Downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's Institutional Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABBREVIATIONS Use. the Reader That

ABBREVIATIONS A. GENERAL Most of these call for no explanation, as they are in everyday use. The reader has already been warned that 'q.v.' does not invariably imply that there is a separate article on the person so indicated—in several instances he must be sought in the general article on his family. Again, the editor has not troubled to insert a 'q.v.' automatically after the name of a person who is so very well known that the reader may confidently assume that the book contains an article on him. Dates (of birth or death) left unqueried may be assumed to rest on authority: whether the authority is invariably correct is another matter. Dates queried indicate that we are merely told (on good authority) that the person concerned, say, 'died at the age of 64'. The form '1676/7' is used for the weeks of 1 January- 25 March in the years preceding the reform of the calendar by the Act of 1751. The 'Sir' (in Welsh, 'Syr') prefixed to a cleric's name in the older period is in practice merely the 'Rev.' of later times. Strictly speaking, it implied that the cleric had not taken the degree of M.A. (when he would have become 'Mr.', or in Welsh 'Mastr'); a 'Sir' might be a B.A., or an undergraduate, or indeed quite frequently a man who had never been near a university. It will be remembered that Shakespeare has 'Sir Hugh Evans' or, again, 'Sir Nathaniel, a curate'. B. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL Sir John Lloyd had issued to contributors a leaflet prescribing the abbreviations to be used in referring to 'a selection of the works most likely to be cited', adding 'contributors will abbreviate the titles of other works, but the abbreviations should not be such as to furnish no clue at all to the reader when read without context'. -

TRINITY COLLEGE Cambridge Trinity College Cambridge College Trinity Annual Record Annual

2016 TRINITY COLLEGE cambridge trinity college cambridge annual record annual record 2016 Trinity College Cambridge Annual Record 2015–2016 Trinity College Cambridge CB2 1TQ Telephone: 01223 338400 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.trin.cam.ac.uk Contents 5 Editorial 11 Commemoration 12 Chapel Address 15 The Health of the College 18 The Master’s Response on Behalf of the College 25 Alumni Relations & Development 26 Alumni Relations and Associations 37 Dining Privileges 38 Annual Gatherings 39 Alumni Achievements CONTENTS 44 Donations to the College Library 47 College Activities 48 First & Third Trinity Boat Club 53 Field Clubs 71 Students’ Union and Societies 80 College Choir 83 Features 84 Hermes 86 Inside a Pirate’s Cookbook 93 “… Through a Glass Darkly…” 102 Robert Smith, John Harrison, and a College Clock 109 ‘We need to talk about Erskine’ 117 My time as advisor to the BBC’s War and Peace TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 3 123 Fellows, Staff, and Students 124 The Master and Fellows 139 Appointments and Distinctions 141 In Memoriam 155 A Ninetieth Birthday Speech 158 An Eightieth Birthday Speech 167 College Notes 181 The Register 182 In Memoriam 186 Addresses wanted CONTENTS TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 4 Editorial It is with some trepidation that I step into Boyd Hilton’s shoes and take on the editorship of this journal. He managed the transition to ‘glossy’ with flair and panache. As historian of the College and sometime holder of many of its working offices, he also brought a knowledge of its past and an understanding of its mysteries that I am unable to match. -

