“A Clock for the Rooms”: the Library Company's Horological Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics Is a Gentleman's Art: Analysis and Synthesis in American College Geometry Teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2000 Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K. Ackerberg-Hastings Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Ackerberg-Hastings, Amy K., "Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 " (2000). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 12669. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/12669 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margwis, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Prague & Munich

Prague & Munich combo weekend! A chance to enjoy two of the most beauful, historic and largest beer consuming places on the planet in one weekend! Prague - The golden city, incredible architecture and sights, Charles bridge, Prague castle (the largest in the world), the ancient Jewish quarter, Easter European prices, Starbucks and other western food chains, wild nightlife & Czech Beer (pints for $1). Surely one of the most intriguing cies in the world as well as one of the most excing in Europe, Prague is a trip not to be missed! Munich - The land of lederhosen, pretzels and beer – and Oktoberfest! This famous Bavarian city as all of the culture, history, museums and of course beer to make it one of the world’s greatest cies! Munich’s reputaon for being Europe’s most fun city is well-deserved, as no maRer what season or me of year, there’s always a reason for a celebraon! Country: Prague - Czech Republic (Czechia); Munich - Germany Language Prague - Czech; Munich - German Currency Prague - Czech Koruna; Munich - Euro Typical Cuisine Prague - Pork, beef, dumplings, potatoes, beer hot spiced wine, Absinthe, Czech Beer. Munich - wurst (sausage), Pretzels, krautsalat (sauerkrautsalad), kartoffelsalat (potato salad) schweinshaxe (roasted pork knuckle), schnitzel, hendl (roasted chicken), strudels, schnapps, beer. Old Town Square, Lennon Wall, Wenceslas Square, Jewish Quarter, Astronomical Clock, Charles Bridge, Prague Castle. Must see: Prague - Old Town Square, Lennon Wall, Wenceslas Square, Jewish Quarter, Astronomical Clock, Charles Bridge, Prague Castle.. Munich - Horauhaus, Glockenspiel, English gardens, Beer Gardens DEPARTURE TIMES DEPARTURE CITIES Thursday Florence Florence - 8:00 pm Rome Rome - 5:00 -5:30 pm Fly In - meet in Prague Sunday Return Florence - very late Sunday night Rome - very late Sunday night/ early Monday morning WWW.EUROADVENTURES.COM What’s included Full Package: Transportation Only Package: Fly In Package: - round trip transportaon - round trip transportaon - 2 nights accommodaon in Prague - 1 night accomm. -

Grandfathers' Clocks: Their Making and Their Makers in Lancaster County

GRANDFATHERS' CLOCKS: THEIR MAKING AND THEIR MAKERS IN LANCASTER COUNTY, Whilst Lancaster county is not the first or only home of the so-called "Grandfathers' Clock," yet the extent and the excellence of the clock industry in this type of clocks entitle our county to claim special distinction as one of the most noted centres of its production. I, therefore, feel the story of it specially worthy of an enduring place in our annals, and it is with pleasure •and patriotic enthusiasm that I devote the time and research necessary to do justice to the subject that so closely touches the dearest traditions of our old county's social life and surroundings. These old clocks, first bought and used by the forefathers of many of us, have stood for a century or more in hundreds of our homes, faithfully and tirelessly marking the flight of time, in annual succession, for four genera- tions of our sires from the cradle to the grave. Well do they recall to memory and imagination the joys and sorrows, the hopes and disappointments, the successes and failures, the ioves and the hates, hours of anguish, thrills of happiness and pleasure, that have gone into and went to make up the lives of the lines of humanity that have scanned their faces to know and note the minutes and the hours that have made the years of each succeeding life. There is a strong human element in the existence of all such clocks, and that human appeal to our thoughts and memories is doubly intensified when we know that we are looking upon a clock that has thus spanned the lives of our very own flesh and blood from the beginning. -

