Article Under Her Eye: Digital Drag As Obfuscation and Countersurveillance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archiving Possibilities with the Victorian Freak Show a Dissertat

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE “Freaking” the Archive: Archiving Possibilities With the Victorian Freak Show A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ann McKenzie Garascia September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Joseph Childers, Co-Chairperson Dr. Susan Zieger, Co-Chairperson Dr. Robb Hernández Copyright by Ann McKenzie Garascia 2017 The Dissertation of Ann McKenzie Garascia is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation has received funding through University of California Riverside’s Dissertation Year Fellowship and the University of California’s Humanities Research Institute’s Dissertation Support Grant. Thank you to the following collections for use of their materials: the Wellcome Library (University College London), Special Collections and University Archives (University of California, Riverside), James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center (San Francisco Public Library), National Portrait Gallery (London), Houghton Library (Harvard College Library), Montana Historical Society, and Evanion Collection (the British Library.) Thank you to all the members of my dissertation committee for your willingness to work on a project that initially described itself “freakish.” Dr. Hernández, thanks for your energy and sharp critical eye—and for working with a Victorianist! Dr. Zieger, thanks for your keen intellect, unflappable demeanor, and ready support every step of the process. Not least, thanks to my chair, Dr. Childers, for always pushing me to think and write creatively; if it weren’t for you and your Dickens seminar, this dissertation probably wouldn’t exist. Lastly, thank you to Bartola and Maximo, Flora and Martinus, Lalloo and Lala, and Eugen for being demanding and lively subjects. -

Ghost Signs Are More Than Paintings on Brick

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2020 ghost signs are more than paintings on brick Eric Anthony Berdis Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons © Eric Anthony Berdis Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/6287 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©2020 All Rights Reserved ghost signs are more than paintings on brick A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University Eric Anthony Berdis B.F.A. Slippery Rock University, 2013 Post-baccalaureate Tyler School of Art, 2016 M.F.A. Virginia Commonwealth University, 2020 Director: Hillary Waters Fayle Assistant Professor- Fiber and Area Head of Fiber Craft/ Material Studies Department Jack Wax Professor - Glass and Area Head of Glass Craft/ Material Studies Department Kelcy Chase Folsom Assistant Professor - Clay Craft/ Material Studies Department Dr. Tracy Stonestreet Graduate Faculty Craft/ Material Studies Department v Acknowledgments Thank you to my amazing studio mate Laura Boban for welcoming me into your life, dreams, and being a shoulder of support as we walk on this journey together. You have taught me so much and your strength, thoughtfulness, and empathy make me both grateful and proud to be your peer. Thank you to Hillary Fayle for the encouragement, your critical feedback has been imperative to my growth. -

The Caffe Cino

DESIGNATION REPORT The Caffe Cino Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 DESIGNATION REPORT The Caffe Cino LOCATION Borough of Manhattan 31 Cornelia Street LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE No. 31 Cornelia Street in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan is culturally significant for its association with the Caffe Cino, which occupied the building’s ground floor commercial space from 1958 to 1968. During those ten years, the coffee shop served as an experimental theater venue, becoming the birthplace of Off-Off-Broadway and New York City’s first gay theater. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 Former location of the Caffe Cino, 31 Cornelia Street 2019 LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Lisa Kersavage, Executive Director Sarah Carroll, Chair Mark Silberman, Counsel Frederick Bland, Vice Chair Kate Lemos McHale, Director of Research Diana Chapin Cory Herrala, Director of Preservation Wellington Chen Michael Devonshire REPORT BY Michael Goldblum MaryNell Nolan-Wheatley, Research Department John Gustafsson Anne Holford-Smith Jeanne Lutfy EDITED BY Adi Shamir-Baron Kate Lemos McHale and Margaret Herman PHOTOGRAPHS BY LPC Staff Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission The Caffe Cino LP-2635 June 18, 2019 3 of 24 The Caffe Cino the National Parks Conservation Association, Village 31 Cornelia Street, Manhattan Preservation, Save Chelsea, and the Bowery Alliance of Neighbors, and 19 individuals. No one spoke in opposition to the proposed designation. The Commission also received 124 written submissions in favor of the proposed designation, including from Bronx Borough President Reuben Diaz, New York Designation List 513 City Council Member Adrienne Adams, the LP-2635 Preservation League of New York State, and 121 individuals. -

