Joseph Saxton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

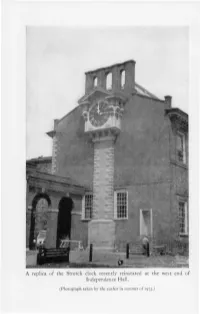

A Replica of the Stretch Clock Recently Reinstated at the West End of Independence Hall

A replica of the Stretch clock recently reinstated at the west end of Independence Hall. (Photograph taken by the author in summer of 197J.) THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY The Stretch Qlock and its "Bell at the State House URING the spring of 1973, workmen completed the construc- tion of a replica of a large clock dial and masonry clock D case at the west end of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the original of which had been installed there in 1753 by a local clockmaker, Thomas Stretch. That equipment, which resembled a giant grandfather's clock, had been removed in about 1830, with no other subsequent effort having been made to reconstruct it. It therefore seems an opportune time to assemble the scattered in- formation regarding the history of that clock and its bell and to present their stories. The acquisition of the original clock and bell by the Pennsylvania colonial Assembly is closely related to the acquisition of the Liberty Bell. Because of this, most historians have tended to focus their writings on that more famous bell, and to pay but little attention to the hard-working, more durable, and equally large clock bell. They have also had a tendency either to claim or imply that the Liberty Bell and the clock bell had been procured in connection with a plan to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary, or "Jubilee Year," of the granting of the Charter of Privileges to the colony by William Penn. But, with one exception, nothing has been found among the surviving records which would support such a contention. -

Joseph Henry

MEMOIR JOSEPH HENRY. SIMON NEWCOMB. BEAD BEFORE THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OP SCIENCES, APRIL 21, 1880. (1) BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF JOSEPH HENRY. In presenting to the Academy the following notice of its late lamented President the writer feels that an apology is due for the imperfect manner in which he has been obliged to perform the duty assigned him. The very richness of the material has been a source of embarrassment. Few have any conception of the breadth of the field occupied by Professor Henry's researches, or of the number of scientific enterprises of which he was either the originator or the effective supporter. What, under the cir- cumstances, could be said within a brief space to show what the world owes to him has already been so well said by others that it would be impracticable to make a really new presentation without writing a volume. The Philosophical Society of this city has issued two notices which together cover almost the whole ground that the writer feels competent to occupy. The one is a personal biography—the affectionate and eloquent tribute of an old and attached friend; the other an exhaustive analysis of his scientific labors by an honored member of the society well known for his philosophic acumen.* The Regents of the Smithsonian Institution made known their indebtedness to his administration in the memorial services held in his honor in the Halls of Congress. Under these circumstances the onl}*- practicable course has seemed to be to give a condensed resume of Professor Henry's life and works, by which any small occasional gaps in previous notices might be filled. -

A Chronological History of Electrical Development from 600 B.C

From the collection of the n z m o PreTinger JJibrary San Francisco, California 2006 / A CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY OF ELECTRICAL DEVELOPMENT FROM 600 B.C. PRICE $2.00 NATIONAL ELECTRICAL MANUFACTURERS ASSOCIATION 155 EAST 44th STREET NEW YORK 17, N. Y. Copyright 1946 National Electrical Manufacturers Association Printed in U. S. A. Excerpts from this book may be used without permission PREFACE presenting this Electrical Chronology, the National Elec- JNtrical Manufacturers Association, which has undertaken its compilation, has exercised all possible care in obtaining the data included. Basic sources of information have been search- ed; where possible, those in a position to know have been con- sulted; the works of others, who had a part in developments referred to in this Chronology, and who are now deceased, have been examined. There may be some discrepancies as to dates and data because it has been impossible to obtain unchallenged record of the per- son to whom should go the credit. In cases where there are several claimants every effort has been made to list all of them. The National Electrical Manufacturers Association accepts no responsibility as being a party to supporting the claims of any person, persons or organizations who may disagree with any of the dates, data or any other information forming a part of the Chronology, and leaves it to the reader to decide for him- self on those matters which may be controversial. No compilation of this kind is ever entirely complete or final and is always subject to revisions and additions. It should be understood that the Chronology consists only of basic data from which have stemmed many other electrical developments and uses. -

