Appendix I P. T. Barnum: Humbug and Reality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Monkey's Tale

A Monkey’s Tale P.T. Barnum - a most remarkable showman There were also living exhibits at his Ameri- in 19th century America began his career can Museum. Barnum exhibited a four-year- long before his famous circus was created old boy who stood 25 inches high. This boy in 1872. In January 1842, Barnum opened famously became known as General Tom his American Museum in New York. The Thumb, or Man in Miniature, who Barnum Museum was promoted as a place for billed as an eleven-year-old. New York was family entertainment, enlightenment and fascinated by Tom Thumb and his popular- amusement. ity encouraged Barnum to arrange a tour around England where the company was From 1842 until 1865, the American Museum given an audience of Queen Victoria, the grew into an enormous enterprise. Barnum’s royal family and many heads of states. cryptozoology department in particular gained a lot of attention, from when he introduced his first major hoax: a creature with the head of a monkey and the tail of a fish, known as the “Feejee” mermaid. The Museum also contained a wax-figure department which produced likenesses of notable personalities of the day, an aquarium and a taxidermy department. A Monkey’s Tale The circus which P.T. Barnum is famous for Barnum’s Mandrill was his retirement project. Barnum was already a well-established entertainer but Barnum and Bailey’s Circus travelled in four at 61 years old he began the “Greatest trains of 15 coaches, with most of the car- Show on Earth”. -

By Alyssa Chan Gangster Or Entrepreneur?

Reggie Kray By Alyssa Chan Gangster or Entrepreneur? Employed Entrepreneurial Behaviour Entrepreneurial Theory Alvarez (2007) suggested that entrepreneurial opportunities can be Reggie Kray’s unquestionable influence helped him to acquire The word entrepreneur is derived from the French entreprendre, exploited in a variety of ways conveying the idea that the most several pubs and clubs across the city, during what was known as which means “to undertake. Someone who undertakes the tasks efficient way to exploit a particular opportunity is by organising an “the swinging sixties”. Reggie’s clever utilisation of his entrepreneurial of organising, managing and assuming the risks of businesses enterprise. Reggie Kray does exactly that and can thus be classified skills and charm allowed this club to thrive with rich and famous (Webster 2020) However, there is no singular definition of the as one of the most successful entrepreneurs of the illegal world, clientele joining the twins each week, making them a handsome term entrepreneur . According to Kuratko (2017)) the profit. They were seen socialising with MPs, lords and several characteristics and actions of entrepreneurs, such as seeking conveying tactical entrepreneurial behaviour. opportunities, taking risks and enabling their tenacity to develop celebrities, increasing the Kray’s influence and enriching their their idea combine into a special mindset of entrepreneurs. Reggie planned and plotted to build his criminal empire from a young celebrity status (Lambrianou, 1991.). age. Reggie produced the idea to run protection rackets for local It is impossible to categorise all entrepreneurs due to the broad businesses, using his ruthless and violent reputation to his After the imprisonment and eventual downfall of the Kray’s, their definition. -

Archiving Possibilities with the Victorian Freak Show a Dissertat

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE “Freaking” the Archive: Archiving Possibilities With the Victorian Freak Show A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ann McKenzie Garascia September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Joseph Childers, Co-Chairperson Dr. Susan Zieger, Co-Chairperson Dr. Robb Hernández Copyright by Ann McKenzie Garascia 2017 The Dissertation of Ann McKenzie Garascia is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation has received funding through University of California Riverside’s Dissertation Year Fellowship and the University of California’s Humanities Research Institute’s Dissertation Support Grant. Thank you to the following collections for use of their materials: the Wellcome Library (University College London), Special Collections and University Archives (University of California, Riverside), James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center (San Francisco Public Library), National Portrait Gallery (London), Houghton Library (Harvard College Library), Montana Historical Society, and Evanion Collection (the British Library.) Thank you to all the members of my dissertation committee for your willingness to work on a project that initially described itself “freakish.” Dr. Hernández, thanks for your energy and sharp critical eye—and for working with a Victorianist! Dr. Zieger, thanks for your keen intellect, unflappable demeanor, and ready support every step of the process. Not least, thanks to my chair, Dr. Childers, for always pushing me to think and write creatively; if it weren’t for you and your Dickens seminar, this dissertation probably wouldn’t exist. Lastly, thank you to Bartola and Maximo, Flora and Martinus, Lalloo and Lala, and Eugen for being demanding and lively subjects. -

