Rabble Rousers Merry Pranksters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archiving Possibilities with the Victorian Freak Show a Dissertat

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE “Freaking” the Archive: Archiving Possibilities With the Victorian Freak Show A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ann McKenzie Garascia September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Joseph Childers, Co-Chairperson Dr. Susan Zieger, Co-Chairperson Dr. Robb Hernández Copyright by Ann McKenzie Garascia 2017 The Dissertation of Ann McKenzie Garascia is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation has received funding through University of California Riverside’s Dissertation Year Fellowship and the University of California’s Humanities Research Institute’s Dissertation Support Grant. Thank you to the following collections for use of their materials: the Wellcome Library (University College London), Special Collections and University Archives (University of California, Riverside), James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center (San Francisco Public Library), National Portrait Gallery (London), Houghton Library (Harvard College Library), Montana Historical Society, and Evanion Collection (the British Library.) Thank you to all the members of my dissertation committee for your willingness to work on a project that initially described itself “freakish.” Dr. Hernández, thanks for your energy and sharp critical eye—and for working with a Victorianist! Dr. Zieger, thanks for your keen intellect, unflappable demeanor, and ready support every step of the process. Not least, thanks to my chair, Dr. Childers, for always pushing me to think and write creatively; if it weren’t for you and your Dickens seminar, this dissertation probably wouldn’t exist. Lastly, thank you to Bartola and Maximo, Flora and Martinus, Lalloo and Lala, and Eugen for being demanding and lively subjects. -

Pandoras Box CD-List 06-2006 Short

Pandoras Box CD-list 06-2006 short.xls Form ARTIST TITLE year No Label price CD 2066 & THEN Reflections !! 1971 SB 025 Second Battle 15,00 € CD 3 HUEREL 3 HUEREL 1970-75 WPC6 8462 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3 HUEREL Huerel Arisivi 1970-75 WPC6 8463 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3SPEED AUTOMATIC no man's land 2004 SA 333 Nasoni 15,00 € CD 49 th PARALLELL 49 th PARALLELL 1969 Flashback 008 Flashback 11,90 € CD 49TH PARALLEL 49TH PARALLEL 1969 PACELN 48 Lion / Pacemaker 17,90 € CD 50 FOOT HOSE Cauldron 1968 RRCD 141 Radioactive 14,90 € CD 7 th TEMPLE Under the burning sun 1978 RRCD 084 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A - AUSTR Music from holy Ground 1970 KSG 014 Kissing Spell 19,95 € CD A BREATH OF FRESH AIR A BREATH OF FRESH AIR 196 RRCD 076 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A CID SYMPHONY FISCHBACH AND EWING - (21966CD) -67 GF-135 Gear Fab 14,90 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER A Foot in coldwater 1972 AGEK-2158 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER All around us 1973 AGEK-2160 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 1 1973 BEBBD 25 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 2 1973 BEBBD 26 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER The second foot in coldwater 1973 AGEK-2159 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - (2CD) 1972-73 AGEK2-2161 Unidisc 17,90 € CD A JOINT EFFORT FINAL EFFORT 1968 RRCD 153 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy 1968 FB 11 Flashback 15,00 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy - (Digip.) 1968 PACE-034 Pacemaker 15,90 € CD AARDVARK Aardvark 1970 SRMC 0056 Si-Wan 19,95 € CD AARDVARK AARDVARK - (lim. -

Discoursing Finnish Rock. Articulations of Identities in the Saimaa-Ilmiö Rock Documentary Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2010, 229 P

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 140 Terhi Skaniakos Discoursing Finnish Rock Articulations of Identities in the Saimaa-ilmiö Rock Documentary JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 140 Terhi Skaniakos Discoursing Finnish Rock Articulations of Identities in the Saimaa-ilmiö Rock Documentary Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston vanhassa juhlasalissa S210 toukokuun 14. päivänä 2010 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in Auditorium S210, on May 14, 2010 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2010 Discoursing Finnish Rock Articulations of Identities in the Saimaa-ilmiö Rock Documentary JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 140 Terhi Skaniakos Discoursing Finnish Rock Articulations of Identities in the Saimaa-ilmiö Rock Documentary UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2010 Editor Erkki Vainikkala Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Pekka Olsbo Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Paula Kalaja, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Tarja Nikula, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä Cover picture by Marika Tamminen, Museum Centre Vapriikki collections URN:ISBN:978-951-39-3887-1 ISBN 978-951-39-3887-1 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-3877-2 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright © 2010 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2010 ABSTRACT Skaniakos, Terhi Discoursing Finnish Rock. -

