Archiving Possibilities with the Victorian Freak Show a Dissertat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Be-Hold October 29, 2016 Auction Results Lot Item

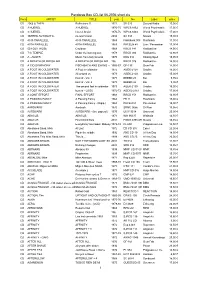

BE-HOLD OCTOBER 29, 2016 AUCTION RESULTS updated 12/4/2016 Lots with prices in red are the auction winning bids. Lots sold after the auction are in blue. Those with no price are still available for a limited time - photos of each may be seen through the Auction site link (to the left of Auction Results). Please contact Be-hold directly for prices. LOT ITEM START SOLD 1 RR Depot at Warrenton $ 120 $ 260 2 Ruins of Hampton Church $ 90 $ 100 3 View in Culpepper VA $ 140 $ 140 4 Three Views $ 120 $ 260 5 Ruins of bridge at Mrs. Nelson's $ 50 $ 150 6 Wounded, at Savage Station $ 150 $ 260 7 Confederate Dead $ 200 $ 390 8 Council of War $ 30 $ 160 9 Brady at Harper's Ferry $ 120 $ 360 10 Docks, Batteries, Breastworks $ 70 $ 260 11 Charles City Court House $ 140 $ 240 12 Quarles Mill, North Anna $ 60 $ 120 13 North Anna $ 100 $ 300 14 Cedar Mountain $ 20 $ 85 15 Battery Near Yorktown $ 40 $ 60 16 Parson Slaughter's House $ 40 $ 100 17 Matthew's House $ 90 $ 220 18 Elliston's Mill, by Gardner $ 90 - 19 Winter Quarters Confederate Army $ 100 $ 220 20 Farnhold's House $ 80 $ 280 21 Former Slaves at Fair Oaks $ 100 $ 280 22 Two Views by O'Sullivan and Barnard $ 60 $ 140 23 Five CDVs from Brady's Album Gallery $ 200 $ 390 24 Church Ruins at Hampton $ 140 $ 180 25 Vew of an Encampment on Banks of River $ 120 - 26 Encampment at Farm About the River $ 100 - 27 Richmond Ruins, 1865 $ 40 $ 40 28 USA Laboratory $ 30 $ 30 29 Philadelphia Photographer $ 1,500 $ 1,250 30 Photograph Competing for Gold Medal $ 60 $ 120 31 Large Camera Takes Our Picture $ 300 -

Pandoras Box CD-List 06-2006 Short

Pandoras Box CD-list 06-2006 short.xls Form ARTIST TITLE year No Label price CD 2066 & THEN Reflections !! 1971 SB 025 Second Battle 15,00 € CD 3 HUEREL 3 HUEREL 1970-75 WPC6 8462 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3 HUEREL Huerel Arisivi 1970-75 WPC6 8463 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3SPEED AUTOMATIC no man's land 2004 SA 333 Nasoni 15,00 € CD 49 th PARALLELL 49 th PARALLELL 1969 Flashback 008 Flashback 11,90 € CD 49TH PARALLEL 49TH PARALLEL 1969 PACELN 48 Lion / Pacemaker 17,90 € CD 50 FOOT HOSE Cauldron 1968 RRCD 141 Radioactive 14,90 € CD 7 th TEMPLE Under the burning sun 1978 RRCD 084 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A - AUSTR Music from holy Ground 1970 KSG 014 Kissing Spell 19,95 € CD A BREATH OF FRESH AIR A BREATH OF FRESH AIR 196 RRCD 076 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A CID SYMPHONY FISCHBACH AND EWING - (21966CD) -67 GF-135 Gear Fab 14,90 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER A Foot in coldwater 1972 AGEK-2158 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER All around us 1973 AGEK-2160 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 1 1973 BEBBD 25 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 2 1973 BEBBD 26 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER The second foot in coldwater 1973 AGEK-2159 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - (2CD) 1972-73 AGEK2-2161 Unidisc 17,90 € CD A JOINT EFFORT FINAL EFFORT 1968 RRCD 153 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy 1968 FB 11 Flashback 15,00 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy - (Digip.) 1968 PACE-034 Pacemaker 15,90 € CD AARDVARK Aardvark 1970 SRMC 0056 Si-Wan 19,95 € CD AARDVARK AARDVARK - (lim. -

