INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 10/13/2010 12:42 Pm

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 10/13/2010 12:42 pm WNCU 90.7 FM Format: Jazz North Carolina Central University (Raleigh - Durham, NC) This Period (TP) = 10/06/2010 to 10/12/2010 Last Period (TP) = 09/29/2010 to 10/05/2010 TP LP Artist Album Label Album TP LP +/- Rank Rank Year Plays Plays 1 24 Tom Rizzo Imaginary Numbers Origin 2010 11 4 7 2 1 The Marsalis Family Music Redeems Marsalis 2010 10 12 -2 2 288 The Clayton Brothers The New Song And Dance ArtistShare 2010 10 0 10 4 4 Freddy Cole Freddy Cole Sings Mr.B HighNote 2010 8 8 0 4 4 Conrad Herwig The Latin Side Of Herbie Half Note 2010 8 8 0 Hancock 4 10 Jim Rotondi 1000 Rainbows Posi-Tone 2010 8 7 1 4 10 James Moody Moody 4B IPO 2010 8 7 1 4 24 Mauricio De Souza Here. There... Pulsa 2010 8 4 4 4 288 Bobby Watson The Gates BBQ Suite Lafiya 2010 8 0 8 10 3 Tomas Janzon Experiences Changes 2010 7 9 -2 10 13 Stephen Anderson Nation Degeneration Summit 2010 7 6 1 10 24 Steve Turre Delicious & Delightful HighNote 2010 7 4 3 10 288 Mary Stallings Dream HighNote 2010 7 0 7 14 4 Larry Coryell Prime Picks HighNote 2010 6 8 -2 14 30 Chicago Afro Latin Jazz Blueprints Chicago Sessions 2010 6 3 3 Ensemble 16 4 Nobuki Takamen Live: At The Iridium Summit 2010 5 8 -3 16 13 Royce Campbell Trio What Is This Thing Called? Philology 2010 5 6 -1 16 13 Regina Carter Reverse Thread E1 2010 5 6 -1 16 17 Chris Massey Vibrainium Self-Released 2010 5 5 0 20 2 Kenny Burrell Be Yourself HighNote 2010 4 11 -7 20 4 Danilo Perez Providencia Mack Avenue 2010 4 8 -4 20 4 Curtis -

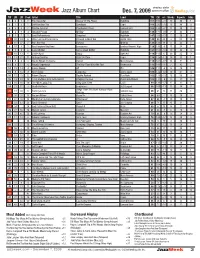

Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Dec

airplay data JazzWeek Jazz Album Chart Dec. 7, 2009 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW +/- Weeks Reports Adds 1 4 1 1 Eric Alexander Revival Of The Fittest HighNote 167 190 -23 10 46 1 2 1 3 1 Jeff Hamilton Trio Symbiosis Capri 166 236 -70 10 40 0 3 3 4 2 Poncho Sanchez Psychedelic Blues Concord Jazz 163 195 -32 11 40 0 4 6 7 4 Houston Person Mellow HighNote 149 171 -22 7 42 1 5 2 2 1 Joey DeFrancesco Snapshot HighNote 147 220 -73 7 50 2 6 23 39 6 Oliver Jones & Hank Jones Pleased To Meet You Justin Time 144 99 45 4 52 10 7 16 27 7 Roni Ben-Hur Fortuna Motema 136 120 16 4 42 2 8 10 4 1 Roy Hargrove Big Band Emergence EmArcy/Groovin’ High 128 136 -8 15 34 1 9 7 8 6 Cedar Walton Voices Deep Within HighNote 121 153 -32 10 44 0 10 18 12 1 Jackie Ryan Doozy Open Art 119 113 6 20 35 0 11 13 21 11 Graham Dechter Right On Time Capri 116 128 -12 10 33 1 12 5 6 3 Gerald Wilson Orchestra Detroit Mack Avenue 114 181 -67 13 41 1 13 8 11 8 Angela Hagenbach The Way They Make Me Feel Resonance 113 148 -35 7 42 2 14 19 14 4 James Moody 4A IPO 105 111 -6 14 34 1 15 9 15 9 Steve Davis Eloquence Jazz Legacy 104 146 -42 10 41 0 16 15 29 5 Robert Glasper Double Booked Blue Note 103 123 -20 15 56 0 16 19 32 16 Terell Stafford, Dick Oatts Quintet Bridging The Gap Planet Arts/Blujazz 103 111 -8 5 27 0 18 10 10 10 The Mike Longo Trio Sting Like A Bee C.A.P. -