Eastern Europe and Baltic Countries

English Version EASTERN EUROPE AND BALTIC COUNTRIES GRAND TOUR OF POLAND IMPERIAL CAPITALS GRAND TOUR OF THE BALTIC COUNTRIES GDANSK MALBORK TORUN BELARUS GRAND TOUR OF POLAND WARSAW POLAND GERMANY WROCLAW CZESTOCHOWA KRAKOW CZECH REPUBLIC WIELICZKA AUSCHWITZ UKRAINE SLOVAKIA Tour of 10 days / 9 nights AUSTRIA DAY 1 - WARSAW Arrival in Warsaw and visit of the Polish capital, entirely rebuilt after the Second World War. Dinner and accommodation.SUISSE DAY 2 - WARSAW Visit of the historic center of Warsaw: the Jewish Quarter, Lazienkowski Palace, the Royal route. In the afternoon, visit of the WarsawMILANO Uprising Museum, dedicated to the revolt of the city during World War II. Dinner and accommodation. FRANCE DAY 3 - WARSAW / MALBORKGENOA / GDANSK PORTO FINO Departure for the Baltic Sea. Stop for a visit of the Ethnographic Museum with its typical architecture. Continue withNICE a visit of the Fortress of Malbork listed at the UNESCO World Heritage Site. Then, CANNES departure for Gdansk. Dinner and accommodation.ITALIE DAY 4 - GDANSK / GDNIA / SOPOT / GDANSK City tour of Gdansk. Go through the Golden Gate, a beautiful street with Renaissance and Baroque facades, terraces and typical markets, the Court of Arthus, the Neptune Fountain and finally the Basilica Sainte Marie. Continue to the famous resort of Sopot with its elegant houses, also known as the Monte Carlo of the Baltic Sea. Dinner and accommodation. DAY 5 - GDANSK / TORUN / WROCLAW Departure for Torun, located on the banks of the Vistula and hometown of the astronomer Nicolas Copernicus. Guided tour of the historical center and visit the house of Copernicus. Departure to Wroclaw. -

A Political Perch: a Historical Analysis and Online Exhibit of the U.S. Senate Clerk's Desk

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects Honors College at WKU 2020 A Political Perch: A Historical Analysis and Online Exhibit of the U.S. Senate Clerk's Desk Olivia Bowers Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Museum Studies Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Bowers, Olivia, "A Political Perch: A Historical Analysis and Online Exhibit of the U.S. Senate Clerk's Desk" (2020). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 838. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/838 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A POLITICAL PERCH: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS AND ONLINE EXHIBIT OF THE U.S. SENATE CLERK’S DESK A Capstone Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts with Mahurin Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky University By Olivia R. Bowers May 2020 ***** CE/T Committee: Dr. Guy Jordan, Chair Prof. Kristina Arnold Dr. Jennifer Walton-Hanley Copyright by Olivia R. Bowers 2020 I dedicate this thesis to my parents, Clinton and Dawn Bowers, for teaching me that pursuing my dreams can help others in the process. I would also like to thank Dr. Guy Jordan, a teacher, mentor, and friend, for believing in me and encouraging me to aim for the seemingly impossible. -

The Rebirth of Swiss Watch Brand Angelus

The rebirth of Swiss watch brand Angelus After lying dormant for more than 30 years, Angelus has now been revived by Manufacture La Joux-Perret, which has spent four years developing the next generation of visionary timepieces. The Angelus’ manufacture in La Chaux-de-Fonds is just a stone’s throw from where the Stolz brothers established their original manufacture. Dating back nearly 125 years, Angelus has been one of the most influential horological manufactures of the last century. Connoisseurs of high-end watchmaking have universally hailed Angelus' pioneering, in-house developed movements and timepieces, which continue to be coveted by collectors all over the world. Angelus was founded in 1891 by the brothers Albert and Gustav Stolz with the establishment of the Angelus watchmaking manufacture in Le Locle, Switzerland. Chronodato 1942 Angelus launches the world's first series chronograph with calendar. Initially christened the Chronodate, then Chronodato from 1943 onwards. © ANGELUS SA Over the past century, Angelus forged a fine reputation for creating exceptional chronograph and multi-complication wristwatches, multi-display travel clocks with long power reserves, and alarm watches. The brand marked several firsts along the way, including the Chronodato (1942), which was the first series wristwatch chronograph with calendar. The Chrono-Datoluxe (1948) featured the very first big date in a chronograph wristwatch; it was also the first series chronograph wristwatch with a digital calendar – years before such a display became a standard in watchmaking. The Datalarm (1956) was the first wristwatch ever featuring both alarm and date function, while the cult timepiece the Tinkler (1958) was both the first automatic repeater wristwatch and also the first fully waterproof repeater wristwatch. -