Global Nomads: Techno and New Age As Transnational Countercultures

1111 2 Global Nomads 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 A uniquely ‘nomadic ethnography,’ Global Nomads is the first in-depth treat- 3111 ment of a counterculture flourishing in the global gulf stream of new electronic 4 and spiritual developments. D’Andrea’s is an insightful study of expressive indi- vidualism manifested in and through key cosmopolitan sites. This book is an 5 invaluable contribution to the anthropology/sociology of contemporary culture, 6 and presents required reading for students and scholars of new spiritualities, 7 techno-dance culture and globalization. 8 Graham St John, Research Fellow, 9 School of American Research, New Mexico 20111 1 D'Andrea breaks new ground in the scholarship on both globalization and the shaping of subjectivities. And he does so spectacularly, both through his focus 2 on neomadic cultures and a novel theorization. This is a deeply erudite book 3 and it is a lot of fun. 4 Saskia Sassen, Ralph Lewis Professor of Sociology 5 at the University of Chicago, and Centennial Visiting Professor 6 at the London School of Economics. 7 8 Global Nomads is a unique introduction to the globalization of countercultures, 9 a topic largely unknown in and outside academia. Anthony D’Andrea examines 30111 the social life of mobile expatriates who live within a global circuit of counter- 1 cultural practice in paradoxical paradises. 2 Based on nomadic fieldwork across Spain and India, the study analyzes how and why these post-metropolitan subjects reject the homeland to shape an alternative 3 lifestyle. They become artists, therapists, exotic traders and bohemian workers seek- 4 ing to integrate labor, mobility and spirituality within a cosmopolitan culture of 35 expressive individualism. -

OZ 35 Richard Neville Editor

University of Wollongong Research Online OZ magazine, London Historical & Cultural Collections 5-1971 OZ 35 Richard Neville Editor Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/ozlondon Recommended Citation Neville, Richard, (1971), OZ 35, OZ Publications Ink Limited, London, 48p. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ozlondon/35 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] OZ 35 Description This issue appears with the help o f Jim Anderson, Pat Bell, Stanislav Demidjuk, Felix Dennis, Simon Kentish, Debbie Knight, Stephen Litster, Brian McCracken, Mike Murphy, Richard Neville, John O’Neil, Chris Rowley, George Snow, David Wills. Thanks for artwork, photographs and valuable help to Eddie Belchamber, Andy Dudzinski, Rod Beddatl, Rip-Off rP ess, David Nutter, Mike Weller, Dan Pearce, Colin Thomas, Charles Shaar Murray, Sue Miles and those innumerable people who write us letters, which we are unable to print and sometimes forget to reply to. Contents: Special Pig issue cover by Ed Belchamber. Stop Press: OZ Obscenity Trial June 22nd Old Bailey. ‘The onC tortions of Modern Cricket’ A commentary on the current state of the game – Suck, sexuality and politics by Jim Haynes + graphics. ‘The onC tinuing Story of Lee Heater’ by Jim Anderson + graphics. How Howie Made it in the Real World 3p cartoon by Gore. Full page Keef Hartley Band ad. ‘The Bob Sleigh Case’ by Stanislav Demidjuk – freak injustice. ‘Act Like a Lady’ – gay advice from Gay Dealer + graphics by Rod Beddall. Chart: ‘The eM dical Effects of Mind-Altering Substances’ – based on charts by Sidney Cohen MD and Joel Fort MD. -

American Square Dance Vol. 44, No. 4

AMERICAN SQUARE DANCE Annual $12 APRIL 1989 Single $1.25 HANHURST'S TAPE & RECORD SERVICE THE "ORIGINAL" z SUBSCRIPTION z dS3 cc L TAPE SERVICE a Have you heard all the 75-80 releases that Y 1VdVH3 TR 1: 1 have come out in the 1: OUN 1V last 3 months? C Since 1971 GO OH CHICA 1VA "I think you and your staff are doing a great I— job with the record service. You have pro- vided very responsive service when it comes )IOONIHO to record ordering. Having both the tape and record service you provide, is well worth the 33 expense." -- S.H., APO, New York Er cr —4 a. ❑ 1 1: "l am quite impressed with the quality of the reproduction of the monthly Hanhurst tape." B.B., Alberta, Canada cc 009 03 1 SE HOU 139 0 The Continuing Choice of 1,300 Callers! 0 CH CALL TOLL FREE NOW RAN t - FOR FREE SAMPLE TAPE VISA' UV9 - 1-800-445-7398 9 (In N.J. 201-445-7398) HANHURST'S TAPE & RECORD SERVICE STAR P.O. BOX 687 z RIDGEWOOD, N.J. 07451-0687 —1 BLUE EUREKA STING SNOW LOU MAC BIG MAC AMERICAN [--71 SaURRE ORNCE VOLUME 44, No. 4 THE INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE APRIL 1989 WITH THE SWINGING LINES ASD FEATURES FOR ALL OUR READERS SPEAK 4 Co-Editorial 6 Grand Zip 5 bly-Line 41 Straight Talk 7 Meandering with Stan 43 Feedback 11 Get Out Of Step 13 April Fool Fun SQUARE DANCE SCENE 14 Dancing Daffy-nitions 20 Late Callerlab News 15 The Anaria Sheikdom 58 A/C Lines (Advanced & Challenge) 19 The Late Great Square Dance 70 Callerlab News 21 Name A Day—Or A Club 72 International News 23 Vacation '89 (Events) 93 S/D Mastercard 29 Encore 101 LSF Institute 31 Hem-Line 104 Run To Oklahoma 35 Dandy Idea 36 Product Line ROUNDS 37 Best Club Trick 33 Cue Tips 39 On Line 63 R/D Pulse Poll 45 Party Line 47 Dancing Tips 79 Facing the L.O.D. -

