University of California, San Diego

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Immigration History

CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) By HOSOK O Bachelor of Arts in History Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 2000 Master of Arts in History University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2010 © 2010, Hosok O ii CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) Dissertation Approved: Dr. Ronald A. Petrin Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael F. Logan Dr. Yonglin Jiang Dr. R. Michael Bracy Dr. Jean Van Delinder Dr. Mark E. Payton Dean of the Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the completion of my dissertation, I would like to express my earnest appreciation to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Ronald A. Petrin for his dedicated supervision, encouragement, and great friendship. I would have been next to impossible to write this dissertation without Dr. Petrin’s continuous support and intellectual guidance. My sincere appreciation extends to my other committee members Dr. Michael Bracy, Dr. Michael F. Logan, and Dr. Yonglin Jiang, whose intelligent guidance, wholehearted encouragement, and friendship are invaluable. I also would like to make a special reference to Dr. Jean Van Delinder from the Department of Sociology who gave me inspiration for the immigration study. Furthermore, I would like to give my sincere appreciation to Dr. Xiaobing Li for his thorough assistance, encouragement, and friendship since the day I started working on my MA degree to the completion of my doctoral dissertation. -

Japan Between the Wars

JAPAN BETWEEN THE WARS The Meiji era was not followed by as neat and logical a periodi- zation. The Emperor Meiji (his era name was conflated with his person posthumously) symbolized the changes of his period so perfectly that at his death in July 1912 there was a clear sense that an era had come to an end. His successor, who was assigned the era name Taisho¯ (Great Righteousness), was never well, and demonstrated such embarrassing indications of mental illness that his son Hirohito succeeded him as regent in 1922 and re- mained in that office until his father’s death in 1926, when the era name was changed to Sho¯wa. The 1920s are often referred to as the “Taisho¯ period,” but the Taisho¯ emperor was in nominal charge only until 1922; he was unimportant in life and his death was irrelevant. Far better, then, to consider the quarter century between the Russo-Japanese War and the outbreak of the Manchurian Incident of 1931 as the next era of modern Japanese history. There is overlap at both ends, with Meiji and with the resur- gence of the military, but the years in question mark important developments in every aspect of Japanese life. They are also years of irony and paradox. Japan achieved success in joining the Great Powers and reached imperial status just as the territo- rial grabs that distinguished nineteenth-century imperialism came to an end, and its image changed with dramatic swiftness from that of newly founded empire to stubborn advocate of imperial privilege. Its military and naval might approached world standards just as those standards were about to change, and not long before the disaster of World War I produced revul- sion from armament and substituted enthusiasm for arms limi- tations. -

Full Download

VOLUME 1: BORDERS 2018 Published by National Institute of Japanese Literature Tokyo EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Editor IMANISHI Yūichirō Professor Emeritus of the National Institute of Japanese 今西祐一郎 Literature; Representative Researcher Editors KOBAYASHI Kenji Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 小林 健二 SAITō Maori Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 齋藤真麻理 UNNO Keisuke Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 海野 圭介 Literature KOIDA Tomoko Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 恋田 知子 Literature Didier DAVIN Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese ディディエ・ダヴァン Literature Kristopher REEVES Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese クリストファー・リーブズ Literature ADVISORY BOARD Jean-Noël ROBERT Professor at Collège de France ジャン=ノエル・ロベール X. Jie YANG Professor at University of Calgary 楊 暁捷 SHIMAZAKI Satoko Associate Professor at University of Southern California 嶋崎 聡子 Michael WATSON Professor at Meiji Gakuin University マイケル・ワトソン ARAKI Hiroshi Professor at International Research Center for Japanese 荒木 浩 Studies Center for Collaborative Research on Pre-modern Texts, National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL) National Institutes for the Humanities 10-3 Midori-chō, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-0014, Japan Telephone: 81-50-5533-2900 Fax: 81-42-526-8883 e-mail: [email protected] Website: https//www.nijl.ac.jp Copyright 2018 by National Institute of Japanese Literature, all rights reserved. PRINTED IN JAPAN KOMIYAMA PRINTING CO., TOKYO CONTENTS -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90w6w5wz Author Carter, Caleb Swift Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Caleb Swift Carter 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries by Caleb Swift Carter Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor William M. Bodiford, Chair This dissertation considers two intersecting aspects of premodern Japanese religions: the development of mountain-based religious systems and the formation of numinous sites. The first aspect focuses in particular on the historical emergence of a mountain religious school in Japan known as Shugendō. While previous scholarship often categorizes Shugendō as a form of folk religion, this designation tends to situate the school in overly broad terms that neglect its historical and regional stages of formation. In contrast, this project examines Shugendō through the investigation of a single site. Through a close reading of textual, epigraphical, and visual sources from Mt. Togakushi (in present-day Nagano Ken), I trace the development of Shugendō and other religious trends from roughly the thirteenth through mid-nineteenth centuries. This study further differs from previous research insofar as it analyzes Shugendō as a concrete system of practices, doctrines, members, institutions, and identities. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

