Freak Scene? Narrative, Audience & Scene Crawford, G and Gosling, VK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archiving Possibilities with the Victorian Freak Show a Dissertat

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE “Freaking” the Archive: Archiving Possibilities With the Victorian Freak Show A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ann McKenzie Garascia September 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Joseph Childers, Co-Chairperson Dr. Susan Zieger, Co-Chairperson Dr. Robb Hernández Copyright by Ann McKenzie Garascia 2017 The Dissertation of Ann McKenzie Garascia is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation has received funding through University of California Riverside’s Dissertation Year Fellowship and the University of California’s Humanities Research Institute’s Dissertation Support Grant. Thank you to the following collections for use of their materials: the Wellcome Library (University College London), Special Collections and University Archives (University of California, Riverside), James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center (San Francisco Public Library), National Portrait Gallery (London), Houghton Library (Harvard College Library), Montana Historical Society, and Evanion Collection (the British Library.) Thank you to all the members of my dissertation committee for your willingness to work on a project that initially described itself “freakish.” Dr. Hernández, thanks for your energy and sharp critical eye—and for working with a Victorianist! Dr. Zieger, thanks for your keen intellect, unflappable demeanor, and ready support every step of the process. Not least, thanks to my chair, Dr. Childers, for always pushing me to think and write creatively; if it weren’t for you and your Dickens seminar, this dissertation probably wouldn’t exist. Lastly, thank you to Bartola and Maximo, Flora and Martinus, Lalloo and Lala, and Eugen for being demanding and lively subjects. -

Pandoras Box CD-List 06-2006 Short

Pandoras Box CD-list 06-2006 short.xls Form ARTIST TITLE year No Label price CD 2066 & THEN Reflections !! 1971 SB 025 Second Battle 15,00 € CD 3 HUEREL 3 HUEREL 1970-75 WPC6 8462 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3 HUEREL Huerel Arisivi 1970-75 WPC6 8463 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3SPEED AUTOMATIC no man's land 2004 SA 333 Nasoni 15,00 € CD 49 th PARALLELL 49 th PARALLELL 1969 Flashback 008 Flashback 11,90 € CD 49TH PARALLEL 49TH PARALLEL 1969 PACELN 48 Lion / Pacemaker 17,90 € CD 50 FOOT HOSE Cauldron 1968 RRCD 141 Radioactive 14,90 € CD 7 th TEMPLE Under the burning sun 1978 RRCD 084 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A - AUSTR Music from holy Ground 1970 KSG 014 Kissing Spell 19,95 € CD A BREATH OF FRESH AIR A BREATH OF FRESH AIR 196 RRCD 076 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A CID SYMPHONY FISCHBACH AND EWING - (21966CD) -67 GF-135 Gear Fab 14,90 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER A Foot in coldwater 1972 AGEK-2158 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER All around us 1973 AGEK-2160 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 1 1973 BEBBD 25 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 2 1973 BEBBD 26 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER The second foot in coldwater 1973 AGEK-2159 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - (2CD) 1972-73 AGEK2-2161 Unidisc 17,90 € CD A JOINT EFFORT FINAL EFFORT 1968 RRCD 153 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy 1968 FB 11 Flashback 15,00 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy - (Digip.) 1968 PACE-034 Pacemaker 15,90 € CD AARDVARK Aardvark 1970 SRMC 0056 Si-Wan 19,95 € CD AARDVARK AARDVARK - (lim. -

