Tributaries 2015 Tributaries T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASPSU President Approves SFC 2012–13 Budget Proposal

INDEX Nationals or bust NEWS............................2 FREE ARTS...............................6 The Vanguard is published every Senior Sean MacKelvie moves OPINION.........................11 Tuesday and Thursday SPORTS..........................14 on to nationals in javelin SPORTS pagE 14 PSUVANGUARD.COM PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHED SINCE 1946 PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHED SINCE 1946 THURSDAY, MAY 31, 2012 • VOL. 66 NO. 59 Strategies for a ASPSU president approves global university SFC 2012–13 budget proposal PSU releases internationalization of the local re- new vision for gion, leveraging global engagements and mobilizing international alumni. internationalization The strategy was created by the In- ternational Council, a group of more KATRINA PETrovICH VANGUARD STAFF than 20 faculty, staff and student rep- resentatives from all of PSU’s differ- Portland State has a new vision for ent academic colleges and institutes. global education. The university recent- According to the council’s chair, ly released the Strategy for Comprehen- Professor Vivek Shandas, this inter- sive Internationalization, a report that nationalization strategy was two and establishes an eight-year framework for a half years in the making. how PSU plans to become a more glob- “This strategy tries to help coor- ally focused institution. dinate, integrate and then ultimately “The creation of this strategy follows disseminate all the internationaliza- from a recognition that we live in a global tion efforts happening on campus,” society now. All of the things that a uni- Shandas said. versity does need to fit into that context,” He claimed that, unlike a lot of uni- explained Provost and Vice President for versities, PSU has a multitude of in- Academic Affairs Roy Koch. -

TTTC Full Text

The Things They Carried By Tim O’Brien The Things They Carried First Lieutenant Jimmy Cross carried letters from a girl named Martha, a junior at Mount Sebastian College in New Jersey. They were not love letters, but Lieutenant Cross was hoping, so he kept them folded in plastic at the bottom of his rucksack. In the late afternoon, after a day's march, he would dig his foxhole, wash his hands under a canteen, unwrap the letters, hold them with the tips of his fingers, and spend the last hour of light pretending. He would imagine romantic camping trips into the White Mountains in New Hampshire. He would sometimes taste the envelope flaps, knowing her tongue had been there. More than anything, he wanted Martha to love him as he loved her, but the letters were mostly chatty, elusive on the matter of love. She was a virgin, he was almost sure. She was an English major at Mount Sebastian, and she wrote beautifully about her professors and roommates and midterm exams, about her respect for Chaucer and her great affection for Virginia Woolf. She often quoted lines of poetry; she never mentioned the war, except to say, Jimmy, take care of yourself. The letters weighed 10 ounces. They were signed Love, Martha, but Lieutenant Cross understood that Love was only a way of signing and did not mean what he sometimes pretended it meant. At dusk, he would carefully return the letters to his rucksack. Slowly, a bit distracted, he would get up and move among his men, checking the perimeter, then at full dark he would return to his hole and watch the night and wonder if Martha was a virgin. -

Episode 308: JOHNNYSWIM That Sounds Fun with Annie F. Downs

Episode 308: JOHNNYSWIM That Sounds Fun with Annie F. Downs [00:00:00] <Music> Annie: Hi friends, welcome to another episode of That Sounds Fun. I'm your host Annie F. Downs, I'm really happy to be here with you today. We've got a great show in store, one y'all have been requesting for always. So I'm thrilled about today's show. And before we get started, I want to tell you about one of our incredible partners, CRU. It probably goes without saying, but here I am saying it anyways, reading the Bible is so important to me. If you've been following me through 2021, you know, I've been doing the Bible in a Year, and I'm always blown away by the new things I learn, even in passages I feel like I've read 100 times. But imagine for a second that you couldn't get a Bible, like you couldn't afford one or couldn't just hop on Amazon and have one sent to your house. Take it one step further, and imagine that you aren't even allowed to have one. Honestly, sometimes we forget that there are so many people all around the world, who simply can't get a Bible. And that's why we're thrilled to partner with Cru. Cru is one of the largest evangelical organizations in the world, with over 25,000 missionaries in almost every country. Cru has given Bibles to people in their own heart language, and sharing the hope of Jesus all around the globe. -

