A Retrospective Journal for the Theater in England Trip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Witold Rybczynski HOME 1 7

Intimacy and Privacy C hap t e r Two 1' And yet it is precisely in these Nordic, apparently gloomy surroundings that Stimrnung, the sense of intimacy, was first born. - MARIO PRAZ AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY OF INTERIOR DECORATION Consid", the room which Albrecht Durer illustrated in his famous engraving St. Jerome in His Study. The great Ren aissance artist followed the convention of his time and showed the early Christian scholar not in a fifth-century setting-nor in Bethlehem, where he really lived- but in a study whose furnishings were typical of Durer's Nuremberg at the begin ning of the sixteenth century. We see an old man bent over his writing in the corner of a room. Light enters through a large leaded-glass window in an arched opening. A low bench stands against the wall under the window. Some tasseled cushions have been placed on it; upholstered seating, in which the cushion was an integral part of the seat, did not appear until a hundred years later. The wooden table is a medieval design-the top is separate from the underframe, and by removing a couple of pegs the whole thing can be easily disassembled when not in use. A back-stool, the precursor of the side chair, is next to the table. The tabletop is bare except for a crucifix, an inkpot, and a writing stand, but personal possessions are in evidence else Albrecht DUrer, St. Jerome in His where. A pair of slippers has been pushed under the bench. 15 Study (1514) ,... Witold Rybczynski HOME 1 7 folios on the workplace, whether it is a writer's room or the cockpit of a The haphazard is not a sign of sloppiness-bookcases have not yet jumbo jet. -

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 10/13/2010 12:42 Pm

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 10/13/2010 12:42 pm WNCU 90.7 FM Format: Jazz North Carolina Central University (Raleigh - Durham, NC) This Period (TP) = 10/06/2010 to 10/12/2010 Last Period (TP) = 09/29/2010 to 10/05/2010 TP LP Artist Album Label Album TP LP +/- Rank Rank Year Plays Plays 1 24 Tom Rizzo Imaginary Numbers Origin 2010 11 4 7 2 1 The Marsalis Family Music Redeems Marsalis 2010 10 12 -2 2 288 The Clayton Brothers The New Song And Dance ArtistShare 2010 10 0 10 4 4 Freddy Cole Freddy Cole Sings Mr.B HighNote 2010 8 8 0 4 4 Conrad Herwig The Latin Side Of Herbie Half Note 2010 8 8 0 Hancock 4 10 Jim Rotondi 1000 Rainbows Posi-Tone 2010 8 7 1 4 10 James Moody Moody 4B IPO 2010 8 7 1 4 24 Mauricio De Souza Here. There... Pulsa 2010 8 4 4 4 288 Bobby Watson The Gates BBQ Suite Lafiya 2010 8 0 8 10 3 Tomas Janzon Experiences Changes 2010 7 9 -2 10 13 Stephen Anderson Nation Degeneration Summit 2010 7 6 1 10 24 Steve Turre Delicious & Delightful HighNote 2010 7 4 3 10 288 Mary Stallings Dream HighNote 2010 7 0 7 14 4 Larry Coryell Prime Picks HighNote 2010 6 8 -2 14 30 Chicago Afro Latin Jazz Blueprints Chicago Sessions 2010 6 3 3 Ensemble 16 4 Nobuki Takamen Live: At The Iridium Summit 2010 5 8 -3 16 13 Royce Campbell Trio What Is This Thing Called? Philology 2010 5 6 -1 16 13 Regina Carter Reverse Thread E1 2010 5 6 -1 16 17 Chris Massey Vibrainium Self-Released 2010 5 5 0 20 2 Kenny Burrell Be Yourself HighNote 2010 4 11 -7 20 4 Danilo Perez Providencia Mack Avenue 2010 4 8 -4 20 4 Curtis -