Global Nomads: Techno and New Age As Transnational Countercultures

1111 2 Global Nomads 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 A uniquely ‘nomadic ethnography,’ Global Nomads is the first in-depth treat- 3111 ment of a counterculture flourishing in the global gulf stream of new electronic 4 and spiritual developments. D’Andrea’s is an insightful study of expressive indi- vidualism manifested in and through key cosmopolitan sites. This book is an 5 invaluable contribution to the anthropology/sociology of contemporary culture, 6 and presents required reading for students and scholars of new spiritualities, 7 techno-dance culture and globalization. 8 Graham St John, Research Fellow, 9 School of American Research, New Mexico 20111 1 D'Andrea breaks new ground in the scholarship on both globalization and the shaping of subjectivities. And he does so spectacularly, both through his focus 2 on neomadic cultures and a novel theorization. This is a deeply erudite book 3 and it is a lot of fun. 4 Saskia Sassen, Ralph Lewis Professor of Sociology 5 at the University of Chicago, and Centennial Visiting Professor 6 at the London School of Economics. 7 8 Global Nomads is a unique introduction to the globalization of countercultures, 9 a topic largely unknown in and outside academia. Anthony D’Andrea examines 30111 the social life of mobile expatriates who live within a global circuit of counter- 1 cultural practice in paradoxical paradises. 2 Based on nomadic fieldwork across Spain and India, the study analyzes how and why these post-metropolitan subjects reject the homeland to shape an alternative 3 lifestyle. They become artists, therapists, exotic traders and bohemian workers seek- 4 ing to integrate labor, mobility and spirituality within a cosmopolitan culture of 35 expressive individualism. -

OZ 35 Richard Neville Editor

University of Wollongong Research Online OZ magazine, London Historical & Cultural Collections 5-1971 OZ 35 Richard Neville Editor Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/ozlondon Recommended Citation Neville, Richard, (1971), OZ 35, OZ Publications Ink Limited, London, 48p. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ozlondon/35 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] OZ 35 Description This issue appears with the help o f Jim Anderson, Pat Bell, Stanislav Demidjuk, Felix Dennis, Simon Kentish, Debbie Knight, Stephen Litster, Brian McCracken, Mike Murphy, Richard Neville, John O’Neil, Chris Rowley, George Snow, David Wills. Thanks for artwork, photographs and valuable help to Eddie Belchamber, Andy Dudzinski, Rod Beddatl, Rip-Off rP ess, David Nutter, Mike Weller, Dan Pearce, Colin Thomas, Charles Shaar Murray, Sue Miles and those innumerable people who write us letters, which we are unable to print and sometimes forget to reply to. Contents: Special Pig issue cover by Ed Belchamber. Stop Press: OZ Obscenity Trial June 22nd Old Bailey. ‘The onC tortions of Modern Cricket’ A commentary on the current state of the game – Suck, sexuality and politics by Jim Haynes + graphics. ‘The onC tinuing Story of Lee Heater’ by Jim Anderson + graphics. How Howie Made it in the Real World 3p cartoon by Gore. Full page Keef Hartley Band ad. ‘The Bob Sleigh Case’ by Stanislav Demidjuk – freak injustice. ‘Act Like a Lady’ – gay advice from Gay Dealer + graphics by Rod Beddall. Chart: ‘The eM dical Effects of Mind-Altering Substances’ – based on charts by Sidney Cohen MD and Joel Fort MD. -

Rabble Rousers Merry Pranksters

Rabble Rousers and Merry Pranksters A History of Anarchism in Aotearoa/New Zealand From the Mid-1950s to the Early 1980s Toby Boraman Katipo Books and Irrecuperable Press Published by Katipo Books and Irrecuperable Press 2008 Second Edition First Edition published 2007 Katipo Books, PO Box 377, Christchurch, Aotearoa/New Zealand. www.katipo.net.nz [email protected] Please visit our website to check our catalogue of books. Irrecuperable Press, PO Box 6387, Wellington, Aotearoa/New Zealand. [email protected] www.rabblerousers.co.nz Text © 2008 Toby Boraman for commercial purposes. This text may be freely reproduced for non-commercial purposes. Please inform the author and the publishers at the addresses above of any such use. All images are ©. Any image in this book may not be reproduced in any form without the express permission of the copyright holder of the image. Printed by Rebel Press, PO Box 9263, Te Aro, Wellington, Aotearoa/New Zealand. www.rebelpress.org.nz [email protected] ISBN 978-0-473-12299-7 Designed by the author. Cover designed by Justine Boraman. Cover photos: (bottom) Dancing during the liberation of Albert Park, Auckland, 1969. Photo by Simon Buis from his The Brutus Festival, p. 6; (left) The Christchurch Progressive Youth Movement, c. 1970, from the Canta End of Year Supplement, 1972. Cover wallpaper: Unnamed wallpaper from Horizons Ready-Pasted Wallpaper Sample Book, Wellington: Ashley Wallcoverings, c. 1970, p. 14. The Sample Book was found in vol. 2 of the Wallpaper Sample Books held in the Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago, Dunedin. -

Chapter 1. When Is Music Political?

