Austro-American Reflections: Making the Writings of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Arrival of the First Film Sound Systems in Spain (1895-1929)

Journal of Sound, Silence, Image and Technology 27 Issue 1 | December 2018 | 27-41 ISSN 2604-451X The arrival of the first film sound systems in Spain (1895-1929) Lidia López Gómez Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona [email protected] Date received: 10-01-2018 Date of acceptance: 31-03-2018 PALABRAS CLAVE: CINE MUDO | SONIDO | RecepcIÓN | KINETÓFONO | CHRONOPHONE | PHONOFILM KEY WORDS: SILENT FILM | SOUND | RecepTION | KINETOPHONE | CHRONOPHONE | PHONOFILM Journal of Sound, Silence, Image and Technology | Issue 1 | December 2018. 28 The arrival of the first film sound systems in spain (1895-1929) ABSTracT During the final decade of the 19th century, inventors such as Thomas A. Edison and the Lumière brothers worked assiduously to find a way to preserve and reproduce sound and images. The numerous inventions conceived in this period such as the Kinetophone, the Vitascope and the Cinematograph are testament to this and are nowadays consid- ered the forerunners of cinema. Most of these new technologies were presented at public screenings which generated a high level of interest. They attracted people from all social classes, who packed out the halls, theatres and hotels where they were held. This paper presents a review of the newspa- per and magazine articles published in Spain at the turn of the century in order to study the social reception of the first film equip- ment in the country, as well as to understand the role of music in relation to the images at these events and how the first film systems dealt with sound. Journal of Sound, Silence, Image and Technology | Issue 1 | December 2018. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 10/13/2010 12:42 Pm

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 10/13/2010 12:42 pm WNCU 90.7 FM Format: Jazz North Carolina Central University (Raleigh - Durham, NC) This Period (TP) = 10/06/2010 to 10/12/2010 Last Period (TP) = 09/29/2010 to 10/05/2010 TP LP Artist Album Label Album TP LP +/- Rank Rank Year Plays Plays 1 24 Tom Rizzo Imaginary Numbers Origin 2010 11 4 7 2 1 The Marsalis Family Music Redeems Marsalis 2010 10 12 -2 2 288 The Clayton Brothers The New Song And Dance ArtistShare 2010 10 0 10 4 4 Freddy Cole Freddy Cole Sings Mr.B HighNote 2010 8 8 0 4 4 Conrad Herwig The Latin Side Of Herbie Half Note 2010 8 8 0 Hancock 4 10 Jim Rotondi 1000 Rainbows Posi-Tone 2010 8 7 1 4 10 James Moody Moody 4B IPO 2010 8 7 1 4 24 Mauricio De Souza Here. There... Pulsa 2010 8 4 4 4 288 Bobby Watson The Gates BBQ Suite Lafiya 2010 8 0 8 10 3 Tomas Janzon Experiences Changes 2010 7 9 -2 10 13 Stephen Anderson Nation Degeneration Summit 2010 7 6 1 10 24 Steve Turre Delicious & Delightful HighNote 2010 7 4 3 10 288 Mary Stallings Dream HighNote 2010 7 0 7 14 4 Larry Coryell Prime Picks HighNote 2010 6 8 -2 14 30 Chicago Afro Latin Jazz Blueprints Chicago Sessions 2010 6 3 3 Ensemble 16 4 Nobuki Takamen Live: At The Iridium Summit 2010 5 8 -3 16 13 Royce Campbell Trio What Is This Thing Called? Philology 2010 5 6 -1 16 13 Regina Carter Reverse Thread E1 2010 5 6 -1 16 17 Chris Massey Vibrainium Self-Released 2010 5 5 0 20 2 Kenny Burrell Be Yourself HighNote 2010 4 11 -7 20 4 Danilo Perez Providencia Mack Avenue 2010 4 8 -4 20 4 Curtis -