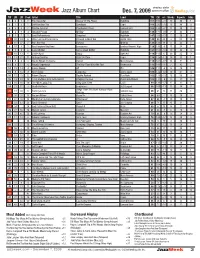

Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Dec

airplay data JazzWeek Jazz Album Chart Dec. 7, 2009 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW +/- Weeks Reports Adds 1 4 1 1 Eric Alexander Revival Of The Fittest HighNote 167 190 -23 10 46 1 2 1 3 1 Jeff Hamilton Trio Symbiosis Capri 166 236 -70 10 40 0 3 3 4 2 Poncho Sanchez Psychedelic Blues Concord Jazz 163 195 -32 11 40 0 4 6 7 4 Houston Person Mellow HighNote 149 171 -22 7 42 1 5 2 2 1 Joey DeFrancesco Snapshot HighNote 147 220 -73 7 50 2 6 23 39 6 Oliver Jones & Hank Jones Pleased To Meet You Justin Time 144 99 45 4 52 10 7 16 27 7 Roni Ben-Hur Fortuna Motema 136 120 16 4 42 2 8 10 4 1 Roy Hargrove Big Band Emergence EmArcy/Groovin’ High 128 136 -8 15 34 1 9 7 8 6 Cedar Walton Voices Deep Within HighNote 121 153 -32 10 44 0 10 18 12 1 Jackie Ryan Doozy Open Art 119 113 6 20 35 0 11 13 21 11 Graham Dechter Right On Time Capri 116 128 -12 10 33 1 12 5 6 3 Gerald Wilson Orchestra Detroit Mack Avenue 114 181 -67 13 41 1 13 8 11 8 Angela Hagenbach The Way They Make Me Feel Resonance 113 148 -35 7 42 2 14 19 14 4 James Moody 4A IPO 105 111 -6 14 34 1 15 9 15 9 Steve Davis Eloquence Jazz Legacy 104 146 -42 10 41 0 16 15 29 5 Robert Glasper Double Booked Blue Note 103 123 -20 15 56 0 16 19 32 16 Terell Stafford, Dick Oatts Quintet Bridging The Gap Planet Arts/Blujazz 103 111 -8 5 27 0 18 10 10 10 The Mike Longo Trio Sting Like A Bee C.A.P. -

Reading Abbey Revealed Conservation Plan August 2015

Reading Abbey Revealed Conservation Plan August 2015 Rev A First Draft Issue P1 03/08/2015 Rev B Stage D 10/08/2015 Prepared by: Historic Buildings Team, HCC Property Services, Three Minsters House, 76 High Street, Winchester, SO23 8UL On behalf of: Reading Borough Council Civic Offices, Bridge Street, Reading RG1 2LU Conservation Plan – Reading Abbey Revealed Contents Page Historical Timeline ………………………………………………………………………………. 1 1.0 Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………… 2 2.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 3.0 Understanding the Heritage 3.1 – Heritage Description ……………………………………………………………………… 5 3.2 – History ……………………………………………………………………………………… 5 3.3 – Local Context ……………………………………………………………………………… 19 3.4 – Wider Heritage Context ………………………………………………………………….. 20 3.5 – Current Management of Heritage ………………………………………………………. 20 4.0 Statement of Significance 4.1 – Evidential Value ………………………………………………………………………….. 21 4.2 – Historical Value …………………………………………………………………………... 21 4.3 – Aesthetic Value …………………………………………………………………………… 21 4.4 – Communal Value …………………………………………………………………………. 22 4.5 - Summary of Significance ………………………………………………………………... 24 5.0 Risks to Heritage and Opportunities 5.1 – Risks ………………………………………………………………………………………. 26 5.2 – Opportunities ……………………………………………………………………………… 36 6.0 Policies 6.1 – Conservation, maintenance and climate change …………………………………….. 38 6.2 – Access and Interpretation ……………………………………………………………….. 39 6.3 – Income Generation ………………………………………………………………………. 40 7.0 Adoption and Review 7.1 – General Approach -