Ghost Signs Are More Than Paintings on Brick

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2020 ghost signs are more than paintings on brick Eric Anthony Berdis Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons © Eric Anthony Berdis Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/6287 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©2020 All Rights Reserved ghost signs are more than paintings on brick A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University Eric Anthony Berdis B.F.A. Slippery Rock University, 2013 Post-baccalaureate Tyler School of Art, 2016 M.F.A. Virginia Commonwealth University, 2020 Director: Hillary Waters Fayle Assistant Professor- Fiber and Area Head of Fiber Craft/ Material Studies Department Jack Wax Professor - Glass and Area Head of Glass Craft/ Material Studies Department Kelcy Chase Folsom Assistant Professor - Clay Craft/ Material Studies Department Dr. Tracy Stonestreet Graduate Faculty Craft/ Material Studies Department v Acknowledgments Thank you to my amazing studio mate Laura Boban for welcoming me into your life, dreams, and being a shoulder of support as we walk on this journey together. You have taught me so much and your strength, thoughtfulness, and empathy make me both grateful and proud to be your peer. Thank you to Hillary Fayle for the encouragement, your critical feedback has been imperative to my growth. -

The John and Anna Gillespie Papers an Inventory of Holdings at the American Music Research Center

The John and Anna Gillespie papers An inventory of holdings at the American Music Research Center American Music Research Center, University of Colorado at Boulder The John and Anna Gillespie papers Descriptive summary ID COU-AMRC-37 Title John and Anna Gillespie papers Date(s) Creator(s) Repository The American Music Research Center University of Colorado at Boulder 288 UCB Boulder, CO 80309 Location Housed in the American Music Research Center Physical Description 48 linear feet Scope and Contents Papers of John E. "Jack" Gillespie (1921—2003), Professor of music, University of California at Santa Barbara, author, musicologist and organist, including more than five thousand pieces of photocopied sheet music collected by Dr. Gillespie and his wife Anna Gillespie, used for researching their Bibliography of Nineteenth Century American Piano Music. Administrative Information Arrangement Sheet music arranged alphabetically by composer and then by title Access Open Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the American Music Research Center. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], John and Anna Gillespie papers, University of Colorado, Boulder Index Terms Access points related to this collection: Corporate names American Music Research Center - Page 2 - The John and Anna Gillespie papers Detailed Description Bibliography of Nineteenth-Century American Piano Music Music for Solo Piano Box Folder 1 1 Alden-Ambrose 1 2 Anderson-Ayers 1 3 Baerman-Barnes 2 1 Homer N. Bartlett 2 2 Homer N. Bartlett 2 3 W.K. Bassford 2 4 H.H. Amy Beach 3 1 John Beach-Arthur Bergh 3 2 Blind Tom 3 3 Arthur Bird-Henry R. -

The Caffe Cino

DESIGNATION REPORT The Caffe Cino Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 DESIGNATION REPORT The Caffe Cino LOCATION Borough of Manhattan 31 Cornelia Street LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE No. 31 Cornelia Street in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan is culturally significant for its association with the Caffe Cino, which occupied the building’s ground floor commercial space from 1958 to 1968. During those ten years, the coffee shop served as an experimental theater venue, becoming the birthplace of Off-Off-Broadway and New York City’s first gay theater. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 Former location of the Caffe Cino, 31 Cornelia Street 2019 LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Lisa Kersavage, Executive Director Sarah Carroll, Chair Mark Silberman, Counsel Frederick Bland, Vice Chair Kate Lemos McHale, Director of Research Diana Chapin Cory Herrala, Director of Preservation Wellington Chen Michael Devonshire REPORT BY Michael Goldblum MaryNell Nolan-Wheatley, Research Department John Gustafsson Anne Holford-Smith Jeanne Lutfy EDITED BY Adi Shamir-Baron Kate Lemos McHale and Margaret Herman PHOTOGRAPHS BY LPC Staff Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 3 of 24 The Caffe Cino the National Parks Conservation Association, Village 31 Cornelia Street, Manhattan Preservation, Save Chelsea, and the Bowery Alliance of Neighbors, and 19 individuals. No one spoke in opposition to the proposed designation. The Commission also received 124 written submissions in favor of the proposed designation, including from Bronx Borough President Reuben Diaz, New York Designation List 513 City Council Member Adrienne Adams, the LP-2635 Preservation League of New York State, and 121 individuals. -