The Clash and Mass Media Messages from the Only Band That Matters

THE CLASH AND MASS MEDIA MESSAGES FROM THE ONLY BAND THAT MATTERS Sean Xavier Ahern A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill © 2012 Sean Xavier Ahern All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis analyzes the music of the British punk rock band The Clash through the use of media imagery in popular music in an effort to inform listeners of contemporary news items. I propose to look at the punk rock band The Clash not solely as a first wave English punk rock band but rather as a “news-giving” group as presented during their interview on the Tom Snyder show in 1981. I argue that the band’s use of communication metaphors and imagery in their songs and album art helped to communicate with their audience in a way that their contemporaries were unable to. Broken down into four chapters, I look at each of the major releases by the band in chronological order as they progressed from a London punk band to a globally known popular rock act. Viewing The Clash as a “news giving” punk rock band that inundated their lyrics, music videos and live performances with communication images, The Clash used their position as a popular act to inform their audience, asking them to question their surroundings and “know your rights.” iv For Pat and Zach Ahern Go Easy, Step Lightly, Stay Free. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the help of many, many people. -

BLOOD, SWEAT Union Snubs Musicians the MUSICIANS UNION Hasrefused Toreply to Last Week'sarticle in Recordmirrorin Which C TEARS U.K

TEENAGE Andy Fairweather recordCINEMA-page9 Lowe Group-page5 mirror MAY 16, 1970. BLOOD, SWEAT Union snubs musicians THE MUSICIANS UNION hasrefused toreply to last week'sarticle in RecordMirrorin which C TEARS U.K. MEG some musicians criticised the union. Instead a union spokesman said: "We will not be able to have any comments available as there is an executive committeemeetingthis week and that is far more importantthanthe HIE statements madeby people in this article. BLOOD, SWEAT AND TEARS are DEFINITELY "We cannot say when coming to Europe for their first ever tour! They are ourcommentwill be being brought over exclusively by Radio Luxembourg ready." In effect the union is who hold all interview and performance rights for the snubbingits members by group. saying that it has no time '208' programme to answer those who are director Tony Macarthur by critical of it, even though told RM: "The two the dossier of discontent Britishconcertswillbe Rodney was given to the union presentedinconjunction Collins ONE WEEK before it was with a major London published. promoter on the 24th 25thEnglish service during the In the article a number September. Together withgroup's two week stay in of allegations were made against the MU by pop CBS Records we are Europe. They willplay planning a giant reception musicians.And it has dates in Germany, France, since become the major for the group." Holland and Belgium in talkingpointof the Highlights of the additionto the industry during the week. concerts will be broadcast London concerts.Blood Record Mirror believes over Radio Luxembourg'sSweat and Tears will not thatitisimportant that appear anywhere in pop musiciansshould Europe before they fly in have a platform toair for'208',thestation's their views aboutthe Rolling firstpromotionofthis union, since it appears to kind in 37 years. -

Chapter 1. When Is Music Political?

Durham E-Theses Music, Civil Rights, and Counterculture: Critical Aesthetics and Resistance in the United States, 1957-1968 BARKER, THOMAS,PATRICK How to cite: BARKER, THOMAS,PATRICK (2016) Music, Civil Rights, and Counterculture: Critical Aesthetics and Resistance in the United States, 1957-1968, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11693/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Music, Civil Rights, and Counterculture: Critical Aesthetics and Resistance in the United States, 1957-1968 Thomas Barker PhD Music Department University of Durham 2016 Music, Civil Rights, and Counterculture: Critical Aesthetics and Resistance in the United States, 1957-1968 Thomas Barker Abstract This dissertation explores the role of music within the politics of liberation in the United States in the period of the late 1950s and the 1960s. Its focus is on the two dominant, but very different (and, it is argued, interconnected) mass political and cultural movements that converged in the course of the 1960s: civil rights and counterculture. -