Durham E-Theses Music, Civil Rights, and Counterculture: Critical Aesthetics and Resistance in the United States, 1957-1968 BARKER, THOMAS,PATRICK How to cite: BARKER, THOMAS,PATRICK (2016) Music, Civil Rights, and Counterculture: Critical Aesthetics and Resistance in the United States, 1957-1968, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11693/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Music, Civil Rights, and Counterculture: Critical Aesthetics and Resistance in the United States, 1957-1968 Thomas Barker PhD Music Department University of Durham 2016 Music, Civil Rights, and Counterculture: Critical Aesthetics and Resistance in the United States, 1957-1968 Thomas Barker Abstract This dissertation explores the role of music within the politics of liberation in the United States in the period of the late 1950s and the 1960s. Its focus is on the two dominant, but very different (and, it is argued, interconnected) mass political and cultural movements that converged in the course of the 1960s: civil rights and counterculture. -

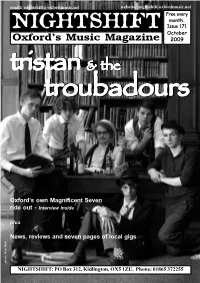

Issue 171.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 171 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2009 tristantristantristantristan &&& thethethe troubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadours Oxford’s own Magnificent Seven ride out - Interview inside plus News, reviews and seven pages of local gigs photo: Marc West photo: Marc NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net THIS MONTH’S OX4 FESTIVAL will feature a special Music Unconvention alongside its other attractions. The mini-convention, featuring a panel of local music people, will discuss, amongst other musical topics, the idea of keeping things local. OX4 takes place on Saturday 10th October at venues the length of Cowley Road, including the 02 Academy, the Bullingdon, East Oxford Community Centre, Baby Simple, Trees Lounge, Café Tarifa, Café Milano, the Brickworks and the Restore Garden Café. The all-day event has SWERVEDRIVER play their first Oxford gig in over a decade next been organised by Truck and local gig promoters You! Me! Dancing! Bands month. The one-time Oxford favourites, who relocated to London in the th already confirmed include hotly-tipped electro-pop outfit The Big Pink, early-90s, play at the O2 Academy on Thursday 26 November. The improvisational hardcore collective Action Beat and experimental hip hop band, who signed to Creation Records shortly after Ride in 1990, split in outfit Dälek, plus a host of local acts. Catweazle Club and the Oxford Folk 1999 but reformed in 2008, still fronted by Adam Franklin and Jimmy Festival will also be hosting acoustic music sessions. -

CLINE-DISSERTATION.Pdf (2.391Mb)

Copyright by John F. Cline 2012 The Dissertation Committee for John F. Cline Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Permanent Underground: Radical Sounds and Social Formations in 20th Century American Musicking Committee: Mark C. Smith, Supervisor Steven Hoelscher Randolph Lewis Karl Hagstrom Miller Shirley Thompson Permanent Underground: Radical Sounds and Social Formations in 20th Century American Musicking by John F. Cline, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my mother and father, Gary and Linda Cline. Without their generous hearts, tolerant ears, and (occasionally) open pocketbooks, I would have never made it this far, in any endeavor. A second, related dedication goes out to my siblings, Nicholas and Elizabeth. We all get the help we need when we need it most, don’t we? Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation supervisor, Mark Smith. Even though we don’t necessarily work on the same kinds of topics, I’ve always appreciated his patient advice. I’m sure he’d be loath to use the word “wisdom,” but his open mind combined with ample, sometimes non-academic experience provided reassurances when they were needed most. Following closely on Mark’s heels is Karl Miller. Although not technically my supervisor, his generosity with his time and his always valuable (if sometimes painful) feedback during the dissertation writing process was absolutely essential to the development of the project, especially while Mark was abroad on a Fulbright. -