Healing Relationships

HEALING RELATIONSHIPS This book is dedicated to the loving memory of my Mother, Oma Moseley, who taught me the power of words & my Daddy, Fred Moseley, who taught me how to play with words HEALING RELATIONSHIPS A Preaching Model DAN MOSELEY Copyright ©2009 by Dan Moseley. All rights reserved. For permission to reuse content, please contact Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, www.copyright.com. Bible quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Those quotations marked RSV are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1952, [2nd edition, 1971] by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover image: FotoSearch Cover and interior design: Elizabeth Wright Visit Chalice Press on the World Wide Web at www.chalicepress.com 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moseley, Dan. Healing relationships : a preaching model / by Dan Moseley. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-8272-1455-2 1. Preaching. 2. Interpersonal relations--Religious aspects—Christianity—Sermons. 3. Sermons, American. I. Title. BV4222.M67 2008 251—dc22 2008026811 Printed in United States of America Contents Prelude vii 1. The Reluctant Pilgrim Sermon 1 Leaving Home (Ex. 3:1–12) 2. -

Cultural & Heritagetourism

Cultural & HeritageTourism a Handbook for Community Champions A publication of: The Federal-Provincial-Territorial Ministers’ Table on Culture and Heritage (FPT) Table of Contents The views presented here reflect the Acknowledgements 2 Section B – Planning for Cultural/Heritage Tourism 32 opinions of the authors, and do not How to Use this Handbook 3 5. Plan for a Community-Based Cultural/Heritage Tourism Destination ������������������������������������������������ 32 necessarily represent the official posi- 5�1 Understand the Planning Process ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 32 tion of the Provinces and Territories Developed for Community “Champions” ��������������������������������������� 3 which supported the project: Handbook Organization ����������������������������������������������������� 3 5�2 Get Ready for Visitors ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 33 Showcase Studies ���������������������������������������������������������� 4 Alberta Showcase: Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump and the Fort Museum of the NWMP Develop Aboriginal Partnerships ��� 34 Learn More… �������������������������������������������������������������� 4 5�3 Assess Your Potential (Baseline Surveys and Inventory) ������������������������������������������������������������� 37 6. Prepare Your People �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 41 Section A – Why Cultural/Heritage Tourism is Important 5 6�1 Welcome -

Æ‚‰É”·ȯLj¾é “ Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ

æ‚‰é” Â·è¯ çˆ¾é “ 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & æ—¶é— ´è¡¨) Spectrum https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spectrum-7575264/songs The Electric Boogaloo Song https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-electric-boogaloo-song-7731707/songs Soundscapes https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/soundscapes-19896095/songs Breakthrough! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/breakthrough%21-4959667/songs Beyond Mobius https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/beyond-mobius-19873379/songs The Pentagon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-pentagon-17061976/songs Composer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/composer-19879540/songs Roots https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/roots-19895558/songs Cedar! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/cedar%21-5056554/songs The Bouncer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-bouncer-19873760/songs Animation https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/animation-19872363/songs Duo https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/duo-30603418/songs The Maestro https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-maestro-19894142/songs Voices Deep Within https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/voices-deep-within-19898170/songs Midnight Waltz https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/midnight-waltz-19894330/songs One Flight Down https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/one-flight-down-20813825/songs Manhattan Afternoon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/manhattan-afternoon-19894199/songs Soul Cycle https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/soul-cycle-7564199/songs -