STOP AIDS Project Records, 1985-2011M1463

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8v125bx Online items available Guide to the STOP AIDS Project records, 1985-2011M1463 Laura Williams and Rebecca McNulty, October 2012 Department of Special Collections and University Archives October 2012; updated March 2019 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the STOP AIDS Project M1463 1 records, 1985-2011M1463 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: STOP AIDS Project records, creator: STOP AIDS Project Identifier/Call Number: M1463 Physical Description: 373.25 Linear Feet(443 manuscript boxes; 136 record storage boxes; 9 flat boxes; 3 card boxes; 21 map folders and 10 rolls) Date (inclusive): 1985-2011 Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36-48 hours in advance. For more information on paging collections, see the department's website: http://library.stanford.edu/depts/spc/spc.html. Abstract: Founded in 1984 (non-profit status attained, 1985), the STOP AIDS Project is a community-based organization dedicated to the prevention of HIV transmission among gay, bisexual and transgender men in San Francisco. Throughout its history, the STOP AIDS Project has been overwhelmingly successful in meeting its goal of reducing HIV transmission rates within the San Francisco Gay community through innovative outreach and education programs. The STOP AIDS Project has also served as a model for community-based HIV/AIDS education and support, both across the nation and around the world. The STOP AIDS Project records are comprised of behavioral risk assessment surveys; social marketing campaign materials, including HIV/AIDS prevention posters and flyers; community outreach and workshop materials; volunteer training materials; correspondence; grant proposals; fund development materials; administrative records; photographs; audio and video recordings; and computer files. -

Beyond the Gay Ghetto

chapter 1 Beyond the Gay Ghetto Founding Debates in Gay Liberation In October 1969, Gay Liberation Theater staged a street performance the group called “No Vietnamese Ever Called Me a Queer.” These activ- ists brought their claims to two distinct audiences: fellow students at the University of California, Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza and fellow gay men at a meeting of the San Francisco–based Society for Individual Rights (SIR). The student audience was anti-war but largely straight, while SIR backed gay inclusion in the military and exemplified the moderate center of the “homophile” movement—“homophile” being the name for an existing and older network of gay and lesbian activism. Gay Liberation Theater adapted Muhammad Ali’s statement when refusing the draft that “no Viet Cong ever called me nigger” and, through this, indicted a society that demanded men kill rather than desire one another. They opposed the Vietnam War and spoke to the self-interest of gay men by declaring: “We’re not going to fight in an army that discriminates against us. Nor are we going to fight for a country that will not hire us and fires us. We are going to fight for ourselves and our lovers in places like Berkeley where the Berkeley police last April murdered homosexual brother Frank Bartley (never heard of him?) while cruising in Aquatic Park.” Frank Bartley was a thirty-three-year-old white man who had recently been killed by a plainclothes officer who claimed that Bartley “resisted arrest” and “reached for his groin.”1 In highlighting Bartley’s case, Gay Liberation Theater pushed back against the demands of assim- ilation and respectability and linked opposition to the Vietnam War with 17 Hobson - Lavender and Red.indd 17 29/06/16 4:30 PM 18 | Beyond the Gay Ghetto support for sexual expression. -

Transgender History / by Susan Stryker

u.s. $12.95 gay/Lesbian studies Craving a smart and Comprehensive approaCh to transgender history historiCaL and Current topiCs in feminism? SEAL Studies Seal Studies helps you hone your analytical skills, susan stryker get informed, and have fun while you’re at it! transgender history HERE’S WHAT YOU’LL GET: • COVERAGE OF THE TOPIC IN ENGAGING AND AccESSIBLE LANGUAGE • PhOTOS, ILLUSTRATIONS, AND SIDEBARS • READERS’ gUIDES THAT PROMOTE CRITICAL ANALYSIS • EXTENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHIES TO POINT YOU TO ADDITIONAL RESOURCES Transgender History covers American transgender history from the mid-twentieth century to today. From the transsexual and transvestite communities in the years following World War II to trans radicalism and social change in the ’60s and ’70s to the gender issues witnessed throughout the ’90s and ’00s, this introductory text will give you a foundation for understanding the developments, changes, strides, and setbacks of trans studies and the trans community in the United States. “A lively introduction to transgender history and activism in the U.S. Highly readable and highly recommended.” SUSAN —joanne meyerowitz, professor of history and american studies, yale University, and author of How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality In The United States “A powerful combination of lucid prose and theoretical sophistication . Readers STRYKER who have no or little knowledge of transgender issues will come away with the foundation they need, while those already in the field will find much to think about.” —paisley cUrrah, political -