Issue 171.Pmd

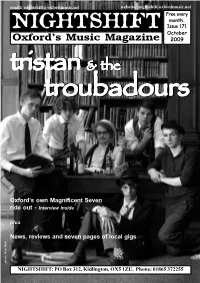

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 171 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2009 tristantristantristantristan &&& thethethe troubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadours Oxford’s own Magnificent Seven ride out - Interview inside plus News, reviews and seven pages of local gigs photo: Marc West photo: Marc NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net THIS MONTH’S OX4 FESTIVAL will feature a special Music Unconvention alongside its other attractions. The mini-convention, featuring a panel of local music people, will discuss, amongst other musical topics, the idea of keeping things local. OX4 takes place on Saturday 10th October at venues the length of Cowley Road, including the 02 Academy, the Bullingdon, East Oxford Community Centre, Baby Simple, Trees Lounge, Café Tarifa, Café Milano, the Brickworks and the Restore Garden Café. The all-day event has SWERVEDRIVER play their first Oxford gig in over a decade next been organised by Truck and local gig promoters You! Me! Dancing! Bands month. The one-time Oxford favourites, who relocated to London in the th already confirmed include hotly-tipped electro-pop outfit The Big Pink, early-90s, play at the O2 Academy on Thursday 26 November. The improvisational hardcore collective Action Beat and experimental hip hop band, who signed to Creation Records shortly after Ride in 1990, split in outfit Dälek, plus a host of local acts. Catweazle Club and the Oxford Folk 1999 but reformed in 2008, still fronted by Adam Franklin and Jimmy Festival will also be hosting acoustic music sessions. -

BB-1971-12-25-II-Tal

0000000000000000000000000000 000000.00W M0( 4'' .................111111111111 .............1111111111 0 0 o 041111%.* I I www.americanradiohistory.com TOP Cartridge TV ifape FCC Extends Radiation Cartridges Limits Discussion Time (Based on Best Selling LP's) By MILDRED HALL Eke Last Week Week Title, Artist, Label (Dgllcater) (a-Tr. B Cassette Nos.) WASHINGTON-More requests for extension of because some of the home video tuners will utilize time to comment on the government's rulemaking on unused TV channels, and CATV people fear conflict 1 1 THERE'S A RIOT GOIN' ON cartridge tv radiation limits may bring another two- with their own increasing channel capacities, from 12 Sly & the Family Stone, Epic (EA 30986; ET 30986) month delay in comment deadline. Also, the Federal to 20 and more. 2 2 LED ZEPPELIN Communications Commission is considering a spin- Cable TV says the situation is "further complicated Atlantic (Ampex M87208; MS57208) off of the radiated -signal CTV devices for separate by the fact that there is a direct connection to the 3 8 MUSIC consideration. subscriber's TV set from the cable system to other Carole King, Ode (MM) (8T 77013; CS 77013) In response to a request by Dell-Star Corp., which subscribers." Any interference factor would be mul- 4 4 TEASER & THE FIRECAT roposes a "wireless" or "radiated signal" type system, tiplied over a whole network of CATV homes wired Cat Stevens, ABM (8T 4313; CS 4313) the FCC granted an extension to Dec. 17 for com- to a master antenna. was 5 5 AT CARNEGIE HALL ments, and to Dec. -

Guilt, Forgiveness, and Reconciliation in Contemporary Music

IS SORRY REALLY THE HARDEST WORD? GUILT, FORGIVENESS, AND RECONCILIATION IN CONTEMPORARY MUSIC Ariana Sarah Phillips-Hutton Darwin College Department of Music University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 ABSTRACT IS SORRY REALLY THE HARDEST WORD? GUILT, FORGIVENESS, AND RECONCILIATION IN CONTEMPORARY MUSIC Ariana S. Phillips-Hutton Guilt, forgiveness, and reconciliation are fundamental themes in human musical life, and this thesis investigates how people articulate these experiences through musical performance in contemporary genres. I argue that by participating in performances, individuals enact social narratives that create and reinforce wider ideals of music’s roles in society. I assess the interpenetrations of music and guilt, forgiveness, and reconciliation through a number of case studies spanning different genres preceded by a brief introduction to my methodology. My analysis of Arnold Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw illustrates the themes (guilt, confession and memorialisation) and approach I adopt in the three main case studies. My examination of William Fitzsimmons’s indie folk album The Sparrow and the Crow, investigates how ideals of authenticity, self-revelation, and persona structure our understanding of the relationship between performer and audience in confessional indie music. Analyses of two contemporary choral settings of Psalm 51 by Arvo Pärt and James MacMillan examine the confessional relationship between human beings and God. I suggest that by