Transactions Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club

TRANSACTIONS OF THE WOOLHOPE NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB HEREFORDSHIRE "HOPE ON" "HOPE EVER" ESTABLISHED 1851 VOLUME XLV 1986 PART II TRANSACTIONS OF THE WOOLHOPE NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB HEREFORDSHIRE "HOPE ON" "HOPE EVER" ESTABLISHED 1851 VOLUME XLV 1986 PART II TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Proceedings, 1986 - 335 Hereford in the 1850s, by Clarence E. Attfield - - 347 A Roman Forger at Kenchester, by R. Shoesmith - 371 Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club 1986 The Fief of Alfred of Marlborough in Herefordshire in 1086 and its All contributions to The Woolhope Transactions are COPYRIGHT. None of them Descent in the Norman Period, by Bruce Coplestone-Crow - - 376 may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the writers. Applications to reproduce contributions, in whole or St. Ethelbert's Hospital, Hereford: Its architecture and setting, in part, should be addressed in the first instance, to the editor whose address is given - 415 in the LIST OF OFFICERS. by David Whitehead The Annunciation and the Lily Crucifixion, by G. W. Kemp - 426 Thomas Charlton, Bishop of Hereford, 1327-1344, by G. W. Hannah - - 442 The Seventeenth Century Iron Forge at Carey Mill, by Elizabeth Taylor - 450 Herefordshire Apothecaries' Tokens and their Issuers, by the late T. D. Whittet - 469 The political organisation of Hereford, 1693-1736, by E. J. Morris 477 Population Movements in 19th Century Herefordshire, by Joan E. Grundy - 488 Two Celtic Heads, by Jean O'Donnell - - 501 Further Addenda to Lepidoptera in Hereford City (1973-82), by B. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

Austro-American Reflections: Making the Writings of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible To

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2012-12-12 Austro-American Reflections: Making the ritingsW of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible to English-Speaking Audiences Stephen Andrew Simon Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the German Language and Literature Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Simon, Stephen Andrew, "Austro-American Reflections: Making the ritingsW of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible to English-Speaking Audiences" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 3543. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3543 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Austro-American Reflections: Making the Writings of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible to English-Speaking Audiences Stephen A. Simon A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Robert McFarland, Chair Michelle James Cindy Brewer Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages Brigham Young University December 2012 Copyright © 2012 Stephen A. Simon All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Austro-American Reflections: Making the Writings of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible to English-Speaking Audiences Stephen A. Simon Department of German Studies and Slavic Languages, BYU Master of Arts Ann Tizia Leitich wrote about America to a Viennese audience as a foreign correspondent with the unique and personal perspective of an immigrant to the United States. Leitich differentiates herself from other Europeans who reported on America in her day by telling of the life of the average working American. -

Tourisme Outaouais

OFFICIAL TOURIST GUIDE 2018-2019 Outaouais LES CHEMINS D’EAU THE OUTAOUAIS’ TOURIST ROUTE Follow the canoeist on the blue signs! You will learn the history of the Great River and the founding people who adopted it. Reach the heart of the Outaouais with its Chemins d’eau. Mansfield-et-Pontefract > Mont-Tremblant La Pêche (Wakefield) Montebello Montréal > Gatineau Ottawa > cheminsdeau.ca contents 24 6 Travel Tools regional overview 155 Map 8 Can't-miss Experiences 18 Profile of the Region 58 top things to do 42 Regional Events 48 Culture & Heritage 64 Nature & Outdoor Activities 88 Winter Fun 96 Hunting & Fishing 101 Additional Activities 97 112 Regional Flavours accommodation and places to eat 121 Places to Eat 131 Accommodation 139 useful informations 146 General Information 148 Travelling in Quebec 150 Index 153 Legend of Symbols regional overview 155 Map TRAVEL TOOLS 8 Can't-miss Experiences 18 Profile of the Region Bring the Outaouais with you! 20 Gatineau 21 Ottawa 22 Petite-Nation La Lièvre 26 Vallée-de-la-Gatineau 30 Pontiac 34 Collines-de-l’Outaouais Visit our website suggestions for tours organized by theme and activity, and also discover our blog and other social media. 11 Website: outaouaistourism.com This guide and the enclosed pamphlets can also be downloaded in PDF from our website. Hard copies of the various brochures are also available in accredited tourism Welcome Centres in the Outaouais region (see p. 146). 14 16 Share your memories Get live updates @outaouaistourism from Outaouais! using our hashtag #OutaouaisFun @outaouais -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microShn master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from aiy type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 3 0 0 North Z eeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.'761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Nmnber 9411906 Disembodied and re-embodied voices: The figure of Echo in American Gothic texts Beutel, Katherine Piller, Ph.D.