He Tiarral= Wheeler House SMITHSONIAN STUDIES in HISTORY and TECHNOLOGY J NUMBER 18

BRIDGEPORT'S GOTHIC ORNAMENT / he tiarral= Wheeler House SMITHSONIAN STUDIES IN HISTORY AND TECHNOLOGY J NUMBER 18 BRIDGEPORT'S GOTHIC ORNAMENT / he Harral= Wheeler Hiouse Anne Castrodale Golovin SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS { CITY OF WASHINGTON \ 1972 Figure i. An 1850 map of Bridgeport, Connecticut, illustrating in vignettes at the top right and left corners the Harral House and P. T. Barnum's "Oranistan." Arrow in center shows location of Harral House. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) Ems^m^wmy^' B m 13 ^»MMaM««^fc mwrtkimmM LMPOSING DWELLINGS in the Gothic Revival style were among the most dramatic symbols of affluence in mid-nineteenth-century America. With the rise of industrialization in this periods an increasing number of men from humble beginnings attained wealth and prominence. It was impor tant to them as well as to gentlemen of established means that their dwell ings reflect an elevated social standing. The Harral-Wheeler residence in Bridgeport, Connecticut, was an eloquent proclamation of the success of its owners and the excellence of the architect Alexander Jackson Davis. Al though the house no longer stands, one room, a selection of furniture, orig inal architectural designs, architectural fragments, and other supporting drawings and photographs are now in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution. These remnants of Bridgeport's Gothic "ornament" serve as the basis for this study. AUTHOR.—Anne Castrodale Golovin is an associ ate curator in the Department of Cultural History in the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of History and Technology. B>RIDGEPORT, , CONNECTICUT, was fast be speak of the Eastern glories of Iranistan, we have coming a center of industry by the middle of the and are to have in this vicinity, many dwelling- nineteenth century; carriages, leather goods, and houses worthy of particular notice as specimens of metal wares were among the products for which it architecture. -

Global Nomads: Techno and New Age As Transnational Countercultures

1111 2 Global Nomads 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 A uniquely ‘nomadic ethnography,’ Global Nomads is the first in-depth treat- 3111 ment of a counterculture flourishing in the global gulf stream of new electronic 4 and spiritual developments. D’Andrea’s is an insightful study of expressive indi- vidualism manifested in and through key cosmopolitan sites. This book is an 5 invaluable contribution to the anthropology/sociology of contemporary culture, 6 and presents required reading for students and scholars of new spiritualities, 7 techno-dance culture and globalization. 8 Graham St John, Research Fellow, 9 School of American Research, New Mexico 20111 1 D'Andrea breaks new ground in the scholarship on both globalization and the shaping of subjectivities. And he does so spectacularly, both through his focus 2 on neomadic cultures and a novel theorization. This is a deeply erudite book 3 and it is a lot of fun. 4 Saskia Sassen, Ralph Lewis Professor of Sociology 5 at the University of Chicago, and Centennial Visiting Professor 6 at the London School of Economics. 7 8 Global Nomads is a unique introduction to the globalization of countercultures, 9 a topic largely unknown in and outside academia. Anthony D’Andrea examines 30111 the social life of mobile expatriates who live within a global circuit of counter- 1 cultural practice in paradoxical paradises. 2 Based on nomadic fieldwork across Spain and India, the study analyzes how and why these post-metropolitan subjects reject the homeland to shape an alternative 3 lifestyle. They become artists, therapists, exotic traders and bohemian workers seek- 4 ing to integrate labor, mobility and spirituality within a cosmopolitan culture of 35 expressive individualism. -

Barnum Museum, Planning to Digitize the Collections

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the NEH Division of Preservation and Access application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/preservation/humanities-collections-and-reference- resources for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Preservation and Access staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Planning for "The Greatest Digitization Project on Earth" with the P. T. Barnum Collections of The Barnum Museum Foundation Institution: Barnum Museum Project Director: Adrienne Saint Pierre Grant Program: Humanities Collections and Reference Resources 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 411, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8570 F 202.606.8639 E [email protected] www.neh.gov The Barnum Museum Foundation, Inc. Application to the NEH/Humanities Collections and Reference Resources Program Narrative Significance Relevance of the Collections to the Humanities Phineas Taylor Barnum's impact reaches deep into our American heritage, and extends far beyond his well-known circus enterprise, which was essentially his “retirement project” begun at age sixty-one. -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