Tracing the History of Trans and Gender Variant Filmmakers

Laura Horak Tracing the History of Trans and Gender Variant Filmmakers Abstract Most writing on transgender cinema focuses on representations of trans people, rather than works made by trans people. This article surveys the history of trans and gender variant people creating audiovisual media from the beginning of cinema through today. From the professional gender impersonators of the stage who crossed into film during the medium’s first decades to self- identified transvestite and transsexual filmmakers, like Ed Wood and Christine Jorgensen of the mid-twentieth century, to the enormous upsurge in trans filmmaking of the 1990s, this article explores the rich and complex history of trans and gender variant filmmaking. It also considers the untraceable gender variant filmmakers who worked in film and television without their gender history becoming known and those who made home movies that have been lost to history. “They cannot represent themselves, they must Keegan have importantly analyzed the work of be represented.”1 Viviane Namaste begins her particular trans and gender variant filmmakers, foundational essay on transsexual access to the focusing primarily on the 1990s and 2000s.7 More media with this quote from Karl Marx. Namaste recently, Keegan and others have investigated trans described the many obstacles to transsexual self- experiences of spectatorship and articulated a representation in the 1990s and early 2000s. Since concept of “trans aesthetics” that exceeds identity then, new technologies have enabled hundreds categories.8 Trans filmmakers have also begun to of thousands of trans people to create and theorize their own and others’ work.9 Scholars have circulate amateur videos on YouTube.2 However, also investigated trans multimedia production, in representations of trans people made by and the form of zines, Tumblr blogs, photography, and for cisgender people still dominate mainstream interactive digital media.10 However, there has not media. -

News Censorship Dateline

NEWS CENSORSHIP DATELINE LIBRARIES In his October video, Dorr reads To fight back against the self- Coeur D’Alene, Idaho a blog post titled “May God and the anointed censor, the library is display- Books that a patron judged to be crit- Homosexuals of OC Pride Please For- ing the recently found missing movies ical of President Donald Trump disap- give Us!” from his website, which he with a sign that reads: “The Berkley peared from the shelves of the Coeur calls “Rescue The Perishing.” The Public Library is against censorship. d’Alene Public Library. video ends with Dorr burning Two Someone didn’t want you to check Librarian Bette Ammon fished this Boys Kissing, a young adult novel by these items out. They deliberately hid complaint from the suggestion box: David Levithan; Morris Micklewhite all of these items so you wouldn’t find “I noticed a large volume of books and the Tangerine Dress, a children’s them. This is not how libraries work.” attacking our president. And I am book about a boy who likes to wear a Arnsman said the most recent Fifty going to continue hiding these books tangerine dress, by Christine Balda- Shades movie, Fifty Shades Freed, was in the most obscure places I can find cchino; This Day In June, a picture noticed missing in mid-June. A year to keep this propaganda out of the book about a pride parade, by Gayle ago, she said, the second of three Fifty hands of young minds. Your liberal E. Pitman, and Families, Families, Fam- Shades movies, Fifty Shades Darker, angst gives me great pleasure.” ilies! by Suzanne and Max Lang, about also went mysteriously missing. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar, ITVS 415

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar, ITVS 415-356-8383 x 244 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] For downloadable images, visit http://pressroom.pbs.org WE WERE HERE, A HEART-WRENCHING LOOK AT THE EARLY DAYS OF THE AIDS CRISIS IN SAN FRANCISCO AS TOLD BY THE SURVIVORS, PREMIERES ON INDEPENDENT LENS ON THURSDAY, JUNE 14, 2012 “Of all the cinematic explorations of the AIDS crisis, not one is more heartbreaking and inspiring than We Were Here. The humility, wisdom and cumulative sorrow expressed lend the film a glow of spirituality and infuse it with grace. One of the top ten films of the year.” -- Stephen Holden, The New York Times “It’s impossible for a single film to capture the devastation wrought by AIDS, or the heroism with which many in the LGBT community responded to it. But director David Weissman’s documentary is such a powerful achievement because he just about does it.” -- Ernest Hardy, LA Weekly (San Francisco, CA) — Both inspiring and devastating, David Weissman’s We Were Here revisits the arrival in San Francisco of what was called the “Gay Plague” in the early 1980s. It illuminates the profound personal and community issues raised by the AIDS epidemic as well as the broad political and social upheavals it unleashed. It offers a cathartic validation for the generation that suffered through, and responded to, the onset of AIDS while opening a window of understanding to those who have only the vaguest notions of what transpired in those years. -