The History Problem: the Politics of War

History / Sociology SAITO … CONTINUED FROM FRONT FLAP … HIRO SAITO “Hiro Saito offers a timely and well-researched analysis of East Asia’s never-ending cycle of blame and denial, distortion and obfuscation concerning the region’s shared history of violence and destruction during the first half of the twentieth SEVENTY YEARS is practiced as a collective endeavor by both century. In The History Problem Saito smartly introduces the have passed since the end perpetrators and victims, Saito argues, a res- central ‘us-versus-them’ issues and confronts readers with the of the Asia-Pacific War, yet Japan remains olution of the history problem—and eventual multiple layers that bind the East Asian countries involved embroiled in controversy with its neighbors reconciliation—will finally become possible. to show how these problems are mutually constituted across over the war’s commemoration. Among the THE HISTORY PROBLEM THE HISTORY The History Problem examines a vast borders and generations. He argues that the inextricable many points of contention between Japan, knots that constrain these problems could be less like a hang- corpus of historical material in both English China, and South Korea are interpretations man’s noose and more of a supportive web if there were the and Japanese, offering provocative findings political will to determine the virtues of peaceful coexistence. of the Tokyo War Crimes Trial, apologies and that challenge orthodox explanations. Written Anything less, he explains, follows an increasingly perilous compensation for foreign victims of Japanese in clear and accessible prose, this uniquely path forward on which nationalist impulses are encouraged aggression, prime ministerial visits to the interdisciplinary book will appeal to sociol- to derail cosmopolitan efforts at engagement. -

The Goddesses' Shrine Family: the Munakata Through The

THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA by BRENDAN ARKELL MORLEY A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts June 2009 11 "The Goddesses' Shrine Family: The Munakata through the Kamakura Era," a thesis prepared by Brendan Morley in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: e, Chair ofthe Examining Committee ~_ ..., ,;J,.." \\ e,. (.) I Date Committee in Charge: Andrew Edmund Goble, Chair Ina Asim Jason P. Webb Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Brendan Arkell Morley IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Brendan A. Morley for the degree of Master ofArts in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies to be taken June 2009 Title: THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA This thesis presents an historical study ofthe Kyushu shrine family known as the Munakata, beginning in the fourth century and ending with the onset ofJapan's medieval age in the fourteenth century. The tutelary deities ofthe Munakata Shrine are held to be the progeny ofthe Sun Goddess, the most powerful deity in the Shinto pantheon; this fact speaks to the long-standing historical relationship the Munakata enjoyed with Japan's ruling elites. Traditional tropes ofJapanese history have generally cast Kyushu as the periphery ofJapanese civilization, but in light ofrecent scholarship, this view has become untenable. Drawing upon extensive primary source material, this thesis will provide a detailed narrative ofMunakata family history while also building upon current trends in Japanese historiography that locate Kyushu within a broader East Asian cultural matrix and reveal it to be a central locus of cultural production on the Japanese archipelago. -

460 Reference

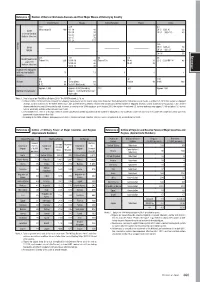

Reference 1 Number of Nuclear Warheads Arsenals and Their Major Means of Delivery by Country United States Russia United Kingdom France China 400 334 60 Minuteman III 400 SS-18 46 DF-5 CSS-4 20 ICBM ( ) SS-19 30 DF-31(CSS-10) 40 (Intercontinental ― ― SS-25 63 Ballistic Missiles) SS-27 78 RS-24 117 Missiles 148 IRBM DF-4(CSS-3) 10 ― ― ― ― MRBM DF-21(CSS-5) 122 DF-26 30 Reference 336 192 48 64 48 SLBM (Submarine Trident D-5 336 SS-N-18 48 Trident D-5 48 M-45 16 JL-2 CSS-NX-14 48 Launched ( ) SS-N-23 96 M-51 48 Ballistic Missiles) SS-N-32 48 Submarines equipped with nuclear ballistic 14 13 4 4 4 missiles 66 76 40 100 Aircraft B-2 20 Tu-95 (Bear) 60 ― Rafale 40 H-6K 100 B-52 46 Tu-160 (Blackjack) 16 Approx. 3,800 Approx. 4,350 (including 215 300 Approx. 280 Number of warheads Approx. 1,830 tactical nuclear warheads) Notes: 1. Data is based on “The Military Balance 2019,” the SIPRI Yearbook 2018, etc. 2. In March 2019, the United States released the following figures based on the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty between the United States and Russia as of March 1, 2019: the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for the United States was 1,365 and the delivery vehicles involved 656 missiles/aircraft; the number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads for Russia was 1,461 and the delivery vehicles involved 524 missiles/aircraft. However, according to the SIPRI database, as of January 2018, the number of deployed U.S. -