Tom Thumb Comes to Town

TOM THUMB COMES TO TOWN By Marianne G. Morrow The Performance Tom Thumb had already performed twice in Hali- ver the years, the city of Char- fax, in 1847 and 1850, O lottetown has had many exotic but he had never come visitors, from British royalty t o gangsters. to Prince Edward Perhaps the most unusual, though, was Island. His visit in 1868 the celebrated "General" Tom Thumb probably followed a set and his troupe of performers. On 30 July pattern. The group's 1868, Tom Thumb, his wife Lavinia "Director of Amuse- Warren, her sister Minnie, and "Commo- ments" was one Sylvester dore" Nutt arrived fresh from a European Bleecker, but advance pub- tour to perform in the Island capital's licity was handled by a local Market Hall. agent, Ned Davies. There Tom Thumb was a midget, as would be five performances were the other members of his com- spread over a two-day period. pany. Midgets differ from dwarfs in "Ladies and children are con- that they are perfectly proportioned siderately advised to attend the beings, "beautiful and symmetri- Day exhibition, and thus avoid cally formed ladies and gentlemen the crowd and confusion of the in miniature," as the ads for evening performances." Thumb's performance promised. S The pitch was irresistible. What society considered a disability, \ "The Smallest Human Beings of Tom Thumb had managed to turn 1 Mature Age Ever Known on the into a career. By the time he arrived S Face of the Globe!" boasted one on Prince Edward Island, he had been 4 ad. -

Winter 2021 January – April BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING JANUARY 2021

BLOOMSBURY Winter 2021 January – April BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING JANUARY 2021 A Court of Silver Flames Sarah J. Maas The fourth book in the Court of Thorns and Roses series from #1 global bestseller Sarah J. Maas. The fourth book in the Court of Thorns and Roses series from #1 global bestseller Sarah J. Maas. PRAISE for ACOTAR "Simply dazzles." —Booklist, starred review "Passionate, violent, sexy and daring . A true page-turner." —USA Today "Suspense, romance, intrigue and action. This is not a book to be missed!" FICTION / FANTASY / ROMANTIC —HuffPost Bloomsbury Publishing | 1/26/2021 "Vicious and intoxicating . A dazzling world, complex characters, and sizzling 9781681196282 | $28.00 / $38.00 Can. romance." —RT Book Reviews, Top Pick Hardcover with dust jacket | 648 pages 9.3 in H | 6.1 in W "A sexy, action-packed fairy tale." —Bustle for ACOMAF "Fiercely romantic, irresistibly sexy and hypnotically magical. A veritable feast for the senses." —USA Today MARKETING Major prepublication buzz-building "Hits the spot for fans of dark, lush, sexy fantasy." —Kirkus Reviews campaign starting 8 months prepub "An immersive, satisfying read." —PW Social media campaign to include title and "Darkly sexy and thrilling." —Bustle cover reveals, sneak peaks, character quotes, animated trailer and more for ACOWAR Exclusive swag item available at NY "Fast... ComicCon 2020 Global preorder offer launching several months before publication SARAH J. MAAS is the #1 New York Times and internationally bestselling author of the Court of YouTube live author appearances teasing Thorns and Roses and the Crescent City series, as well as the Throne of Glass series. -

He Tiarral= Wheeler House SMITHSONIAN STUDIES in HISTORY and TECHNOLOGY J NUMBER 18