Superintendent's Annual Narrative Report, Independence National

Note the following: Page 15: Partnerships - “A challenge INDE faced in 2007 was finalizing long-term agreements with both the Independence Visitor Center Corporation (IVCC) and the National Constitution Center (NCC). Because of the complexity of these agreements, they are still under review in the Departments Office of the Solicitor. The IVCC and NCC continue to operate under Special Use Permits.” Page 16: Cooperating Agreement - “In 2007, INDE managed 12 Commercial Use Permits…The park successfully worked with the IVCC to respond to complaints from tour operators, who are competing for prime locations within the building to advertise their tours. While this problem will likely persist until the space within the Independence Visitor Center has been reorganized a project that will take place during 2008 through a series of meetings with the tour operators the park is continuing to address their concerns.” INDEPENDENCE NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK SUPERINTENDENT’S ANNUAL NARRATIVE REPORT October 1, 2006 – September 30, 2007 Introduction The Superintendent and staff of Independence National Historical Park (INDE) share the stewardship of some of the most important symbols of our nation’s heritage: the Liberty Bell, Independence Hall, Congress Hall and Franklin Court. They also share responsibility for Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site (EDAL), Thaddeus Kosciuszko National Memorial (THKO) and Gloria Dei (Old Swedes’) Church National Historic Site (GLDE). Independence National Historical Park continued to work on several multi-year, multi-faceted projects including the commemoration of the President’s House Site, the security plan for the Liberty Bell Center and Independence Square, the Long Range Interpretive Plan, the rehabilitation of Franklin Court and finalizing partnership agreements. -

Origin of the Electric Motor

Origin of the Electric Motor JOSEPH C. MIGHALOWICZ MEMBER AIEE HE DAY that man Had it not been for the efforts of men like 1821—Michael Faraday dem- T molded the first wheel Davenport, De Jacobi, and Page, the benefits onstrated for the first time the from the sledlike skids of his of the electric motor would not be enjoyed possibility of motion by electro- magnetic means with the move- primitive wagon should be today. It is the purpose of this article to trace ment of a magnetic needle in a one of great commemoration, briefly the early history of the science of electro- field of force. had not its identity been lost motion and, in particular, to bring to light and 1829—-Joseph Henry, a teacher in the passing of time. Not to honor the inventor of the electric motor. of physics at the Albany Academy unlike the wheel and prob- in New York, constructed an elec- ably second only to the wheel, tromagnetic oscillating motor but considered it only a "philosophical the electric motor has been a toy." great benefactor to man and its history, too, slowly is 1833—Joseph Saxton, an American inventor, exhibited a magneto- being forgotten. Today, we hear very little, if anything, about Thomas Figure 1. Thomas Davenport, the blacksmith who invented the electric Davenport, inven- motor; or about De Jacobi, who propelled the first boat tor of the electric by means of an electric motor; or of Charles Page who motor successfully carried passengers on the first practical electric railway. Had it not been for the efforts of these men and others like them, the benefits of the electric motor probably would not be enjoyed today. -

A Fig for Your Philosophy and Great Knowledge in the Sciences

Nagle 1 jeff Nagle Professors Dorsey & Minkin History 91 December 17,2011 A Fig For Your Philosophy and Great Knowledge in the Sciences: Observation, Deception, Scientific Fraud and Social Authority in the Antebellum Museum Abstract: There is an increasingly sophisticated literature on the role played by museums in reaffirming social norms of examination in the antebellum United States. This literature has largely focused on the way museums presented this knowledge to the public, not how audiences reacted to claims of scientific authority. Popular reaction to pseudoscientific claims demonstrated to the public in the scientific context of museums, in this case Charles Redheffer's 1812 perpetual motion device and P. T. Barnum's Fejee Mermaid, shed light on the close relationship between early popular scientific observation and ways of judging authenticity and deception in the commercial and social realms of the antebellum period. Have you travelled thro' the pages afthe Natural Historian? come and satisfyyour mind) that he has not deceived you. Come and look nature in the face, andyou will be more highly delighted and satisfied than by historic description. Have you) at any time) read ofbeings whose existence you doubted? call at this repository. Your doubts will vanish) and before you depart your mind may receive impressions emanently conductive to morality and virtue. Those who have no leisure to read) may) at a trifling expence, furnish themselves with a considerable portion ofknowledge--a species ofknowledge that may be found necessary -

Energy, Power, and Transport

Frontispiece Advanced Lunar Base In this panorama of an advanced lunar base, the main habitation modules in the background to the right are shown being covered by lunar soil for radiation protection. The modules on the far right are reactors in which lunar soil is being processed to provide oxygen. Each reactor is heated by a solar mirror. The vehicle near them is collecting liquid oxygen from the reactor complex and will transport it to the launch pad in the background, where a tanker is just lifting off. The mining pits are shown just behind the foreground figure on the left. The geologists in the foreground are looking for richer ores to mine. Artist: Dennis Davidson NASA SP-509, vol. 2 Space Resources Energy, Power, and Transport Editors Mary Fae McKay, David S. McKay, and Michael B. Duke Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas 1992 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Scientific and Technical Information Program Washington, DC 1992 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328 ISBN 0-16-038062-6 Technical papers derived from a NASA-ASEE summer study held at the California Space Institute in 1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Space resources : energy, power, and transport / editors, Mary Fae McKay, David S. McKay, and Michael B. Duke. x, 174 p. : ill. ; 28 cm.—(NASA SP ; 509 : vol. 2) 1. Outer space—Exploration—United States. 2. Natural resources. 3. Space industrialization—United States. I. McKay, Mary Fae. II. McKay, David S. III. Duke, Michael B. -