Alumni News Alumni and Parents Respond to First Appeal for Funds

<.'-N COLLt , y V(-' < ~P R 25'1'! LIBRARY 21, 1971. "Dennis will be serving as pboeofx: Alumni News Curate at the Church of the Redeemer in Sarasota after his graduation from April1971 Seminary in June." Charlotte (Willis) Mann, 63 Botolph Street, Melrose, Mass. 02176. "We have Alumni and Parents Respond bought a 10 room Victorian house. My husband, William, was recently elected To First Appeal for Funds vice president of his company. I am presently studying flute under Lois Alumni, and parents definitely known to have been influenced by alumni earned the Schaefer of the Boston Symphony college a gift of $525 from Group Captain Hugh M. Groves' one-for-two challenge when Orchestra and am playing in the Melrose they gave New College a total of $1,050 within the Ford Challenge year. Symphony, a community orchestra. Bill Two other gifts totaling $550 arrived just too late to be counted. Group Captain and I have one child, Anita, who will be Groves, an Associate and former trustee, has already renewed his challenge {up to a total two in January." liability of $2,500) for the new Ford year. As a consequence, this additional $550 will earn a matching gift of $225 from Group Captain Groves in 1971. Anna Navaro, 3645 St. Mary's Pl. N. W., Washington D. C. 20007. "I have been in Washington for the last year or so, mostly Class 1967 today. And it's pretty important to me. working for a small political polling firm. What did you do?" In January I accepted an invitation to work as the in-house pollster to Senator Class Correspondents: Maureen (Spear) Tim Dunsworth, Sp 5, 470-56-5403, and Dennis Kezar, School of Theology, Muskie. -

COPIES Strana 1 Z 29 Aktualizované 1.5.2013 | V 1.0 B

COPIES Strana 1 z 29 aktualizované 1.5.2013 | v 1.0 b 0-9 5UU´S HUNGER´S TEETH 5UU´S POINT OF VIEWS 1996 5UU´S REGARDING PURGATORIES 2000 A A JOINT EFFORT / BLACK ORCHIDS FINAL EFFORT / AWOL 1972 A.P.C. /SECTION MUSICALE/ MANIFESTE ABACUS ABACUS 1971 AC/DC IRON MAN 2 /CD+DVD/ 2010 ACID MOTHERS GONG LIVE IN NAGOYA 2003 ACID MOTHERS GURU GURU PSYCHEDELIC NAVIGATOR 2006 ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE/ESCAPADE A THOUSAND SHADES OF GREY 2003 ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE MYTH OF THE LOVE ELECTRIQUE 2006 ACTION ACTION 1972 AERA THE BAVARIAN RADIO/BR/ RECORDINGS VOL. 1 1975 AERA THE BAVARIAN RADIO/BR/ RECORDINGS VOL. 2 1977-79 AFTER TEA JOINTHOUSE BLUES 1970 AGAMENÓN / STEEL RIVER TODOS RÍEN DE MÍ / ´WEITIN´HEAVY´ 1975/70 AGÁPE THE PROBLEM IS SIN LIVE AND UNRELEASED 1968-96 AGGREGATION MIND ODYSSEY 1967 AGITATION FREE AT THE CLIFFS OF RIVER RHINE 1974 AGITATION FREE THE OTHER SIDES OF AGITATION FREE 1974 AGITATION FREE FRAGMENTS 1974 AGITATION FREE LIVE ´74 1974 AGITATION FREE SHIBUYA NIGHTS LIVE IN TOKYO 2007 AGNES STRANGE THEME FOR A DREAM 1972/74 AGREN, JIMMY GLASS FINGER GHOST 2000 AGREN, JIMMY/NO MAN GET THIS INTO YOUR HEAD/((SPEAK)) 1996 AIGUES VIVES WATER OF SEASONS 1981 AL SIMONES CORRIDOR OF DREAMS / ENCHANTED FOREST /2CD/ 1992/97 ALAMO ALAMO 1971 ALBATROS GARDEN OF EDEN 1978 ALESINI + ANDREONI MARCO POLO ALESINI + ANDREONI MARCO POLO II ALEXANDER´S TIMELESS BLOOZBANDFOR SALE 1968 ALGARNAS TRADGARD/GARDEN OF THEFRAMTIDEN ELKS/ AR ETT SVAVANDE SKEPP,FORANKRAT I 1972 ALICE ALICE 1970 ALL SAVED FREAK BAND BRAINWASHED 1976 ALL SAVED FREAK BAND SOWER ALLEN, DAEVID AND THE MAGICK BROTHERSLIVE AT THE WITCHWOOD 1991 AME SON CATALYSE 1994 AMPHYRITE AMPHYRITE 1973 AMYGDALA COMPLEX COMBAT 2008 COPIES Strana 1 z 29 aktualizované 1.5.2013 | v 1.0 b COPIES Strana 2 z 29 aktualizované 1.5.2013 | v 1.0 b ANABIS HEAVEN ON EARTH ANALOGY 25 YEARS LATER 1996 ANDWELLA´S DREAM LOVE AND POETRY 1969 ANEKDOTEN NUCLEUS ANGE EMILE JACOTEY 1975 ANGE GUET-APENS 1978 ANONIMA SOUND LTD. -