BRIDGEPORT'S GOTHIC ORNAMENT / he tiarral= Wheeler House SMITHSONIAN STUDIES IN HISTORY AND TECHNOLOGY J NUMBER 18 BRIDGEPORT'S GOTHIC ORNAMENT / he Harral= Wheeler Hiouse Anne Castrodale Golovin SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS { CITY OF WASHINGTON \ 1972 Figure i. An 1850 map of Bridgeport, Connecticut, illustrating in vignettes at the top right and left corners the Harral House and P. T. Barnum's "Oranistan." Arrow in center shows location of Harral House. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) Ems^m^wmy^' B m 13 ^»MMaM««^fc mwrtkimmM LMPOSING DWELLINGS in the Gothic Revival style were among the most dramatic symbols of affluence in mid-nineteenth-century America. With the rise of industrialization in this periods an increasing number of men from humble beginnings attained wealth and prominence. It was impor tant to them as well as to gentlemen of established means that their dwell ings reflect an elevated social standing. The Harral-Wheeler residence in Bridgeport, Connecticut, was an eloquent proclamation of the success of its owners and the excellence of the architect Alexander Jackson Davis. Al though the house no longer stands, one room, a selection of furniture, orig inal architectural designs, architectural fragments, and other supporting drawings and photographs are now in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution. These remnants of Bridgeport's Gothic "ornament" serve as the basis for this study. AUTHOR.—Anne Castrodale Golovin is an associ ate curator in the Department of Cultural History in the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of History and Technology. B>RIDGEPORT, , CONNECTICUT, was fast be speak of the Eastern glories of Iranistan, we have coming a center of industry by the middle of the and are to have in this vicinity, many dwelling- nineteenth century; carriages, leather goods, and houses worthy of particular notice as specimens of metal wares were among the products for which it architecture. -

Barnum Museum, Planning to Digitize the Collections

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the NEH Division of Preservation and Access application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/preservation/humanities-collections-and-reference- resources for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Preservation and Access staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Planning for "The Greatest Digitization Project on Earth" with the P. T. Barnum Collections of The Barnum Museum Foundation Institution: Barnum Museum Project Director: Adrienne Saint Pierre Grant Program: Humanities Collections and Reference Resources 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 411, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8570 F 202.606.8639 E [email protected] www.neh.gov The Barnum Museum Foundation, Inc. Application to the NEH/Humanities Collections and Reference Resources Program Narrative Significance Relevance of the Collections to the Humanities Phineas Taylor Barnum's impact reaches deep into our American heritage, and extends far beyond his well-known circus enterprise, which was essentially his “retirement project” begun at age sixty-one. -

Five Points Book by Harrison David Rivers Music by Ethan D

Please join us for a Post-Show Discussion immediately following this performance. Photo by Allen Weeks by Photo FIVE POINTS BOOK BY HARRISON DAVID RIVERS MUSIC BY ETHAN D. PAKCHAR & DOUGLAS LYONS LYRICS BY DOUGLAS LYONS DIRECTED BY PETER ROTHSTEIN MUSIC DIRECTION BY DENISE PROSEK CHOREOGRAPHY BY KELLI FOSTER WARDER WORLD PREMIERE • APRIL 4 - MAY 6, 2018 • RITZ THEATER Theater Latté Da presents the world premiere of FIVE POINTS Book by Harrison David Rivers Music by Ethan D. Pakchar & Douglas Lyons Lyrics by Douglas Lyons Directed by Peter Rothstein** Music Direction by Denise Prosek† Choreography by Kelli Foster Warder FEATURING Ben Bakken, Dieter Bierbrauer*, Shinah Brashears*, Ivory Doublette*, Daniel Greco, John Jamison, Lamar Jefferson*, Ann Michels*, Thomasina Petrus*, T. Mychael Rambo*, Matt Riehle, Kendall Anne Thompson*, Evan Tyler Wilson, and Alejandro Vega. *Member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors ** Member of SDC, the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, a national theatrical labor union †Member of Twin Cities Musicians Union, American Federation of Musicians FIVE POINTS will be performed with one 15-minute intermission. Opening Night: Saturday, April 7, 2018 ASL Interpreted and Audio Described Performance: Thursday, April 26, 2018 Meet The Writers: Sunday, April 8, 2018 Post-Show Discussions: Thursdays April 12, 19, 26, and May 3 Sundays April 11, 15, 22, 29, and May 6 This production is made possible by special arrangement with Marianne Mills and Matthew Masten. The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. As a courtesy to the performers and other patrons, please check to see that all cell phones, pagers, watches, and other noise-making devices are turned off. -