Strangers on a Train

Strangers on a Train PATRICIA HIGHSMITH Level 4 Retold by Michael Nation Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN 0 582 41812 7 Strangers on a Train copyright 1950 by Patricia Highsmith This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd. 1998 New edition first published 1999 Third impression 2000 Text copyright © Michael Nation 1995 Illustrations copyright © Ian Andrew 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk Set in ll/14pt Monotype Bembo Printed in Spain by Mateu Cromo, S.A. Pinto (Madrid) All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Limited in association with Penguin Books Ltd., both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Plc For a complete list of the tides available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Education office or to: Marketing Department, Penguin Longman Publishing, 5 Bentinck Street, London W1M 5RN. Contents page Introduction iv Chapter 1 The First Meeting 1 Chapter 2 A Difficult Day with Miriam 7 Chapter 3 Good News for Guy 10 Chapter 4 Bruno Gets Ready -

Download Song List

song list t 01282 772646 m 07790 584 922 e [email protected] gavinyoung.co.uk Song Title Artist Genre Moonriver Andy Williams / Buble Big Band/swing Minnie The Moocher Cab Galloway Big Band/swing Dream Dean Martin Big Band/swing Little Old Wine Drinker Me Dean Martin Big Band/swing Kick In The Head Dean Martin Buble Big Band/swing Volare Dean Martin/buble Big Band/swing Come Fly With Me Frank Sinatra Big Band/swing A Foggy Day Michael Buble Big Band/swing A Song For You Michael Buble Big Band/swing All I Do Is Dream Of You Michael Buble Big Band/swing All Of Me Michael Buble Big Band/swing Alway On My Mind Michael Buble Big Band/swing At This Moment Michael Buble Big Band/swing Baby You've Got What It Takes Michael Buble Big Band/swing Call Me Irresponsible Michael Buble Big Band/swing Cant Buy Me Love Michael Buble Big Band/swing Cant Take That Away From Me Michael Buble Big Band/swing Chicago Michael Buble Big Band/swing Close Your Eyes Michael Buble Big Band/swing Coming Home Baby Michael Buble Big Band/swing Crazy Little Thing Called Love Michael Buble Big Band/swing Crazy Love Michael Buble Big Band/swing Cry Me A River Michael Buble Big Band/swing Dream A Little Dream Michael Buble Big Band/swing End Of May Michael Buble Big Band/swing Everything Michael Buble Big Band/swing Feeling Good Michael Buble Big Band/swing Fly Me To The Moon Michael Buble Big Band/swing For Once In My Life Michael Buble Big Band/swing Georgia Michael Buble Big Band/swing Have I Told You Lately That I Love You Michael Buble Big Band/swing Haven’t Met -

Partyman by Title

Partyman by Title #1 Crush (SCK) (Musical) Sound Of Music - Garbage - (Musical) Sound Of Music (SF) (I Called Her) Tennessee (PH) (Parody) Unknown (Doo Wop) - Tim Dugger - That Thing (UKN) 007 (Shanty Town) (MRE) Alan Jackson (Who Says) You - Can't Have It All (CB) Desmond Decker & The Aces - Blue Oyster Cult (Don't Fear) The - '03 Bonnie & Clyde (MM) Reaper (DK) Jay-Z & Beyonce - Bon Jovi (You Want To) Make A - '03 Bonnie And Clyde (THM) Memory (THM) Jay-Z Ft. Beyonce Knowles - Bryan Adams (Everything I Do) I - 1 2 3 (TZ) Do It For You (SCK) (Spanish) El Simbolo - Carpenters (They Long To Be) - 1 Thing (THM) Close To You (DK) Amerie - Celine Dion (If There Was) Any - Other Way (SCK) 1, 2 Step (SCK) Cher (This Is) A Song For The - Ciara & Missy Elliott - Lonely (THM) 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) (CB) Clarence 'Frogman' Henry (I - Plain White T's - Don't Know Why) But I Do (MM) 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New (SF) Cutting Crew (I Just) Died In - Coolio - Your Arms (SCK) 1,000 Faces (CB) Dierks Bentley -I Hold On (Ask) - Randy Montana - Dolly Parton- Together You And I - (CB) 1+1 (CB) Elvis Presley (Now & Then) - Beyonce' - There's A Fool Such As I (SF) 10 Days Late (SCK) Elvis Presley (You're So Square) - Third Eye Blind - Baby I Don't Care (SCK) 100 Kilos De Barro (TZ) Gloriana (Kissed You) Good - (Spanish) Enrique Guzman - Night (PH) 100 Years (THM) Human League (Keep Feeling) - Five For Fighting - Fascination (SCK) 100% Pure Love (NT) Johnny Cash (Ghost) Riders In - The Sky (SCK) Crystal Waters - K.D. -