Th B T the Brocots

The BtBrocots A Dyyynasty of Horologers Presented by John G. Kirk 1 Outline • Introduction • Background: Paris Clocks • Brocot GlGenealogy • The Men and Their Works • Gallery 2 Outline • Introduction • Background: Paris Clocks • Brocot GlGenealogy • The Men and Their Works • Gallery 3 Introduction • This is a review of “Les Brocot, une dynastie d’ horlogers” by Richard Chavigny • Dean Armentrout asked me to discover the following: – How many/who are the Brocots who contributed to horology (see below…) – The years the famous innovations were made (and by whom) (see below…) – How the Brocot dynasty interacted with other clockmakers, for example the house of Le Roy (i(curious ly, such iitnterac tions, if any, aren’t mentioned in the book) 4 Outline • Introduction • Background: Paris Clocks • Brocot GlGenealogy • The Men and Their Works • Gallery 5 The Paris Clock (1 of 5) • The term, la Pendule de Paris, applies to table/mantel clocks developed by Parisian clockmakers • Beginning around 1810 and continuing well into the 20th century production of these clocks evolved into a highly industrialized process 6 The Paris Clock (2 of 7) • Around 1810, Paris clocks were no longer fabricated from scratch in Paris except by the grand houses, such as Breguet, Le Paute, etc. • A “mass” market for high quality, competitively‐priced “Clocks of Commerce” developed based on ébauches completed and finished in Paris 7 The Paris Clock (3 of 7) • The ébauches comprised – The two plates – The barrel (without spring) – The stiktrike titrain compltlete with dtdeten -

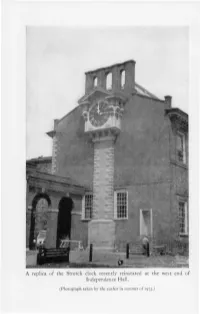

A Replica of the Stretch Clock Recently Reinstated at the West End of Independence Hall

A replica of the Stretch clock recently reinstated at the west end of Independence Hall. (Photograph taken by the author in summer of 197J.) THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY The Stretch Qlock and its "Bell at the State House URING the spring of 1973, workmen completed the construc- tion of a replica of a large clock dial and masonry clock D case at the west end of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the original of which had been installed there in 1753 by a local clockmaker, Thomas Stretch. That equipment, which resembled a giant grandfather's clock, had been removed in about 1830, with no other subsequent effort having been made to reconstruct it. It therefore seems an opportune time to assemble the scattered in- formation regarding the history of that clock and its bell and to present their stories. The acquisition of the original clock and bell by the Pennsylvania colonial Assembly is closely related to the acquisition of the Liberty Bell. Because of this, most historians have tended to focus their writings on that more famous bell, and to pay but little attention to the hard-working, more durable, and equally large clock bell. They have also had a tendency either to claim or imply that the Liberty Bell and the clock bell had been procured in connection with a plan to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary, or "Jubilee Year," of the granting of the Charter of Privileges to the colony by William Penn. But, with one exception, nothing has been found among the surviving records which would support such a contention. -

Pioneers in Optics: Christiaan Huygens

Downloaded from Microscopy Pioneers https://www.cambridge.org/core Pioneers in Optics: Christiaan Huygens Eric Clark From the website Molecular Expressions created by the late Michael Davidson and now maintained by Eric Clark, National Magnetic Field Laboratory, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306 . IP address: [email protected] 170.106.33.22 Christiaan Huygens reliability and accuracy. The first watch using this principle (1629–1695) was finished in 1675, whereupon it was promptly presented , on Christiaan Huygens was a to his sponsor, King Louis XIV. 29 Sep 2021 at 16:11:10 brilliant Dutch mathematician, In 1681, Huygens returned to Holland where he began physicist, and astronomer who lived to construct optical lenses with extremely large focal lengths, during the seventeenth century, a which were eventually presented to the Royal Society of period sometimes referred to as the London, where they remain today. Continuing along this line Scientific Revolution. Huygens, a of work, Huygens perfected his skills in lens grinding and highly gifted theoretical and experi- subsequently invented the achromatic eyepiece that bears his , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at mental scientist, is best known name and is still in widespread use today. for his work on the theories of Huygens left Holland in 1689, and ventured to London centrifugal force, the wave theory of where he became acquainted with Sir Isaac Newton and began light, and the pendulum clock. to study Newton’s theories on classical physics. Although it At an early age, Huygens began seems Huygens was duly impressed with Newton’s work, he work in advanced mathematics was still very skeptical about any theory that did not explain by attempting to disprove several theories established by gravitation by mechanical means. -