May 2011, Vol. 37 No. 2

· Oseph & Merry Weather's adventure --- Gass descendant's grave discovered Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation I www.lewisandclark.org May 2011 Volume 37, No. 2 THE L&C EXPEDITION'S ''MACKENZIE CONNECTION'' - RA01sSON AND GROSSEILLJERs · (1905), av FREDERICK REMINGTON T HE C ORPS OF DISCOVERY AND THE A RTICLES OF WAR FuRTWANGLER ON J ouRNAL C OPYING AT T RAVELER'S R EST Contents Letters: Gass grandson's grave found 2 President's Message: Busy winter, promising spring 4 Trail Notes: Simple questions, complicated answers 5 Voyages from Montreal 6 How Alexander Mackenzie's 1793 trans-Canada crossing influenced the Lewis and Clark Expedition By H. Cad Camp Journal Copying at Travelers· Rest 14 Comparing the journals of Gass, Ordway, and Whitehouse with those of Lewis and Clark reveals many similarities-and some important differences By Alburt Furtwangler Mackenzie, p. 7 Lewis & Clark and the Articles of War 21 Out of necessity, the captains developed their own harsh but effective system of military justice By William M. Gadin Kids' Corner 28 Oseph of the Corps of Discovery By Betty Bauer ' L&CRoundup 31 N.D. interpretive center; Undaunted Angl~i;s _ :. "\ < Profile . 32 Isaiah Lukens: Mechanical Genius By Michael Carrick Ordway, p. 15 On the cover This majestic painting by Frederick Remington depicts the French explorers Pierre-Esprit Radisson (1636-1710) and his brother-in-law Medard des Grosseilliers {1618-1696) plying wilderness waters1n a canot du maitre ("master's canoe"), the workhorse of the Canadian fur trade. In J. 793, more than a century after Radisson and Grosseilliers and 10 years before Lewis and Clark, the Scottish explorer and fur trader Alexander Mackenzie made use of a canot du maitre in his crossing of the continent. -

November 2002, Vol. 28 No. 4

Contents Letters: Bad River encounter; Crimson Bluffs 2 From the Directors: Spreading the word in Two Med country 3 From the Bicentennial Council: L&C from different perspectives 4 Trail Notes: Eyes and ears along the Lewis & Clark Trail 6 Tales of the Variegated Bear 8 The captains scoffed at the Mandans’ reports of its ferocity — until they tangled with the “turrible” beast on the high Missouri By Kenneth C. Walcheck Grizzlies, p. 8 Meriwether Lewis’s Air Gun 15 His pneumatic wonder amazed the Indians — but was it a single shot weapon or, as new evidence suggests, a repeater? By Michael F. Carrick Neatness Mattered 22 Hair, beards, and the Corps of Discovery By Robert J. Moore, Jr. The Utmost Reaches of the Missouri 29 Two latter-day explorers describe their quest for the river’s “distant fountain,” 100 miles southeast of Lemhi Pass By Donald F. Nell and Anthony Demetriades Reviews 34 Gunmaker Isaiah Lukens, p. 15 Lewis and Clark among the Grizzlies; Or Perish in the Attempt In Brief: Wheeler, McMurtry, Gass, Best Little Stories L&C Roundup 38 New leadership; kudos; President Bush on Corps of Discovery Gary Moulton’s White House remarks 44 Annual meeting photo spread: Louisville, July 2002 48 On the cover John F. Clymer’s painting Hasty Retreat dramatically depicts one of the many encounters between members of the Corps of Discovery and grizzly bears on the upper Missouri. For more on the explorers’ travails with the variegated bear, see Kenneth Walcheck’s article beginning on page 8 and the review of Paul Schullery’s new book on page 34. -