Jazz Quartess Songlist Pop, Motown & Blues

JAZZ QUARTESS SONGLIST POP, MOTOWN & BLUES One Hundred Years A Thousand Years Overjoyed Ain't No Mountain High Enough Runaround Ain’t That Peculiar Same Old Song Ain’t Too Proud To Beg Sexual Healing B.B. King Medley Signed, Sealed, Delivered Boogie On Reggae Woman Soul Man Build Me Up Buttercup Stop In The Name Of Love Chasing Cars Stormy Monday Clocks Summer In The City Could It Be I’m Fallin’ In Love? Superstition Cruisin’ Sweet Home Chicago Dancing In The Streets Tears Of A Clown Everlasting Love (This Will Be) Time After Time Get Ready Saturday in the Park Gimme One Reason Signed, Sealed, Delivered Green Onions The Scientist Groovin' Up On The Roof Heard It Through The Grapevine Under The Boardwalk Hey, Bartender The Way You Do The Things You Do Hold On, I'm Coming Viva La Vida How Sweet It Is Waste Hungry Like the Wolf What's Going On? Count on Me When Love Comes To Town Dancing in the Moonlight Workin’ My Way Back To You Every Breath You Take You’re All I Need . Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic You’ve Got a Friend Everything Fire and Rain CONTEMPORARY BALLADS Get Lucky A Simple Song Hey, Soul Sister After All How Sweet It Is All I Do Human Nature All My Life I Believe All In Love Is Fair I Can’t Help It All The Man I Need I Can't Help Myself Always & Forever I Feel Good Amazed I Was Made To Love Her And I Love Her I Saw Her Standing There Baby, Come To Me I Wish Back To One If I Ain’t Got You Beautiful In My Eyes If You Really Love Me Beauty And The Beast I’ll Be Around Because You Love Me I’ll Take You There Betcha By Golly -

BROKEN HORN BULL a Collection of Essays

BROKEN HORN BULL A Collection of Essays by MARTIN ANBEGWON ATUIRE B.A., University of Colorado, Denver, l998 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Fine Arts Department of English 2011 This thesis entitled: Broken Horn Bull A Collection of Essays written by Martin Anbegwon Atuire has been approved for the Department of English Associate Professor Marcia Douglas Associate Professor John-Michael Rivera _________________________________________ Assistant Professor Noah Eli Gordon Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Abstract Atuire, Martin Anbegwon (M.F.A. English, Creative Writing) Broken Horn Bull A Collection of Essays Thesis directed by Associate Professor Marcia Douglas I am a native Buli speaker and belong to the second generation of Bulsa who had the chance to obtain formal education in English. None of my grandparents, and hardly anyone from their generation had the opportunity to go to school. The first schools were established by the British beginning with my father’s generation. My mother never had the opportunity to go to school. She was therefore non-literate in English and Buli. During the colonial era, schools were mostly in the southern part of Ghana while the north, where I come from, was mostly left alone to its native ways and native forms of education. With such background I find myself as a writer working at a very interesting and exciting time in the history of our language and narrative forms. -

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 10/13/2010 12:42 Pm

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 10/13/2010 12:42 pm WNCU 90.7 FM Format: Jazz North Carolina Central University (Raleigh - Durham, NC) This Period (TP) = 10/06/2010 to 10/12/2010 Last Period (TP) = 09/29/2010 to 10/05/2010 TP LP Artist Album Label Album TP LP +/- Rank Rank Year Plays Plays 1 24 Tom Rizzo Imaginary Numbers Origin 2010 11 4 7 2 1 The Marsalis Family Music Redeems Marsalis 2010 10 12 -2 2 288 The Clayton Brothers The New Song And Dance ArtistShare 2010 10 0 10 4 4 Freddy Cole Freddy Cole Sings Mr.B HighNote 2010 8 8 0 4 4 Conrad Herwig The Latin Side Of Herbie Half Note 2010 8 8 0 Hancock 4 10 Jim Rotondi 1000 Rainbows Posi-Tone 2010 8 7 1 4 10 James Moody Moody 4B IPO 2010 8 7 1 4 24 Mauricio De Souza Here. There... Pulsa 2010 8 4 4 4 288 Bobby Watson The Gates BBQ Suite Lafiya 2010 8 0 8 10 3 Tomas Janzon Experiences Changes 2010 7 9 -2 10 13 Stephen Anderson Nation Degeneration Summit 2010 7 6 1 10 24 Steve Turre Delicious & Delightful HighNote 2010 7 4 3 10 288 Mary Stallings Dream HighNote 2010 7 0 7 14 4 Larry Coryell Prime Picks HighNote 2010 6 8 -2 14 30 Chicago Afro Latin Jazz Blueprints Chicago Sessions 2010 6 3 3 Ensemble 16 4 Nobuki Takamen Live: At The Iridium Summit 2010 5 8 -3 16 13 Royce Campbell Trio What Is This Thing Called? Philology 2010 5 6 -1 16 13 Regina Carter Reverse Thread E1 2010 5 6 -1 16 17 Chris Massey Vibrainium Self-Released 2010 5 5 0 20 2 Kenny Burrell Be Yourself HighNote 2010 4 11 -7 20 4 Danilo Perez Providencia Mack Avenue 2010 4 8 -4 20 4 Curtis -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