Healing Relationships

HEALING RELATIONSHIPS This book is dedicated to the loving memory of my Mother, Oma Moseley, who taught me the power of words & my Daddy, Fred Moseley, who taught me how to play with words HEALING RELATIONSHIPS A Preaching Model DAN MOSELEY Copyright ©2009 by Dan Moseley. All rights reserved. For permission to reuse content, please contact Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, www.copyright.com. Bible quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Those quotations marked RSV are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1952, [2nd edition, 1971] by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover image: FotoSearch Cover and interior design: Elizabeth Wright Visit Chalice Press on the World Wide Web at www.chalicepress.com 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moseley, Dan. Healing relationships : a preaching model / by Dan Moseley. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-8272-1455-2 1. Preaching. 2. Interpersonal relations--Religious aspects—Christianity—Sermons. 3. Sermons, American. I. Title. BV4222.M67 2008 251—dc22 2008026811 Printed in United States of America Contents Prelude vii 1. The Reluctant Pilgrim Sermon 1 Leaving Home (Ex. 3:1–12) 2. -

Cultural & Heritagetourism

Cultural & HeritageTourism a Handbook for Community Champions A publication of: The Federal-Provincial-Territorial Ministers’ Table on Culture and Heritage (FPT) Table of Contents The views presented here reflect the Acknowledgements 2 Section B – Planning for Cultural/Heritage Tourism 32 opinions of the authors, and do not How to Use this Handbook 3 5. Plan for a Community-Based Cultural/Heritage Tourism Destination ������������������������������������������������ 32 necessarily represent the official posi- 5�1 Understand the Planning Process ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 32 tion of the Provinces and Territories Developed for Community “Champions” ��������������������������������������� 3 which supported the project: Handbook Organization ����������������������������������������������������� 3 5�2 Get Ready for Visitors ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 33 Showcase Studies ���������������������������������������������������������� 4 Alberta Showcase: Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump and the Fort Museum of the NWMP Develop Aboriginal Partnerships ��� 34 Learn More… �������������������������������������������������������������� 4 5�3 Assess Your Potential (Baseline Surveys and Inventory) ������������������������������������������������������������� 37 6. Prepare Your People �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 41 Section A – Why Cultural/Heritage Tourism is Important 5 6�1 Welcome -

Æ‚‰É”·ȯLj¾é “ Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ

æ‚‰é” Â·è¯ çˆ¾é “ 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & æ—¶é— ´è¡¨) Spectrum https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spectrum-7575264/songs The Electric Boogaloo Song https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-electric-boogaloo-song-7731707/songs Soundscapes https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/soundscapes-19896095/songs Breakthrough! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/breakthrough%21-4959667/songs Beyond Mobius https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/beyond-mobius-19873379/songs The Pentagon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-pentagon-17061976/songs Composer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/composer-19879540/songs Roots https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/roots-19895558/songs Cedar! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/cedar%21-5056554/songs The Bouncer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-bouncer-19873760/songs Animation https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/animation-19872363/songs Duo https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/duo-30603418/songs The Maestro https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-maestro-19894142/songs Voices Deep Within https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/voices-deep-within-19898170/songs Midnight Waltz https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/midnight-waltz-19894330/songs One Flight Down https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/one-flight-down-20813825/songs Manhattan Afternoon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/manhattan-afternoon-19894199/songs Soul Cycle https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/soul-cycle-7564199/songs -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

Austro-American Reflections: Making the Writings of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible To

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2012-12-12 Austro-American Reflections: Making the ritingsW of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible to English-Speaking Audiences Stephen Andrew Simon Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the German Language and Literature Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Simon, Stephen Andrew, "Austro-American Reflections: Making the ritingsW of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible to English-Speaking Audiences" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 3543. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3543 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Austro-American Reflections: Making the Writings of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible to English-Speaking Audiences Stephen A. Simon A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Robert McFarland, Chair Michelle James Cindy Brewer Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages Brigham Young University December 2012 Copyright © 2012 Stephen A. Simon All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Austro-American Reflections: Making the Writings of Ann Tizia Leitich Accessible to English-Speaking Audiences Stephen A. Simon Department of German Studies and Slavic Languages, BYU Master of Arts Ann Tizia Leitich wrote about America to a Viennese audience as a foreign correspondent with the unique and personal perspective of an immigrant to the United States. Leitich differentiates herself from other Europeans who reported on America in her day by telling of the life of the average working American. -