Pages Ffuglen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page I

Y Meddwl a’r Dychymyg Cymreig FfugLen Y Ddelwedd o Gymru yn y Nofel Gymraeg o Ddechrau’r Chwedegau hyd at 1990 Enid Jones Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru Pages FfugLen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page i FfugLen Pages FfugLen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page ii Y MEDDWL A’R DYCHYMYG CYMREIG Golygydd Cyffredinol John Rowlands Cyfrolau a ymddangosodd yn y gyfres hyd yn hyn: 1. M. Wynn Thomas (gol.), DiFfinio Dwy Lenyddiaeth Cymru (1995) 2. Gerwyn Wiliams, Tir Neb (1996) (Llyfr y Flwyddyn 1997; Enillydd Gwobr Goffa Ellis Griffith) 3. Paul Birt, Cerddi Alltudiaeth (1997) 4. E. G. Millward, Yr Arwrgerdd Gymraeg (1998) 5. Jane Aaron, Pur fel y Dur (1998) (Enillydd Gwobr Goffa Ellis Griffith) 6. Grahame Davies, Sefyll yn y Bwlch (1999) 7. John Rowlands (gol.), Y Sêr yn eu Graddau (2000) 8. Jerry Hunter, Soffestri’r Saeson (2000) (Rhestr Fer Llyfr y Flwyddyn 2001) 9. M. Wynn Thomas (gol.), Gweld Sêr (2001) 10. Angharad Price, Rhwng Gwyn a Du (2002) 11. Jason Walford Davies, Gororau’r Iaith (2003) (Rhestr Fer Llyfr y Flwyddyn 2004) 12. Roger Owen, Ar Wasgar (2003) 13. T. Robin Chapman, Meibion Afradlon a Chymeriadau Eraill (2004) 14. Simon Brooks, O Dan Lygaid y Gestapo (2004) (Rhestr Hir Llyfr y Flwyddyn 2005) 15. Gerwyn Wiliams, Tir Newydd (2005) 16. Ioan Williams, Y Mudiad Drama yng Nghymru 1880–1940 (2006) 17. Owen Thomas (gol.), Llenyddiaeth mewn Theori (2006) 18. Sioned Puw Rowlands, Hwyaid, Cwningod a Sgwarnogod (2006) 19. Tudur Hallam, Canon Ein Llên (2007) Pages FfugLen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page iii Y MEDDWL A’R DYCHYMYG CYMREIG FfugLen Y Ddelwedd o Gymru yn y Nofel Gymraeg o Ddechrau’r Chwedegau hyd at 1990 Enid Jones GWASG PRIFYSGOL CYMRU CAERDYDD 2008 Pages FfugLen:Pages Canon 30/6/08 16:34 Page iv h Enid Jones, 2008 Cedwir pob hawl. -

Amarc-Newsletter-69-October-2017

3 4B 4BNewsletter no. 69 October 2017 Newsletter of the Association for Manuscripts and Archives in Research Collections www.amarc.org.uk STATE AND CITY LIBRARY OF AUGSBURG CELEBRATE 480TH ANNIVERSAIRY State and City Library of Augsburg, Cim 66, ff.5v-6r The arms of the ancestors of Philipp Hainhofer and Regina Waiblinger on a peacock’s fan, miniature from Philipp Hainhofer’s Stammens-Beschreibung, Augsburg, 1626. © By kind permission of the State and City Library of Augsburg. After ten years as the Editor, Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan has handed over responsibility for the AMARC Newsletter to Becky Lawton at the British Library, assisted by Rachael Merrison, archivist at Cheltenham College. The Chairman and committee of AMARC are deeply appreciative of Ceridwen’s labours and of the high quality of the Newsletter and trust that we shall continue to see her at meetings. ISSN 1750-9874 AMARC Newsletter no. 69 October 2017 A unique example of 15th century printed text by English printer William Caxton, discovered in University of Reading Special Collections © By kind permission of the University of Reading Special Collections CONTENTS AMARC matters 2 Grants & Scholarships 16 AMARC meetings 5 Courses 18 Personal 6 Exhibitions 20 MSS News 6 New Accessions 25 Projects 10 Book reviews 29 Lectures 12 New Publications 33 Conferences & Call for 12 Websites 34 Papers AMARC Membership Secretary, AMARC MEMBERSHIP Archivist, The National Gallery Membership can be personal or in- stitutional. Institutional members Trafalgar Square, London, WC2N receive two copies of mailings, 5DN; email: Richard.Wragg@ng- have triple voting rights, and may london.org.uk. -