“Rare Handcrafts 2021” Exhibition

Press Release Patek Philippe, Geneva June 2021 At its Geneva Salons, Patek Philippe presents the richest “Rare Handcrafts” collection ever to be on display there At its historic headquarters on Rue du Rhône, from June 16 to 26, 2021, the manufacture is showcasing an extensive selection of over 75 pocket watches, wristwatches, dome clocks, and table clocks from its latest rare handcrafts collection. It is a rich range of one-of-a-kind and limited-edition pieces that pay tribute to challenging manifestations of craftsmanship such as manual engraving, grand feu cloisonné enamel, miniature painting on enamel, guilloching, gemsetting, and wood micromarquetry. On this occasion, Patek Philippe is also presenting six new watches from the current collection that are endowed with especially elaborate decorations. Since the early days of mechanical watchmaking, artisans have always invested considerable care in decorating their clocks and watches. Timepieces were mainly beautiful, artistically finished treasures before they advanced to become reliable precision instruments. In Geneva, the individual decorative techniques found fertile ground in the famous “Fabrique” where all watchmaking-related occupations were assembled. Since 1839, as an heir of the grand Genevan tradition, Patek Philippe systematically commissioned the most talented artists to ennoble its creations. From 1970 to 1980, when the demand for such decoratively enhanced watches slumped and several ancestral techniques were on the brink of extinction, the manufacture mobilized its resources to preserve and breathe new life into all of its precious know-how and in particular miniature painting on enamel. Grand passion To this very day, Patek Philippe is dedicated to safeguarding and handing down all these competencies, but also to further evolving them in close collaboration with the artists who set their sights on new horizons. -

On the Isochronism of Galilei's Horologium

IFToMM Workshop on History of MMS – Palermo 2013 On the isochronism of Galilei's horologium Francesco Sorge, Marco Cammalleri, Giuseppe Genchi DICGIM, Università di Palermo, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract − Measuring the passage of time has always fascinated the humankind throughout the centuries. It is amazing how the general architecture of clocks has remained almost unchanged in practice to date from the Middle Ages. However, the foremost mechanical developments in clock-making date from the seventeenth century, when the discovery of the isochronism laws of pendular motion by Galilei and Huygens permitted a higher degree of accuracy in the time measure. Keywords: Time Measure, Pendulum, Isochronism Brief Survey on the Art of Clock-Making The first elements of temporal and spatial cognition among the primitive societies were associated with the course of natural events. In practice, the starry heaven played the role of the first huge clock of mankind. According to the philosopher Macrobius (4 th century), even the Latin term hora derives, through the Greek word ‘ώρα , from an Egyptian hieroglyph to be pronounced Heru or Horu , which was Latinized into Horus and was the name of the Egyptian deity of the sun and the sky, who was the son of Osiris and was often represented as a hawk, prince of the sky. Later on, the measure of time began to assume a rudimentary technical connotation and to benefit from the use of more or less ingenious devices. Various kinds of clocks developed to relatively high levels of accuracy through the Egyptian, Assyrian, Greek and Roman civilizations. -

Vaughn Next Century Learning Center

2020 VAUGHN 2021 NEXT CENTURY LEARNING CENTER July/julio 2020 JULY-JULIO January/enero 2021 S M T W Th F S 1-31 Summer Vacation S M T W Th F S 1 2 3 4 30-31 Staff Development 1 2 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 3 SPED SPED SPED ESY ESY 9 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 AUGUST-AGOSTO 10 ESY ESY ESY ESY ESY 16 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 1 Compact Signing 17 18 ESY ESY ESY ESY 23 26 27 28 29 SD SD 3 Staff Development 24 ESY ESY ESY ESY SPED 30 0 4 FIRST DAY OF SCHOOL 31 August/agosto 2020 0 S M T W Th F S SEPTEMBER-SEPTIEMBRE February/febrero 2021 CS 4 Minimum Day (Comp Time) S M T W Th F S 2 SD 4 5 6 7 8 7 Labor Day Holiday SD 2 3 4 5 6 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 OCTOBER-OCTUBRE 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 5-9 Fall Break 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 30 31 28 20 NOVEMBER-NOVIEMBRE 18 September/septiembre 2020 3 Election Day - No Committee Meeting March/marzo 2021 S M T W Th F S 11 Veteran's Day Holiday S M T W Th F S 1 2 3 4 5 25 Minimum Day (Comp Time) 1 2 3 4 5 6 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 26-27 Thanksgiving Day Holiday 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 DECEMBER-DICIEMBRE 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 27 28 29 30 17 Minimum Day 28 29 30 31 21 18-31 Winter Vacation 20 October/octubre 2020 April/abril 2021 S M T W Th F S JANUARY-ENERO S M T W Th F S 1 2 3 1-6 Winter Vacation 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 4-6, 29 SpEd ESY (ID'd SPED Only) 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 7-28 ESY 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 18 Martin Luther King Jr Holiday 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 No School (Except