A Description of the Main Characters in the Movie the Greatest Showman

A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN A PAPER BY ELVA RAHMI REG.NO: 152202024 DIPLOMA III ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF CULTURE STUDY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH SUMATERA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I am ELVA RAHMI, declare that I am the sole author of this paper. Except where reference is made in the text of this paper, this paper contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a paper by which I have qualified for or awarded another degree. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of this paper. This paper has not been submitted for the award of another degree in any tertiary education. Signed : ……………. Date : 2018 i UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA COPYRIGHT DECLARATION Name: ELVA RAHMI Title of Paper: A DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE MOVIE THE GREATEST SHOWMAN. Qualification: D-III / Ahli Madya Study Program : English 1. I am willing that my paper should be available for reproduction at the discretion of the Libertarian of the Diploma III English Faculty of Culture Studies University of North Sumatera on the understanding that users are made aware of their obligation under law of the Republic of Indonesia. 2. I am not willing that my papers be made available for reproduction. Signed : ………….. Date : 2018 ii UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ABSTRACT The title of this paper is DESCRIPTION OF THE MAIN CHARACTERS IN THE GREATEST SHOWMAN MOVIE. The purpose of this paper is to find the main character. -

Symphony Shopping

Table of Contents | Week 1 7 bso news 15 on display in symphony hall 16 bso music director andris nelsons 18 the boston symphony orchestra 21 a message from andris nelsons 22 this week’s program Notes on the Program 24 The Program in Brief… 25 Dmitri Shostakovich 33 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky 41 Sergei Rachmaninoff 49 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artist 55 Evgeny Kissin 58 sponsors and donors 78 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 83 symphony hall information the friday preview talk on october 2 is given by bso director of program publications marc mandel. program copyright ©2015 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. program book design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photo of Andris Nelsons by Chris Lee cover design by BSO Marketing BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617)266-1492 bso.org andris nelsons, ray and maria stata music director bernard haitink, lacroix family fund conductor emeritus seiji ozawa, music director laureate 135th season, 2015–2016 trustees of the boston symphony orchestra, inc. William F. Achtmeyer, Chair • Paul Buttenwieser, President • George D. Behrakis, Vice-Chair • Cynthia Curme, Vice-Chair • Carmine A. Martignetti, Vice-Chair • Theresa M. Stone, Treasurer David Altshuler • Ronald G. Casty • Susan Bredhoff Cohen • Richard F. Connolly, Jr. • Alan J. Dworsky • Philip J. Edmundson, ex-officio • William R. Elfers • Thomas E. Faust, Jr. • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Susan Hockfield • Barbara W. Hostetter • Stephen B. Kay • Edmund Kelly • Martin Levine, ex-officio • Joyce Linde • John M. Loder • Nancy K. Lubin • Joshua A. Lutzker • Robert J. Mayer, M.D. -

“Big on Family”: the Representation of Freaks in Contemporary American Culture

Master’s Degree programme – Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004) in History of North-American Culture Final Thesis “Big on Family”: The Representation of Freaks in Contemporary American Culture Supervisor Ch. Prof. Simone Francescato Ch. Prof. Fiorenzo Iuliano University of Cagliari Graduand Luigi Tella Matriculation Number 846682 Academic Year 2014 / 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF ILLUSTRATIONS ............................................................................................. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER I: FREAKS IN AMERICA .............................................................................. 11 1.1 – The Notion of “Freak” and the Freak Show ........................................................... 11 1.1.1 – From the Monstrous Races to Bartholomew Fair ................................................. 14 1.1.2 – Freak Shows in the United States ......................................................................... 20 1.1.3 – The Exotic Mode and the Aggrandized Mode ...................................................... 28 1.2 – The Representation of Freaks in American Culture ............................................. 36 1.2.1 – Freaks in American Literature .............................................................................. 36 1.2.2 – Freaks on Screen ..................................................................................................