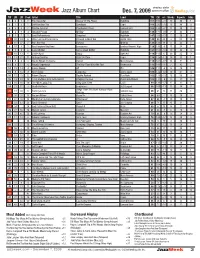

Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Dec

airplay data JazzWeek Jazz Album Chart Dec. 7, 2009 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW +/- Weeks Reports Adds 1 4 1 1 Eric Alexander Revival Of The Fittest HighNote 167 190 -23 10 46 1 2 1 3 1 Jeff Hamilton Trio Symbiosis Capri 166 236 -70 10 40 0 3 3 4 2 Poncho Sanchez Psychedelic Blues Concord Jazz 163 195 -32 11 40 0 4 6 7 4 Houston Person Mellow HighNote 149 171 -22 7 42 1 5 2 2 1 Joey DeFrancesco Snapshot HighNote 147 220 -73 7 50 2 6 23 39 6 Oliver Jones & Hank Jones Pleased To Meet You Justin Time 144 99 45 4 52 10 7 16 27 7 Roni Ben-Hur Fortuna Motema 136 120 16 4 42 2 8 10 4 1 Roy Hargrove Big Band Emergence EmArcy/Groovin’ High 128 136 -8 15 34 1 9 7 8 6 Cedar Walton Voices Deep Within HighNote 121 153 -32 10 44 0 10 18 12 1 Jackie Ryan Doozy Open Art 119 113 6 20 35 0 11 13 21 11 Graham Dechter Right On Time Capri 116 128 -12 10 33 1 12 5 6 3 Gerald Wilson Orchestra Detroit Mack Avenue 114 181 -67 13 41 1 13 8 11 8 Angela Hagenbach The Way They Make Me Feel Resonance 113 148 -35 7 42 2 14 19 14 4 James Moody 4A IPO 105 111 -6 14 34 1 15 9 15 9 Steve Davis Eloquence Jazz Legacy 104 146 -42 10 41 0 16 15 29 5 Robert Glasper Double Booked Blue Note 103 123 -20 15 56 0 16 19 32 16 Terell Stafford, Dick Oatts Quintet Bridging The Gap Planet Arts/Blujazz 103 111 -8 5 27 0 18 10 10 10 The Mike Longo Trio Sting Like A Bee C.A.P. -

Healing Relationships

HEALING RELATIONSHIPS This book is dedicated to the loving memory of my Mother, Oma Moseley, who taught me the power of words & my Daddy, Fred Moseley, who taught me how to play with words HEALING RELATIONSHIPS A Preaching Model DAN MOSELEY Copyright ©2009 by Dan Moseley. All rights reserved. For permission to reuse content, please contact Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, www.copyright.com. Bible quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Those quotations marked RSV are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1952, [2nd edition, 1971] by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover image: FotoSearch Cover and interior design: Elizabeth Wright Visit Chalice Press on the World Wide Web at www.chalicepress.com 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moseley, Dan. Healing relationships : a preaching model / by Dan Moseley. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-8272-1455-2 1. Preaching. 2. Interpersonal relations--Religious aspects—Christianity—Sermons. 3. Sermons, American. I. Title. BV4222.M67 2008 251—dc22 2008026811 Printed in United States of America Contents Prelude vii 1. The Reluctant Pilgrim Sermon 1 Leaving Home (Ex. 3:1–12) 2. -

The Allied Powers; the Central What Did Citizens Think the U.S

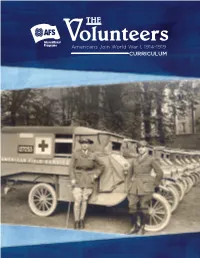

Connecting lives. Sharing cultures. Dear Educator, Welcome to The Volunteers: Americans Join World War I, 1914-1919 Curriculum! Please join us in celebrating the release of this unique and relevant curriculum about U.S. American volunteers in World War I and how volunteerism is a key component of global competence and active citizenship education today. These free, Common Core and UNESCO Global Learning-aligned secondary school lesson plans explore the motivations behind why people volunteer. They also examine character- istics of humanitarian organizations, and encourage young people to consider volunteering today. AFS Intercultural Programs created this curriculum in part to commemorate the 100 year history of AFS, founded in 1915 as a volunteer U.S. American ambulance corps serving alongside the French military during the period of U.S. neutrality. Today, AFS Intercultural Programs is a non-profit, intercultural learn- ing and student exchange organization dedicated to creating active global citizens in today’s world. The curriculum was created by AFS Intercultural Programs, together with a distinguished Curriculum Development Committee of historians, educators, and archivists. The lesson plans were developed in partnership with the National World War I Museum and Memorial and the curriculum specialists at Pri- mary Source, a non-profit resource center dedicated to advancing global education. We are honored to have received endorsement for the project from the United States World War I Centennial Commission. We would like to thank the AFS volunteers, staff, educators, and many others who have supported the development of this curriculum and whose daily work advances the AFS mission. We encourage sec- ondary school teachers around the world to adapt these lesson plans to fit their classroom needs- les- sons can be applied in many different national contexts. -