A Retrospective Journal for the Theater in England Trip

SUBWAYS AND SUBTEXTS: CONNECTING TRAINS OF THOUGHT FOR THE THEATER IN ENGLAND TRIP of December 27, 2004-January 9, 2005 By Kevin Cryderman In this theatre journal, rather than doing a play-by-play analysis at the time on the trip, I retrospectively move across plays in my discussion of various themes and topics that I saw as points of connection. Therefore, most of the twenty-one productions I saw appear within multiple sections to allow for various links during my casual conversations with myself. As with most journals, these are fragmentary, inelegant and ineloquent reflections rather than fully-worked-out argumentative essays. Nevertheless, I do bring in quotations from the playscripts or background information in relation to both the topics of my critical responses to the plays and my experiences in London, namely: storytelling; intersecting space-time; the narrativization of history; race, nation, roots, gender, sexuality and their representation; cinematic techniques and projection; adaptation and re- writing; re-staging Shakespeare; language and audience interpellation; music and dance; and props and lighting. As I begin writing this journal on my computer, I am drinking tea and dipping a madeleine in it (Truth be told, it’s a gingerbread cookie with M&Ms on top, and this introduction was written after the journal.) as I think about the question of roots and heritage—a topic suggested by both my trip and some of the plays. Along with Germany and the Ukraine, part of my own heritage and familial roots lie in Ireland and Britain. The French and the English founded my own home country of Canada, officially at least, so I suppose this trip is a return to The Mother Land. -

Tourisme Outaouais

OFFICIAL TOURIST GUIDE 2018-2019 Outaouais LES CHEMINS D’EAU THE OUTAOUAIS’ TOURIST ROUTE Follow the canoeist on the blue signs! You will learn the history of the Great River and the founding people who adopted it. Reach the heart of the Outaouais with its Chemins d’eau. Mansfield-et-Pontefract > Mont-Tremblant La Pêche (Wakefield) Montebello Montréal > Gatineau Ottawa > cheminsdeau.ca contents 24 6 Travel Tools regional overview 155 Map 8 Can't-miss Experiences 18 Profile of the Region 58 top things to do 42 Regional Events 48 Culture & Heritage 64 Nature & Outdoor Activities 88 Winter Fun 96 Hunting & Fishing 101 Additional Activities 97 112 Regional Flavours accommodation and places to eat 121 Places to Eat 131 Accommodation 139 useful informations 146 General Information 148 Travelling in Quebec 150 Index 153 Legend of Symbols regional overview 155 Map TRAVEL TOOLS 8 Can't-miss Experiences 18 Profile of the Region Bring the Outaouais with you! 20 Gatineau 21 Ottawa 22 Petite-Nation La Lièvre 26 Vallée-de-la-Gatineau 30 Pontiac 34 Collines-de-l’Outaouais Visit our website suggestions for tours organized by theme and activity, and also discover our blog and other social media. 11 Website: outaouaistourism.com This guide and the enclosed pamphlets can also be downloaded in PDF from our website. Hard copies of the various brochures are also available in accredited tourism Welcome Centres in the Outaouais region (see p. 146). 14 16 Share your memories Get live updates @outaouaistourism from Outaouais! using our hashtag #OutaouaisFun @outaouais -

Cultural & Heritage Tourism: a Handbook for Community Champions

Cultural & HeritageTourism a Handbook for Community Champions Table of Contents The views presented here reflect the Acknowledgements 2 opinions of the authors, and do not How to Use this Handbook 3 necessarily represent the official posi- tion of the Provinces and Territories Developed for Community “Champions” ��������������������������������������� 3 which supported the project: Handbook Organization ����������������������������������������������������� 3 Showcase Studies ���������������������������������������������������������� 4 Learn More… �������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Section A – Why Cultural/Heritage Tourism is Important 5 1. Cultural/Heritage Tourism and Your Community ��������������������������� 5 1�1 Treasuring Our Past, Looking To the Future �������������������������������� 5 1�2 Considering the Fit for Your Community ���������������������������������� 6 2. Defining Cultural/Heritage Tourism ��������������������������������������� 7 2�1 The Birth of a New Economy �������������������������������������������� 7 2�2 Defining our Sectors ��������������������������������������������������� 7 2�3 What Can Your Community Offer? �������������������������������������� 10 Yukon Showcase: The Yukon Gold Explorer’s Passport ����������������������� 12 2�4 Benefits: Community Health and Wellness ������������������������������� 14 3. Cultural/Heritage Tourism Visitors: Who Are They? ������������������������ 16 3�1 Canadian Boomers Hit 65 ���������������������������������������������� 16 3�2 Culture as a -