Lgbtq Abyss Zignego Ready Mix, Inc

Democratic Socialists of America: Communism for the New Millennium • The Racist American Flag? August 5 , 2019 • $3.95 www.TheNewAmerican.com THAT FREEDOM SHALL NOT PERISH “DRAG”ING KIDS INTO THE LGBTQ ABYSS ZIGNEGO READY MIX, INC. W226 N2940 DUPLAINVILLE ROAD WAUKESHA, WI 53186 262-542-0333 • www.Zignego.com RESCUING OUR CHILDREN SUMMER TOUR 2019 WITH ALEX NEWMAN There is a reason the Deep State globalists sound so confident about the success of their agenda — they have a secret weapon: More than 85 percent of American children are being indoctrinated by radicalized government schools. In this explosive talk, Alex Newman exposes the insanity that has taken over the public school system. From the sexualization of children and the reshaping of values to deliberate dumbing down, Alex shows how dangerous this threat is — not just to our children, but also to the future of faith, family, and freedom — and what every American can do about it. VIRGINIA OREGON ✔ May 27 / Hampton / Tricia Stall / 757-897-4842 ✔ July 10 / King City / Sally Crino / 503-522-3926 ✔ May 29 / Chesapeake / Tricia Stall / 757-897-4842 WASHINGTON ✔ May 30 / Richmond / Thomas Redfern / 804-722-1084 ✔ July 12 & 13 / Spokane / Caleb Collier / 509-999-0479 ✔ June 4 / Falls Church / Tricia Stall / 757-897-4842 ✔ July 14 / Lynnwood (Seattle) / Lillian Erickson / 425-269-9991 CONNECTICUT CALIFORNIA ✔ June 7 / Hartford / Imani Mamalution / 860-983-5279 ✔ July 18 / Lodi / Greg Goehring / 209-712-1635 ✔ June 8 / Hartford / Imani Mamalution / 860-983-5279 ✔ July 23 / Thousand Oaks -

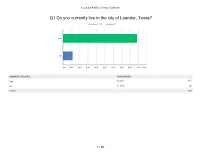

Leander Public Library Feedback Survey

Leander Public Library feedback Q1 Do you currently live in the city of Leander, Texas? Answered: 740 Skipped: 1 Yes No 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% ANSWER CHOICES RESPONSES Yes 88.38% 654 No 11.62% 86 TOTAL 740 1 / 97 Leander Public Library feedback Q2 How often do you or your family members visit Leander Public Library? Answered: 740 Skipped: 1 Every day A few times a week About once a week A few times a month Once a month Less than once a month 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% ANSWER CHOICES RESPONSES Every day 0.95% 7 A few times a week 9.19% 68 About once a week 12.43% 92 A few times a month 25.41% 188 Once a month 18.38% 136 Less than once a month 33.65% 249 TOTAL 740 2 / 97 Leander Public Library feedback Q3 How many times have you or your family members checked out a library book? Answered: 738 Skipped: 3 Every day A few times a week About once a week A few times a month Once a month Less than once a month 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% ANSWER CHOICES RESPONSES Every day 0.54% 4 A few times a week 4.47% 33 About once a week 11.11% 82 A few times a month 22.90% 169 Once a month 16.94% 125 Less than once a month 44.04% 325 TOTAL 738 3 / 97 Leander Public Library feedback Q4 Please select any library events you or your family members have attended at Leander Public Library in the past: Answered: 602 Skipped: 139 Baby & Me LEGO Lab Gaming for Grown-Ups Adult Book Club Teen Anime Club Dinner and a Movie Leander Writers' Guild A Universe of Stories Frogs, Scales, & Puppy Dog.. -

Drag Queen Storytimes

NEWS DRAG QUEEN STORYTIMES EDITOR’S NOTE: An increasing By the end of the event, three Jacksonville, Florida number of challenges to free expression more protesters showed up, includ- “Storybook Pride Prom” at Willow- focus on “drag queen storytimes,” where ing frequent Vallejo Times-Herald branch Library in Riverside, sched- the target is usually not the titles, con- letter-to-the-editor writer Ryan uled for Friday, June 28, 2019, was tents, nor authors of any specific books, but Messano, who often rails against cancelled on Monday, June 24, after rather who is reading them. In this version homosexuals and other issues he the library had received hundreds of of storytimes where picture books are read believes are leading the country down phone calls supporting and protesting aloud to children, performers dressed in a negative path. the event. drag (usually men dressed in theatrically One of the counter-protesters was In a switch from a typical drag feminine costumes) try to encourage both a Michael Wilson of Vallejo, aide to queen storytime, in which an adult love of reading and acceptance of diver- Solano County Supervisor Erin Han- dressed in drag reads to young chil- sity. Some of the performers and events are nigan and the city’s second openly gay dren, the Storybook Prom planned affiliated with Drag Queen Story Hour, a Councilman in the early 2000s. to give the hundred teenagers who network of local organizations that began “I’m an advocate of Pride Month signed up a chance to dress as their in San Francisco; others are independent.