Presidential Documents

Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents Monday, September 29, 1997 Volume 33ÐNumber 39 Pages 1371±1429 1 VerDate 22-AUG-97 07:53 Oct 01, 1997 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 1249 Sfmt 1249 W:\DISC\P39SE4.000 p39se4 Contents Addresses and Remarks Communications to CongressÐContinued See also Meetings With Foreign Leaders Future free trade area negotiations, letter Arkansas, Little Rock transmitting reportÐ1423 Congressional Medal of Honor Society India-U.S. extradition treaty and receptionÐ1419 documentation, message transmittingÐ1401 40th anniversary of the desegregation of Iraq, letter reportingÐ1397 Central High SchoolÐ1416 Ireland-U.S. taxation convention and protocol, California message transmittingÐ1414 San Carlos, roundtable discussion at the UNITA, message transmitting noticeÐ1414 San Carlos Charter Learning CenterÐ 1372 Communications to Federal Agencies San Francisco Contributions to the International Fund for Democratic National Committee Ireland, memorandumÐ1396 dinnerÐ1382 Funding for the African Crisis Response Democratic National Committee luncheonÐ1376 Initiative, memorandumÐ1397 Saxophone Club receptionÐ1378 Interviews With the News Media New York City, United Nations Exchange with reporters at the United LuncheonÐ1395 Nations in New York CityÐ1395 52d Session of the General AssemblyÐ1386 Interview on the Tom Joyner Morning Show Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh in Little RockÐ1423 AFL±CIO conventionÐ1401 Democratic National Committee luncheonÐ1408 Letters and Messages Radio addressÐ1371 50th anniversary of the National Security Council, messageÐ1396 Communications to Congress Meetings With Foreign Leaders Angola, message reportingÐ1414 Russia, Foreign Minister PrimakovÐ1395 Canada-U.S. taxation convention protocol, message transmittingÐ1400 Notices Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty and Continuation of Emergency With Respect to documentation, message transmittingÐ1390 UNITAÐ1413 (Continued on the inside of the back cover.) Editor's Note: The President was in Little Rock, AR, on September 26, the closing date of this issue. -

Medien & Zeit 4/1987.Pdf

Forum für historische Kommunikationsforschung ZEIT Spiitc Aufarbeitung der Rolle der Zeitungswissenschaft 1933— 1945 „Das Große Tabu“ Österreichs Umgang mit seiner Vergangenheit Faszination Drittes Reich Kulturmetropole Salzburg 1938 was mein ... wirkliches Leben ist“ Über Alfred Schütz Anmerkungen zu den Österreichischen Film-Tagen 1987 4/87 Jahrgang 2 Mcdieninhaber und Herausgeber: Verein „Arbeitskreis für historische Kommunikationsforschung (AHK)“, 1014 Wien, Postfach 208; Vorstand des AHK: DDr. Oliver Rathkolb (Obmann), Dr. Hannes Haas (Obmann-Stv.), Dr. Roman Hummel (Obmann-Stv.), Dr. Wolfgang Duchkowitsch (Geschäftsführer), Dr. Peter Malina (Geschäfts- führer-Stv.), Margit Suppan (Kassierin), Dr. Theodor Venus (Kassier-Stv.), Margit Steiger (Schriftführerin), Dr. Fritz Hausjell (Schriftführer-Stv.) Korrespondenten: Dr. Hans Bohrmann (Dortmund), Dr. Robert Knight (London), Dr. Arnulf Kutsch (Münster), Dr. Edmund Schulz (Leipzig) Redaktion: Vorstand des AHK; redaktionelle Leitung dieses Heftes: DDr. Oliver Rathkolb, Dr. Theodor Venus Hersteller: Satz und Layout: Ulrike Horak Druckvorlage: Fa. Adolf Holzhausens Nfg., 1070 Wien, Kandlgasse 19—21 Druck: HTU, Wirtschaftsbetriebe Ges. m. b. H., 1040 Gußhausstraße 27—29 Erscheinungsweise: MEDIEN & ZEIT erscheint vierteljährlich Bezugsbedingungen: Jahresabonnement: öS 150.— (Inland), öS 150.— + Porto (Ausland) Studentenjahresabonnement: öS 110.— (mit Inskriptionsnachweis) Einzelheft: öS 45.— Bestellungen an MEDIEN & ZEIT, 1014 Wien, Postfach 208 Bankverbindungen: Creditanstalt-Bankverein (CA-BV), Konto Nr. 0123-01263/00, BLZ 11.000 Österreichische Länderbank, Konto Nr. 102-113-378/00, BLZ 12.000 Österreichische Postsparkasse (PSK), Konto Nr. 7510.438 Gefördert vom Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft und Forschung in Wien ISSN 0259—7446 Medien & Zeit 4/87 Inhalt Editorial Die späte Einsicht. Ein Essay über die fehlende Bereits 1987 wirft der ,März 1988" seine dunklen Aufarbeitung der Rolle der Zeitungswissenschaft Schatten auf Österreich, und die politisch aktive zwischen 1933 und 1945. -