A Description of the Main Characters in the Movie the Greatest Showman

A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN A PAPER BY ELVA RAHMI REG.NO: 152202024 DIPLOMA III ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF CULTURE STUDY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH SUMATERA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I am ELVA RAHMI, declare that I am the sole author of this paper. Except where reference is made in the text of this paper, this paper contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a paper by which I have qualified for or awarded another degree. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of this paper. This paper has not been submitted for the award of another degree in any tertiary education. Signed : ……………. Date : 2018 i UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA COPYRIGHT DECLARATION Name: ELVA RAHMI Title of Paper: A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN. Qualification: D-III / Ahli Madya Study Program : English 1. I am willing that my paper should be available for reproduction at the discretion of the Libertarian of the Diploma III English Faculty of Culture Studies University of North Sumatera on the understanding that users are made aware of their obligation under law of the Republic of Indonesia. 2. I am not willing that my papers be made available for reproduction. Signed : ………….. Date : 2018 ii UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ABSTRACT The title of this paper is DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE GREATEST SHOWMAN MOVIE. The purpose of this paper is to find the main character. -

FIST STICK KNIFE GUN a Personal History of Violence Author Website: by Geoffrey Canada

Academic Marketing Dept. • 1745 Broadway • New York, NY 10019 Random House, Inc. Tel: 212-782-8482 • Fax: 212-782-8915 • ) [email protected] CONTENTS FEaturEd titlEs subjEct catEgoriEs THE OXFORD PROJECT By Stephen G. Bloom and Peter Feldstein ............................2–3 CULTURAL / ETHNIC STUDIES THE SOCIAL ANIMAL By David Brooks ......................................................................4–5 Anthropology ................................................................................................................34 FIST, STICK, KNIFE, GUN By Geoffrey Canada ..........................................................6–7 American Studies ....................................................................................................34–35 HOLLOWING OUT THE MIDDLE By Patrick J. Carr and Maria J. Kefalas ....................8–9 Ethnomusicology ..........................................................................................................35 I DON’T WISH NOBODY TO HAVE A LIFE LIKE MINE By David Chura ................10–11 African / African American Studies ..........................................................................35–36 THE AGE OF EMPATHY By Frans de Waal ..............................................................12–13 Asian Studies..................................................................................................................36 OCCULT AMERICA By Mitch Horowitz....................................................................14–15 Latino / Latina Studies....................................................................................................36 -

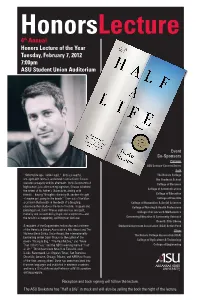

4Th Annual Honors Lecture of the Year Tuesday, February 7, 2012 7:00Pm ASU Student Union Auditorium

Honors Lecture 4th Annual Honors Lecture of the Year Tuesday, February 7, 2012 7:00pm ASU Student Union Auditorium Event Co-Sponsors Platinum ASU Lecture-Concert Series Gold “Half my life ago, I killed a girl.” In this powerful, The Honors College unforgettable memoir, acclaimed novelist Darin Strauss The Graduate School recounts a tragedy and its aftermath. In his last month of College of Business high school, just after turning eighteen, Strauss is behind College of Communications the wheel of his father's Oldsmobile, driving with friends—having “thoughts of mini-golf, another thought College of Education of maybe just going to the beach.” Then out of the blue: College of Fine Arts a collision that results in the death of a bicycling College of Humanities & Social Sciences classmate that shadows the rest of his life. In spare and College of Nursing & Health Professions piercing prose, Darin Strauss explores loss and guilt, College of Sciences & Mathematics maturity and accountability, hope and acceptance—and the result is a staggering, uplifting tour de force. Continuing Education & Community Outreach Dean B. Ellis Library A recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship and a winner Student Government Association (SGA) Action Fund of the American Library Association's Alix Award and The Silver National Book Critics Circle Award, the internationally- The Honors College Association (HCA) bestselling writer Darin Strauss is the author of the novels “Chang & Eng,” “The Real McCoy,” and “More College of Agriculture & Technology Than It Hurts You,” and the NBCC-winning memoir “Half College of Engineering a Life.” These have been New York Times Notable Books, Newsweek, Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Amazon, Chicago Tribune, and NPR Best Books of the Year, among others. -

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10244)018 (Rev. M6) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name MAPLEWOOD SCHOOL other names/site number Grammar School No. 5 2. Location street & number 434 Maplewood Avenue N/A' not for publication city, town Bridgeport N/AL. v«c'nity state Connecticut code CT county Fairfield code 001 zip code 06605 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property I private X building(s) Contributing Noncontributing "xl public-local district 2 ____ buildings HI public-State site ____ sites I I public-Federal structure ____ structures EH object ____ objects ____Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A listed in the National Register 0 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this EX] nomination EH request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60.