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement 『神道事典』巻末年表、英語版 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics Kokugakuin University 2016 Preface This book is a translation of the chronology that appended Shinto jiten, which was compiled and edited by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. That volume was first published in 1994, with a revised compact edition published in 1999. The main text of Shinto jiten is translated into English and publicly available in its entirety at the Kokugakuin University website as "The Encyclopedia of Shinto" (EOS). This English edition of the chronology is based on the one that appeared in the revised version of the Jiten. It is already available online, but it is also being published in book form in hopes of facilitating its use. The original Japanese-language chronology was produced by Inoue Nobutaka and Namiki Kazuko. The English translation was prepared by Carl Freire, with assistance from Kobori Keiko. Translation and publication of the chronology was carried out as part of the "Digital Museum Operation and Development for Educational Purposes" project of the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Organization for the Advancement of Research and Development, Kokugakuin University. I hope it helps to advance the pursuit of Shinto research throughout the world. Inoue Nobutaka Project Director January 2016 ***** Translated from the Japanese original Shinto jiten, shukusatsuban. (General Editor: Inoue Nobutaka; Tokyo: Kōbundō, 1999) English Version Copyright (c) 2016 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. All rights reserved. Published by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University, 4-10-28 Higashi, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, Japan. -

Imagining Japan in Moscow and Sakhalin, and Imagining Russia in Tokyo and Hokkaido : Contrasting Identities and Title Images of Other in the Center and Periphery

Imagining Japan in Moscow and Sakhalin, and Imagining Russia in Tokyo and Hokkaido : Contrasting identities and Title images of Other in the center and periphery. Author(s) BUNTILOV, GEORGY Citation 北海道大学. 博士(教育学) 甲第13626号 Issue Date 2019-03-25 DOI 10.14943/doctoral.k13626 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/74661 Type theses (doctoral) File Information Georgy_Buntilov.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Doctoral Thesis Imagining Japan in Moscow and Sakhalin, and Imagining Russia in Tokyo and Hokkaido: Contrasting identities and images of Other in the center and periphery. モスクワ及びサハリンから見た日本と東京及び北海道 から見たロシア: 中心と周辺地域における「他者」に対する日本及びロ シアのアイデンティティとイメージの対比。 BUNTILOV GEORGY Department of Multicultural Studies Graduate School of Education Hokkaido University February 25, 2018 Abstract This thesis is a comparative analysis of newspaper articles that discusses two sets of images: images of Japan as seen in Russian federal and Sakhalin newspapers, and images of Russia as seen in Japanese national newspapers and Hokkaidō Shimbun. The project employs qualitative and quantitative content analysis to investigate imagery associated with Russia and Japan in printed media, as well as discourses on national identity in Russia and Japan. This research approaches Russo-Japanese relations from two angles: border studies through analysis of media in Hokkaido and Sakhalin, and the center–periphery paradigm through analysis of national and federal media. Using an identity model based on the phenomenological concepts of Self and Other, as well as the notion of antagonism, this research analyzes national identity discourses and images of the antagonized Other-nation in the center and periphery on each side of the border. -

Japan Ground Self-Defense Force

JGSDF Japan Ground Self-Defense Force Home Page of JGSDF JSDF Official YouTube Channel https://www.mod.go.jp/gsdf/ Home Page of JSDF Recruitment JSDF Recruitment Call Center https://www.mod.go.jp/gsdf/jieikanbosyu/ Special Special Feature Ground Defense Capability to realize Feature Newly-establishment and 1 "Multi-domain Defense Force" 2 Reorganization in JGSDF Ground Defense Concept based on "National Defense Program Guidelines (NDPG) 2018" Establishment of new camp and vice-camp We establish a ground defense force that will realize "Multi-domain Defense Force" and strengthen deterrence In order to strengthen defense posture in the Southwest region, we newly established security forces and through troop deployment and constant maneuver. In the event of an emergency, we block and eliminate others at camps such as Camp Amami and Camp Miyakojima on March 26, 2019. We also established invasions by exerting the cross-domain capability. Vice-camp Sakibe (Sasebo City, Nagasaki Prefecture) and deployed a part of ARDB. NDPG 2018 "Multi-domain Defense Force" Land Defense Capability to realize“Multi-domain Defense Force” Ground Defense Concept Cross-domain / Maneuver & Deployment / Strengthening of Foundation Mobile Fighting Vehicle loaded onto a ship Type-03 medium-range surface-to-air missile deployed at Camp Amami Camp Amami *Image Strengthening capabilities in Cyber and EMS domains Establishment of cyber defense unit Establishment of EMS operations unit Strengthening of deterrence and response capabilities through sustained and persistent maneuver