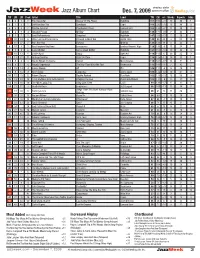

Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Dec

airplay data JazzWeek Jazz Album Chart Dec. 7, 2009 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW +/- Weeks Reports Adds 1 4 1 1 Eric Alexander Revival Of The Fittest HighNote 167 190 -23 10 46 1 2 1 3 1 Jeff Hamilton Trio Symbiosis Capri 166 236 -70 10 40 0 3 3 4 2 Poncho Sanchez Psychedelic Blues Concord Jazz 163 195 -32 11 40 0 4 6 7 4 Houston Person Mellow HighNote 149 171 -22 7 42 1 5 2 2 1 Joey DeFrancesco Snapshot HighNote 147 220 -73 7 50 2 6 23 39 6 Oliver Jones & Hank Jones Pleased To Meet You Justin Time 144 99 45 4 52 10 7 16 27 7 Roni Ben-Hur Fortuna Motema 136 120 16 4 42 2 8 10 4 1 Roy Hargrove Big Band Emergence EmArcy/Groovin’ High 128 136 -8 15 34 1 9 7 8 6 Cedar Walton Voices Deep Within HighNote 121 153 -32 10 44 0 10 18 12 1 Jackie Ryan Doozy Open Art 119 113 6 20 35 0 11 13 21 11 Graham Dechter Right On Time Capri 116 128 -12 10 33 1 12 5 6 3 Gerald Wilson Orchestra Detroit Mack Avenue 114 181 -67 13 41 1 13 8 11 8 Angela Hagenbach The Way They Make Me Feel Resonance 113 148 -35 7 42 2 14 19 14 4 James Moody 4A IPO 105 111 -6 14 34 1 15 9 15 9 Steve Davis Eloquence Jazz Legacy 104 146 -42 10 41 0 16 15 29 5 Robert Glasper Double Booked Blue Note 103 123 -20 15 56 0 16 19 32 16 Terell Stafford, Dick Oatts Quintet Bridging The Gap Planet Arts/Blujazz 103 111 -8 5 27 0 18 10 10 10 The Mike Longo Trio Sting Like A Bee C.A.P. -

Healing Relationships

HEALING RELATIONSHIPS This book is dedicated to the loving memory of my Mother, Oma Moseley, who taught me the power of words & my Daddy, Fred Moseley, who taught me how to play with words HEALING RELATIONSHIPS A Preaching Model DAN MOSELEY Copyright ©2009 by Dan Moseley. All rights reserved. For permission to reuse content, please contact Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, www.copyright.com. Bible quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Those quotations marked RSV are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1952, [2nd edition, 1971] by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover image: FotoSearch Cover and interior design: Elizabeth Wright Visit Chalice Press on the World Wide Web at www.chalicepress.com 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moseley, Dan. Healing relationships : a preaching model / by Dan Moseley. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-8272-1455-2 1. Preaching. 2. Interpersonal relations--Religious aspects—Christianity—Sermons. 3. Sermons, American. I. Title. BV4222.M67 2008 251—dc22 2008026811 Printed in United States of America Contents Prelude vii 1. The Reluctant Pilgrim Sermon 1 Leaving Home (Ex. 3:1–12) 2.