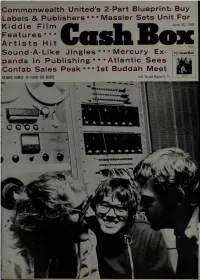

Commonwealth United's 2-Part Blueprint

' Commonwealth United’s 2-Part Blueprint: Buy Labels & Publishers ••• Massler Sets Unit For June 22 1968 Kiddie Film ™ ' Features * * * Artists Hit • * * Sound-A-Like Jingl Mercury Ex- iff CashBox pands In Publishing • • Atlantic Sees Confab Sales Peak** 1st Buddah Meet Equals ‘ Begins Pg. 51 RICHARD HARRIS: HE FOUND THE RECIPE Int’l. Section Take a great lyric with a strong beat. Add a voice and style with magic in it. Play it to the saturation level on good music stations Then if it’s really got it, the Top-40 play starts and it starts climbingthe singles charts and selling like a hit. And that’s exactly what Andy’s got with his new single.. «, HONEY Sweet Memories4-44527 ANDY WILLIAMS INCLUDING: THEME FROM "VALLEY OF ^ THE DOLLS" ^ BYTHETIME [A I GETTO PHOENIX ! SCARBOROUGH FAIR LOVE IS BLUE UP UPAND AWAY t THE IMPOSSIBLE * DREAM if His new album has all that Williams magic too. Andy Williams on COLUMBIA RECORDS® *Also available fn A-LikKafia 8-track stereo tape cartridges : VOL. XXIX—Number 47/June 22, 1968 Publication Office / 1780 Broadway, New York, New York 10019 / Telephone: JUdson 6-2640 / Cable Address: Cash Box. N. Y. GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Vice President LEON SCHUSTER Treasurer IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL TOM McENTEE Assoc. Editor DANIEL BOTTSTEIN JOHN KLEIN MARV GOODMAN EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS MIKE MARTUCCI When Tragedy Cries (hit ANTHONY LANZETTA ADVERTISING BERNIE BLAKE Director of Advertising ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES STAN SOIFER New York For 'Affirmative'Musif BILL STUPER New York HARVEY GELLER Hollywood WOODY HARDING Art Director COIN MACHINES & VENDING ED ADLUM General Manager BEN JONES Asst. -

20210824 Recensieoverzichtplaten69tmheden

ARTIEST PLAAT LABEL RECENSENT NR. 1000+1 Butterfly Garden El Negocito Fluitman 224 3 Brave Souls 3 Brave Souls Challenge Korten 191 3/4 Peace 3/4 Peace El Negocito Loo, te 207 3/4 Peace Rainy Days On The Common Land El Negocito Loo, te 250 37 Fern 37 Fern TryTone Loo, te 348 3Hands Clapping Shaman Dance Juice Junk Records Korten 99 3times7 Squeeze The Lemon Eigen Beheer Hollebrandse 281 4Beat6 Plays The Music Of Benny Goodman Vol. 1 Eigen Beheer Lammen 85 4tet Different Song Leo Records Loo, te 178 5 Up High 5 Up High Timeless Fluitman 273 6 Spoons, 1 Kitchen Blend LopLop Beetz 201 6ix Almost Even Further Leo Records Loo, te 187 A A.G.N.Z. (Azzolina, Govoni, Nussbaum & Zinno) Chance Meeting Whaling City Sound Fluitman 264 Aagre, Froy Cycle Of Silence ACT Fluitman 133 Aardvark Jazz Orchestra American Agonistes Leo Records Loo, te 100 Aardvark Jazz Orchestra Evocations Leo Records Loo, te 181 Aardvark Jazz Orchestra Impressions Leo Records Loo, te 226 Abate, Greg Magic Dance Whaling City Sound Valk, de 353 Abate, Greg & Phil Woods Kindred Spirits Live At Chan's Whaling City Sound Fluitman 257 Abate, Greg & Tim Ray Trio Road To Forever Whaling City Sound Fluitman 274 Abdelnour/Schild La Louve Wide Ear Loo, te 322 Abercrombie Quartet, John Wait Till You See Her ECM Korten 128 Abercrombie Quartet, John Within A Song ECM Korten 183 Abercrombie Quartet, John 39 Steps ECM Beetz 209 Abercrombie, John The Third Quartet ECM Korten 76 Abercrombie, John & John Ruocco Topics Challenge Fluitman 90 Ablanedo, Pablo ReContraDoble Creative Nation Music Fluitman 197 Abou-Khalil, Rabih Em Português Enja Loo, te 101 Abou-Khalil, Rabih Selection Enja Loo, te 131 Abou-Khalil, Rabih Trouble In Jerusalem Enja Loo, te 150 Abrams, Jess Growing Up Challenge Huser 93 Abrams, Muhal Richard Sound Dance Pi Recordings Loo, te 161 Absolute Ensemble (ft.