Expanding the Envelope: Partnering for Transformation

25–29 JUNE 2018 ATLANTA, GEORGIA EXPANDING THE ENVELOPE: PARTNERING FOR TRANSFORMATION See what’s in on page 23. aviation.aiaa.org/thehubschedule aviation.aiaa.org #aiaaAviation BOLDLY INNOVATE Every member of the Skunk Works® team is committed to discovery. No matter the role, each individual’s talent enhances an approach that’s simple: engineer with purpose, innovate with passion and define the future. After 75 years, we continue our mission of developing disruptive technologies to give our customers an absolute advantage. Skunk Works embraces bold innovation. It’s who we are. LOCKHEED MARTIN SEVENTY- FIFTH SKUNK WORKS ANNIVERSARY © 2018 LOCKHEED MARTIN CORPORATION Live: n/a Trim: H: 11in W: 8.5in Job Number: FG18-03724_003 Bleed: .25in all sides Designer: David Gordon / Daniel Buck Publication: AIAA Gutter: None Communicator: Ryn Alford Visual: Low Book Flight Deomnstrator Resolution: 300 DPI Due Date: 5/30/18 Country: USA Density: 300 Color Space: CMYK NETWORK NAME: AIAA Aviation BOLDLY ON-SITE Wi-Fi PASSWORD: aviation18 INNOVATE › Every member of the Skunk Works® team is committed to discovery. No matter the role, each individual’s talent enhances an approach that’s simple: engineer with purpose, innovate with passion and define the future. After 75 years, we continue CONTENTS our mission of developing disruptive technologies to give our customers an absolute advantage. Organizing Committee .................................................................................................. 2 Welcome .......................................................................................................................... -

The American Air Gun School of 1800-1830 By: H

The American Air Gun School of 1800-1830 by: H. M. Stewart When the Pilgrims stepped on the Rock in 1620 did they :arry those blunderbusses we see pictured? How about air :uns? My expert friend, Chuck Suydam, joins most of us n ruling out the blunderbuss, but there could have been iir guns. Marin Le Bourgeoys of Lisieux, France, demon- itrated his air gun to Henry I1 of Navarre in 1602. At the 1976 Valley Forge ASAC meeting practically all the active nterested members were present for my discussion on 'hiladelphia air guns. I spent nearly an hour covering the ~riorstate of the art, the types of arms, and, what mpressed them most, the deadly efficiency of these early Neapons. They were not the BB rifle you played with as a tid: these penetrated 2% inches of pine while the Kentucky ifle, in comparison, did 2% inches! For those of you who ~ouldhave liked to be at Valley Forge, I recommend <ldon Wolff's AIR GUNS for this background. In particu- ar, I urge Dr. Jim, who sent me the BB marksman's button o alibi his New Orleans Anesthesic Adventure, that this )e required reading! Most of the guns physically used in The second publicity of the air gun in my context is the ny talk are pictured in Eldon's AIR GUNS, which is Girardini Austrian military model of 1780 with its bullet ~btainablefrom the Milwaukee Museum for a few dollars. magazine for 20 balls on the right side of the barrel breech. ;pace in the JOURNAL will be saved if you read and I chose as my example of this a model by M. -

L'invention Du Moteur Synchrone Par Nikola Tesla

Bibnum Textes fondateurs de la science Sciences de l’ingénieur L’invention du moteur synchrone par Nikola Tesla Ilarion Pavel Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/bibnum/907 ISSN : 2554-4470 Éditeur FMSH - Fondation Maison des sciences de l'homme Référence électronique Ilarion Pavel, « L’invention du moteur synchrone par Nikola Tesla », Bibnum [En ligne], Sciences de l’ingénieur, mis en ligne le 07 janvier 2013, consulté le 19 avril 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/bibnum/907 © BibNum L'invention du moteur synchrone par Nikola Tesla par Ilarion Pavel ingénieur en chef des mines chercheur au Laboratoire de Physique Théorique École Normale Supérieure Figure 1 : La couverture du Time Magazine du 20 juillet 1931, consacrée à Tesla à l’occasion de son 75e anniversaire (© Time Magazine, New York) Nikola Tesla (1856-1943) est né en Croatie à Smilijan, dans l'Empire d'Autriche, quatrième des cinq enfants d'un prêtre orthodoxe serbe. Après ses études à l'Ecole Polytechnique de Graz et à l'Université de Prague, il travaille comme ingénieur à Budapest et à Paris, où il essaie de développer ses idées sur le courant alternatif et le moteur électrique à champ tournant, sans succès. En 1884, il émigre aux États-Unis où il vivra le reste de sa vie. Il entre dans la compagnie d'électricité fondée par Thomas Edison (1847-1931), mais ce dernier, ayant développé ses affaires exclusivement sur le courant continu, ne voit pas d'un bon œil les idées du jeune Serbe. Déçu, Tesla quitte Edison pour la société de George Westinghouse (1846-1914).