© 2012 Steven M. Maas

© 2012 Steven M. Maas WELSHNESS POLITICIZED, WELSHNESS SUBMERGED: THE POLITICS OF ‘POLITICS’ AND THE PRAGMATICS OF LANGUAGE COMMUNITY IN NORTH-WEST WALES BY STEVEN M. MAAS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Janet D. Keller, Chair Professor Walter Feinberg Associate Professor Michèle Koven Professor Alejandro Lugo Professor Andrew Orta ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the normative construction of a politics of language and community in north-west Wales (United Kingdom). It is based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted primarily between January 2007 and April 2008, with central participant-observation settings in primary-level state schools and in the teaching-spaces and hallways of a university. Its primary finding is an account of the gap between the national visibility and the cultural (in)visibility communities of speakers of the indigenous language of Wales (Cymraeg, or “Welsh”). With one exception, no public discourse has yet emerged in Wales that provides an explicit framework or vocabulary for describing the cultural community that is anchored in Cymraeg. One has to live those meanings even to know about them. The range of social categories for living those meanings tends to be constructed in ordinary conversations as some form of nationalism, whether political, cultural, or language nationalism. Further, the negatively valenced category of nationalism current in English-speaking Britain is in tension with the positively valenced category of nationalism current among many who move within Cymraeg- speaking communities. Thus, the very politics of identity are themselves political since the line between what is political and what is not, is itself subject to controversy. -

Strange and Terrible Wonders: Climate Change In

STRANGE AND TERRIBLE WONDERS: CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE EARLY MODERN WORLD A Dissertation by CHRISTOPHER RYAN GILSON Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Chester S. L. Dunning Committee Members, R. J. Q. Adams Joseph G. Dawson III Peter J. Hugill Head of Department, David Vaught August 2015 Major Subject: History Copyright 2015 Christopher R. Gilson ABSTRACT The study of climate and climatic change began during the Little Ice Age of the early modern world. Beginning in the sixteenth century, European clerics, scientists, and natural philosophers penned detailed observations of the era’s unusually cool and stormy weather. Scouring the historical record for evidence of similar phenomena in the past, early modern scholars concluded that the climate could change. By the eighteenth century, natural philosophers had identified at least five theories of climatic change, and many had adopted some variation of an anthropogenic explanation. The early modern observations described in this dissertation support the conclusion that cool temperatures and violent storms defined the Little Ice Age. This dissertation also demonstrates that modern notions of climate change are based upon 400 years of rich scholarship and spirited debate. This dissertation opens with a discussion of the origins of “climate” and meteorology in ancient Greek and Roman literature, particularly Aristotle’s Meteorologica. Although ancient scholars explored notions of environmental change, climate change—defined as such—was thought impossible. The translation and publication of ancient texts during the Renaissance contributed to the reexamination of nature and natural variability. -

Jane Williams (Ysgafell) (1806-85) and Nineteenth-Century Welsh Identity

Gwyneth Tyson Roberts Department of English and Creative Writing Thesis title: Jane Williams (Ysgafell) (1806-85) and nineteenth-century Welsh identity SUMMARY This thesis examines the life and work of Jane Williams (Ysgafell) and her relation to nineteenth-century Welsh identity and Welsh culture. Williams's writing career spanned more than fifty years and she worked in a wide range of genres (poetry, history, biography, literary criticism, a critique of an official report on education in Wales, a memoir of childhood, and religious tracts). She lived in Wales for much of her life and drew on Welsh, and Welsh- language, sources for much of her published writing. Her body of work has hitherto received no detailed critical attention, however, and this thesis considers the ways in which her gender and the variety of genres in which she wrote (several of which were genres in which women rarely operated at that period) have contributed to the omission of her work from the field of Welsh Writing in English. The thesis argues that this critical neglect demonstrates the current limitations of this academic field. The thesis considers Williams's body of work by analysing the ways in which she positioned herself in relation to Wales, and therefore reconstructs her biography (current accounts of much of her life are inaccurate or misleading) in order to trace not only the general trajectory of this affective relation, but also to examine the variations and nuances of this relation in each of her published works. The study argues that the liminality of Jane Williams's position, in both her life and work, corresponds closely to many of the important features of the established canon of Welsh Writing in English. -

