 100 References and Suggested Reading Page 101 PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION Boston is known as a city filled with history, but it’s not always the history you’d expect. Today millions of tourists walk the freedom trail with Paul Revere’s famous ride galloping through their heads. Little do they know that 85 years after the fateful lamp was lit in Old North Church, an entirely different kind of ride was taking place in the heart of Boston’s Downtown Crossing. This ride was performed by a woman seated in a nautilus-shaped boat being pulled by a beluga whale through the largest tank in the first aquarium in the United States. -

Life of Hon. Phineas T. Barnum

Life of Hon. Phineas T. Barnum Joel Benton Life of Hon. Phineas T. Barnum Table of Contents Life of Hon. Phineas T. Barnum..............................................................................................................................1 Joel Benton.....................................................................................................................................................1 i Life of Hon. Phineas T. Barnum Joel Benton A UNIQUE STORY OF A MARVELLOUS CAREER. LIFE OF Hon. PHINEAS T. BARNUM. −−−− COMPRISING HIS BOYHOOD, YOUTH, ... CHAPTER I. IN THE BEGINNING. FAMILY AND BIRTH−−SCHOOL LIFE−−HIS FIRST VISIT TO NEW YORK CITY −−A LANDED PROPRIETOR−−THE ETHICS OF TRADE−−FARM WORK AND KEEPING STORE−−MEETING−HOUSE AND SUNDAY SCHOOL−−"THE ONE THING NEEDFUL." Among the names of great Americans of the nineteenth century there is scarcely one more familiar to the world than that of the subject of this biography. There are those that stand for higher achievement in literature, science and art, in public life and in the business world. There is none that stands for more notable success in his chosen line, none that recalls more memories of wholesome entertainment, none that is more invested with the fragrance of kindliness and true humanity. His career was, in a large sense, typical of genuine Americanism, of its enterprise and pluck, of its indomitable will and unfailing courage, of its shrewdness, audacity and unerring instinct for success. Like so many of his famous compatriots, Phineas Taylor Barnum came of good old New England stock. His ancestors were among the builders of the colonies of Massachusetts and Connecticut. His father's father, Ephraim Barnum, was a captain in the War of the Revolution, and was distinguished for his valor and for his fervent patriotism. -

A Tyranny of Documents: the Performing Arts Historian As Film Noir Detective

PERFORMING ARTS RESOURCES VOLUME TWENTY-EIGHT A Tyranny of Documents: The Performing Arts Historian as Film Noir Detective Essays Dedicated to Brooks McNamara Edited by Stephen Johnson Published by the Theatre Library Association Published by Theatre Library Association Copyright 2011 by Theatre Library Association Headquarters: c/o The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, 40 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, New York 10023 Website: http://www.tla-online.org/ Membership dues: $30 personal; $20 students/non-salaried; $40 institutional The articles in this volume have been copyrighted by their authors. The Library of Congress catalogued this serial as follows: Performing Arts Resources Vols. for 1974—issued by the Theatre Library Association ISSN 03603814 1. Performing arts—Library resources—United States—Periodicals I. Theatre Library Association Z6935.P46 016.7902’08 75–646287 ISBN 978-0-932610-24-9. Theatre Library Association has been granted permission to reproduce all illustrations in this volume. Front cover image: For credit information on the collage imagery, see the full illustrations in this volume on pp 16, 33, 102, 111, 129, 187, 196, 210, 218, 254 Cover and page design: Sans Serif, Saline, Michigan Printed by McNaughton and Gunn, Saline Michigan Manufactured in the United States of America This serial is printed on acid-free paper. Barnum’s Last Laugh? General Tom Thumb’s Wedding Cake in the Library of Congress1 MARLIS SCHWEITZER In most if not all archives, food is strictly prohibited. This is certainly the case at the Library of Congress, where researchers entering the Manuscript Read- ing Room are required to place all personal belongings in specially desig- nated lockers and present all pencils, papers, computers, and cameras to a guard before gaining admittance to the room. -

May 2011, Vol. 37 No. 2

· Oseph & Merry Weather's adventure --- Gass descendant's grave discovered Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation I www.lewisandclark.org May 2011 Volume 37, No. 2 THE L&C EXPEDITION'S ''MACKENZIE CONNECTION'' - RA01sSON AND GROSSEILLJERs · (1905), av FREDERICK REMINGTON T HE C ORPS OF DISCOVERY AND THE A RTICLES OF WAR FuRTWANGLER ON J ouRNAL C OPYING AT T RAVELER'S R EST Contents Letters: Gass grandson's grave found 2 President's Message: Busy winter, promising spring 4 Trail Notes: Simple questions, complicated answers 5 Voyages from Montreal 6 How Alexander Mackenzie's 1793 trans-Canada crossing influenced the Lewis and Clark Expedition By H. Cad Camp Journal Copying at Travelers· Rest 14 Comparing the journals of Gass, Ordway, and Whitehouse with those of Lewis and Clark reveals many similarities-and some important differences By Alburt Furtwangler Mackenzie, p. 7 Lewis & Clark and the Articles of War 21 Out of necessity, the captains developed their own harsh but effective system of military justice By William M. Gadin Kids' Corner 28 Oseph of the Corps of Discovery By Betty Bauer ' L&CRoundup 31 N.D. interpretive center; Undaunted Angl~i;s _ :. "\ < Profile . 32 Isaiah Lukens: Mechanical Genius By Michael Carrick Ordway, p. 15 On the cover This majestic painting by Frederick Remington depicts the French explorers Pierre-Esprit Radisson (1636-1710) and his brother-in-law Medard des Grosseilliers {1618-1696) plying wilderness waters1n a canot du maitre ("master's canoe"), the workhorse of the Canadian fur trade. In J. 793, more than a century after Radisson and Grosseilliers and 10 years before Lewis and Clark, the Scottish explorer and fur trader Alexander Mackenzie made use of a canot du maitre in his crossing of the continent. -