This Is How We Do: Living and Learning in an Appalachian Experimental Music Scene

THIS IS HOW WE DO: LIVING AND LEARNING IN AN APPALACHIAN EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC SCENE A Thesis by SHANNON A.B. PERRY Submitted to the Graduate School Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS MAY 2011 Center for Appalachian Studies THIS IS HOW WE DO: LIVING AND LEARNING IN AN APPALACHIAN EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC SCENE A Thesis by SHANNON A.B. PERRY May 2011 APPROVED BY: ________________________________ Fred J. Hay Chairperson, Thesis Committee ________________________________ Susan E. Keefe Member, Thesis Committee ________________________________ Patricia D. Beaver Member, Thesis Committee ________________________________ Patricia D. Beaver Director, Center for Appalachian Studies ________________________________ Edelma D. Huntley Dean, Research and Graduate Studies Copyright by Shannon A.B. Perry 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT THIS IS HOW WE DO: LIVING AND LEARNING IN AN APPALACHIAN EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC SCENE (2011) Shannon A.B. Perry, A.B. & B.S.Ed., University of Georgia M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Fred J. Hay At the grassroots, Appalachian music encompasses much more than traditional music genres, like old-time and bluegrass. While these prevailing musics continue to inform most popular and scholarly understandings of the region’s musical heritage, many contemporary scholars dismiss such narrow definitions of “Appalachian music” as exclusionary and inaccurate. Many researchers have, thus, sought to broaden current understandings of Appalachia’s diverse contemporary and historical cultural landscape as well as explore connections between Appalachian and other regional, national, and global cultural phenomena. In April 2009, I began participant observation and interviewing in an experimental music scene unfolding in downtown Boone, North Carolina. -

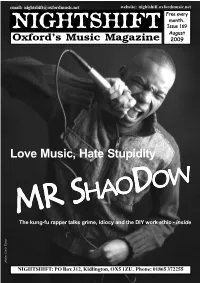

Issue 169.Pmd

email: [email protected] NIGHTSHIFTwebsite: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Oxford’s Music Magazine Free every month. Issue 169 August 2009 Love Music, Hate Stupidity MRMRMR SSSHAOHAOHAODDDOWOWOW The kung-fu rapper talks grime, idiocy and the DIY work ethic - inside photo: Louis Taylor NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 www.theunsignedguide.com next month’s issue. FAT LIL’S in Witney hosts an all- AS EVER, don’t forget to tune into NEWNEWSS day free mini-festival on Sunday BBC Oxford Introducing every NEWNEWSS th 30 August. Lil-Lapolooza will Saturday evening between 6-7pm. Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU feature an assortment of local indie The dedicated local music show Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] and metal bands from 1pm features the best new local releases, Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net onwards. Visit www.fatlils.co.uk interviews, demos and gig guide. for line-up details. The show is available to listen to online all week at bbc.co.uk/oxford. THE NIGHTSHIFT ONLINE details for free. Visit TRUCK will follow up July’s FORUM now features an nightshift.oxfordmusic.net. festival with a special one-day A REMINDER to all venues, clubs interactive local music directory. celebration of the local music scene etc. about the Academy’s alternative The directory features contact THE UNSIGNED GUIDE on Saturday 10th October. OX4 will freshers fair which takes place on details for local bands, studios, launches its new website this feature gigs and music workshops Wednesday 23rd September. Anyone promoters, web designers, van hire, month, offering a guide to unsigned at various venues along Cowley interested in taking part should magazines, record labels and more.