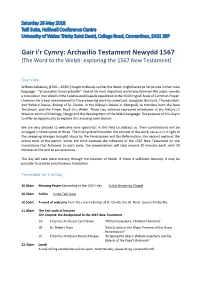

Gair I'r Cymry: Archwilio Testament Newydd 1567

Saturday 26 May 2018 Teifi Suite, Halliwell Conference Centre University of Wales: Trinity Saint David, College Road, Carmarthen, SA31 3EP Gair i’r Cymry: Archwilio Testament Newydd 1567 [The Word to the Welsh: exploring the 1567 New Testament] Overview William Salesbury (1520 – 1599?) fought tirelessly so that the Welsh might have the Scriptures in their own language - “yr yscrythur lan yn ych iaith”. One of his most important works was Kynniver llith a ban, namely a translation into Welsh of the Epistles and Gospels appointed in the 1549 English Book of Common Prayer. However, he is best remembered for the pioneering work he undertook, alongside the cleric, Thomas Huet, and Richard Davies, Bishop of St. Davids, in the Bishop’s Palace in Abergwili, to translate both the New Testament and the Prayer Book into Welsh. These two volumes represent milestones in the history of Wales in terms of theology, liturgy and the development of the Welsh language. The purpose of this day is to offer an opportunity to explore this amazing contribution. We are very pleased to welcome nine specialists in this field to address us. Their contributions will be arranged in three cycles of three. The first cycle will consider the context of the work, set as it is in light of the sweeping changes brought about by the Renaissance and the Reformation; the second explores the actual texts of the period, whilst the third assesses the influence of the 1567 New Testament on the translations that followed. In each cycle, the presentations will take around 20 minutes each, with 30 minutes at the end to ask questions. -

Dr John Dee and the Welsh Context of the Reception of G

provided by Apollo View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by RUSSELL (Paul), « “Divers evidences antient of some Welsh princes”. Dr John Dee and the Welsh context of the reception of Geoffrey of Monmouth in sixteenth-century England and Wales », L’Historia regum e e Britannie et les “Bruts” en Europe. Production, circulation et réception (XII -XVI e e siècle), Tome II, Production, circulation et réception (XII -XVI siècle), p. 395-426 DOI : 10.15122/isbn.978-2-406-07201-0.p.0395 La diffusion ou la divulgation de ce document et de son contenu via Internet ou tout autre moyen de communication ne sont pas autorisées hormis dans un cadre privé. © 2018. Classiques Garnier, Paris. Reproduction et traduction, même partielles, interdites. Tous droits réservés pour tous les pays. © Classiques Garnier e RÉSUMÉ – La réception de l’Historia regum Britannie de Geoffroy de Monmouth au XVI siècle est ici examinée à travers l’œuvre d’un érudit, Dr John Dee. D’origine galloise, Dee fut une figure influente à la cour d’Elisabeth Ie. Il collectionna de nombreux manuscrits et imprimés qu’il passa sa vie à annoter et à comparer. L’Historia et le “Brut” gallois font partie de ses acquisitions. Les notes qu’il a apposées sur leurs témoins sont autant d’indices permettant de comprendre comment il a reçu ces œuvres. ABSTRACT – The reception of Geoffrey’s works in the sixteenth century is examined through the work of one scholar, Dr John Dee; of Welsh origins he was not only an influential figure in the Elizabethan court but also a great collector of manuscripts and printed books which he compared and annotated heavily; they provide us with a useful source for understanding how and from where he acquired his library, his interactions with other scholars, and how he collated the various versions of the works he owned. -

Matthew Parker (1504-1575) Cleaning up After Mary

Image not found Newhttp://go-newfocus.co.uk/images_site/Sites/NewFocus/logo.png Focus Search Menu Matthew Parker (1504-1575) Cleaning Up After Mary George M. Ella | Added: Dec 28, 2005 | Category: Biography A GOLDEN AGE Matthew Parker was the first Reformed Archbishop of Canterbury after the Marian persecutions ended. His task was far from easy as Mary’s tyranny and popish superstitions had left a dirty stain on the entire country. Parker’s person, work, testimony and deep learning, under Providence, enabled England to sweep away the past and embark on a veritable Golden Age for the Church which lasted throughout Elizabeth’s and James’ reigns until brought to a halt in the middle of the following century. I have chosen the term ‘Golden Age’ carefully, not so as to deny the many problems both theological and political that faced England throughout this period but to affirm that hardly any other age since then, including even the Great Awakenings of the 18th century, has been so blessed under such a powerful, widespread ministry of gracious, humble, Christians such as Parker, Coverdale, Whitaker, Jewel, Grindal, Hall, Davenant, Carleton, Ward, Abbot and many more. WOLSEY’S INVITATION HAPPILY REJECTED Our subject was born on 6 August, 1504 in the city of Norwich. His father died before Matthew had reached his teens, leaving the burden of his upbringing and education on his mother’s shoulders. Alice Parker carried that burden well. Matthew was admitted to Bennet College Cambridge at the age of sixteen and quickly gained a scholarship, becoming Bible-Clerk a few months later. -