Conrad Von Hötzendorf and the “Smoking Gun”: a Biographical Examination of Responsibility and Traditions of Violence Against Civilians in the Habsburg Army 55

1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) Samuel R. Williamson, Jr. (Guest Editor) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 23 uno press innsbruck university press Copyright © 2014 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Design by Allison Reu Cover photo: “In enemy position on the Piave levy” (Italy), June 18, 1918 WK1/ALB079/23142, Photo Kriegsvermessung 5, K.u.k. Kriegspressequartier, Lichtbildstelle Vienna Cover photo used with permission from the Austrian National Library – Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Vienna Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608010264 ISBN: 9783902936356 uno press Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Ferdinand Karlhofer, Universität Innsbruck Assistant Editor Markus Habermann -

Yankees Who Fought for the Maple Leaf: a History of the American Citizens

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 12-1-1997 Yankees who fought for the maple leaf: A history of the American citizens who enlisted voluntarily and served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force before the United States of America entered the First World War, 1914-1917 T J. Harris University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Harris, T J., "Yankees who fought for the maple leaf: A history of the American citizens who enlisted voluntarily and served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force before the United States of America entered the First World War, 1914-1917" (1997). Student Work. 364. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/364 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Yankees Who Fought For The Maple Leaf’ A History of the American Citizens Who Enlisted Voluntarily and Served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force Before the United States of America Entered the First World War, 1914-1917. A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts University of Nebraska at Omaha by T. J. Harris December 1997 UMI Number: EP73002 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Sound: Eine Arbeitsbibliographie 2003

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Hans Jürgen Wulff Sound: Eine Arbeitsbibliographie 2003 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12795 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Wulff, Hans Jürgen: Sound: Eine Arbeitsbibliographie. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, Institut für Germanistik 2003 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 17). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12795. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0017_03.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft / Kiel: Berichte und Papiere 17, 1999: Sound. ISSN 1615-7060. Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Hans J. Wulff. Letzte Änderung: 21.9.2008. URL der Hamburger Ausgabe: .http://www1.uni-hamburg.de/Medien/berichte/arbeiten/0017_03.pdf Sound: Eine Arbeitsbibliographie Hans J. Wulff Stille und Schweigen. Themenheft der: Navigatio- Akemann, Walter (1931) Tontechnik und Anwen- nen: Siegener Beiträge zur Medien- und Kulturwis- dung des Tonkoffergerätes. In: Kinotechnik v. 5.12. senschaft 3,2, 2003. 1931, pp. 444ff. Film- & TV-Kameramann 57,9, Sept. 2008, pp. 60- Aldred, John (1978) Manual of sound recording. 85: „Originalton“. 3rd ed. :Fountain Press/Argus Books 1978, 372 pp. Aldred, John (1981) Fifty years of sound. American Cinematographer, Sept. 1981, pp. 888-889, 892- Abbott, George (1929) The big noise: An unfanati- 897. -

Suzanne Marwille – Women Film Pioneers Project

5/18/2020 Suzanne Marwille – Women Film Pioneers Project Suzanne Marwille Also Known As: Marta Schölerová Lived: July 11, 1895 - January 14, 1962 Worked as: film actress, screenwriter Worked In: Czechoslovakia, Germany by Martin Šrajer To date, there are only about ten women screenwriters known to have worked in the Czech silent film industry. Some of them are more famous today as actresses, directors, or entrepreneurs. This is certainly true of Suzanne Marwille, who is considered to be the first Czech female film star. Less known is the fact that she also had a talent for writing, as well as dramaturgy and casting. Between 1918 and 1937, she appeared in at least forty films and wrote the screenplays for eight of them. Born Marta Schölerová in Prague on July 11, 1895, she was the second of four daughters of postal clerk Emerich Schöler and his wife Bedřiška Peceltová (née Nováková). There is a scarcity of information about Marta’s early life, but we know that in June 1914, at the age of eighteen, she married Gustav Schullenbauer. According to the marriage registry held at the Prague City Archives, he was then a twenty-year-old volunteer soldier one year into his service in the Austrian-Hungarian army (Matrika oddaných 74). Four months later, their daughter—the future actress and dancer Marta Fričová—was born. The marriage lasted ten years, which coincided with the peak years of Marwille’s career. As was common at the time, Marwille was discovered in the theater, although probably not as a stage actress. While many unknowns still remain about this occasion, it was reported that film industry professionals first saw her sitting in the audience of a Viennese theater at the end of World War I (“Suzanne Marwille” 2).