November 2002, Vol. 28 No. 4

Contents Letters: Bad River encounter; Crimson Bluffs 2 From the Directors: Spreading the word in Two Med country 3 From the Bicentennial Council: L&C from different perspectives 4 Trail Notes: Eyes and ears along the Lewis & Clark Trail 6 Tales of the Variegated Bear 8 The captains scoffed at the Mandans’ reports of its ferocity — until they tangled with the “turrible” beast on the high Missouri By Kenneth C. Walcheck Grizzlies, p. 8 Meriwether Lewis’s Air Gun 15 His pneumatic wonder amazed the Indians — but was it a single shot weapon or, as new evidence suggests, a repeater? By Michael F. Carrick Neatness Mattered 22 Hair, beards, and the Corps of Discovery By Robert J. Moore, Jr. The Utmost Reaches of the Missouri 29 Two latter-day explorers describe their quest for the river’s “distant fountain,” 100 miles southeast of Lemhi Pass By Donald F. Nell and Anthony Demetriades Reviews 34 Gunmaker Isaiah Lukens, p. 15 Lewis and Clark among the Grizzlies; Or Perish in the Attempt In Brief: Wheeler, McMurtry, Gass, Best Little Stories L&C Roundup 38 New leadership; kudos; President Bush on Corps of Discovery Gary Moulton’s White House remarks 44 Annual meeting photo spread: Louisville, July 2002 48 On the cover John F. Clymer’s painting Hasty Retreat dramatically depicts one of the many encounters between members of the Corps of Discovery and grizzly bears on the upper Missouri. For more on the explorers’ travails with the variegated bear, see Kenneth Walcheck’s article beginning on page 8 and the review of Paul Schullery’s new book on page 34. -

Appendix I P. T. Barnum: Humbug and Reality

APPENDIX I P. T. BARNUM: HUMBUG AND REALITY s a candidate for the father of American show business, Barnum’s Awider significance is still being quarried by those with an interest in social and cultural history. The preceding chapters have shown how vari- ety, animal exhibits, circus acts, minstrelsy, and especially freak shows, owe much of their subsequent momentum to his popularization of these amusement forms. For, while Barnum has long been associated in popular memory solely with the circus business, his overall career as an entertainment promoter embraced far more than the celebrated ringmas- ter figure of present-day public estimation. Barnum saw himself as “the museum man” for the better part of his long show business career, following his successful management of the American Museum from the 1840s to the 1860s. To repeat, for all Barnum’s reputation today as a “circus man,” he saw himself first and foremost as a museum proprietor, one who did much to promote and legitimize the display of “human curiosities.”1 While the emergence of an “American” national consciousness has been dated to the third quarter of the eighteenth century, Barnum’s self- presentation was central to the cultural formation of a particular middle- class American sense of identity in the second half of the nineteenth century (see chapter 1), as well as helping to shape the new show business ethos. Over time, he also became an iconic or referential figure in the wider culture, with multiple representations in cinematic, theatrical, and literary form (see below).Yet was Barnum really the cultural pacesetter as he is often presented in popular biographical writing, not to mention his own self-aggrandizing prose. -

The American Air Gun School of 1800-1830 By: H

The American Air Gun School of 1800-1830 by: H. M. Stewart When the Pilgrims stepped on the Rock in 1620 did they :arry those blunderbusses we see pictured? How about air :uns? My expert friend, Chuck Suydam, joins most of us n ruling out the blunderbuss, but there could have been iir guns. Marin Le Bourgeoys of Lisieux, France, demon- itrated his air gun to Henry I1 of Navarre in 1602. At the 1976 Valley Forge ASAC meeting practically all the active nterested members were present for my discussion on 'hiladelphia air guns. I spent nearly an hour covering the ~riorstate of the art, the types of arms, and, what mpressed them most, the deadly efficiency of these early Neapons. They were not the BB rifle you played with as a tid: these penetrated 2% inches of pine while the Kentucky ifle, in comparison, did 2% inches! For those of you who ~ouldhave liked to be at Valley Forge, I recommend <ldon Wolff's AIR GUNS for this background. In particu- ar, I urge Dr. Jim, who sent me the BB marksman's button o alibi his New Orleans Anesthesic Adventure, that this )e required reading! Most of the guns physically used in The second publicity of the air gun in my context is the ny talk are pictured in Eldon's AIR GUNS, which is Girardini Austrian military model of 1780 with its bullet ~btainablefrom the Milwaukee Museum for a few dollars. magazine for 20 balls on the right side of the barrel breech. ;pace in the JOURNAL will be saved if you read and I chose as my example of this a model by M.