A Lost Medieval Manuscript from North Wales: Hengwrt 33, the Hanesyn Hên

04 Guy_Studia Celtica 50 06/12/2016 09:34 Page 69 STUDIA CELTICA, L (2016), 69 –105, 10.16922/SC.50.4 A Lost Medieval Manuscript from North Wales: Hengwrt 33, The Hanesyn Hên BEN GUY Cambridge University In 1658, William Maurice made a catalogue of the most important manuscripts in the library of Robert Vaughan of Hengwrt, in which 158 items were listed. 1 Many copies of Maurice’s catalogue exist, deriving from two variant versions, best represented respec - tively by the copies in Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales [= NLW], Wynnstay 10, written by Maurice’s amanuenses in 1671 and annotated by Maurice himself, and in NLW Peniarth 119, written by Edward Lhwyd and his collaborators around 1700. 2 In 1843, Aneirin Owen created a list of those manuscripts in Maurice’s catalogue which he was able to find still present in the Hengwrt (later Peniarth) collection. 3 W. W. E. Wynne later responded by publishing a list, based on Maurice’s catalogue, of the manuscripts which Owen believed to be missing, some of which Wynne was able to identify as extant. 4 Among the manuscripts remaining unidentified was item 33, the manuscript which Edward Lhwyd had called the ‘ Hanesyn Hên ’. 5 The contents list provided by Maurice in his catalogue shows that this manuscript was of considerable interest. 6 The entries for Hengwrt 33 in both Wynnstay 10 and Peniarth 119 are identical in all significant respects. These lists are supplemented by a briefer list compiled by Lhwyd and included elsewhere in Peniarth 119 as part of a document entitled ‘A Catalogue of some MSS. -

Copyrighted Material

PA RT I History COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL CHAPTER 1 Locating the Anglican Communion in the History of Anglicanism Gregory K. Cameron 1867 and All That On September 24, 1867, at 11 o ’ clock in the morning, 76 bishops representing Angli- can and Episcopal Churches across the globe gathered without great ceremony for a quiet said Service of Holy Communion in Lambeth Palace Chapel. They were keenly observed – from outside the Palace – by press and commentators alike, because this was the opening service of the fi rst Lambeth Conference. This gathering of bishops marks the self-conscious birth of the Anglican Communion. Bringing together a college of bishops from around the world, the Conference was a step unprecedented outside the Roman Catholic Church in the second millennium of Christianity, as bishops of three traditions within Anglicanism were consciously gathered together in what we can now recognize as a “Christian World Communion.” 1 The 76 constituted only just over half of the bishops who had been invited, but they had deliberately been invited as being in communion with the See of Canterbury, and they now began to understand themselves as belonging to one family. Groundbreaking as it was, the calling of the fi rst Lambeth Conference by Charles Longley, the 92nd Archbishop of Canterbury, represented the culmination of a process of self-understanding which had been developing rapidly over the previous 100 years. In the previous decades, many had articulated a vision intended to draw the growing diversity of Anglican Churches and dioceses into one fellowship and communion. In a seminal moment some 16 years before, for example, 17 bishops had processed together at the invitation of the then Archbishop of Canterbury, John Sumner, at a Jubilee 1 This term has become widely accepted in the ecumenical world to describe those councils, federations, or gatherings of families of churches which share a common heritage or point of origin, namely, the World Methodist Council (1881), Lutheran World Federation (1947), and the Reformed Ecumenical Council (1946).